The National Museum of American History has several artifacts from the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 7 December 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Perhaps the most unique of these is a Japanese Type 97 torpedo gyroscope recovered from the midget submarine I-22tou. More than 80 years after being pulled from the bottom of Pearl Harbor, the gyroscope’s gimbals and rotor are still balanced and spin freely at the touch of a finger.

As part of Japan’s ambitious Pearl Harbor operation, Operation Shinki No. 1 (Divine Turtle Operation No. 1) would send five modified Type A midget submarines, designated as the Special Attack Unit, into the harbor on the morning of 7 December to launch attacks between the two waves of air attacks. Two men operated each 78-foot submarine, armed with two Type 97 17.7-by-220-inch torpedoes. With a 772-pound explosive warhead, the Type 97 theoretically would give the midget submarines formidable punch.

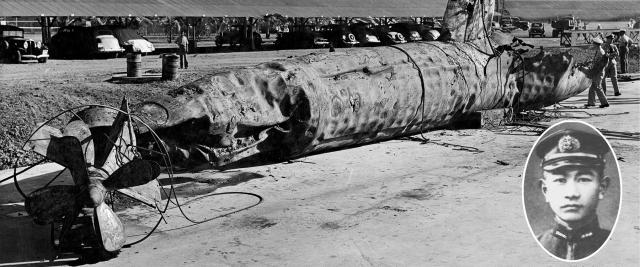

Lieutenant Naoji Iwasa (pictured here) led the five midgets into battle. Those midgets that survived would attempt to exit the harbor and rendezvous with the mother submarines off Lanai Island. Iwasa’s boat, I-22tou, launched just after midnight on 7 December, approximately nine miles from the harbor entrance. Joining Iwasa in the cramped confines of his boat was Petty Officer First Class Naokichi Sasaki.

At 0755 the first wave of Japanese carrier aircraft began strikes on Oahu. By 0830, the destroyer minesweeper USS Zane (DMS-14) reported sighting an enemy submarine 200 yards astern the repair ship Medusa (AR-1). This report reached Lieutenant Commander William P. Buford, commanding the destroyer Monaghan (DD-354). Minutes after the Zane’s report, the minelayer Breese (DM-18) and seaplane tender Curtiss (AV-4) opened fire on a sighted submarine periscope at 0836. A minute later, the Monaghan also sighted the submarine’s conning tower, and Buford ordered flank speed, intent on ramming the enemy boat.

I-22tou fired one torpedo at the Curtiss, which missed and struck a dock. The ship in turn hit the conning tower with two 5-inch shells, one of which passed clean through at 0840, decapitating Iwasa as he likely aimed through the periscope.

With the Monaghan steaming toward the submarine, either Naokichi or Iwasa in his final breath turned their boat toward the U.S. destroyer and fired. The last torpedo passed within 50 yards of the Monaghan’s starboard before hitting Ford Island. Within seconds, at 0843, the Monaghan struck a glancing blow on I-22tou and dropped two depth charges. The massive explosion blew the submarine back to the surface before she settled 30 feet below. The explosion lifted the Monaghan’s stern out of the water, and the destroyer lost control before hitting a derrick barge.

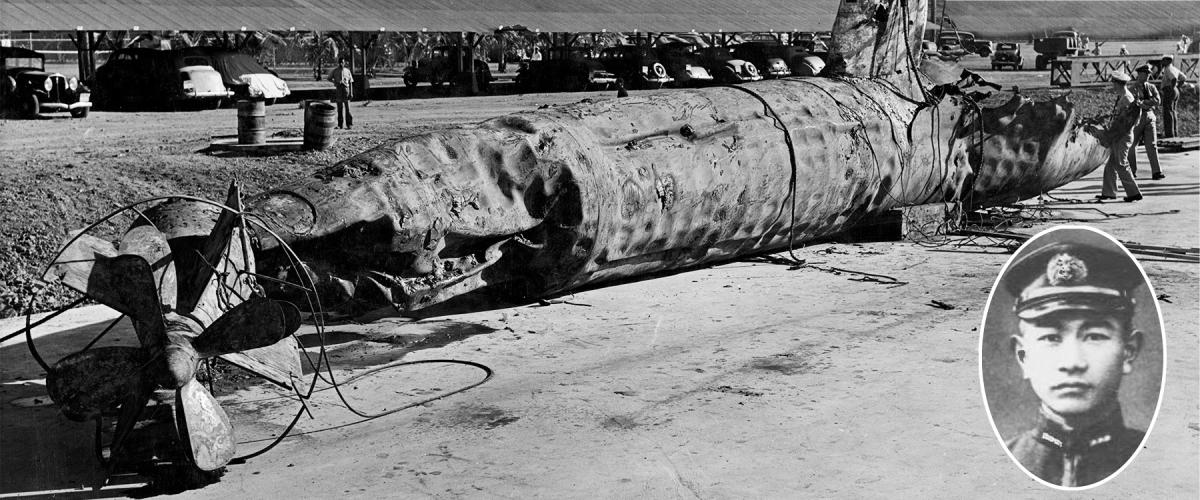

On 21 December, a naval salvage party raised I-22tou’s smashed remains from the bottom of the harbor with a crane and barge. The mangled remains of Iwasa and Naokichi remained entombed in the boat, her bow section completely blown apart. Both sets of remains would be removed and buried in Honolulu.

The Monaghan’s ramming had left visible damage along the boat’s aft hull. Naval Intelligence removed materials from the boat, and other usable components were removed to replace those on board the captured I-24tou. The remains of the boat became fill for an expansion of the S-1 submarine dock and lay there today beneath a parking lot. A Japanese naval lieutenant’s insignia, believed to be Iwasa’s rank insignia from the boat, was recovered and repatriated to Japan in March 1947. This insignia is now in the collections of the Yasukuni Shrine.

Among the items recovered by Naval Intelligence and souvenir-hunting sailors was a small wooden box marked on the lid “Box for Gyro Stabilizer.” Inside the box was a spare Type 97 torpedo gyroscope and assorted small parts for maintaining the device. At some point early in the war, naval personnel gave the cased gyroscope to Rear Admiral William R. Furlong, who commanded the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard after the attack. The case has battle damage from either a bullet or shell fragment. On 19 December 1960, almost exactly 19 years to the day I-22tou rose from the bottom of the harbor, Furlong donated the gyroscope to the Smithsonian Institution. When removed from its case and the rotor unlocked, the gyroscope spins just as effortlessly as it did in December 1941.

—Dr. Frank A. Blazich Jr.,

National Museum of American History