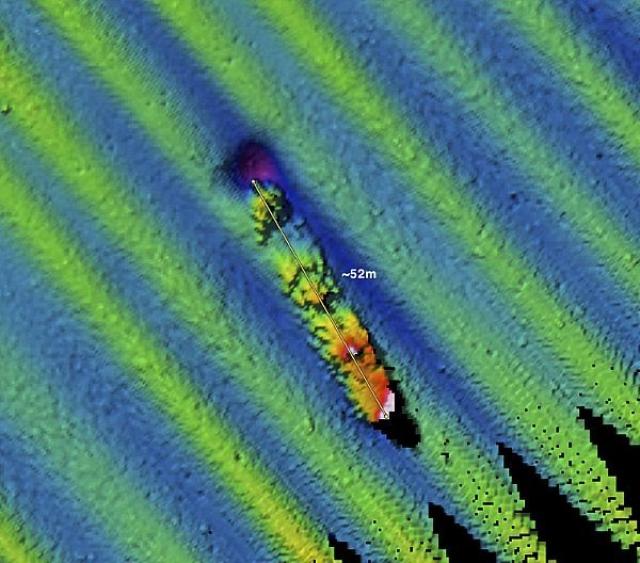

The discovery of a deteriorating hulk of a ship in just 189 feet of water, 27 miles outside of San Francisco’s Golden Gate, resolved the question of what had happened and where lay the wreck of the USS Conestoga (AT-54), one of only 18 U.S. Navy ships that disappeared, never to be seen again in the years before World War II.

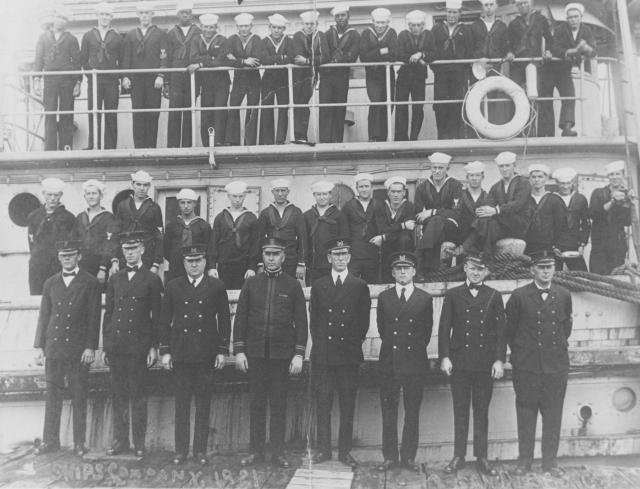

On 25 March 1921, the Conestoga had departed Mare Island Navy Yard with orders to proceed to Pearl Harbor. From there, she would steam to American Samoa to take up duties as station ship in that distant South Pacific outpost. Passing out of the Golden Gate that afternoon, the tug and 56 men never reached Pearl Harbor. A garbled radio message, a battered, drifting lifeboat discovered by a passing steamer off Mexico’s coast, and a single life vest with the lost tug’s name found cast up on a California beach were the only clues. Two extensive searches by sea and air failed to find any trace of the Conestoga through the summer of 1921.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

The survey that ultimately discovered the wreck was part of a systematic scientific quest to learn more about what lies on the seabed and in the waters of Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary off the Central California Coast. The sanctuary is believed to contain the wrecks of some 400 lost ships. Since 2014, the maritime heritage program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries has worked to locate some of these ships, based on both archival records and sonar targets revealed by seabed mapping by NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey.

As an archaeologist who works in the depths of the sea, I have encountered many lost ships. Not all of them have names, at least that we can discern. Some sailed so far in the past that the languages their sailors spoke, the cultures they belonged to, and the states to which they pledged their allegiance are long gone. Even the study of wrecks of more recent vintage does not always reveal a name. And yet we are certain, with some, that we likely have resolved mysteries and answered questions long forgotten.

What will ultimately come to pass, as the 90 percent of the oceans that remain unexplored are at last surveyed, is that while in many cases unanswerable questions will be posed by shipwreck discoveries, many other unsolved mysteries will be answered. Among them may be the final resting places of the U.S. Navy ships and submarines that went missing and that remain undiscovered. The first accounting of lost Navy ships appears to be a report to Congress on 14 March 1850, in which 7 of 29 losses were ships “never heard of’ after sailing.

(U.S. Navy photo courtesy of NOAA)

In July 1934, Constance Lathrop, Navy Department librarian, listed the 19 “vanished ships” of the U.S. Navy in Proceedings. “From time to time in the history of our Navy one of its ships has vanished at sea without trace. Impenetrable mystery shrouds their disappearance, as unfathomable in this day of steam, radio and well-charted sea lanes as in the day of ‘oak and hemp’ when the only means of communication lay in mail left at a port of call, or in one ship speaking another at sea.”

In answer to the question of which ships were “missing,” Lieutenant Commander Arnold S. Lott, head of the U.S. Navy Office of Information (CHINFO) Research Section (and a noted historian and later an editor with the Naval Institute) wrote a letter to the editors of All Hands in March 1958 listing losses that he drew from Lathrop’s article and CHINFO’s files. Lott’s roll of the lost begins in 1780 (with the Continental Navy sloop Saratoga) and ends in 1921. To that, one can add fleet boats that vanished on patrol. In all, the final locations are for now unknown for 15 out of the 52 U.S. submarines lost in World War II. Since the publication of Lott’s list, two of the unaccounted-for pre-World War II losses, the screw steamer Nina and the Conestoga, have been discovered.

Click here to read Dr. Delgado’s August 2016 Naval History article that features capsule histories of the U.S. Navy’s remaining lost ships.