A cool autumn day, 24 November 1859 witnessed the birth of a new type of warship at the Mourillon Arsenal, Toulon, France. Her name was the Glorie and she was the brainchild of the French naval architect Henri Dupuy de Lome. De Lome had studied shipbuilding in Britain and it was with new conviction that he returned to France in 1844. He had seen the SS Great Britain being built in Bristol and was now convinced that the future of naval warfare was steam-powered, ironclad vessels. History best remembers the American ironclads of the Civil War—such as the Monitor or the Merrimiac—but these evolved from earlier, more powerful European ironclads.

France’s Glorie

Britain had “ruled the waves” of Europe for many years, confident in its naval superiority, but by the 1850s, all this was about to come under serious threat. The Crimean War (1853–56) had shown many that wooden warships were now obsolete. The development of the Paixhans gun, a rifled cannon designed by Paixhan in 1822–23 to fire explosive shells, had, alongside new rifled arms, proved devastating against wooden ships. In response to this threat, the British and French had developed ironclad floating batteries for the bombardment of Russian forts in the Crimean. These had proved impervious to Russian gunfire and represented a key point in the development of naval warfare.

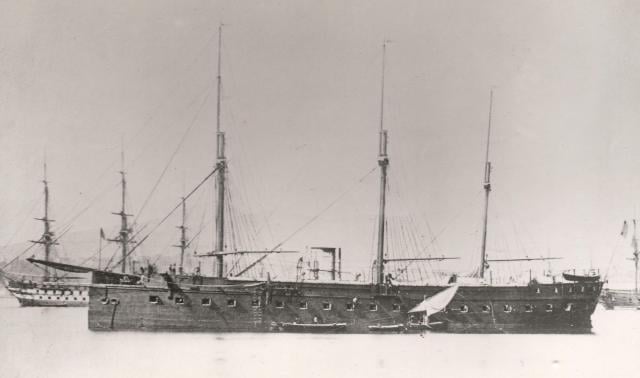

The French navy was quick to realize that change was inevitable and they began to experiment with different ways to armor their vessels. The construction of the French ship Glorie began in April 1858 and she would feature a groundbreaking design. Her wooden hull would be encased in iron plate and she also was to have steam propulsion by means of an internal steam engine system. The Glorie was designed to be a broadside ironclad, with her guns arrayed in long side batteries, much as they had been on wooden ships for the previous 500 years. She was, however, not to be called a ship-of-the-line; rather she was an armored frigate, the term “ironclad” did not yet having any meaning.

De Lome encountered several difficulties with his design for the Glorie, not least of which was the lack of French factories capable of manufacturing the iron plate required and, as a result, the wooden hull was 45 centimeters (cms) thick and the iron plate was only 12 cms thick, much thinner than De Lome originally had planned. The Glorie was therefore not a true Iron clad vessel, but she was well on her way.

Her construction was rushed on the insistence of Napoleon III, ruler of France at the time, so the timber specification did not meet the standards usually employed for naval vessels. This meant the Glorie and her sister ships, the Invincible and Normandie, frequently required serious structural repairs. Their construction itself was typical of ships at the time in that it gave no thought to the comfort of the crew—ventilation was a serious issue as there were no provisions made for the steam and smoke to leave the vessel. The Glorie was armed with 36 16-cm rifled guns, designed to smash through lesser wooden vessels and, once inside, to explode to cause maximum damage. She was 77.8 meters long and displaced 5,630 tons, but an important flaw in her design was exposed during her sea trials: She sat so low in the water that her gunports were just 2 meters above the water. However, more important, during these trials the Glorie also was fired on, and none of the French rifle muzzle-loading guns’ 7.1-inch shots penetrated her hull. She was, for now, invincible.

Britain’s Warrior Response

By the time construction on the Glorie was well underway, word had already reached Britain of her design and construction, and the admiralty knew that once complete she would make every other vessel afloat obsolete, including Britain's wooden-hulled ships-of-the-line. This would leave Britain exposed to the threat of invasion. The situation was serious enough for Queen Victoria to personally inquire of the admiralty what exactly they proposed to do to ensure Britain’s navy could do its job.

Britain previously had experimented with iron-hulled ships, but found them untenable and susceptible to gunfire. They had, however, like the French, continued to conduct experiments, and by the time Glorie was launched they had come to the conclusion that the iron cladding would have to be at least 4 inches thick to withstand modern gunfire. The British admiralty knew they had to use this knowledge to neutralize the French threat and responded by asking for commercial proposals to design and build an ironclad warship.

The initial design was proposed by Sir Baldwin Walker, but the responsibility for making a final blueprint fell to the chief conductor of the navy Isaac Watts, and chief engineer Thomas Lloyd. As a result, HMS Warrior and her sister ship, the Black Prince, were commissioned. Unfortunately, the royal dockyards had no experience building ironclad vessels, so they were to be built on the Thames by the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company and Clyde respectively.

First and foremost the Warrior and Black Prince were designed to be able to defeat the Glorie in a sea battle. To this end, they were built to be faster, better protected, and better armed than their French counterpart. The Warrior was fitted with a fully ironclad hull; in 1861 the Warrior’s 4.5-inch thick armor was subjected to extreme testing and ruled “practically invulnerable to the ordinance at the time in use.” The Warrior also had steam propulsion and 4 8-inch rifle muzzle-loading guns, 28 7-inch rifle muzzle-loading guns, and 4 20-inch breech loaders. However, she was not designed to stand in a naval battle line, as the Glorie was. The Warrior instead was supposed to be fast enough to outrun other vessels and force them into engagements on her terms. With this aim in mind, the Warrior was equipped with a single shaft propulsion system, powered by a Penn horizontal trunk steam engine and ten boilers, which together could generate 5,627 indicated horsepower, meaning the Warrior was a true oceangoing vessel that could reach speeds of 141 knots. In addition, she still bore sails to enable additional speed as well as protection. She was the first ship to combine all of these modern innovations in one vessel, and as such represented the beginning of the age of “true” ironclads.

The Race to Build an Ironclad Fleet

The Warrior was built very quickly. Construction began in 1859, and by August of that year, full-scale production of the iron required to complete her was well underway. Before she was ready, however, word reached Britain that the French were planning to build at least ten more ironclads. Britain did not have the finances to begin such a project, but these new French “ironclads” still, like the Glorie, featured a wooden hull. The admiralty took this on board, and as an interim solution, the newly built Royal Oak was fitted with iron plates on her sides. She was followed by eight other ships that featured this improvised design.

Two years later, on 29 December 1861, the Warrior was ready to launch. According to contemporary records that winter was particularly cold, and the Warrior’s iron hull had frozen to the slipway, where tugs, hydraulic rams, and workmen were required to free her. The Warrior was a new design and, as such, over the next few months she was subjected to a series of sea trials by the British Navy. The sea trials exposed a number of design issues and in November 1864, the Warrior was refitted and her armament was upgraded to the latest muzzle-loading guns, as her initial guns had proved problematic to use at sea.

However, in June 1862 the Warrior was put to sea. When the Warrior launched, to patrol the Channel ports, she received a huge amount of attention and, in 1863, the ship received more than 300,000 visitors in the space of 12 weeks. People flocked to see this miracle of engineering, the embodiment of the future of British naval warfare.

The Warrior, alongside her sister ship the Black Prince and counterparts Defence and Resistance, now formed the nucleus of Britain's new ironclad fleet. The Defence and Resistance were identical to the Warrior except that their armored belts extended the full length of their gun decks, they also were slightly shorter, making them more maneuverable. They carried 16 guns and were slower, with a maximum speed of 12 knots. In a marked move away from traditional colors, the ships all had the same color scheme—they had ochre funnels, but the rest of the ships were black, except for a narrow white trim around the upper edges.

The Achilles soon followed in 1864, and in 1861 the admiralty ordered three larger vessels—the Minotaur, Agincourt and Northumberland—whose slightly modified design featured five masts, which was in theory to make them faster, but their sheer bulk mean that under wind power they were slow and cumbersome. These ships all together became known as Britain's Black Battlefleet.

The Warrior famously never fired a shot in anger. When she was launched, her very existence rendered every other vessel, including the Glorie, obsolete. The Glorie had been beset by problems since her launch, not least the waterlogging of her inferior timbers and by 1883 she was scrapped. The rapid evolution of Ironclad warship design though, for which she and the Warrior were partly responsible, meant both had started to become obsolete within ten years of their launch.

The Evolution of Ironclad Design

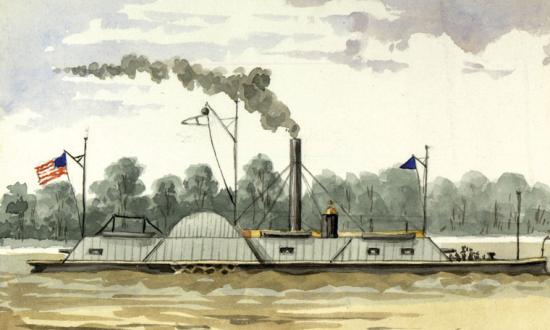

While the Glorie lead to the Warrior’s creation, Warrior’s launch ignited the evolution of European ironclad design, as other European navies sought to match her. The development of more powerful guns, in combination with the production of thicker iron plates meant that it now was possible to need a smaller number of guns and to protect them more effectively with thicker armor. With this in mind, the two areas in which this thicker plate was concentrated were above and below the waterline, where the threat to the magazine was at its greatest, and in front of the gun battery. This led to the development of a “box” to protect the ship’s guns. Without the need to protect a ship’s vast broadside, the ships could be lighter and more maneuverable. This new design was called a “central battery” Ironclad,—he equivalent of the American “casemate” terminology.

Britain's HMS Bellerophon was the first ship commissioned in 1866 with this new configuration. Edward Reed had taken over from Isaac Watts as chief constructor for the navy and he broke away from the previous plans to build more broadside ironclads. He envisioned smaller, better protected, and more maneuverable ships, and the move towards building “asemate ironclads’ was ordered

The Bellerophon also was fitted with a more balanced rudder, a development born out of the British Navy’s experience sailing ironclads. This, combined with her shorter length, meant that she could turn in half the time and distance of the Warrior. She also featured a newly developed deadly set of 10 9-inch muzzle-loading guns.

The Bellerophon represented a major step forward in ironclad ship design. Quickly, other European powers followed suit, and the 1860s and ‘70s saw an explosion in ironclad shipbuilding. The Italian Navy commissioned the Ironclad Venezia, and the Germans the mighty Konig Wilhelm. In response, by 1866 Britain had laid down the Hercules, a larger version of Bellerophon, and when the Northumberland and Minotaur launched the same year, they were, like Glorie and Warrior, already outdated.

The race was on to design better and more effective ships, wood was obsolete, and soon the future of ship design would be driven by innovation in the New World: The age of the ironclads had begun.

1. Appleton’s Encyclopaedia (1862).

2. Captains de Balincourt and Vincent-Bréchignac, Captain, “The French Navy of Yesterday: Ironclad Frigates,” F.P.D.S. Newsletter (1975), 26–30.

3. Richard May, HMS Warrior 1860 to Date: Owners Workshop Manual (Yeovil, UK: J. H. Haynes & Co., 2017).

4. John Wells, The Immortal Warrior: Britain’s First and Last Battleship (Hassocks, UK: Fisher Nautical, 1987).