The Fighting Corsairs: The Men of Marine Fighting Squadron 215 in the Pacific During World War II

Jeff Dacus. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2020. 296 pp. Appxs. Biblio. Index. $27.95.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Heck, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve

There is no shortage of unit histories written about World War II. Some, such as Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers, are epic and sweeping in their scope, touching on timeless themes, courageous events, and individual participants that tie their narratives to the larger course of the war. Others, lamentably, are largely forgettable. The Fighting Corsairs is decidedly among the former. Jeff Dacus, a retired Marine Corps master sergeant, offers an engaging portrayal of a Marine Corps fighter squadron (VMF) during World War II that is lively and well-researched and does an admirable job of balancing the story of the men, mission, and machines. This book deserves a place on the shelves of those interested in squadron operations and aviation leadership in combat.

Dacus started researching the book in the 1980s, when many of the members of VMF-215 were still alive. Indeed, the interviews he conducted and letters he exchanged form the basis of the book. Additional oral history interviews from various sources supplement his secondary-source base. This focus on personal history helps personalize the tales related and put the reader in the briefing room, cockpit, and billeting with the aviators.

Starting with the formation of the unit on board Marine Corps Air Station Goleta, California, the pilots immediately take center stage. The aviators of VMF-215 represent a cross section of the Marine Corps officer class in early World War II. Some had previous aviation experience, others had none. Most joined the Marine Corps after Pearl Harbor, and all were eager to fly and fight the Japanese. Like many early war squadrons, VMF-215 initially lacked facilities, aircraft, and experienced pilots. Squadron leaders emphasized training and cooperation in the air, which paid dividends when the unit arrived in the Pacific.

Finally receiving their F4U Corsairs in January 1943, the squadron was transferred to the Pacific that summer, eventually arriving at Guadalcanal, where they launched their first missions. Dacus provides a sortie-by-sortie account of the squadron’s operations, following pilots and sections through uneventful aerial patrols and combat action with equal aplomb. His vivid writing presents the pilots and their struggles with the weather, the Corsairs, and the Japanese. By the book’s conclusion, readers will feel as if they know the men of the squadron.

Pilots in VMF-215 were required to complete three six-week tours. Many of their sorties were against Japanese positions in and around Rabaul. The Corsairs escorted a variety of Allied bombers striking Japanese shipping, airfields, and ground installations at that strategically vital target. These flights were not without losses for the squadron, which Dacus recounts in emotionally effective language. Some pilots were killed in action, others disappeared without a trace. Regardless of how they were lost, readers will be able to sense the impact on 215. The squadron finished flight operations in early 1944 and many of the pilots returned home, though some remained to finish their tours with other squadrons.

The book is amply illustrated with photographs from both squadron members and the Marine Corps’ official archives. Maps, some scans from official publications and others created for the book, help place the airfields and targets in context. An afterward covers the post-combat career of many of the pilots and the eventual fate of the squadron. Notably absent, however, are the enlisted Marines of the squadron. Some of that can be attributed to the fact that the ground crews were split from the pilots on their arrival in the Pacific, only reuniting briefly in early 1944 as the main body of pilots returned stateside. Nevertheless, the experiences of these Marines would be a valuable addition to the story of VMF-215 and help flesh out the experience of a Marine squadron during World War II.

Dacus has crafted a masterful narrative that frames and follows the creation of VMF-215 from inception to the conclusion of combat operations. The book has a place among other classic works on Marine Corps aviation, such as Gregory “Pappy” Boyington’s Baa Baa Blacksheep and Bob Stoffey’s Cleared Hot! As the Marine Corps continues with its Force Design 2030 efforts and new aviation squadrons are created to fly in the Indo-Pacific, leaders at the squadron level would do well to read The Fighting Corsairs to understand how their predecessors formed, trained, and conducted combat operations.

LtCol Timothy Heck is a joint historian with the Marine Corps History Division. He is the deputy editorial director at the Modern War Institute at West Point and the coeditor of On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Marine Corps University Press, 2020).

The Union Blockade in the American Civil War: A Reassessment

Michael Brem Bonner and Peter McCord. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2021. 217 pp. Appxs. Notes. Index.$45.

Reviewed by Craig L. Symonds

Just how much effect the Union blockade of the Confederacy had on the outcome of the American Civil War has been a topic of discussion and disagreement among Civil War scholars almost since the end of the war in 1865. The Union poured enormous resources into the blockade, expanding the U.S. Navy from 42 ships to more than 600. Yet, in spite of that, Confederate blockade-runners continued to run through the blockade until the very end of the war. Most historians (including this reviewer) have argued that the blockade clearly had some effect, but that measuring it with any specificity or certainty is difficult, if not impossible. The authors of this slim volume seek to find more specific answers.

They attack the question topically with chapters on diplomacy, economics, psychology, and effectiveness. The chapter on diplomacy is especially useful as they parse the legal nuances between “blockade” and “port closure” and describe the “delicate diplomatic situation” with Britain that was triggered by President Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation of a blockade. Also valuable is the chapter on the psychological effect of the blockade on the Southern population, which they explore by referencing the private diaries of a dozen or so prominent (and a few less prominent) Southerners. Whatever the economic impact, they conclude, the blockade was “an ever-present aspect of the Confederate social psyche.”

Less convincing is their assertion that because the number of successful steam-powered blockade-runners actually increased slightly between 1862 and 1864, the blockade did not have a deterrent effect on merchant shippers. They note that even though the number of blockading ships increased dramatically in those years, so did the technological and operational sophistication of the blockade-runners who were not deterred from making the attempt. The important comparison, however, is not between 1862 and 1864, but between prewar trade levels and wartime trade, which shows a decline in cotton exports (for example) of more than 90 percent. If daring blockade-runners continued to try their luck into 1865, the existence of the blockade nevertheless deterred more conventional shippers from even trying to run it at all.

The authors reiterate some of their key points frequently, often in similar language, so it sometimes feels repetitive, and there are occasional digressions, such as the inclusion of biographical sketches of several well-known individuals who ran the blockade. Still, their effort to challenge historical assumptions is both courageous and valuable.

They conclude that “The existence, performance, and sheer scale of the blockade was an important factor in Union victory,” though just how important remains unresolved. But then, as they note, “Historians . . . must argue about something.”

Mr. Symonds taught history at the U.S. Naval Academy for 30 years. He is the author of ten books on naval and Civil War subjects, including Lincoln and His Admirals.

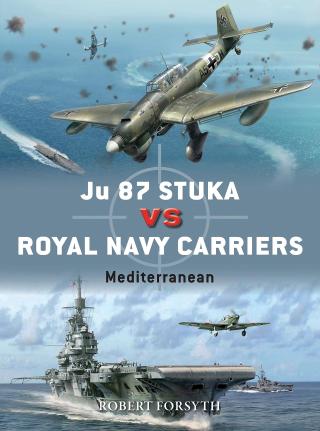

Ju 87 vs Royal Navy Carriers Mediterranean

Robert Forsyth. Oxford, U.K.: Osprey Press, 2021. 80 pp $22.

Reviewed by Chris Timmers

Thumb through any book of World War II combat aircraft and you will find planes whose performance, design, or silhouette are part of aviation history. The Messerschmit 109, the P-51 Mustang, the British Spitfire, or the Japanese Zero all occupy a place of prominence in this inventory of war birds, but no aircraft from this war makes the heart skip a beat or causes the eye to focus like the inverted gull-winged, fixed landing gear Sturmkampfflugzeug—or Stuka for short.

The Stuka was a dive bomber intended to hit targets with a precision unmatched by other aerial munition systems and certainly superior to horizontal bombing.

The war at sea quickly accommodated air power. In 1939 sea power was largely regarded as a function of surface ships and, with advent of submersibles, submarines. A new platform had been adopted to bring war, in this case air power, to an enemy: the aircraft carrier. With the increasing belligerence of Nazi Germany and imperial Japan, and war looking more and more probable, Great Britain and the United States set about building ships that could transport aircraft across oceans.

Robert Forsyth, a noted aviation writer and historian, details the development and combat performance of both the carrier and dive bomber in a book that is sure to both enlighten and entertain. With the Stuka’s record in western Europe and, later, in the Soviet Union, it seemed only natural to adapt it to seaborne targets. He speaks with authority in detailing the training of Stuka pilots and their “rear seat” gunners. Likewise, his discussion of carrier defenses and antiaircraft defenses focus on the types of munitions, the caliber of weapons, and the work in both building new carriers and retro-fitting cruisers with makeshift flight decks to handle tactical aircraft’s’ landings and take-offs.

In 1931, a German World War I pilot, Ernst Udet, visited the Curtiss Wright plant in Buffalo, New York, where the Curtiss Hawk was built. He was so impressed with the performance of the aircraft (he flew one himself) that he secured permission from the Reich Minister for Aviation to purchase two of the U.S. dive bombers. Test results and evaluations of the Hawk were unimpressive to the Germans, but Udet was an indefatigable champion of the dive bomber and development of one continued. At the end of 1936, three new Ju 87s arrived in Spain as part of the Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion, to offer support to Francisco Franco’s forces in that country’s civil war. Thus the legend of the Stuka was borne.

But there are important addendums to the legend. Specifically, the Royal Navy’s carriers in the Mediterranean were fitted with armored decks and it took between 10 and 20 dive bomber attacks on a single carrier to do any damage. Damage from Stuka attacks did contribute to the removal of HMS Indomitable, Illustrious, and Formidable for periods of time, thus eliminating three powerful aviation assets from the Royal Navy. But, it must be noted that during the course of World War II not one British aircraft carrier was sunk in the Mediterranean by Stukas. The only carrier the British did lose, HMS Eagle, was sunk by a U-boat.

Another little-known fact was that the Stuka in horizontal flight was a relatively slow aircraft (200 mph) compared to the British Spitfire (355 mph). Stuka attack groups required local air superiority to be effective (as they had in Poland and France).

In attacking seaborne targets, the Stuka had to rely on engaging slower moving merchant ships; they were not as effective against faster, more maneuverable warships.

In summary, readers know, thanks to Forsyth’s research, that in the one-on-one battle between British carriers and German Stukas the Royal Navy was the clear winner.

Mr. Timmers, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, is a freelance writer specializing in military affairs. He has served with the 82d Airborne Division and the 3d Infantry Division and was a liaison officer with the German Army’s 4th Infantry Division.