The taking of trophies and the building of memorials to mark military victories has been common throughout the history of warfare. The English word “trophy” is derived from the ancient Greek tropaion, which was a display of captured weapons, armor and standards commemorating the defeat of an enemy.

Warriors took great pride in the trophies representing their unit’s triumphs in battle but many also wanted to record their individual victories over a foe. Headhunting and scalping were perhaps the most gruesome means for exhibiting defeated enemies. A less grisly practice in some cultures was to get special tattoos after vanquishing adversaries. Pulp Westerns often featured cowboys who sported notches on their holsters or revolvers to mark all the men they had gunned down. While probably rare, there are indeed documented cases of men notching guns, knives and ax handles to record kills. T. E. Lawrence is known to have added notches to his rifle for every man he shot during the Arab Revolt.

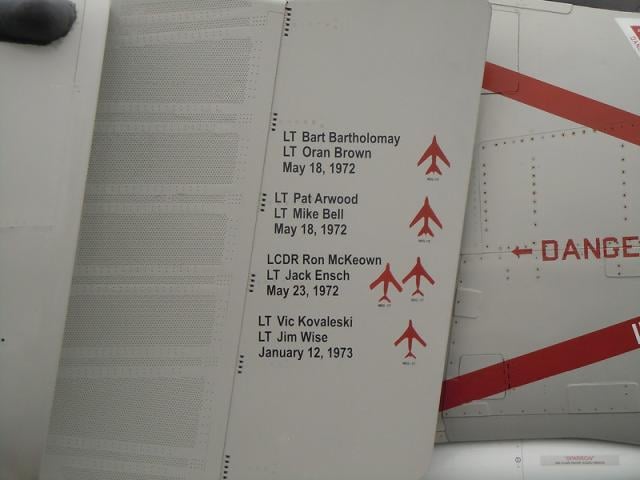

Pilots during World War I tracked their success over enemy aircraft as they sought to achieve enough victories to reach the status of ace. It was common for pilots to seek out the planes they shot down to retrieve a piece to keep as a trophy. In addition, squadrons began marking the scores of their individual pilots on a board at their base. These victory marks (also known as kill marks) were usually flags or insignia representing the nationality of the downed aircraft.

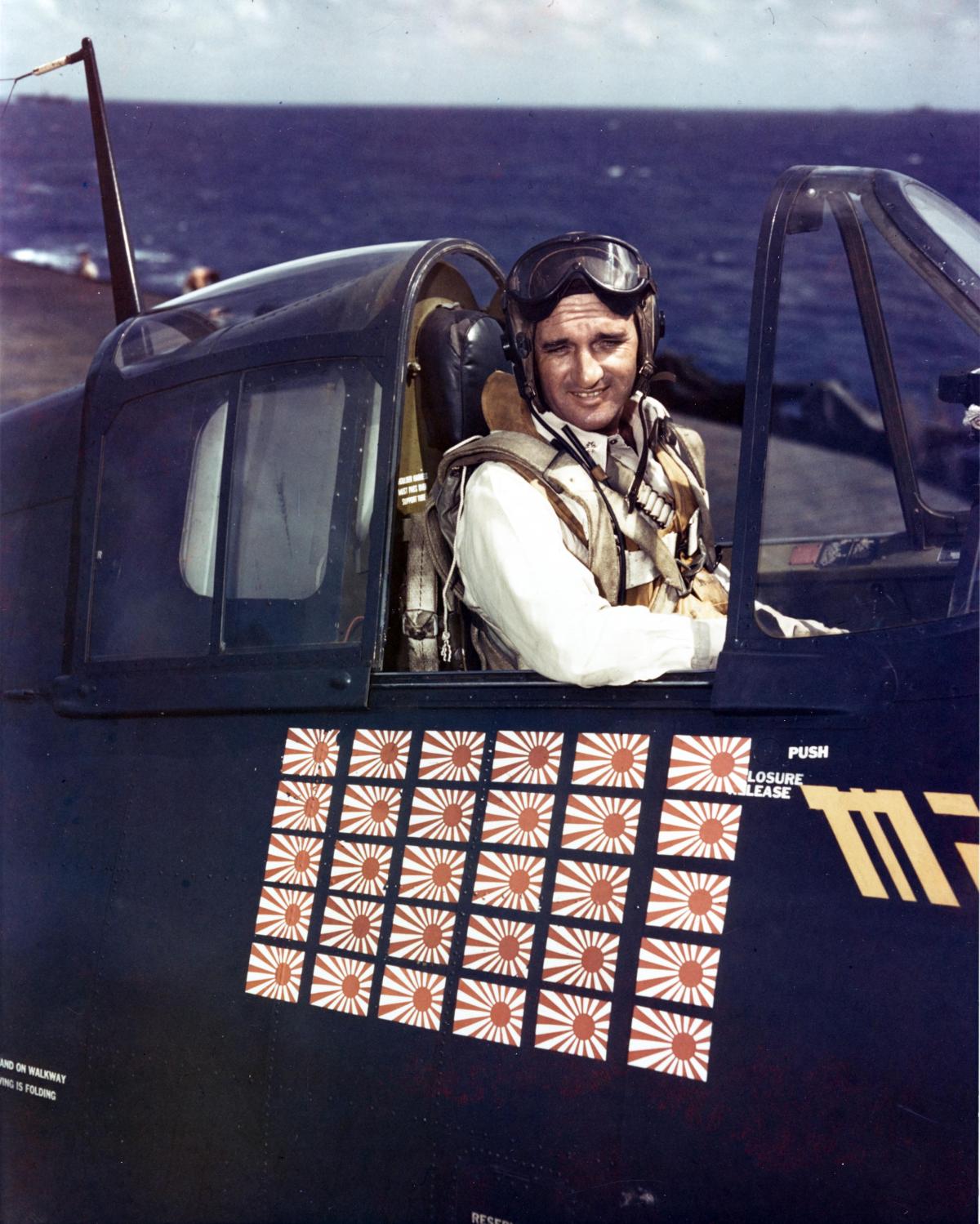

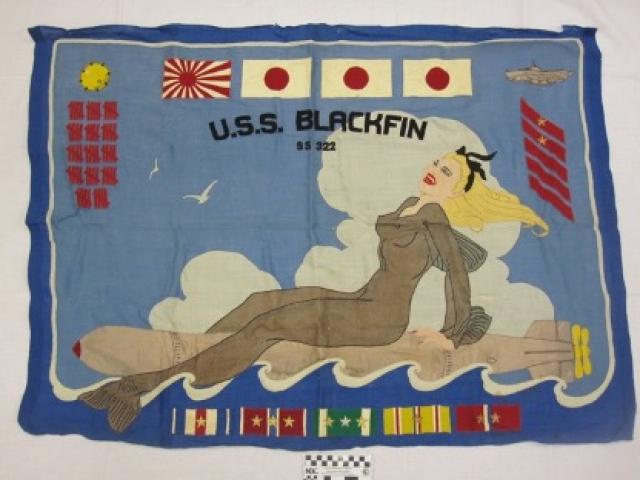

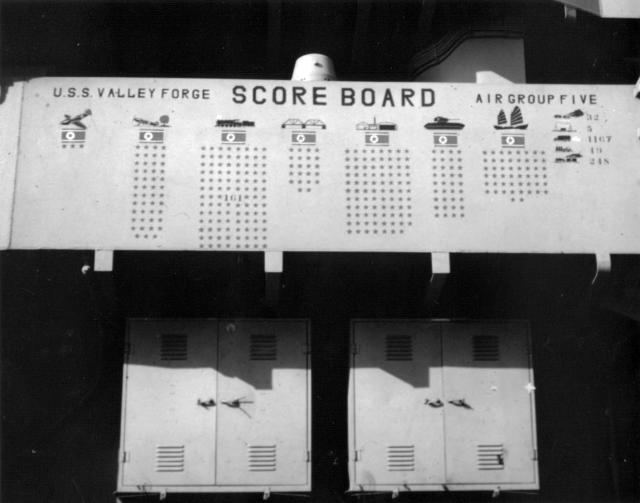

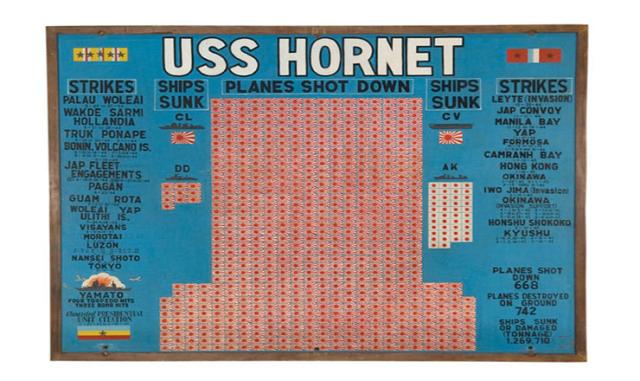

By World War II, the U.S. Navy had adopted the practice of adding marks directly to the fuselage of its victorious planes. The tradition was expanded so that ships also prominently displayed a variety of victory marks on a scoreboard, often depicting silhouettes of sunk enemy vessels. The U.S. sea services still use victory marks to signify successful engagements, many of which are quite unique. The following photos present examples of different Navy marks.

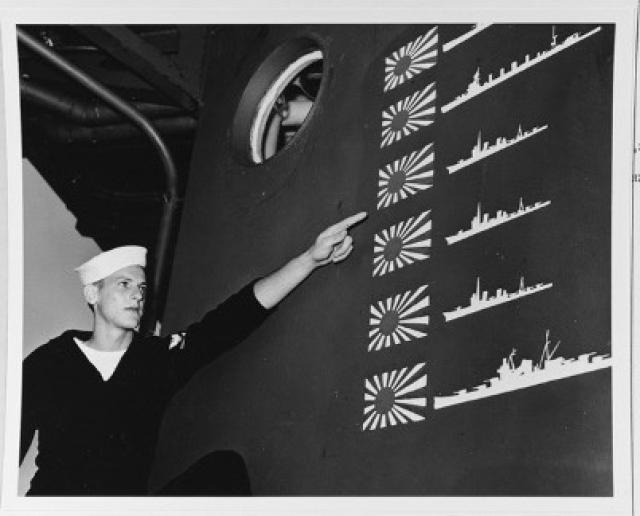

A sailor points to victory marks representing the destroyers and cruisers sunk by the USS Boise (CL-47) during the Battle of Cape Esperance in 1942. A later review determined that the scoreboard mistakenly overstated the actual number of ships sunk in the nighttime action.

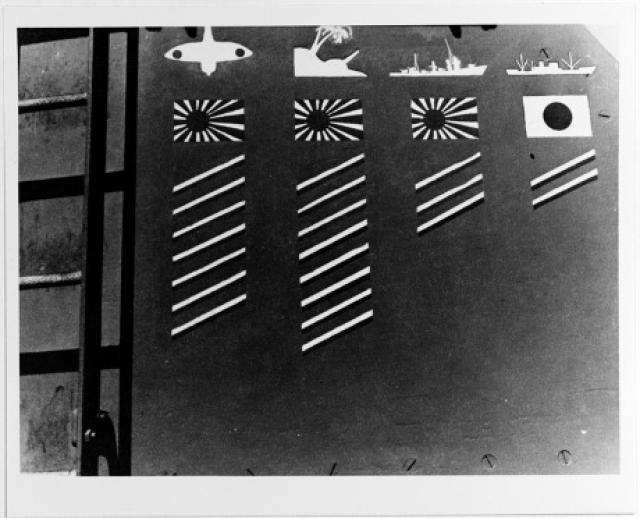

The second column of victory marks on the scoreboard for the USS Charles Ausburne (DD-570) commemorate shore bombardments.

The USS Cod (SS-224) has a victory mark for destroying the Dutch submarine 0-19. Although the Netherlands were an ally, the Cod had to prevent 0-19 from being captured by the Japanese after she became stuck on a reef in 1945. After taking on the Dutch crew, the Cod sank the 0-19. The Dutch crew was so thankful for being rescued that they later hosted a big party for the Cod, which resulted in another victory mark—a cocktail glass.

The USS Gurnard (SS-254) scoreboard has several Japanese flags with a single stripe in the middle to denote transports that were damaged but not sunk.

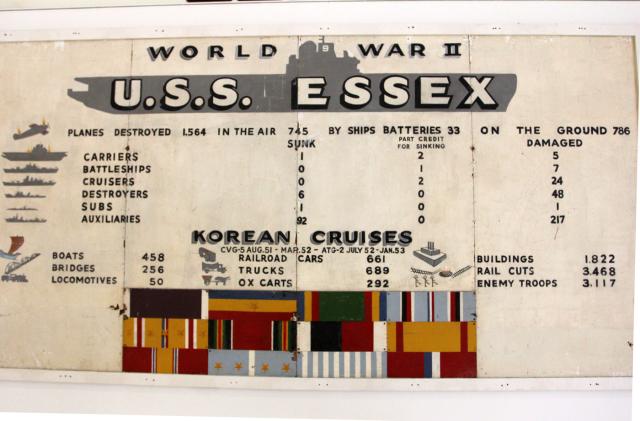

The scoreboard for the USS Essex (CV-9) now on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum includes victory marks for the bridges, trucks, and ox carts her planes destroyed during the Korean War.