On 9 May 1997, the Philippine Navy's dilapidated tank landing ship BRP Sierra Madre (LT-57) ran aground on a reef near the Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratly Islands. She was stranded, and it was certain the ship could not be removed under her own power.

Six days later, two Chinese frigates reportedly steamed into the area and trained their guns on the stranded hulk. It was alleged that no assistance was offered by the Chinese ships. But supposing they had, their help would not have been desired or welcomed by the crew of the old tank landing ship. The Sierra Madre had been run aground intentionally to serve as an outpost to boost the Philippines' claim to sovereignty over the Spratly islands. It was one of a long-running series of actions on many sides over claims to the hotly contested South China Sea.

Though her hull is today pockmarked with gaping holes, and she is for all intents and purposes no longer seaworthy, the Sierra Madre remains in commission and is thus an official extension of Philippine sovereign territory. The rusting and battered hulk still houses a contingent of Philippine Marines staking claim to the area.

The old LST is named after the Sierra Madre Mountains in the northern part of the Philippines, which are home to some of the country's most remote and inaccessible communities. It is only fitting, then, that the ship should have become a remote and inaccessible outpost herself.

While extensive media coverage has focused on the rusting World War II–era landing ship in her current role as an international flashpoint, much less time has been spent discussing just how the Sierra Madre came to be in the Philippines at all. In fact, the old LST had a long and decorated career spanning three navies and multiple continents over five decades.

The Sierra Madre began her long career as USS LST-821. The tank landing ship was laid down by the Missouri Valley Bridge & Iron Works in Evansville, Indiana, on 19 September 1944, one of more than a thousand LSTs that would be built for service in World War II. A little less than a month later, she was launched for her cruise down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where she was officially commissioned on 22 November, with Lieutenant C. J. Rudine in command. She sailed for the Pacific theater, spending most of her time ferrying supplies between Eniwetok, Okinawa, Ie Shima, Ulithi, Guam and other bases in preparation for the expected invasion of Japan. The ship saw little action in the war, though she did earn one battle star. With the dropping of the atomic bombs in August 1945 and Japan's subsequent surrender, LST-821 instead focused on supporting the occupation that country. She sailed for the United States on 11 December 1945 and was decommissioned and placed in reserve on 8 July 1946.

While she sat in reserve, LST-821 and all of the other LSTs not assigned to the Maritime Sea Transportation Service or the Shipping and Control Administration in Japan were renamed after U.S. counties and parishes. LST-821 became the USS Harnett County. Within a decade she would be called to again serve her country.

After the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the escalation of the Vietnam War, it became clear that the LSTs would be very useful ships. All of the reserve LSTs were reactivated for service, and four—the Garrett County, Hunterdon County, Jennings County, and Harnett County—were refitted as floating bases for the Mekong Delta Mobile Afloat Force (later the Mobile Riverine Force) in Operation Game Warden.

The four LSTs were heavily modified, receiving:

A day and night landing area for UH-1B Seawolf helicopter gunships

Refueling and rearming facilities for those gunships

Four new boat booms for mooring up to 16 PBRs alongside the ship

A large cargo boom to lift PBRs out of the water for repairs on board ship

Shops for engine, pump, and hull repairs on PBRs

Improved fresh water distillation facilities for an increase in complement

Upgraded radio, navigation, and electronic equipment

Each LST would provide 24-hour-a-day support for a fleet of 10 PBRs and a fire-support team of 2 helicopter gunships—Army UH-1Bs transferred to the Navy as Seawolves—in addition to close fire support provided by 40-mm guns mounted on board ship.

Life on board the Harnett County was cramped, to say the least. With a complement of 119 and accommodations for 266, the LST had to fit a lot of men and workspaces within her 328-foot length. The second Game Warden support ship to arrive in country, she took station off Dong Tam on 17 January 1967.

The crew of the Harnett County served with notable distinction during their two years in Game Warden and on through to 1970. Her crew was awarded with two Presidential Unit Citations for "extraordinary heroism" and for performance that was "superb in every phase of her diverse actions." One Army captain recalled that the close fire support provided by the Harnett County "saved my life . . . and the lives of the Vietnamese troops I was advising." Additionally, the men of the Harnett County earned nine battle stars and three Navy Unit Commendations for their service in Vietnam.

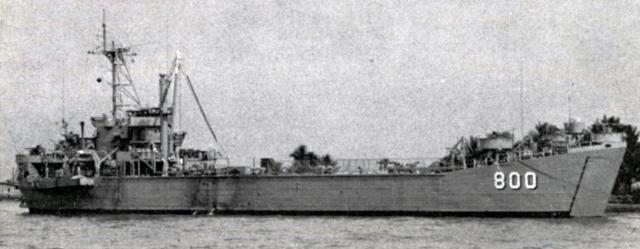

Late in 1969, much of the Mobile Riverine Force and its ships was transferred to the Republic of South Vietnam. The LSTs would not be far behind. Redesignated as a Patrol Craft Tender (AGP), the Harnett County (AGP-821) was formally transferred to South Vietnam under provisions of the Military Assistance Program on 12 October 1970, becoming the RVNS My Tho (HQ-800). It was in this role that she would save literally thousands of lives.

The My Tho served the South Vietnamese Navy in the riverine war though early 1975. Late that April, it became all too clear that Saigon and the government of South Vietnam would soon capitulate and many Vietnamese personnel and civilians were in terrible danger as a result.

As Saigon began to fall, the My Tho, her decks, holds, and every other space crammed with an estimated 3,000 refugees, set out downriver to the sea one last time; she would never return to Vietnam. The vessel joined an armada of 31 other South Vietnamese Navy ships that rendezvoused with the USS Kirk (DE-1087) in a desperate bid to rescue what was left of the navy and the roughly 30,000 to 40,000 people its ships were carrying.

This "E-Plan," developed by Defense Department Attache Richard Armitage and Captain Kiem Do, Deputy Chief of Operations of the South Vietnamese Navy, was a matter of extreme urgency. Captain Paul Jacobs of the Kirk later recalled the gravity of the situation when he received his orders to rendezvous with the flotilla from Admiral Donald Whitmire, commander of Operation Frequent Wind. "We're going to have to send you back to rescue the Vietnamese navy," Captain Jacobs remembered being told. "'We forgot 'em. And if we don't get them or any part of them, they're all probably going to be killed.'" The flotilla met at Con Son Island off Vietnam's southern coast and headed for Subic Bay in the Philippines in a desperate bid for safety.

So desperate was the situation on board the My Tho that a helicopter from the LST took off from the ship and landed aboard the Kirk to seek urgently needed food and medical supplies. The helicopter crew had failed to notice their fuel tank had been riddled with bullet holes, and that they had only a mere five minutes of flying time as a result. But they had made it to the Kirk and returned with the lifesaving supplies. The My Tho and her precious human cargo made the journey across the South China Sea largely in one piece.

But there was a huge catch in the plan. The Philippine government by that time had recognized the North Vietnam's communist government as the lawful government for all of Vietnam, and it, of course, demanded the return of the ships. U.S. Ambassador to the Philippines William Sullivan, as recounted in Jan K. Herman's The Lucky Few: The Fall of Saigon and the Rescue Mission of the USS Kirk, made clever use of a provision of the Military Assistance Program that stated if the receiving nation no longer had use of the donated equipment, it would be returned to U.S. custody.

Brokering a gentleman's agreement with the Philippine government, the My Tho and the other South Vietnamese Navy vessels would be permitted to dock at Subic Bay and discharge the thousands of refugees on board them.They would first have to be re-flagged as U.S. Navy ships under U.S. custody, with the nod that those ships would later be transferred to the Philippine Navy.

The My Tho, accordingly, entered Subic Bay as a U.S. ship after her South Vietnamese flag was lowered in a solemn ceremony at sea one last time. Those on board disembarked to begin their new lives. More than 131,000 refugees from Vietnam and elsewhere would be settled in the United States over the next several years as part of the larger Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act.

The ship sat moored in Subic Bay until April 1976, when she was officially transferred over to the Philippines. The LST was bought outright that October, becoming the BRP Dumagat (AL-57) and later the Sierra Madre (LT-57). She served as an amphibious transport through the early 1990s until her most recent incarnation as a stationary outpost.