In 1890, Japanese diplomat and political theorist Inagaki Manjiro, the Cambridge-educated son of a samurai, wrote, “Without doubt the Pacific will in the coming century be the platform of commercial and political enterprise.” Four years later, a war broke out between Inagaki’s Japan and Imperial China—a conflict the results of which still echo in the Indo-Pacific today.

The prescient Inagaki also is credited with being first to use the term “the Pacific Age.” If we now find ourselves living in this Pacific Age, the shape it has taken was molded early on by that First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95—a war brief in duration but far-reaching in its reverberating impact. To understand the posture of an increasingly navalist People’s Republic of China today, one should start with the crushing defeat China’s navy suffered back then.

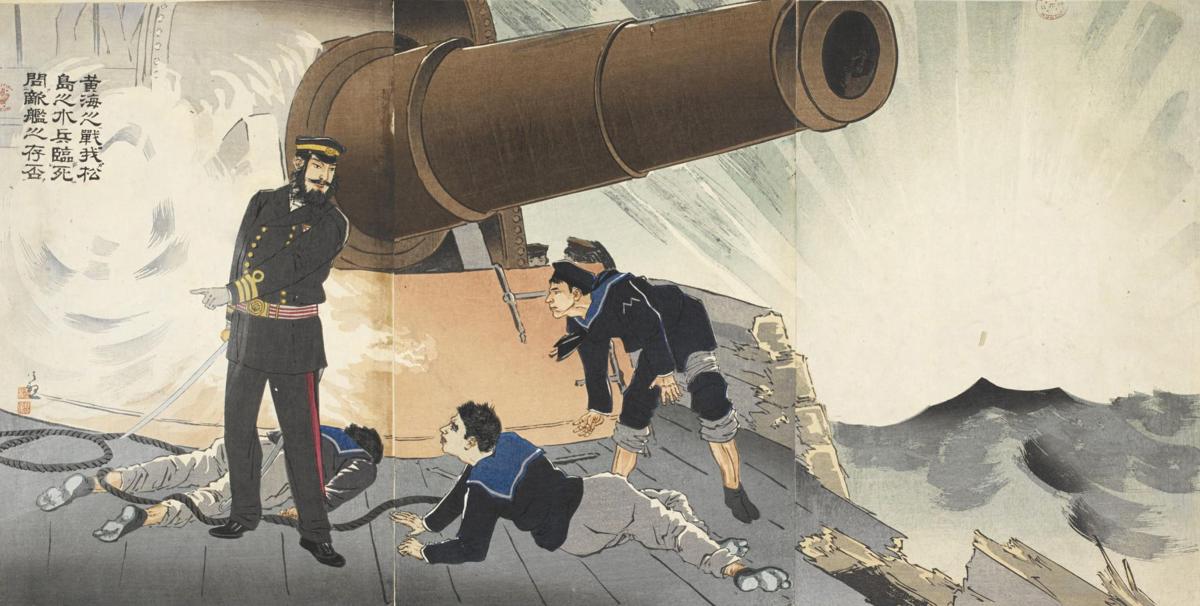

In this issue, Andrew Blackley connects the dots between Pacific geopolitics then and now. In describing those events that attended to the birth of an era, he contrasts two rival Asian fleets that both had embraced modern warships but otherwise were vastly different culturally. The war in general, and China’s humiliating naval loss at the 1894 Battle of the Yalu River in particular, inflicted on the Chinese psyche a wound that never quite healed. The memory of it lives on. It serves as a “never again” call to arms for an emergent 21st-century Chinese naval presence—and it also serves as an example of how the sting of defeat can become a consuming obsession for the defeated.

The calendar of historical anniversaries provides us with another such example of fixation over a failure: Sixty years ago this April, a young, dynamic new U.S. President was at the helm. Charismatic, telegenic, he and the First Lady were the shining symbols of a new decade and a new generation in charge. But barely three months into his presidency, John F. Kennedy found himself embroiled in the fiasco that was the bungled Bay of Pigs operation.

The new commander-in-chief had inherited this CIA/Pentagon plan to bankroll, train, and transport expatriate Cubans to liberate their homeland from the communist overlordship of Fidel Castro. JFK could have (a) opted not to go through with this holdover scheme, (b) gone ahead with it with all the necessary U.S. air and naval support the landing would need to succeed, or (c) tried to have it both ways, offending neither hawks nor doves, and go in halfheartedly and hope for the best. Unfortunately, he chose (c), and the whole thing blew up in his face.

As Norman Friedman notes in this issue’s 60th-anniversary Bay of Pigs retrospective, JFK was obsessed with Castro from then on. The perilous brinksmanship that would follow in the wake of the Bay of Pigs came close to having apocalyptic consequences the following year. While Dr. Friedman provides the big-picture overview of those tense times, with an emphasis on naval strategic implications, his analysis is augmented by a gripping, you-are-there account of the Bay of Pigs landing itself, courtesy of a young U.S. Navy sailor whose firsthand recollections are preserved in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Oral History Collection.

Elsewhere in this issue, former Proceedings Author of the Year Graham Scarbro and Desperate Sunset author Mike Yeo serve up a pair of fascinating sea stories from the Pacific war—one of which includes freshly unearthed details that correct the historical record, thanks to the communicative synergy of social media. A remarkable and thoroughly unique Marine hero of the Vietnam War is remembered in these pages as well—and for the Age of Sail–inclined, frequent “Armaments & Innovations” contributor Philip K. Allan makes his feature-article debut with a look at “The Duke of Wellington’s Navy.” What, you ask? Isn’t that like saying “Nelson’s Army”? Intrigued? Well . . . read on!

Eric Mills

Editor-in-Chief