Alright, everyone, today I am going to take you on a shallow dive into a topic that's tough for a lot of people to talk about for many different reasons: racial segregation. Specifically, the history of racial segregation in the Navy through World War II. It is never fun, but it is a very important part of our history, and something that we need to examine no matter how uncomfortable it can make us feel.

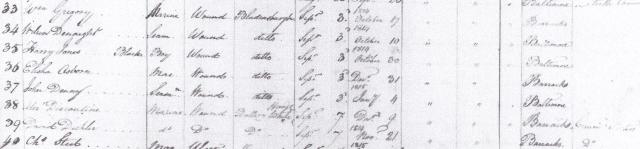

The history of black sailors in the Navy begins with the War of 1812, as the U.S. Navy was not established until after the American Revolution. At the beginning of the war the official policy forbade recruitment of black sailors, but a shortage of men forced the Navy to accept any man who was willing to serve. According to modern estimates, 15–20 percent of the Navy's force during the War of 1812 was made up of black sailors. While a number of black men did defect to the British Navy, it is important to note that many of these were enslaved men, who had been promised freedom in return for their service. One of my favorite quotes from this period comes from Commodore Joshua Barney during the Battle of Bladensburg. When President James Madison asked if his black sailors would "run on the approach of the British?" Barney replied: "No, Sir . . . they don't know how to run; they will die by their guns first." One such man was Harry Jones, who was one of the many black seamen who did not abandon his post, but rather fought valiantly, getting wounded in the process.

To my surprise, I found out that the U.S. Navy was integrated during the Civil War, unlike the U.S. Army. While federal regulations limited African American sailors to 5 percent of the enlisted force, during the war that participation grew to 20 percent, nearly double the percentage who served in the Army. There were approximately 18,000 black men and 11 women who served in the Navy during the Civil War. One important point to note, however, is how their ranking and status was dependent on whether they came on board free or formerly enslaved. Formerly enslaved men were classified as "Boys," and given lower pay and rating.

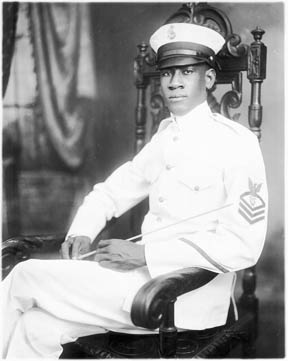

While integration on ships continued through World War I, so did the lack of equality between black and white sailors. Some African American sailors were promoted to petty officers, but none would be promoted past that rank as their white counterparts would. Because of the segregation policies of the U.S. armed forces, their participation was relegated to support roles, most commonly as mess attendants and firemen.

It is at this point in the U.S. Navy's history that it took a large step backward. After the war, African American enlistments were banned altogether, from 1919 through 1932. The only black sailors were the ones who joined before the 1919 ban, who were allowed to stay on until retirement. African Americans once again were allowed to serve on board U.S. Navy ships in 1932, but only as stewards and mess attendants.

In June 1940, the Navy had 4,007 black personnel, which represented 2.3 percent of the 170,000 service members in the Navy. All were enlisted and, with the exception of six regular-rated seamen, all were steward's mates. They were characterized in the black press as "seagoing bellhops." Within a month on the attack on Pearl Harbor, the number of African Americans in the Navy increased to 5,026, but they still were restricted to working as steward's mates. An exception to this was the Navy bandmaster Alton Augustus Adams, who was recalled to active duty along with eight other black musicians, creating the Navy's first racially segregated ensemble.

The USS Mason (DE-529) was the only Navy vessel during World War II to have an entirely black crew who were not cooks or waiters. The Mason served in convoys, escorting support ships to England. In one incident, the crew quickly welded the cracks in their ship's hull so they could continue their duties. They unfortunately were not fully recognized until 1995, when 11 of the surviving members were given letters of commendation by Navy Secretary John Dalton.

The Navy did not allow women of color to serve until 25 January 1945. The first black woman sworn into the Navy was Phyllis Mae Dailey, a nurse and Columbia University student. She was the first of only four black women to serve in the Navy during World War II.

On paper, the history of Navy segregation ended on 27 February 1946, when Circular Order 48-46 officially desegregated the service. A major catalyst for this order was the Port Chicago disaster of 17 July 1944, and the ensuing mutiny convictions of 50 black sailors.

This is merely an overview of the history of racial segregation in the Navy until the end of World War II. It by no means is the definitive explanation of the injustices wrought upon black people during their time serving our country, and it should be noted that after the 1946 Circular Order, segregation and racism did not just vanish. But I still wanted to share this, because it is something I think we need to remember, and something from which we can still learn. The most amazing and admirable thing I took away from this research is that, despite the discrimination they had to know they would face, African Americans still chose to serve and be integral parts of a system that did not always appreciate them or treat them equally. So, to all those who served in conditions unworthy of their sacrifice, thank you. May we never forget what you went through, so we can always strive to be better.