Prohibition formally began just after the stroke of midnight on the morning of 17 January 1920, when the proscriptions of the Volstead Act became effective. By the summer of 1921, newspapers had begun to report mysterious, unlighted vessels hovering off the coast. These sightings, of course, heralded the formation of “rum row.”

Rum row consisted of several clusters of vessels anchored off population centers such as New York, Boston, and Atlantic City, New Jersey. There the vessels would wait in safety, outside U.S. waters, for contact boats from shore to run out and purchase several hundred cases of alcohol at a time. It was a great setup, with all the legal risk on the boats bringing the liquor into the United States.

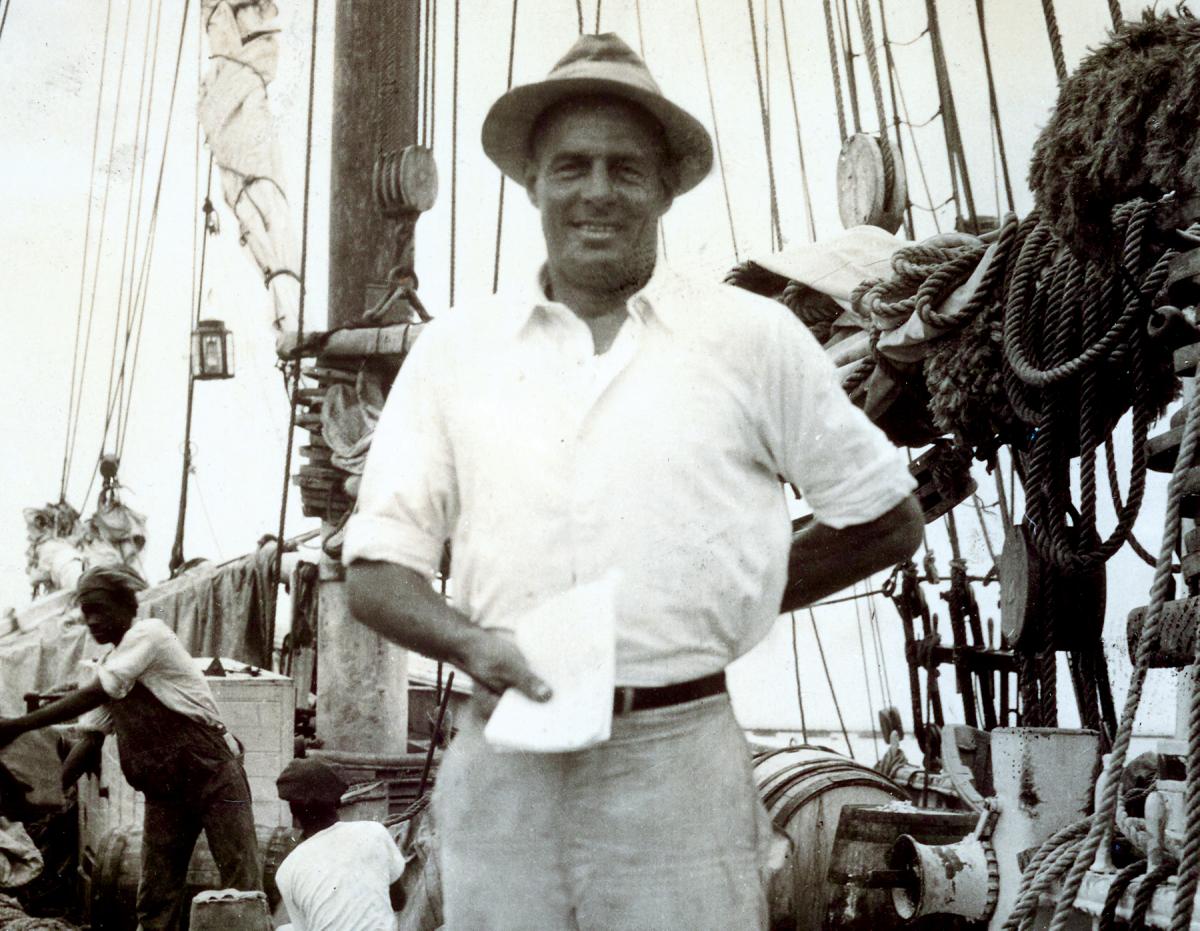

One of the first entrepreneurs to grasp the opportunity of this method was William “Bill” McCoy. Often credited with founding rum row, McCoy became one of the most well-known and hotly pursued rumrunners. He made his first trip with the Henry L. Marshall, a schooner refitted and reconfigured for smuggling. Instead of holding several tons of fish, she could haul 1,500 cases of alcohol. After refitting, he sailed her to Nassau, where he obtained a sham owner and reflagged her as British—a shrewd move, since U.S. vessels still were subject to U.S. law even when outside territorial waters.

After several profitable runs, McCoy bought a second schooner with a much larger cargo capacity. His new Aresthusa, reflagged as the Tomoka, could fit 5,000 cases in her holds. Although initially inclined to sell his first vessel, he decided to keep her to fill a charter to deliver a load of 1,500 cases to a rendezvous off Atlantic City in July 1921. He advanced his former first mate, Carl Anderson, to be her captain.

McCoy had every reason to believe the run on 1 August 1921 would go smoothly—after all, rumrunning was easy money and safe as long as a few basic rules were followed: Stay true to your contract, stay clear of the government’s notice, stay well offshore, and stay vigilant to avoid Coast Guard cutters. He left written instructions on board the schooner, which, among other things, directed the captain not to linger near territorial waters, but rather to keep 25 nautical miles offshore. This paper trail would prove to be McCoy’s undoing.

As expected, the Henry L. Marshall safely arrived off the New Jersey coast in late July. Captain Anderson, however, promptly began to break every one of McCoy’s rules. First, while the schooner was en route, the owner of the Henry L. Marshall’s cargo had received a better offer—$60 a case versus the $40 agreed on with the original buyer. He decided to break his contract and go with the new buyer. McCoy later believed this was the point at which the venture began to unravel. He was sure the disgruntled buyer tipped off the government as to the identity of his vessel and her cargo, the new rendezvous location, and the new buyer’s identity.

He may have been right. Articles advertising the Henry L. Marshall’s presence off Atlantic City, with a cargo of whiskey available for sale, began to appear in local papers on 27 July. Whether the source was the jilted buyer became a moot point when Captain Anderson gave an interview to a reporter who had come out on a boat to investigate the rumor. Not only did Anderson give details of his own modus operandi and the previous three trips, he also provided an excellent overview of maritime alcohol smuggling operations in general. The Henry L. Marshall now was most assuredly on the government’s radar.

In response, the Coast Guard cutter Seneca (CG-85) was dispatched from her homeport of New York City to investigate. The 204-foot, 1,250-ton cutter was a relic of the age of steam. Built for the Revenue Cutter Service in 1908, she had been intended for service towing or destroying the numerous wrecks off the Atlantic coast, and her 1,600-hp twin triple-expansion steam engines were designed for power, not speed. Flat out, she might hit 11 knots—slow, but still fast enough to overhaul the schooners and coastal freighters commonly employed to bring alcohol to rum row at this stage of the game.

The Seneca and her skipper, Commander Aaron L. Gamble, cruised off the New Jersey coast on the afternoon of 29 July. After scouting the area, the cutter anchored that night about three miles off Atlantic City. The next day, her crew ran drills and conducted training while keeping a sharp lookout for the suspected smuggler.

At precisely 1540 on 1 August, after two and a half days of uneventful loitering, Gamble ordered the Seneca’s anchor raised and directed her offshore at full speed on course ENE ½ E—about 079 degrees in modern compass terms. The cutter ploughed a straight furrow through a glass-smooth sea for 45 minutes, then abruptly changed course to the north for another 15 minutes before slowing to approach an anchored schooner. Most likely, Gamble had received a report of a sighting of a vessel fitting the Henry L. Marshall’s description.

As he slowed his cutter and launched a boat with a boarding team, Gamble recorded his position as five miles off Little Egg Inlet. While this was outside U.S. territorial waters and the schooner flew a British flag—which normally would have placed her beyond Coast Guard jurisdiction—the vessel had concealed her name and homeport with canvas covers. This gave Gamble justification to board and examine the schooner’s papers to establish her identity and nationality.

Once on board, Gamble’s boarding officer found no one in charge. Indeed, of the five persons on board only the supercargo—the person responsible to the owner for the management, buying, and selling of cargo—was sober enough to coherently answer inquiries. He reported that the master and mate had left in a boat for shore shortly before the Seneca had shown up. While he was unable to provide any ship’s papers or documentation, he was certain that the British flag and the vessel’s position meant that the Coast Guard had no authority to be on board. He was wrong.

The boarding team proceeded to remove the canvas covers, revealing the name Henry L. Marshall and a homeport of Nassau. The boarding officer also could see that “Nassau” had been painted over the word “Gloucester” on the vessel’s stern. This was the vessel they were looking for! The boarding party then found 1,250 cases of scotch whiskey in the vessel’s hold. Gamble decided that the lack of documentation of a legal transfer of flag to Great Britain gave him sufficient justification to bring in the Henry L. Marshall. At 1841, he took the schooner in tow and proceeded at half speed, around 4.6 knots, on a course to New York.

The vessel’s papers eventually were found, including two distinct sets of cargo clearance papers from West End, the Bahamas. One set cleared her with 1,500 cases of whiskey for Halifax, and the second declared her to be in ballast for Gloucester, Massachusetts. Given the 1,250 cases of scotch in the holds, it became clear that the “in ballast” paper was fraudulent and designed to allow the Henry L. Marshall to enter the United States after offloading her contraband. This haul was the Coast Guard’s first major alcohol seizure of Prohibition.

McCoy’s written instructions to the captain of the schooner also were found, clearly implicating the vessel in smuggling and suggesting the vessel’s reflagging was intended only to fraudulently remove her from U.S. jurisdiction. When pressed, several of the schooner’s crew quickly admitted the vessel’s smuggling activities not only on this trip, but on previous ventures as well. They provided additional incriminating details about McCoy as owner and the roles of the captain and mate.

In another break for the government, the boat carrying the master and mate had been seen entering Absecon Inlet, at the north end of Atlantic City, around the time of the Seneca’s boarding. In 1921, Coast Guard Station 123, Atlantic City, was sprawled astride Absecon Light, on the south bank of the inlet’s mouth. From this vantage point, Warrant Boatswain John M. Holdzkom, the station’s officer in charge, had noted the vessel passing his location. He was able to identify the local men running the boat as Harry Doughty, Daniel Conover, and Harry West; two others were on board.

This information enabled Prohibition enforcement agents to track down and arrest the Henry L. Marshall’s master, Carl Anderson, and mate, C. Thompson, in Atlantic City within three days. The agents also were able to identify Reuben Fertig, owner of a local saloon, as the intended customer—recovering several hundred cases of illicit whiskey from his establishment. Further warrants were obtained for John G. Crossland, the broker of the deal, and Bill McCoy as owner of the smuggling vessel. Crossland quickly was arrested, but McCoy would elude custody until Captain Gamble and the Seneca caught him following a dramatic chase and armed standoff with the Arethusa two years later.

Although McCoy’s lawyers and the government of Great Britain contested the seizure beyond the territorial sea, the United States asserted that an old maritime law, “An Act to Regulate the Collection of Duties on Imports and Tonnage” (March, 1799), gave Coast Guard officers authority to “go onboard ships or vessels . . . within four leagues of the coast” to examine manifests and cargoes to prevent smuggling. Both the U.S. Federal District Court and Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld this view, noting that Great Britain’s failure to protest when it was enacted and first enforced 122 years prior was tantamount to acceptance.

Over the next 11 months, the Customs Service and the Coast Guard together seized an additional ten foreign-flagged smugglers within U.S. waters. With its expanded jurisdiction, the Coast Guard alone bagged another eight beyond the territorial sea during the same period. While the Coast Guard would need another three years and a dramatic expansion in both personnel and cutters before it could effectively shut down rum row, the seizure of the Henry L. Marshall put rumrunners on notice that the area immediately off the U.S. coast was no longer a safe haven for smugglers.

Sources:

“An Act to Regulate the Collection of Duties on Imports and Tonnage, 5 Cong. Sess. III, Ch. 22” (March 1799), in The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America, vol. I, ed. Richard Peters (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 627.

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office 1922).

“Arrests Ordered in Seizure of Schooner,” New York Evening Post, 4 August 1921.

“Boatmen Arrested as Rum Carriers,” The New York Times, 10 August 1921.

“Florida Waters Said Infested with Craft,” The Athens [GA] Banner-Herald (24 July 1921.

Roy A. Haynes, prohibition commissioner, Prohibition Inside Out (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1923).

Logs of the USCGC Seneca, 27 July–2 August 1921, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

“Mystery of Booze Ship Solved, She’s the Marshall; Runs Booze Along Coast,” The Evening World (New York), 27 July 1921.

“Rum Ship Seized Under Act of 1799,” The New York Times, 14 August 1921.

“Schooner Used for Floating Bar off Atlantic City,” Tarrytown [NY] Daily News, 27 July 1921.

“Smugglers Wax Bold Off the Florida Coast,” The Daily Times-Enterprise (Thomasville, GA), 10 April 1922.

U.S. v. 1,250 Cases of Intoxicating Liquor, The Henry L. Marshall, 286 F, 260 (1922).

U.S. v. 1,250 Cases of Intoxicating Liquor, The Henry L. Marshall, Circuit Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, 19 June 1923, in “American Maritime Cases” vol. 1 (Baltimore: Niles and Knauth, 1923).

Frederick F. Van de Water, The Real McCoy (Mystic, CT: Flat Hammock Press, 2007).