The Italian city of Pisa, famous for its Leaning Tower, also offers visitors one of the largest and most interesting maritime museums in Europe. Called in Italian Le Navi Antiche di Pisa, the museum opened in 2019 with modern exhibits in an ancient building.

Located on the Arno River, Pisa was an important Etruscan and Roman port and shipbuilding center from 600 BC to 600 AD. During these 1,200 years, floods occasionally inundated the port, burying ships and their cargoes in deep mud. Some 30 wrecks lay forgotten until 1998, when construction for a railway station revealed them. Nautical archaeologists excavated the site for 17 years, completing their work in 2015.

Today, the unearthed ships and artifacts fill a renovated 16th-century warehouse built by the powerful Medici family. Eight galleries interpret the ships, artifacts, and wreck sites; they give a fascinating look into Pisa’s origins, nautical archaeology, shipbuilding, Mediterranean trade, sailing and navigation, and a sailor’s life.

The centerpiece of the museum is the Ship Gallery, a great hall in which visitors will see the preserved timbers from five different vessels dating from the 2nd century BC to the 6th century AD. Primary among these is the Alkedo, a 20-foot yacht propelled by a 12-oar crew and a sail. Because her name board was recovered, the Alkedo, which dates to the 1st century AD, is probably the oldest surviving vessel to which a specific name can be attributed.

Elsewhere in the Ship Hall are the substantial timbers of a 5th-century BC horse-drawn sand barge used on the Arno River. The museum credits it as being the earliest-known example of plank-on-fame construction. Other vessels on display include a 3rd-century AD traghetto (ferry), a Roman lintre (pirogue), and a 2nd-century BC cargo vessel.

The Pisan ships were saved and are on display because of the difficult and precise work of nautical archaeologists. A display shows the equipment and techniques required to document and preserve a wreck. So careful was the archaeologists’ work that visitors will see the skeletons of a sailor and his dog, side by side, as they were found in the ancient mud.

The Navigation & Sailing Gallery offers a rich display of maritime equipment, including a large 2nd-century AD anchor, oak blocks (nautical pulleys), remnants of ancient sails and rigging, and a ten-foot tiller from a cargo ship. Wayfinding was challenging, and errors could result in shipwreck; a blue-domed mini-theater introduces visitors to the techniques of Roman navigation. Running aground wasn’t sailors’ only fear; they also worried about their fate at the whims of the gods. A 2nd-century BC urn depicts Ulysses and the Sirens as the creatures seek to lure him to his destruction.

Another maritime superstition appears in the Sailors’ Life Gallery. Sailors have long believed that placing a coin under the mast of a vessel will ensure her good fortune at sea. A bronze sestertius, bearing the image of Augustus Caesar and found under the mast step of the Alkedo, verifies the ancient roots of this tradition.

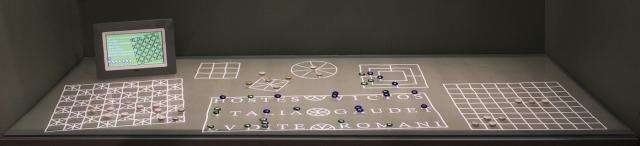

The Sailor’s Life Gallery displays what may be the oldest known (3rd century AD) sailor’s sea chest; its contents included 170 coins, a medicine jar, fire-starting materials, and a pen case. Elsewhere in this gallery visitors will discover a sailor’s leather jacket from the Alkedo, Roman wooden sandals, belt buckles, and the poofy top of a woolen watch cap. A reproduction galley shows pots, jugs, and a cooking stone. The board and dice games that entertained sailors are also on display.

Visitors will appreciate the excellent interpretive panels in Italian and English. Numerous videos, photographs, and illustrations make it easy to understand seagoing life and trade in ancient times.

Mr. Galvani had a 33-year career in museums and served as director of three. He also was a surface warfare officer in the Navy and retired with the rank of captain. He lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington.