In the harbor of Weihai, China, there is docked an unusual museum ship, the Dingyuan, built in 2005 as a re-creation of the flagship of the Qing Dynasty’s Beiyang (Northern) Fleet. She is a popular tourist destination, resplendent in her livery of white and black and flying the yellow Imperial Dragon ensign.

However, unlike the typical museum ship that preserves an actual historic vessel and commemorates some past naval glory, the Dingyuan is a faithful replica of a warship that had an ignominious career—defeated in battle and eventually meeting destruction at the hands of her own crew. Why would China go to the great expense of creating a monument to its defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95)?

The answer is that the ship is not only a memorial to the brave sailors who fought and died in what the Chinese refer to as the “War of Jiawu.” It has a political purpose as well: reminding the Chinese people of the inability of the Qing Dynasty to adapt to the modern world. Reminding them of when China depended on foreign nations to provide it with modern weapons and expertise, as those same nations intervened in Chinese affairs with impunity. Reminding them of the consequences of failing to resist Japanese aggression.

Jiang Peiqi, who headed the re-creation effort, said, “The Dingyuan is closely tied with the Chinese history of resisting foreign invasion. To re-exhibit China’s ‘first’ warship of the time will alert later generations not to forget national humiliation.”1

China’s defeat in the War of Jiawu led to decades of civil strife, warfare, and untold suffering. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is committed now to becoming a great maritime power, in part to prevent another such humiliation. The United States, as the world’s dominant naval power, sees this effort as a challenge to the maritime security of the region. It is worthwhile, then, to examine the naval aspects of a war that has had such a profound impact on the history of the Far East—and consider what insights it might offer about future naval conflict in the region.

Rivals for Control over Korea

In 1860, neither China nor Japan had navies capable of defending their nations from the seaborne domination of the Western powers. By 1894, both had succeeded in establishing powerful fleets with modern warships, but because of cultural and historical factors unique to each, where Japan succeeded in creating a national navy under a unified command, China chose to keep its naval forces in independent, uncoordinated commands under the control of provincial officials.

China and Japan had long struggled for dominance over the Kingdom of Korea. China considered Korea a vassal state and therefore part of its empire. Japan saw the Korean Peninsula as a threat, as a potential jumping-off point for a continental invader, and considered control of Korea to be a strategic necessity. Tensions escalated as China and Japan sought to influence Korea’s internal affairs by supporting one of the competing factions that fought to control the kingdom. In July 1894, after both sides had dispatched troops to support the faction they favored, Japan issued an ultimatum to China to withdraw its troops or face war. On 25 July, after the deadline had passed without response, Japanese naval forces intercepted and sank a hired British ship loaded with Chinese reinforcements who had refused the order to surrender, resulting in a large loss of life. Subsequently, war was declared on 1 August 1894.

China’s Beiyang Fleet, built in the 1880s, had been created by Li Hongzhang, the powerful viceroy of Zhili Province, to provide a modern naval force for his northern domains. He now found himself defending Chinese interests and facing a powerful enemy without help from the rest of the Chinese Empire. The ships of the Beiyang Fleet were equipped with rams and large, slow-firing, breech-loading guns mounted to provide strong bow fire, but they had no quick-firing (QF) medium-caliber guns. The flagship Dingyuan and her sister ship Zhenyuan, built in Germany in 1884, were armed with four Krupp 12-inch (30.5-cm) guns and protected by a citadel of 14-inch-thick armor. They were considered to be superior to any ship in the Imperial Japanese Navy.2 (See “A Global Phenomenon,” June 2020, p. 19.) These ironclads may have been state-of-the-art in the 1880s, but by 1894 they were approaching obsolescence, and the central Chinese government, while possessing great resources, failed to recognize the need to modernize its naval forces.3

The Beiyang Fleet’s commander was Admiral Ding Ruchang, a Manchu cavalry general with no naval experience. Ding’s subordinate commanders were southerners trained at the Fuzhou Naval Academy and had served continuously on these ships since their commissioning. The pairing of a Manchu “admiral” with southern officers commanding a fleet manned by northern seamen was reflective of the typical Qing policy of using ethnic and regional differences to prevent the creation of power centers disloyal to the throne. It did little, however, to foster unit cohesion and cooperation, to say nothing of a national spirit.

‘Tactical Orders . . . Found Wanting’

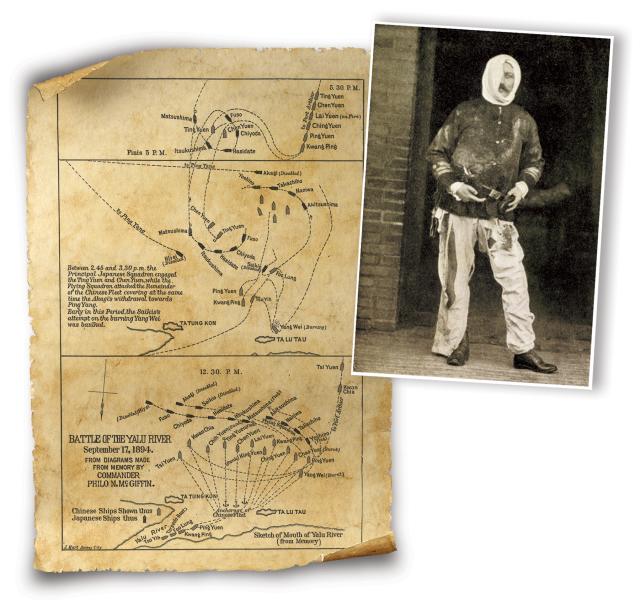

With tensions rising, Li recruited Western advisers to act as co-commanders and gunnery experts on the two ironclads.4 These included Major Constantin von Hanneken, a Prussian artillery expert and close confidant of Li, to act as the co-admiral; William F. Tyler, a Royal Navy Reserve sub-lieutenant, employed by the Imperial Customs Service as co-commander of the Ting Yuen; and Philo N. McGiffin, a navigation instructor at the Chinese Naval College and U.S. Naval Academy graduate (class of 1884), as co-commander of the Chen Yuen. On joining the fleet, they found that the ammunition supply for the guns of the ironclads was very low and of poor quality. Only three of the forged shells originally supplied by Krupp still existed.5 Fresh supplies were ordered from the Tientsin Arsenal. Despite the urgent need, the manager, the son-in-law of Li Hongzhang, would supply only the standard allotment of cheap, locally made shells, which were too few in number for combat and of inferior quality.6

The fleet’s tactical orders and signal system also were reviewed and found wanting. Because there was no time to make up for years of neglect in training and practice, a set of standard instructions was issued, stating that “in action sister-ships, or each pair . . . shall remain together if possible and mutually support each other in attack and defense. . . The fundamental tactics will be always to keep bows on to the enemy . . . all ships shall follow as far as possible the motions of the Admiral.”7 The Chinese fleet never deviated from these instructions.

The Japanese Combined Fleet, under the command of Admiral Ito Sukeyuki, consisted of eight protected cruisers and was divided into the Flying Squadron and the Principal Squadron, based on the speed of the ships. The Japanese ships, while lightly armored, were faster, more modern, and together carried more than 50 QF guns, all located in broadside batteries.8 Ito and his subordinates were professional naval commanders with many years of experience at sea. They would spend the early summer of 1894 training and exercising their fleet to follow signal commands and maintain tight tactical order—practice that would soon pay off.

Clash on the Yalu

The Qing government still harbored hopes of making peace before real hostilities started and did not want to provoke the Japanese. The Chinese fleet therefore was forbidden to mount offensive operations and largely was confined to defensive patrols.9 The Japanese, however, had no intention of making peace, and after landing additional troops at Inchon, the Combined Fleet was ordered to find and engage the Chinese, who were reported to be at the Yalu estuary in the Yellow Sea. The two fleets met there on the morning of 17 September 1894.

The Chinese fleet was at anchor, having escorted troop transports the previous day, and at around 0900 spotted the Japanese Combined Fleet on the horizon. The Chinese moved out to sea in two columns led by the two ironclads, followed by eight cruisers in paired sections, a formation recommended by Ding’s advisers. As the two fleets closed, however, the Chinese fleet spread out into its accustomed line-abreast formation, which assumed the shape of a sagging crescent, with the most powerful ships out in front at the center and the weaker ships on the wings.10 This would prove to be a very poor tactical choice, as the weakest ships would be located where they would be most vulnerable to attack.

The Japanese squadrons advanced at speed in line-ahead formation across the Chinese front, while still beyond the range of the 12-inch guns, to attack the right wing. The Dingyuan opened fire at the extreme range of 6,000 yards, but without telescopic sights and having only rudimentary range-finding, the shots fell well short. The order to fire was given at a moment when Admiral Ding and his Western advisers were standing together on a port wing of the Dingyuan’s flying bridge, which was located immediately in front of the big Krupp guns. The resulting muzzle blast sent the men flying, leaving them badly injured and out of the battle for some time.11 Not long thereafter the ship’s foretop mast was knocked away, leaving her unable to signal orders to the rest of the fleet, which would now have to fall back on its basic instructions to “follow the Admiral” and fight in pairs. Right from the beginning, the Chinese fleet was fighting without leadership.

The opponents soon were locked in a circling fight, with the Japanese using their superior speed to choose the range and stay ahead of the bow guns of the Chinese warships. The Japanese QF guns, while unable to penetrate the heavy armor of the ironclads, made a shambles of their unarmored superstructures and started serious fires. The Chinese fought bravely, but without any tactical order other than the directive to maintain supporting pairs, they were at the mercy of the Japanese squadrons, which maintained excellent order throughout the battle. The smaller Chinese ships were singled out for destruction by the Flying Squadron while the Principal Squadron concentrated on the Dingyuan and her sister, circling them completely at least three times and saturating them with rapid fire.

By dusk, four of the Chinese cruisers had been sunk while two others had fled the battle early in the fight. The Japanese also had suffered some casualties, but no ship losses. Both sides had nearly depleted their ammunition supplies after five hours of fighting. Under the cover of darkness, the two battered Chinese battleships and two badly damaged cruisers escaped to Port Arthur. Admiral Ito chose not to pursue them for fear of torpedo boat attack.12 The battle was over.

The Agony of Defeat

Ashore, the Chinese Army had suffered a serious defeat at P’yongyang on 16 September and was in full retreat. The Japanese Army soon crossed the Yalu and began its advance on Port Arthur. After effecting repairs, the Beiyang Fleet regrouped and headed for its heavily fortified base at Weihai. Admiral Ding, not willing to risk his remaining ships, sought refuge behind the guns of the harbor, ceding all sea control to the Japanese. Port Arthur soon fell to the Japanese Army, and the Japanese fleet moved on Weihai in January 1895, establishing a close blockade.

With the Chinese fleet bottled up, the Combined Fleet now could support the army’s operations without hindrance. Troops were landed 35 miles away; after a forced march, they captured the coastal batteries on the hills above Weihai from the rear and turned their heavy guns on the harbor. Japanese torpedo boats slipped past the harbor defenses in the dead of night and attacked the Chinese ships at anchor. The Dingyuan was hit and grounded, and she later was destroyed with heavy explosives by her crew. Surrounded on all sides and facing a mutiny, Admiral Ding agreed to surrender the base and his fleet on 12 February 1895. Ding and his senior officers committed suicide rather than face dishonor and the retribution that would fall on their families as a consequence of their surrender.

After the capture of Weihai, the Japanese Army threatened to advance on Beijing, so the Qing government quickly sued for peace. The resulting Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed by Li Hongzhang in April 1895, recognized the independence of Korea, ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan, and paid a huge indemnity—one that Japan would use to build an even greater battle fleet. Li was blamed for the debacle by the Qing government and stripped of his honors, but in reality, he was a victim of factors beyond his control. To this day, Li Hongzhang is still excoriated in the PRC histories of the era as a traitor to the Chinese people.

The defeat cost China its most effective naval force. The Qing and subsequent governments no longer had the resources to build a strong national navy and, with but a few warships available, were unable to resist new seaborne incursions, first during the Boxer Rebellion, and later in the Second Sino-Japanese War. When Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communists took control of the mainland in 1949, they captured large quantities of military equipment from the Nationalists but no warships. During the Korean War, U.S. and allied naval forces had total sea control, allowing them to insert or remove troops by sea and conduct naval operations at will, as the Japanese had done 55 years earlier. The 1950 Inchon Landing was a dramatic demonstration of sea power that led to the defeat of the North Korean invasion of South Korea. When U.N. forces crossed the 38th Parallel in October 1950, China decided to intervene in the Korean War, with fateful results. With the U.S. Seventh Fleet in the Taiwan Strait, Mao Zedong’s plans for the invasion of Taiwan were shelved, and the fulfillment of the Chinese Revolution would have to wait for another day.

It remains an objective looming over the region.13

Bitter Lessons Not Lost

The Qing government thought that by purchasing technology and expertise from Western sources, it could protect itself from foreign aggression without having to make the major cultural changes needed to fully use that technology. It failed to recognize that an aggressive neighbor also could acquire the same technology and successfully adopt the industrial, educational, and bureaucratic infrastructure needed to put it to effective use.

Qing officialdom too often put personal interests ahead of national purpose. Training and fleet maneuvers were curtailed because the money required for such could be pocketed instead. The same was true for supplies and proper ammunition. The Beiyang Fleet had been assembled at great initial cost, but no further investment was made to acquire more modern ships in an era when naval technology was changing rapidly. China under the Qing government had no grasp of the concept of sea power. The Beiyang Fleet was a brave front, useful for coastal defense when diplomacy failed.

The lessons from the First Sino-Japanese War were as obvious then are they are now: Victory at sea will go to the navy that possesses a highly professional officer corps, sailors imbued with national spirit, modern ships equipped with the latest technology, and a fleet organized, trained, and exercised to fight and win. These lessons are not lost on the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), which has expanded into the biggest navy in Asia, and which is now building a highly advanced blue-water fleet aimed squarely at regional and even global dominance.14

Lingering Effects of ‘National Shame’

China believes itself to be both a victim of past aggressions by foreign powers and of historical forces within that ignored the importance of sea power for centuries, forcing it now to play catch-up and put old wrongs to right.15 The influential commentator and historian Liu Yazhou, in an article titled “National Shame,” has described the War of Jiawu as “not merely a naval defeat or defeat of the army but a defeat of the nation” and, by extension, its culture.16 While Japan succeeded in embracing Western technology and created a national consciousness that animated its people, imperial China failed to do so. Thwarted by conservative, reactionary forces, its attempt at modernization was a veneer that was unable to resist foreign aggression.

The result was “a defeat most miserabl[e] in China’s history.”17 The humiliation of the loss “roused the collective consciousness of [the] Chinese people,” leading to the overthrow of the Qing in 1911 and the eventual rise of the Chinese Communist Party, which for Liu was “the turning point of Chinese history.”18 According to Liu, it is the party that has restored the spirit and faith of the Chinese nation and is leading China out from under the shadow of the War of Jiawu, and only the Communist regime and its military can prevent the repeat of such a catastrophe and restore China to its rightful place in the world.19

In a 2015 white paper, the PRC sets out its future strategic policy for “active defense in the new situation” in pursuit of President Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream of achieving the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”20 Calling the present “a new historical starting point,” it makes preparations for “maritime military struggle” a basic point of the new strategy. To this end, China will abandon “the traditional mentality that land outweighs sea” by shifting from offshore defense to “open seas protection.” This will be accomplished by enhancing the capabilities of the PLAN for “strategic deterrence and counterattack, maritime maneuvers, joint operations at sea, comprehensive defense and comprehensive support.”21

This new strategic outlook, enmeshed as it is with the burden of history, has potentially grave implications for the U.S. Navy. A humiliation at sea of China’s as-yet untested navy might lead its people to wonder if little has changed since the Qing Dynasty. No Chinese leader wants to be accused of being another Li Hongzhang, and a military reversal can look like an existential threat to an authoritarian regime.22 The PLAN will be under tremendous pressure to emerge victorious, regardless of cost, if a major confrontation, whether along the coasts of Korea, in the Taiwan Strait, or in the South China Sea, escalates into actual fighting.

In that event, the question becomes: How far will each side be willing to go in the pursuit of victory?

1. “Warship Chugs Back into Weihai,” China Daily, 29 August, 2005, www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-8835170.html.

2. Hilary A. Herbert, “The Fight off the Yalu River,” The North American Review 159 no. 456 (November 1894): 524–25. Ting Yuen and Chen Yuen, are, respectively, the Wade-Giles form of the names of the ships as they appeared in contemporary accounts of the battle.

3. Richard N. J. Wright, The Chinese Steam Navy, 1862–1945 (London: Chatham, 2001), 83, 99.

4. W. F. Tyler, Pulling Strings in China (London: Constable and Co., 1929), 38; John L. Rawlinson, China’s Struggle for Naval Development, 1839–1895 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 177.

5. Tyler, Pulling Strings, 54.

6. Tyler, Pulling Strings, 40.

7. ENS Frank Marble, USN, “The Battle of the Yalu,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 21 no. 3 (1895): 518. Marble quotes Hanneken’s “Report to Li Hung Chang.”

8. Herbert, “Fight off the Yalu,” 526.

9. Wright, Chinese Steam Navy, 89.

10. “The Chinese Navy—Battle of the Yalu,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, October 1895, 466.

11. Tyler, Pulling Strings, 50.

12. Inouye Jukichi, The Japan-China War: The Naval Battle of Haiyang (Yokohama: Kelly and Walsh, 1895), 8.

13. Dee Wu, “An Interview with Bernard Cole—China’s Evolving Military Strategy Against Taiwan,” National Bureau of Asian Research, 4 June 2018, www.nbr.org/research/activity.aspx?id=875.

14. James R. Holmes, “Fleet Design with Chinese Characteristics,” written testimony, Naval War College, 15 February 2018, 3, www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Holmes_Written%20Testimony.pdf; CAPT James Fanell, USN (Ret.), “China’s Global Naval Strategy and Expanding Force Structure: Pathway to Hegemony,” testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, 17 May 2018, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IG/IG00/20180517/108298/HHRG-115-IG00-Wstate-FanellJ-20180517.pdf.

15. Liza Tobin, “Underway—Beijing’s Strategy to Build China into a Maritime Great Power,” Naval War College Review 71 no. 2 (Spring 2018): 20.

16. LT GEN Liu Yazhou, People’s Liberation Army Air Force (Ret.), “National Shame—On China’s Defeat in the War of 1894,” Journal of East-West Thought Special Edition, Guodi Sun, transl., September 2015, 55.

17. Liu, “National Shame,” 64.

18. Liu, “National Shame,” 70.

19. Liu, “National Shame,” 71.

20. “China’s Military Strategy,” State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, May 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/05/26/document-chinas-military-strategy.

21. “China’s Military Strategy.”

22. Liu, “National Shame,” 71.