On 13 September 1922, the USS Langley (CV-1) departed the Norfolk Navy Yard, steamed down the Elizabeth River, and docked at the merchant-ship end of the Hampton Roads Naval Base. In command was Captain Stafford H. R. “Stiffy” Doyle, who had reported aboard in June. The Langley had been prematurely recommissioned six months earlier to draw on operational funding to complete her conversion from a collier to the Navy’s first aircraft carrier. His executive officer, Commander Kenneth Whiting, had served as Doyle’s stand-in at the makeshift 20 March ceremony, which was capped by a swab pole—to which was affixed the commissioning pennant—being nailed into a flying-deck plank over the former collier Jupiter’s pilothouse.1

While at the carrier’s temporary berth, Doyle made final preparations for sea trials. On Saturday, 16 September, two Vought VE-7 and two Aeromarine 39-B biplanes were hoisted aboard. In addition, the command welcomed some newly reporting crew members, among them, Joseph Weller, who marked the occasion with the following diary entry:

Reported aboard at 5 PM. Was informed that I was the official gyro man. Me not knowing anything meaning of course the gyro end. Looked my job over. As a blacksmith I don’t imagine I will amount to much as a watch maker for it certainly needs one on this job.2

Weller was actually a bit more qualified to maintain the Langley’s gyrocompass than he would have us believe. Born in Waverly, New York, in October 1892, he had enlisted in the Navy in December 1913. Following boot camp, he completed electrical training at the New York Navy Yard and then served out the remainder of his first four-year hitch in the USS Florida (Battleship No. 30). With the United States now at war, Weller reenlisted and spent the first two-thirds of 1918 embarked in the Mississippi (Battleship No. 41) before drawing orders to the receiving ship at Norfolk, where he would finish out his second four-year tour.

Promoted to chief electrician a few months into his Norfolk tour, Weller also developed an intimate relationship with Yeoman (F) Adeline “Addy” McGrath. A native of Norfolk, McGrath had enlisted in the Navy in March. By the end of the year she would be pregnant. Discharged from the Navy in February 1919, she and her new husband, Joseph, would welcome daughter Dorothy Mae that August, and the couple had a son, Thomas, a year later.3

The domestic situation likely factored into Weller’s decision not to reenlist for a third tour, and the Navy honorably discharged him in April 1921. For whatever reason, Weller chose to rejoin the Navy in the summer of 1922. With his broken service, he did not enjoy the privilege of coming back at his old rank and rate. Instead, he apparently was tagged to fill one of the Langley’s three blacksmith billets slated for a second- and two third-class petty officers. Orders to the ship meant the new father would be able to spend time with his young family—at least in the near term.

At 1110 on Monday, 18 September, the Langley departed Norfolk to undergo sea trials. Weller recorded that yard workers embarked for the inaugural shakedown voyage to evaluate the equipment they had installed were apprehensive, as many feared that the ship’s high flying deck might cause her to capsize in open seas.4

Having gone north into the Chesapeake Bay, the Langley over the next two days steamed in circles to allow adjustments to her magnetic compass to be made. Down below in the gyrocompass room, Weller chronicled the compass calibration and noted on the third day out, “Still going in circles—getting dizzy now.” Back at the Norfolk Navy Yard, a false report spread that while swinging her compass off Tangier Island, the Langley had indeed capsized. To Weller’s relief, Doyle straightened out the ship’s heading on Thursday and Friday, allowing high-speed runs to test her unique electric-drive propulsion plant. When problems with the main condenser arose on Friday afternoon, the ship slowed to a stop and Doyle directed the crew to have a field day. A veteran of many such fore-to-aft ship-cleanings in battleships, Weller commented, “This don’t mean we go in the field and pick flowers.”

The next day, after Doyle inspected the ship anchored near Tangier Island, the captain authorized a little rest and relaxation. For many of the sailors, that meant grabbing fishing rods and boating over to the derelict hulls of what were once the second-class battleship Texas and the battleships Indiana and Alabama (Nos. 1 and 8, respectively). Now serving as target ships, the hulks were sanctuaries for schools of fish. Weller recorded a catch in the flooded forward magazine of the former Texas.5

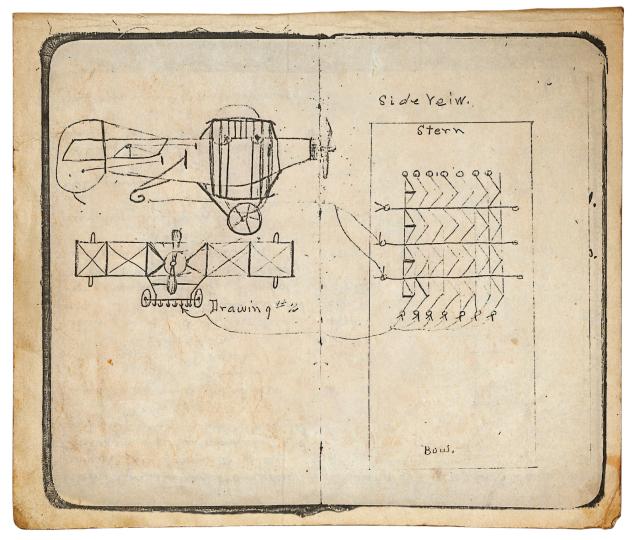

With the crew back on board, the Langley resumed her shakedown trials. On the flying deck, crewmen adjusted the arresting gear as an embarked aircraft, with Assistant Flight Officer Lieutenant Virgil “Squash” Griffin in the cockpit, taxied over a rather complicated trapping system developed and tested ashore by Lieutenant Alfred M. “Mel” Pride. As with modern carriers, there were cross cables. With the Langley, each cross cable extended off the sides of the flying deck and were attached to weights that could be adjusted to accommodate different types of incoming aircraft. As a precaution to prevent aircraft from sliding off the port or starboard side of the deck, Pride had added a British-based system of fore-and-aft wires that were raised off the deck by notched pieces of wood called fiddlebridges. A series of anchor-shaped hooks on the underside of a plane’s main landing gear axle would catch the wires. On the port side, deckhands pivoted out the ship’s single stack for simulated flight operations. The drills were occasionally disrupted by mail drops from aircraft flying out from Hampton Roads. Also arriving were reels of old movies, which would be shown on the well deck. Weller particularly enjoyed Charlie Chaplin’s 1917 classic Easy Street.6

Finally, on 28 September Doyle steamed his ship seven miles up the York River and eased to an anchorage near the mine depot’s dock. Ashore, an airfield had been constructed to support the forthcoming training. Meanwhile, Whiting hosted daily conferences to discuss the most basic of procedures.

How to determine the best wind? Smoke pots were placed on the forward flight deck. Weller wrote that the pots were set off by hitting their heads with a hammer “and throwing in a glass of water.” How to announce flight quarters? In an era when bugle calls rather than boatswain-pipe tweets informed the crew of daily routines, the selection of “Boots and Saddles,” the Army’s traditional call to mount cavalry, won out over test firing one of the stern 5-inch guns.

How to handle aircraft? The carrier’s officers and senior petty officers developed methods to move a plane about using a man on each wing tip and a third man controlling a tail dolly, all directed by a “plane captain.” Since radio had yet to become a fixture on aircraft, the question of how to communicate with an airborne plane that the deck was clear for landing operations was resolved by flying either a white (clear) or a red (not clear) flag at the aft end of the flight deck.7

To meet wind-over-bow requirements to launch aircraft from a fixed position, the Langley swung off her hook into the wind. Spread out around the carrier were five buoys anchored to the river bottom. With wind coming from a dominant direction, the carrier’s deck force attached a line from the stern back to the nearest anchor buoy.

With the carrier so positioned, Weller made the following entry for 3 October:

Testing landing gear. First plane with Griffin at wheel leaves deck. Fine sights. Machine up to speed. Trip holding block. Start off. Reaches end of deck. Drops about 10 ft. Rises and lands at flying field. No accident. Movies. End of a perfect day.

If Weller’s account is accurate, he just rewrote the history books, which have Griffin making the first takeoff from a U.S. carrier on 17 October.

On 10 October, four pilots attached to the Langley took off from the nearby airfield to practice simulated landings—approaching her stern and then applying speed to overfly the deck. Writing five decades later, retired Rear Admiral Jackson R. Tate recalled that Lieutenant Pride actually touched his wheels on the deck on one run before he applied power. Tate, who was an ensign at the time, recalled that Commander Whiting was not pleased. However, in his diary entry for that day, Weller wrote: “Four planes flying off, returning and just touching deck but do not land. Practice.”8

On 17 October, a large entourage watched as Griffin climbed into a VE-7SF cockpit, and, as he was preparing for takeoff, winches on the carrier’s stern pulled and released lines to the aft anchor buoys to adjust the ship’s heading into the wind. The plane was spotted well aft of the elevator amidships, and the tail was lifted onto a trough created by two short rows of sawhorses. The tail was held in place by a wire with a ring attached to the plane’s landing hook. At the tail end of the flight deck, the wire was fastened to a bomb-release mechanism. The propeller was hand-cranked to get the engine started, Griffin revved it up to 180 horsepower, and on signal, an operator triggered the release mechanism. The VE-7SF was airborne almost before it reached the midships elevator. Griffin then flew to terra firma, landing at the Hampton Roads Naval Air Station.9

Rear Admiral William Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), was on hand for the official first takeoff and subsequently boasted, “The air fleet of an enemy will never get within striking distance of our coast as long as our aircraft carriers are able to carry the preponderance of our air power to sea.”10

On the following day, successive launches by Ensign C. D. Palmer, Lieutenant Commander Godfrey DeC. “Chevy” Chevalier, and Mel Pride were recorded in the Langley’s deck log. Over the next week, the carrier’s young aviators continued to practice their approaches, mostly using the Aeromarine 39-Bs. On 25 October, Weller wrote: “All planes took off again landed at air sta. Preparing to make the first attempt at landing on deck. Movies Good.”

The next day, the Langley, having made all preparations for getting under way at 0630, began hauling up her starboard anchor. In the gyrocompass room, Joseph Weller turned on the ship’s gyrocompass, and, to his relief, it still worked. Departing from her York River anchorage at 0715, the carrier steamed into the Chesapeake Bay off the “Tail of the Shoe” shoal, just inside Cape Henry.

Ensign Tate tracked the morning events, writing, “At 10:50 started maneuvering ship to land plane, at various courses and speeds.” He then recorded, “At 10:59 plane A-606 piloted by Chevy circling ship.” Flying over the Langley’s stern in a 39-B, Chevalier looked down on the preparations for his landing. Finally, a white flag appeared, signaling him to approach the flying deck. His plane snagged the first cross wire and latched onto four or five of the fore-and-aft wires. Weller captured the scene:

Catching first set of cables, but having cut off the gun the plane slipped sideways. The weight at the tail threw the nose down causing a breaking of a propeller and standing on end. Poor landing in all by failing to keep nose clean.

The man who would get credit for the first landing on a U.S. aircraft carrier stepped down from his cockpit to a throng of well-wishers. Looking back at the flying deck, Weller lamented, “[He] took down all landing gear.” With mission accomplished, the Langley returned to Norfolk.11

The timing of the landing coincided nicely with the next day’s plans to celebrate the first “Navy Day.” For the event, the crew “dressed ship” by hanging signal flags from a line that extended from the bow up over the two telescoping masts and down to the stern. Some 1,500 visitors toured the ship that had just garnered attention in the national media.12

After two more days in port following weekend liberty, Weller energized his gyrocompass early on Wednesday as Doyle set the sea and anchor detail for an 0930 departure to return to the Yorktown anchorage, arriving just past midday. On Friday, with the arresting gear reset, the Langley set flight quarters, and Weller recorded, “Three planes landed in fine shape.”13

Buoyed by further news of the successful takeoffs and landings, Moffett wanted to see more of it for himself. On Sunday, 5 November, he flew to Hampton Roads and embarked in the Langley to observe an intensive week of flight operations as well as take advantage of the anchorage location to duck hunt. On Monday, Weller recorded Moffett observing Ship’s Bos’n Walter J. Daly flawlessly land and take off. The next day, Weller noted that the BuAer chief spent the morning at a nearby duck punt bagging 47 birds, “but he didn’t give me any.”

Moffett returned to witness the rigging of a dummy seaplane on a trolley-like contraption attached via a traveler to the catapult, which the crew had dubbed “Little David.” The aircraft’s twin floats rested in the device’s two wheeled wooden carriages. Built by Langley crewmen under the direction of Lieutenant Frederick W. “Horse” Pennoyer Jr., the carriages had a series of releasable hooks to secure the floats. The hooks would open, freeing the aircraft, once the trolley passed over two angle irons positioned near the end of the deck.14

Weller recorded that the contraption automatically released the dummy when it reached the end of the flight deck, and the unmanned aircraft actually rose about 15 feet and traveled forward about 75 feet before plunging into the York River “with a report like a 10-inch gun in action.” A recovery team saved the dummy, one wing of which had been torn off, for further use.

With the trolley removed, Doyle’s ship conducted additional flight operations. Weller noted that Griffin hooked the second set of cables, pulling the attached weights up 37 feet, and Pride’s softer landing, catching the third set of cables, caused the attached weights to rise only 21 feet. Both pilots had successful launches and landed ashore. Daly also had a successful trap and takeoff, initially dropping 20 feet below the flying deck level before attaining 300 feet in altitude and circling the carrier “when plane crashed to water.”15

The aircraft remained afloat, though the weight of its engine forced the tail, which Daly climbed onto, out of the water. After three hours, the plane was lifted aboard for examination and repair. Weller, looking over the damaged propulsion plant, speculated that the shock of the earlier landing, with its sudden halt, threw the engine out of line:

When leaving it was very hot. This caused the wrist pin in #1 cylinder to freeze to the crank shaft. Something had to go. This forced the entire cylinder to explode and, on the return, stroke forced the cylinder through the bottom of the crankcase bringing the engine to a sudden halt.16

The next day, after several successful landings and launches, Weller again observed a major mishap when Bos’n Anthony Feher crashed his aircraft on the Langley’s flying deck at 1600. The plane’s tailhook had broken away after catching one of the cables, and, Weller wrote, “Tony gave her the gun, trying to take off at once.” Unfortunately, the hooks mounted under the wheel axle had caught the fore-and-aft wires. As the aircraft shot forward, it was trapped to the flying deck until reaching the end of the wires brought the plane to a violent stop, “throwing the nose down, smashing the propeller at the hub, crushing all landing gear on plane,” and “pulling motor from body.” Apparently Feher was not securely strapped in and cracked his nose on the edge of the cockpit.17

Gusty winds on Thursday canceled flight operations, and on Friday the catapult, pulling the trolley device, again launched a dummy seaplane. With much of his diary dedicated to critiquing the films brought aboard, Weller began to note that movie call began to feature footage of the early landings and takeoffs. He noted the pictures were “run very slow so that all hands could observe the effects.”18

While the Langley was at her Yorktown anchorage, many of her pilots commuted in their aircraft to Norfolk for weekend liberty. Flying to Norfolk on Saturday, 11 November, Godfrey Chevalier used most of the gas stowed in his VE-7’s aft 12-gallon tank. The forward 10-gallon tank remained full. Unfortunately, the maintenance crewman who inspected the aircraft the next day was unfamiliar with the plane’s fuel tank arrangement, saw the forward tank was full, and reported to Chevalier that the plane was ready to fly.

Shortly after takeoff, with the engine still taking fuel from the near-empty aft tank, Chevalier lost power. Attempting to land in what appeared to be a meadow, he touched down in a mucky field, causing the plane to flip over. Two days after the accident, on 14 November, the pioneering aviator succumbed to his injuries at the naval hospital at Portsmouth, Virginia. Noting his passing, Weller observed the weather to be cloudy and rough—a reflection of the morale of the crew. Then, as if to facilitate a period of mourning, the rains arrived.19

On the morning of 18 November, Commander Whiting climbed into the cockpit of a Naval Aircraft Factory PT seaplane that was positioned on the Langley’s carriage contraption connected to the end of Little David. What he was about to attempt—the first manned catapult launch from an aircraft carrier—would not go unnoticed. An hour earlier, representatives from five different motion-picture companies had set up their cameras alongside those of the Navy as the ship was anchored in the York River. Not only had Moffett returned, but other notables from Washington also were on hand to view the event. According to the carrier’s deck log, at 1138, “T.P. A—6048 was successfully launched from the catapult with Comdr. K. Whiting as pilot.”20 Weller wrote: “Catapult attaining speed of 65 mi. per hour and seaplane up to flying speed reached end of deck. Plane drop 40 ft. then ascended, come alongside and hoisted aboard.”

However, it was not a flawless evolution. As Whiting and the PT roared down the deck, the lift on the seaplane’s wings caused the aircraft to foil the mechanism designed for releasing the pontoons from the carriages. The pilot succeeded in getting airborne, unaware, to Pennoyer’s horror, that bottom planking for both of his pontoons remained on the focs’le, still attached to the carriages.21

As Whiting flew the plane around the Langley, crewmen on deck pointed up to him to alert the pilot of the damaged pontoons. With the carrier’s crane swung out in anticipation of hoisting the PT aboard, Whiting calmly landed, pulled up under the crane hook, and latched on before water had a chance to fill the pontoons. The crane then hauled the plane out of the York River.22

With news of Whiting’s successful cat shot, Moffett would go before the House Appropriations Committee on 22 November to make the case for additional naval aviation funding. He noted that though the British were still well ahead in carrier aviation, the United States had a lead in naval aviation on ships in general—given the number of catapults being installed on battleships and cruisers. Moffett boasted the program had suffered no accidents or casualties. Given what was being recorded in Weller’s diary and on film, the bureau chief was being less than truthful.23

The season’s first snowfall canceled flight operations during the last week of November, and following the Thanksgiving holiday, Doyle wrote to Moffett about his concerns that continuing operations in northern climes in January and February could result in loss of aircraft. As a result, the Langley headed south in the new year to continue testing off Pensacola during the remaining winter and early spring months. She also made a cameo appearance following the Navy’s first Fleet Problem, off Panama in April 1923.

The Langley returned to Norfolk, but Weller’s reunion with his family would be short-lived. Moffett decided to deploy the carrier to Washington, D.C., in early June, when the Shriners national convention was being held there. The goal was to impress the “Shriner-in-Chief”—President Warren G. Harding, members of his cabinet, and Congress with ship tours and flight demonstrations. Given the great public response, over the ensuing months, Weller would fill diary entries with observations about New York, Newport, Portland, Boston, and Marblehead.

The Langley returned to the Caribbean in time to join the aggressor Black Fleet in Fleet Problem III/Grand Joint Exercise Number 2—a test of the Army’s and Navy’s abilities to defend the Panama Canal Zone. Black Fleet commander Vice Admiral Newton A. McCully secretly gathered his force at Panama’s Chiriquí Lagoon, close to the Costa Rican border. With the Fleet Problem/Grand Joint Exercise set to start on 14 February 1924, the Langley was ready to make her mark.24

However, before Doyle could get his two Douglas DT-2 seaplanes airborne, his carrier was subjected to a preemptive attack. Two Army planes launched from the Canal Zone overflew McCully’s fleet and pelted the Langley’s flying deck with ripe Costa Rican tomatoes. Weller captured in his diary the mock struggle for the security of the canal and the subsequent liberty for the fleet in the Canal Zone.

Weller’s narrative continues with Fleet Problem IV, which had the Langley supporting an amphibious operation to seize Culebra, to the east of Puerto Rico. Following a port call to Martinique, Joseph Weller’s diary ends when the Langley arrived in Pensacola in March 1924.

The Navy’s first aircraft carrier, following another extensive yard period in Norfolk, would be reassigned to the West Coast, where she would participate in numerous Fleet Problems and make critical contributions to the development of carrier air doctrine. Converted to a seaplane tender in 1937, she was sent to the Philippines. With the onset of war, she escaped from Manila but was heavily damaged by Japanese naval aircraft during a plane-ferrying mission off Java at the end of February 1942 and was sunk by an escorting U.S. destroyer.

After leaving the Langley, Weller continued to serve. The 1930 census placed him in the destroyer Osborne (DD-295), which was in Philadelphia to be decommissioned. Retiring as a chief electrician’s mate after completing 20 years of service, Joseph returned to Norfolk with Adeline and the children. There, he landed a job as an electrician at the Navy Yard.25

Weller returned to active duty in June 1941. The 1943 Navy Commissioned and Warrant Officers Registry identified him as a chief electrician warrant officer. A year later, it listed him as a lieutenant (junior grade), the rank he would retain on the Navy’s retired list following his release from active duty in December 1945. Joseph and Adeline would retire to Florida, where he passed away in 1975. Adeline lived on for eight more years. Their final resting place is the Riverside Memorial Park in Norfolk.

1. RADM J. R. Tate, USN (Ret.), “Covered Wagon Days,” Naval Aviation News, December 1970, 32; USS Langley deck log excerpts, Langley folder, National Naval Aviation Museum (hereafter NNAM).

2. Joseph Weller diary, NNAM.

3. Ohio Roster of Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines who served in World War I, 1917-1918, 2,168; Electrical Class Completion List, Our Navy, April 1915, 33; Ancestry.com searches on Joseph Weller and Adeline McGrath.

4. Langley chronology, Langley Box 1, Folder 3, Naval History and Heritage Command (hereafter NHHC); Weller diary, NNAM; Notes from Hudgins talk, Langley folder, NNAM Library; Joseph Weller obituary, Newport News Daily Press, 27 October 1975.

5. Weller diary; Notes from Hudgins talk.

6. Weller diary; Langley deck log excerpts.

7. E. T. Wooldridge, ed., The Golden Age Remembered: U.S. Naval Aviation, 1919–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 68–69.

8. Tate, “Covered Wagon Days,” 32; Weller diary.

9. Tate, 33; Wooldridge, The Golden Age Remembered, 69–70; USS Langley deck log, 26 October 1922, Langley Box 1, Folder 1, NHHC.

10. Gareth L. Pawlowski, Flattops and Fledglings: A History of Aircraft Carriers (Cranbury, NJ & London, England: A. S. Barnes & Co. and Thomas Yoseloff Ltd., 1973), 20; Weller diary.

11. Tate, “Covered Wagon Days,” 33; BuAer Newsletter, 1 November 1935, NHHC; Langley deck log, 26 October 1922; Weller diary.

12. Ryan D. Wadle, Selling Seapower: Public Relations and The U.S. Navy, 1917–1941 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 39–40, 50–54.

13. Weller diary; Langley deck log excerpts. Weller had Griffin, Daly, and Chevalier landing while the log recorded Griffin and Pride doing so.

14. Weller diary; RADM George Van Deurs, USN (Ret.), “Ken, Horse, and the Cats,” Shipmate, January–February 1983.

15. Weller diary.

16. Weller diary.

17. Weller diary.

18. Weller diary.

19. Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick. United States Naval Aviation; 1910–2010, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015) 75; Wooldridge, The Golden Age Remembered, 71; Weller diary.

20. Evans and Grossnick, United States Naval Aviation, 76.

21. Tate, “Covered Wagon Days,” 32; Langley deck log, 18 November 1922.

22. Tate, 32; Wooldridge, The Golden Age Remembered, 71.

23. William F. Trimble, Admiral William A. Moffett: Architect of Naval Aviation (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 105–6.

24. Weller diary, NNAM; Albert A. Nofi, To Train for War: The U.S. Fleet Problems, 1923–1940 (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010), 62.

25. 1930 and 1940 federal census reports, Ancestry.com.