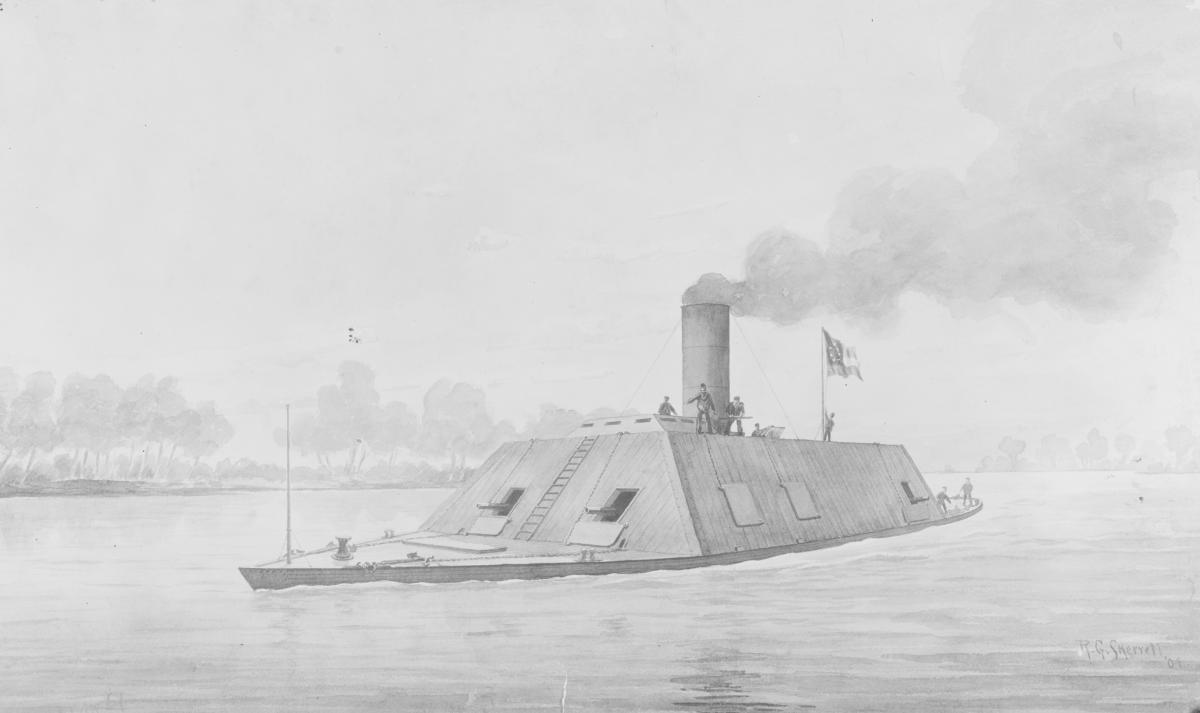

Any commander of any ship worth his or her salt will impress upon the crew, most emphatically, that “the devil is in the details,” and much personal anguish (in descending order of rank and increasing level of severity) awaits any junior officer, chief, petty officer, or seaman who lacks sufficient “attention to detail.” As a case in point, the saga of the CSS Arkansas illustrates the truth of this dictum and its relevance in today’s technologically advanced Navy.

Construction began on the casemate ironclads CSS Arkansas and Tennessee at Fort Pickering, just below Memphis, Tennessee, in October 1861. Scheduled for completion no later than 24 December, difficulties locating and transporting lumber, armor, boilers, marine engines, and heavy naval guns severely delayed construction. So humble an item as nails were obtained only by an appeal to the governor of Mississippi. Oakum could not be found anywhere, for any price. Cotton served as caulking. With materials finally in hand, shortages of skilled labor caused further delay. Appeals to the army to release carpenters and ironworkers fell on deaf ears. Leaving the Tennessee unfinished, the builder, John Shirley, concentrated all available manpower on the Arkansas.

When news of the fall of New Orleans reached Memphis, the senior naval officer for the area panicked. Union forces would not approach for over a month. Nevertheless, he ordered the Arkansas removed to Greenwood, Mississippi, and the Tennessee to be burned on her stocks to prevent capture. The Arkansas languished at Greenwood until Lieutenant Isaac N. Brown, her new captain, arrived. Reporting for duty, Brown found an incomplete hull, engines in pieces on the deck. and guns without carriages. Railroad iron intended for her armor lay at the bottom of the river, the barge containing it having sunk.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

A 27-year Navy veteran and a man of enormous energy and an indomitable will, Brown knew how to get things done. Recovering the railroad iron, he ordered the Arkansas towed to Yazoo City, Mississippi, where construction facilities were somewhat better. Driving his crew, the civilian workers, and Army labor enlisted for the effort, he saw to it that the Arkansas got underway under her own power five weeks later.

With 60 soldiers to help crew the gun deck, the Arkansas steamed down the Yazoo River on 14 July 1862 toward Vicksburg to face the combined Union fleets of Commodore David Glasgow Farragut, Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, and Commander David Dixon Porter. On 15 July the Arkansas engaged, heavily damaged, and scattered the ironclad Carondolet, the wooden gunboat Tyler and the ram Queen of the West, which had been sent to intercept her. Soon after the Union fleet of about 20 ships hove into view. Captain Brown described the sight as “a forest of masts and smokestacks.”

Ringing up full speed, the Arkansas smashed through the federal fleet, taking grievous damage but giving much more. Surviving the gauntlet of enemy ships, the Arkansas tied up at Vicksburg to the sound of wild cheering. Elated citizens rushed to board her but recoiled in horror at the sight of the carnage on her gun deck. Awash in blood and brains and body parts, the interior of the casemate resembled a slaughterhouse or a scene from Dante’s Inferno.

(Naval History and Heritage Command0

For the next week the Arkansas endured repeated attacks from the humiliated Union fleet. Her crew dwindled to 20 able-bodied men, but she survived each attack, taking and giving great damage. Unable to destroy the Arkansas, and with water levels on the river dropping, the Union fleet dispersed. Davis retreated to St. Louis; Farragut retired to New Orleans. They would not return for four months. The first siege of Vicksburg was over.

In the interim, the Arkansas was lost. Major General Earl Van Dorn ordered the Arkansas to support a land attack on Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Steaming downriver, both engines failed within sight of the federal fleet, and the Arkansas drifted ashore. Unable to move or bring her guns to bear, the Arkansas was helpless. Under heavy fire from the USS Essex, her crew opened the magazines, scattered powder and shells about the gun deck, fired her, and abandoned ship. Breaking free of the shore, she drifted downriver with Union vessels following at a respectful distance. After an hour she exploded, raining debris on the Essex and others.

Consider the possibilities if the Arkansas had survived and had been present when General Ulysses S. Grant and the Union fleet returned to Vicksburg in 1863. Consider the possibilities if both the Arkansas and Tennessee had been completed in a timely manner and had been available to defend Memphis in early 1862. For the want of common iron spikes, history literally turned on a lack of nails. The devil is, indeed, in the details.