In May 1905, the Russian Baltic Fleet’s 29 warships and their auxiliaries steamed northwestward through the Yellow Sea towards Vladivostok. They had endured a grueling seven-month journey that would soon end in the waters between Korea and Japan, near the island of Tsushima. The Russians’ mission was to relieve the beleaguered Far East Fleet in northeast Asia, where Imperial Japanese forces had executed a stunning surprise attack and then bottled up, decimated, and taken the surrender of the bulk of Russian naval forces in Asia.

More than a century later, the fateful Russian voyage still carries a multitude of lessons. Tactical mistakes, logistical fragility, and geopolitical failings doomed the Russians to defeat a hemisphere away from home and ushered in a new century characterized by world wars and catastrophe. As America confronts the possibility of naval war in East Asia, the U.S. Navy should examine Russia’s drift towards Tsushima and ponder whether it is on course for a 21st-century redux of the Russian Navy’s doom.

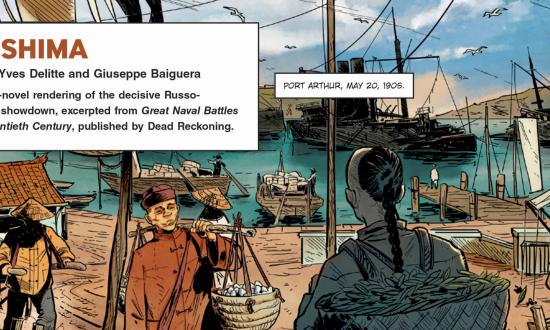

A Red Sun Rises

The war had been anything but easy for the Russians. An abortive attempt by the First Pacific Squadron in August 1904 to sortie from Port Arthur (in modern Dalian, China), break the Japanese blockade, and join with a smaller force in Vladivostok resulted in the battle of the Yellow Sea. The tactical stalemate was a strategic victory for Japan—some of the Russian squadron scattered, but most of the fleet returned to Port Arthur, around which the Imperial Japanese Army’s noose continually tightened.

Fierce land battles on the Liaotung Peninsula (on the tip of which lay Port Arthur) slowly cut off the port’s connection to Siberia, while the Japanese Army marched into Manchuria to hold off potential Russian reinforcements. Japan’s blockade and land-based fires excised Russia’s Far East naval power, stunning Western observers, who saw upstart Japan as a growing but still distant rival.

With disaster unfolding on the far side of the Eurasian landmass, Russian leadership faced a grim choice: allow the Far East Fleet to confront its fate alone, with the tide of the war slowly, incredibly, flowing in Japan’s favor, or mount a relief expedition. The only force Russia could send was on the wrong continent, and in an effort to turn the war around, the Russian Baltic Fleet sailed from Europe in October 1904.

The Japanese fully expected the Baltic Fleet to sail for Asia. Russian reinforcements were a ticking time bomb, lending a sense of urgency to Japanese operations. The Japanese Navy’s mission was twofold: “to destroy the Russian Pacific Fleet and secure the seas around Japan . . . [and] to support the landings of Army forces” in Korea and Manchuria.1

Russia planned to send reinforcements from Europe as early as July 1904, but the expedition faced innumerable delays in training, equipping, and supplying the fleet. The Japanese, meanwhile, wasted no time clearing Asia’s seas of Russian vessels.2

Japan’s strategy was quickly validated, and by December 1904, the Japanese had destroyed much of the Far East Fleet while it sat pierside or at anchor in Port Arthur. Having captured the heights surrounding the port, Japanese artillery sank four battleships and two cruisers and heavily damaged one more battleship. Japan had eliminated Russian naval power in the Far East while the Russian Baltic Fleet was still months away from its first, final, fateful battle.

Seven Months to Battle

The detachment from the Baltic Fleet, optimistically renamed the “Second Pacific Squadron” largely had to sustain itself with a fleet of colliers leased from a German company.3 Because of neutrality conventions, the Russians continually encountered nervous officials in European colonial ports who restricted access to fuel and supplies. European powers, perhaps sensing the tide of the war in the east, did not want to take a chance supporting Russia for the sake of future amity with the new Japanese powerhouse.4 The result had been a brutal voyage for the Russian fleet.

The deployment started with disaster. Sailing through the Dogger Bank in the North Sea off the coast of Europe, Russian lookouts somehow mistook British fishing vessels for Japanese torpedo boats and opened fire. The incident resulted in the sinking of an English trawler and the deaths of three civilians. The furious British—allies of Japan—mobilized the Royal Navy and threatened war. A British cruiser trailed the Russians until tensions had subsided.5

Furthermore, the Russian fleet was unable to use the Suez Canal because of a combination of their vessels’ draft (heavy loads of coal were required to sustain the squadron) and fears that the vengeful British might close the canal to the Russians.6 For the besieged First Pacific Squadron, the Baltic Fleet’s route around Africa was fatal; the Second Squadron’s voyage took seven months, more than twice as long as a voyage through Suez.7

By the time the Baltic Fleet arrived in Madagascar in December 1904, the Far East Fleet had been shattered. Notions of combining the two forces evaporated but the Baltic force continued onward. “For a time there seems to have been some suggestion that the great venture should be entirely abandoned. But . . . any such idea was quickly dismissed.”8

The Russian ships had been at sea for months, the crews were mutinous, the force they meant to augment was destroyed, and Port Arthur had been captured.9 “An opinion that the whole undertaking was doomed to failure . . . now began to find open expression” among the crew.10

Meanwhile, the Japanese, led by Admiral Togo Heihachiro, returned home after the victories at Port Arthur to refit and train. Togo, who had had to rely on untested crews equipped with cutting-edge technology, incorporated important lessons on tactics and more, learning from the clashes in the Yellow Sea.11 The Imperial Japanese Navy was rested, repaired, and spoiling for a fight, while their opponents arrived utterly exhausted.

Without enough coal aboard to take the longer route around Japan to Vladivostok, the Russians had to transit the Tsushima Strait to rendezvous with what was left of the Far East Fleet. Togo understood Russia’s logistical limitations and reached the same conclusion and deployed his screening force in the Strait. “Togo thus, by good scouting and choice of position, secured . . . his strategic object of bringing the Russian fleet to battle.”12 Battle between the fleets was “inevitable.”13

Hoist the Zulu Flag

At dawn on 27 May 1905, the cruiser Sinano Maru spotted the Russian hospital ship convoy and reported its position using a new technology: the wireless telegraph. With this intelligence in hand, Togo closed for battle.

Japanese scouts maintained a wary watch on the Russians, using the wireless to inform Togo of their every move, despite heavy fog. By early afternoon, the fleets found each other and the battle began in earnest. Togo hoisted a signal evocative of Nelson’s message at Trafalgar, but in efficient style. The four-color “Z” flag flew from the yardarm, its prearranged meaning:

“The fate of the Empire depends on today’s result, let every man do his utmost.”14

Japanese sailors would validate Togo’s encouragement. The newer, technologically advanced, quick-firing Japanese men-o-war pounded the beleaguered Russians, using superior speed to cross the Russian “T,” plunging raking fire down the Russian line. The battleships Oslyabya, Knyaz Suvorov, and Imperator Aleksandr III went to the bottom. The magazine on board the battleship Borodino, with 855 officers and men, took a direct hit from the cruiser Fuji. A single sailor survived. The Russians, looking with indescribable anxiety to the coming nightfall, fled southward to escape destruction

However, the next morning the Japanese regained sight of the tattered Russian fleet and continued their relentless pursuit. The Russians scrambled to hoist flags of surrender and the battle ended before lunch.

From the moment Togo’s force maneuvered ahead of the Russian battle line to cross their T, the outcome had been in little doubt. Naval scholar Julian Corbett said simply: “Tactical interest ended after the first few moves, and from . . . the rest of the day there is little professional profit to be gained.”15 A damning indictment of Russian ineffectiveness.

The butcher’s bill was dear: 21 Russian ships sunk, 7 more captured, 5,045 Russians dead. Togo lost a mere 117 sailors and three torpedo boats. The stunning victory forced Russia to the negotiating table and the war ended with a European power defeated, Japan victorious, and a dawning era of big gun battleships that would persist for nearly half a century.

The Ghosts of Tsushima

Corbett’s derision rings through the years; indeed, examining columns of battleships maneuvering within visual range will yield few auguries for modern naval war. However, the strategic environment around the doomed Russian voyage to Tsushima is a trove of potential pitfalls for any American naval campaign in the far Western Pacific. The effectiveness of shore-based fires against naval power, the reluctance of neutral (and allied) powers to enter the conflict, the operational realities imposed by global chokepoints, and the logistic requirements of transglobal war remain unchanged in the ensuing century.

Safe at Sea, at Risk at Anchor

Japan’s initial surprise attack on Port Arthur demonstrated the harbor’s vulnerability, and once the Imperial Japanese Army landed in Manchuria, the clock was ticking on Port Arthur as a refuge. While the Army tightened its grip ashore, the Navy mined the approaches to the port and waited for the inevitable Russian sortie. The result was the Far East Fleet’s gradual destruction by a combination of naval and land-based fires.

Modern U.S. forces ring the periphery of Chinese local waters from Japan to Singapore, and the prospect of Chinese forces invading U.S. bases at Yokosuka or Sasebo is incredibly remote. However, unlike Imperial Japan, who needed the hills above Port Arthur to bombard the Russians, Chinese long-range, land-based ballistic missiles on the Asian mainland can menace U.S. forces as far away as Singapore and Guam. Modern technology allows something Togo could only have dreamed about: threatening the enemy’s in-port fleet without ever leaving home.

The U.S. Seventh Fleet in the Western Pacific is at risk of shore-based bombardment from the outset of hostilities. Just as the Port Arthur squadron had to sortie to the open sea to survive, reaching the open ocean may be the only chance forward-deployed U.S. forces have to survive a salvo from mainland China.

No Friends, Only Interests

Any plan for U.S. ships to slip moorings in Japan and race for the deep blue sea may face another complication that plagued Russians on their voyage to Tsushima. European powers such as France, Spain, and Portugal had political reasons for denying or curtailing Russian access to foreign ports. The Dogger Bank incident, neutrality conventions, and the need to maintain cordial relationships with the new Japanese power (and each other) drove European powers to limit open support for the Russian relief force.

One of the most likely scenarios for war between the United States and China is a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. Such a conflict might draw in regional powers, but, as with the Russo-Japanese War, it may just as well drive even American allies to a tepid neutrality.

Would Thailand, South Korea, or the Philippines risk China’s wrath over Taiwan? Their cities and militaries lie in the footprint of China’s missile forces; would Japan (for argument’s sake) trade Tokyo for Taipei? A scenario in which Japan forbids the sortie of Seventh Fleet in exchange for China’s forbearance is easy to envision. Would the U.S. Navy then risk the nation’s relationship with Japan to set sail all the same? Given the flaws exposed in surface ship handling and readiness after 2017’s at-sea collisions, could U.S. forces successfully slip out of Tokyo Roads without aid and sail straight into war at all?

Only An Ocean Away

Like the Russian Far East Fleet, Seventh Fleet is already overmatched in East Asia.16 China’s entire Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy—360 warships—is based on the “near seas,” i.e., the bodies of water between the Asian mainland and the “first island chain.”17 Seventh Fleet has “at any given time . . . roughly 50–70 ships” under its command.18 Of course, in a crisis the United States would augment Seventh Fleet with the U.S.-based Third Fleet as much as possible, but at a certain point the United States will go to war with what it has in theater.

The Russians knew nearly a year before Tsushima that the Baltic Fleet would be needed in Asia. By July 1904, plans were finalized, but the fleet did not sail until October, and it did not arrive until May 1905. By then it was too late to save the Far East Fleet and Port Arthur.

An relief force from the United States would reach Asia much more quickly than the Russians did. However, despite the advantages of U.S. West Coast geography, any relief effort would take a discrete period to arrive in theater. Like the Russian Far East Fleet once was, during that period—days, weeks, or months—the Seventh Fleet would be on its own. U.S. forces from the Atlantic would face a voyage like the Russians’, and as the 2021 Suez Canal blockage by the Ever Given demonstrated, any number of complications might deny the easiest route to Asia for U.S. forces.19 The geography of East Asia yields certain unavoidable chokepoints and funnels for any relief force.

Learning on Home Turf

At the war’s outbreak, Imperial Japanese sailors had no combat experience. They operated new ships with unfamiliar technology and employed tactics that had not been validated in battle.20 Chinese vessels, which have slid down slipways in alarming numbers in recent years, are similarly crewed by green sailors without combat experience, using systems and tactics that have remained on war college drawing boards for decades.

Modern naval warfare—characterized by missile salvos, hypersonic weapons, and submarine-launched cruise missiles—is similarly conceptual: there has not been a major naval conflict since the Falklands War. This is true for both the U.S. and Chinese navies. Despite periodic Tomahawk strikes against terrorist or authoritarian targets over the past three decades, the U.S. Navy has not fired a missile in anger against an enemy naval vessel since 1988’s Operation Praying Mantis.

While the United States marshals its forces for a relief expedition on a global scale, the Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy will play on “home turf,” absorbing valuable lessons learned and preparing for the battle to come, just as Togo did in early 1905.

Talk Logistics

Logistics requirements hamstrung the Russian Navy. A lack of colonial coaling stations and reluctance by European powers to provide substantial support sent the Russians to the open market. The result was contracted supply vessels from Germany and more complications.

Although eventually the Second Pacific Squadron honed its ability to resupply at sea, initially the fleet crawled around Africa, stopping frequently to refuel. The voyage took its toll on the ships and crews, to the point of mutiny. The civilian mariners of the coaling freighters refused to sail closer to the conflict than Indochina. This lack of supply forced the Russians to take the route past Tsushima that Togo anticipated. Logistical fragility doomed the Russian fleet as much as Togo’s line of battle did.

American logistics are hardly in better shape. The U.S. Merchant Marine and sealift fleets are aging, non-mission capable, unprotected vessels. As of 2019, more than 20 percent of sealift and surge ships were not mission capable and the average age of the fleet was 44 years.21 In addition, Navy leadership has told civilian merchant mariners that they would be “on their own” in the event of a conflict.22 The Navy will be unable to protect them in an already imbalanced theater, how far west will the diminished U.S. Merchant Marine sail? To Japan and the heart of the conflict? To Guam under the threat of Chinese missiles? To Pearl Harbor? The hesitant mariners of the Amerika-Hamburg line went no closer than modern Vietnam, is the Navy prepared for similar hesitancy in an age of satellite reconnaissance and long-range missiles?

Divided Houses

Imperial Japan seized on political divisions in Russia, surreptitiously supporting revolutionary groups to divide the public on the issue of war with Japan.23 These efforts reached their apex in the mutiny. Japan also took advantage of Russia’s strategic difficulties. Wariness of Ottoman Turkey, Germany, and Austria meant that Russia had to balance war in the East against commitments in the West.24 Japan bided its time, waiting to strike Russia until an outcome favorable to Japan was likely.

This century-old scenario should look familiar to modern readers. China’s online efforts to divide the public are pernicious: downplaying the genocide against Uighurs in Xinjang province, mischaracterizing pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, positing that COVID-19 originated at Fort Detrick, Maryland, or rationalizing excessive China’s territorial claims.25 The Chinese Communit Party’s intent is the same as Imperial Japan’s: to sow doubt and misinformation.26

The strategic problem also rings down through the years. Those who see Putin’s Russia as a military threat equal to China protest calls for increased naval funding, while adversaries like Iran, North Korea, and terrorism vie for strategic attention. The lack of strategic clarity that plagued Russia in 1904 persists in the United States in 2021.

Tsushima serves as a stark reminder that future naval conflict in the West Pacific will not be easy. Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. Navy has suffered declines in seamanship, force size and composition, and logistics. Combine those “in-house” problems with geography, geopolitics, and looming budgetary fistfights in Washington, and the Navy may be drifting towards a modern-day Tsushima.

These are the lessons of Tsushima. Strategic understanding and the ability to move a navy across the world to arrive in fighting shape, supplied, armed, supported with materiel and political willpower are what will determine whether the United States Navy continues its drift towards Tsushima or whether, by aggressively addressing these issues, the United States might convince China that the peaceful resolution of disagreements in East Asia is preferable to the gamble of conflict.

1. Yoji Koda, “The Russo-Japanese War—Primary Causes of Japanese Success,” Naval War College Review 58, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 17.

2. R. M. Connaughton, Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear: Russia’s War with Japan, Kindle (London: New York, N.Y: Orion, 2020), 322.

3. Geoffrey Jukes, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, Osprey Guide to Modern Warfare (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2014), 67.

4. Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defense, Official History, Naval and Military, of the Russo-Japanese War (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1910), 735.

5. Connaughton, Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear, 337.

6. Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defense, Official History of the Russo-Japanese War, 28.

7. By contrast, Russian reinforcements (the Third Pacific Squadron) departed Europe in February, transited the Suez, and rendezvoused with the Second Squadron off Indochina in May, a mere three months.

8. Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defense, Official History of the Russo-Japanese War, 731.

9. A January 1905 mutiny on board the cruiser Nakhimov resulted in the execution of 14 sailors. Jukes, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, 69.

10. Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defense, Official History of the Russo-Japanese War, 733.

11. Vladimir Ivanovich Semenov, The Battle of Tsu-Shima: Between the Japanese and Russian Fleets, Fought on 27th May 1905, ed. George Sydenham Clarke, trans. Alexander Bertram Lindsay (London: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1910), xxiii.

12. Alfred T. Mahan, “Reflections, Historic and Other, Suggested by the Battle of the Sea of Japan,” U.s. Naval Institute Proceedings 32, no. 2 (April 1906).

13. Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defense, Official History of the Russo-Japanese War, 730.

14. Connaughton, Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear, 346.

15. Julian Corbett, “Official History of the Russo Japanese War,” in Connaughton, 364.

16. Geoff Ziezulewicz, “China’s Navy Has More Ships than the US. Does That Matter?,” Navy Times (blog), 9 April 2021.

17. The first island chain is a term coined by Chinese defense observers for the string of islands running southward from the Japanese home islands, through Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore.

18. Commander, U.S. Seventh Fleet, “Facts Sheet,”.

19. Julian Ryall, “Suez Accident: Japanese Shippers Look for New Ways to Europe,” Deutsche Welle, 19 may 21, sec. Asia.

20. Koda, “The Russo-Japanese War—Primary Causes of Japanese Success,” 24.

21. Salvatore R. Mercogliano, “Suppose There Was a War and the Merchant Marine Didn’t Come?,” U.S. Naval Institute, January 2020, .

22. David Larter, “‘You're on Your Own’: US Sealift Can’t Count on Navy Escorts in the next Big War,” Defense News, October 11, 2018, sec. Naval.

23. Koda, “The Russo-Japanese War—Primary Causes of Japanese Success,” 12.

24. Koda, 13.

25. Deirdre Shesgreen, “The US Says China Is Committing Genocide against the Uyghurs. Here’s Some of the Most Chilling Evidence.,” USA Today, April 2, 2021, sec. Politics. Krassi Twigg and Kerry Allen, “The Disinformation Tactics Used by China,” BBC News, March 12, 2021, sec. Reality Check.

26. Patrick Tucker, “The West Isn’t Ready for the Coming Wave of Chinese Misinformation: Report,” Defense One, March 7, 2019, sec. Science & Tech.