By the time R. Buckminster Fuller received his patent in June 1954 for a “geodesic, hemispherical structure for enclosing space,” he had already formed a mutually beneficial relationship with a very important client for his new designs: the U.S. Marine Corps.

His patent—the geodesic dome—was an ingenious use of engineering to produce a complex yet strong structure out of easy-to-assemble parts. The dome, with a framework of simple materials such as aluminum alloy or paperboard, could be easily erected with little advance training. And most important, it could be done quickly.

The Korean War and the importance of mobility (and particularly air mobility) was looming large in many Marine commanders' minds. For years, the Marine Corps had sought lightweight, simply built structures that could be air-delivered to front-line troops to shelter them and their equipment; the war in Korea had only reinforced those needs. It was no surprise that after a Marine officer read about Fuller’s work building a dome for the Ford Motor Company in 1953, the Corps approached Fuller and his firm, Geodesics, for assistance. The domes seemed like a natural solution for solving the equipment problem.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

Testing with the domes began in January 1954. Marine Helicopter Squadron One (HMX-1) was pressed into testing the domes for Marine aviation, and soon it was using its helicopters to test some of Fuller's designs for domed aircraft shelters. In several instances, HRS-1 "Chickasaw" helicopters were photographed lifting their own Geodesic hangars into the sky—a demonstration of the utility of the design.

The experiments showed that a helicopter could airlift the fully assembled hangar domes to a new location, land, and then be stored inside. For a force on the move, the utility of the structures seemed ideal. One Marine colonel in his final report on the project would call them “the first basic improvement in the mobile military shelter in 2,600 years.”

Several other designs followed, including structures for housing and a 55-foot-diameter aircraft shelter that could house the transport helicopter and two smaller HO5S-1 observation helicopters; this dome was once tested on board an aircraft carrier, then picked up by a helicopter and air-delivered to Quantico at a speed of 60 knots.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archives)

Improvement or not, for it to work properly, it required the Marines assembling it to follow its inventor’s recommendations. Though built to withstand wind velocities of up to 150 miles per hour, that strength presupposed the structure was anchored to the ground. One windy night, the shelters were evidently not tied down, and they blew straight into the Potomac River, thus ending the tests on the geodesic hangars.

Though the final report recommended the immediate adoption and phasing in of the domes for aircraft shelters and other purposes, the Marine Corps ultimately elected not to pursue further development along those lines.

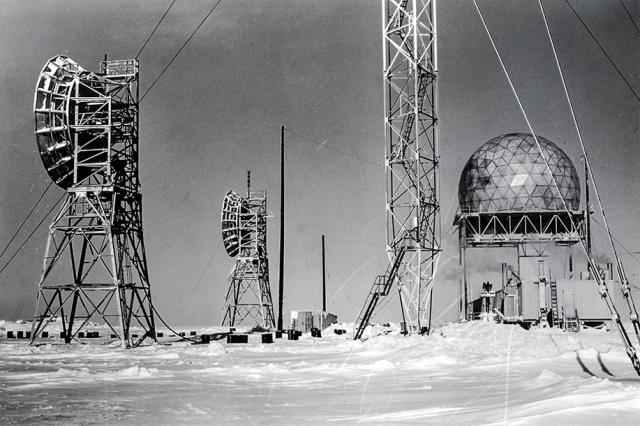

However, one design for the Department of Defense proved preeminent: an all-fiberglass construction designed for housing radar that Fuller dubbed the radome. Because they were found to naturally and easily shed ice and snow, the DOD eagerly snapped up the design for installation on the DEW line and elsewhere.

Radomes in many forms are still familiar sights at many military installations today.