The Navy was not the first military branch to establish an auxiliary corps consisting chiefly of women. In 1941, Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts presented a bill to congress to establish WAAC, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, and after opposition, the bill passed a year later in 1942. This bill provided that women would serve with the Army rather than in it, meaning that the women would not receive the same benefits of their male counterparts despite doing the same work.

In 1941 the Navy was not interested in adding women to its ranks of personnel. After a year of prodding from Congress, however, the Navy made an about-face and began looking into how to incorporate women. While some in the Navy wanted something similar to WAAC, where women would serve with but not in the Navy, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox found this idea to be unacceptable. Instead of using the existing model, the Navy asked women educators of the nation to form the Women's Advisory Council, which would work with the them to formulate an administration for a women's reserve within the Navy itself.

The Women's Advisory Council was led by Elizabeth Reynard, who also acted as special assistant to Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, Chief of Naval Personnel. Once the council was established, their first order of business was to choose the woman who would lead this new organization once it was established, as they all knew the success of the program would rest on her shoulders. After much deliberation, the council recommended Mildred H. McAfee, president of Wellesley College, as they believed her to possess the proven managerial skills, command respect, have the ability to get along with others, and—possibly most important—through her respected reputation provide credibility to the idea of women serving in the Navy. Once McAfee was signed on, Reynard was then tasked with choosing a name:

I realized there were two letters that had to be in it: W for women and V for volunteer, because the Navy wants to make it clear that this is a voluntary service and not a drafted service. So, I played with those two letters and the idea of the sea and finally came up with Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service—WAVES. I figured the word Emergency would comfort the older admirals because it implies that we're only a temporary crisis and won't be around for keeps.

Despite the advice of the women's council, on 25 May 1942 the Senate Naval Affairs Committee recommended to President Roosevelt that the creation of a women's reserve should parallel the original WAAC legislation. While Roosevelt believed the choice sound, Knox refused to budge on allowing women to serve in the Navy as reserves. Two women from the council—Virginia C. Gildersleeve and Harriet Elliot—took it upon themselves to write Eleanor Roosevelt, who then showed the president the letters. Seeing his chance, Knox asked the president to reconsider, and on 16 June 1942, Knox confirmed the president gave him authority to proceed with a women's reserve.

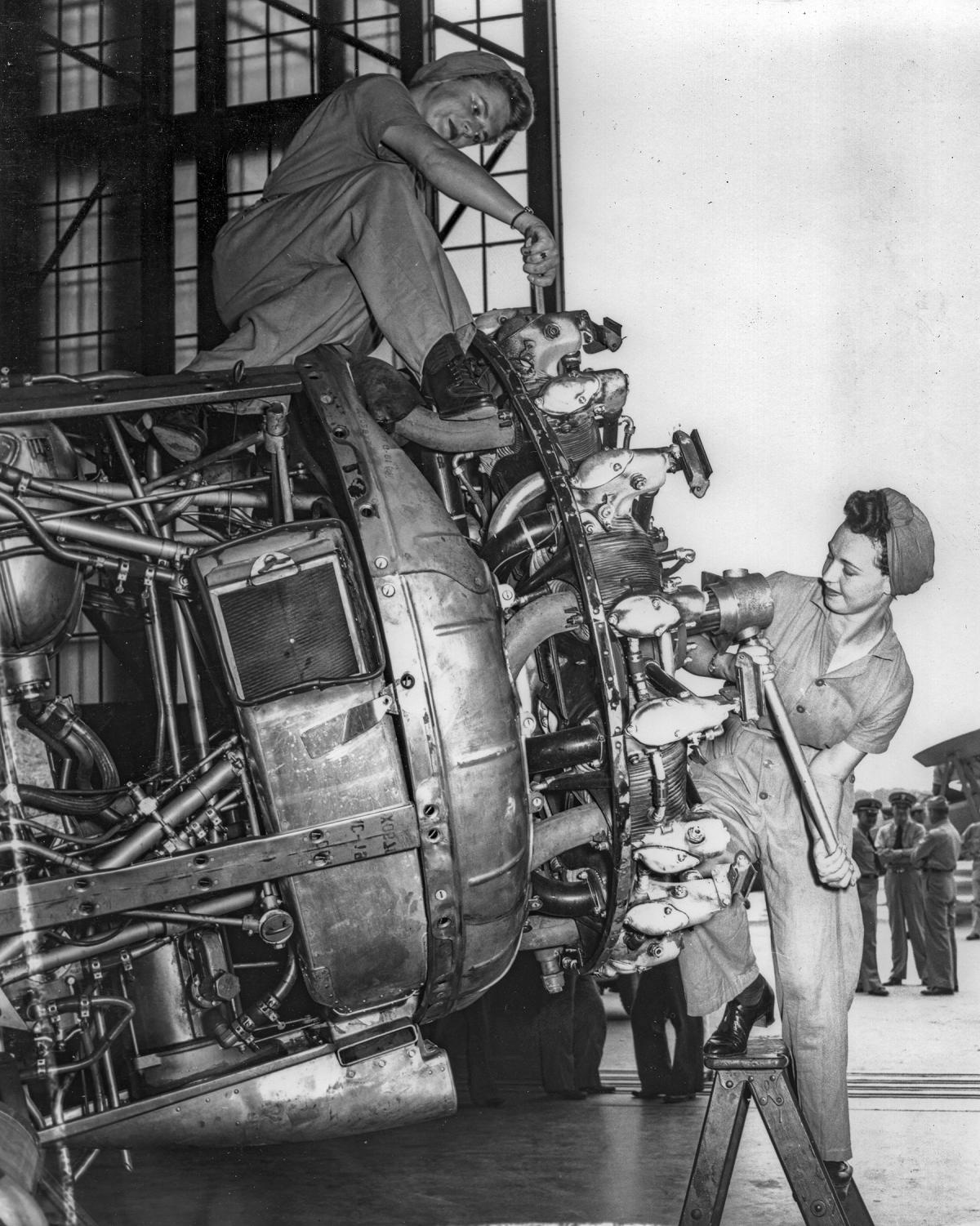

The president's approval gained, Knox then began to work with the Senate Naval Affairs Committee to get a bill passed allowing for women to serve in the Navy reserve. The bill was sent to President Roosevelt on 30 July 1942, and it was signed as Public Law 689. According to this law, women could now serve in the Navy as an officer or at an enlisted level, with rank or rate consistent with the regular Navy. However, these volunteers could only serve for the duration of the war plus six months, and only in the continental United States. Most of the lawmakers passing this law only agreed because it would free officers and men for duty at sea, not because of a desire for greater equality between the sexes. This is clear both by the clause of how long women could serve, as well as ones prohibiting women from boarding naval ships and combat aircraft, and that they had no command authority outside of the women's branch.

As with any move toward progress, even small steps can make big changes, and McAfee had the experience to create lasting waves with the small steps afforded to her. After being commissioned as a lieutenant commander on 3 August 1942—thereby becoming the first women in the U.S. Naval Reserve—she set to work establishing the WAVES. No planning had been done in preparation for the Women's Reserve, and McAfee was simply told to "run" the branch. Recognizing that she had a duty to create a sound organization, McAfee turned to Joy Bright Hancock, a Navy Yeoman (F) during the First World War, for guidance. McAfee had Hancock examine the procedures employed by the Women's Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force, which already had a complement of 6,000 members, and many of Hancock's findings there were utilized by the WAVES.

McAfee then got to work selecting officers to work in the WAVES, and by September 1942, 108 women were commissioned as officers. Four of these would go on to be directors of the WAVES and the director of SPARS (U.S. Coast Guard Women's Reserve). Many of these women were drawn to the WAVES by the original Women's Advisory Council and by McAfee's own reputation. The final piece of the foundation of WAVES occurred on 16 September 1942, which connected the workings of the Women's Reserve to the Bureau of Personnel, ensuring that the Navy's established traditions, training, and operating methods would be incorporated in the WAVES as well.

While researching how the WAVES were formed, the aspect of the process that struck me most was how carefully the women working toward its creation planned every step. They could clearly see that if they did not present their organization in the right way, laws like those establishing WAAC would keep their work in the military from being fully recognized (WAAC would eventually be refashioned into WAC, which provided similar military status as the WAVES). Though I wish these women did not have to navigate a tightrope of clauses and addendums to ensure the recognition of women's service, my gratitude toward their work is undeniable. It is because of these women that thousands of others found a way out of the home and into the workplace and many discovered their own ambitions while fulfilling a patriotic duty. They learned new skills no one at the time believed they could or should do and set a precedent that could not be denied: women can work and do work well. To Mildred H. McAfee, Elizabeth Reynard, Eleanor Roosevelt, and all the other women who laid the foundation: Thank you for taking those steps and for making those WAVES.