Vice-Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson. Today, more than two centuries after his death, the name still evokes awe and respect among naval and military historians. Even though there have been dozens of contenders for the title, Nelson is still considered England’s greatest fighting admiral. How could this frail, one-armed, one-eyed man who was often ill and even seasick command great fleets in battle; outwit and defeat experienced French, Danish, and Spanish admirals; and earn the eternal respect of an entire nation? Nelson was a brilliant and innovative tactician, a popular leader who fought alongside his captains and sailors in some of the most legendary battles in history.

But in the summer of 1798, Horatio Nelson embarked on an impetuous sea chase that could have resulted in the loss of Great Britain’s most important colonial possession to the man who soon would change the course of history.

Destination: Egypt

The five-member French Revolutionary Directory impulsively declared war on Great Britain in February 1793. After conquering the Low Countries and securing a treaty with its old enemy Austria, France set its covetous eyes on the rest of Europe. Leading the campaign was the new commander-in-chief of the French Army, an aggressive 28-year-old Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte. His invasion and conquest of northern Italy in 1796 secured his status as a formidable and successful army commander.

For the Directory, the ultimate goal was the invasion of Britain. In February 1798, it sent Bonaparte to Dunkirk to determine what could be done. After examining the French fleet at Brest, the young general reported that any invasion of England would be “the boldest and most difficult task imaginable” so long as Britannia ruled the waves.

Bonaparte already was thinking ahead. He proposed, until the Channel fleet was fully prepared, that he should lead a fleet in the Mediterranean to seize Malta, invade Egypt, and threaten Britain’s most valuable colony, India. The capture of Egypt would close the shortest route to India and force England to take the long way around Africa to reach its rich colonial possessions in the Far East.

In March, the naval ports of Toulon and Genoa were a beehive of activity as the fleet was assembled, provisioned, and equipped. The invasion army consisted of 38,000 infantry, mounted cavalry, and artillery troops. It required 280 transports to carry the force to Egypt.

In command of the French fleet was the loyal and patriotic Vice Admiral François-Paul Brueys d’Aigalliers, who led from his splendid flagship l’Orient, a huge three-deck 124-gun behemoth. His naval force consisted of nine 74-gun ships-of-the-line, three more of 80 guns, and a squadron of frigates. Considering the size of the transport fleet, 55 French warships was a small escort force. Brueys requested additional warships from Brest, but the Directory refused on the grounds that the Brest fleet was diverting English attention from the Mediterranean.

Brueys was no coward, but neither was he a fool. While his ships-of-the-line were well armed, very few had experienced gunners. He was anxious to avoid battle with the well-trained Royal Navy. His voyage to Egypt was fraught with risk no matter what the arrogant young general asserted.

Brueys’ frigates would be herding 280 ships spread out over a 20-square-mile area. The Mediterranean Sea covered more than 950,000 square miles, but there were many narrow passages and choke points his vast fleet would have to transit on the way to Egypt.

Bonaparte had chosen l’Orient for his own command ship. Loaded with fine food and spirits for his comfort, the huge ship also carried more than 7 million francs in gold to finance the expedition.

Admiral Sir John Jervis commanded the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean fleet, with Gibraltar as his home base. Jervis had to expand his area of responsibility by watching the Spanish naval base at Cadiz, which was considered a threat to Britain’s last continental ally, defenseless Portugal. In the spring of 1798, Jervis received word from the Admiralty concerning an ominous naval buildup in the Mediterranean ports of Toulon and Genoa. He needed someone to command a squadron to approach Toulon and determine what the French were up to. He had just the man in mind.

Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson already was a hero in Great Britain, having been knighted and attaining flag rank after his audacious boarding and capture of two Spanish ships-of-the-line at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in February 1797. This cemented his growing reputation for boldness and innovative action. Already blind in one eye from a 1795 battle wound, Nelson commanded a disastrous July 1797 invasion of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands, in which more than 100 marines were killed and he lost his right arm when a musket ball shattered his elbow. But the injuries did not slow Nelson down; rather, they only added to his public notoriety.

Stormy Seas and AWOL Frigates

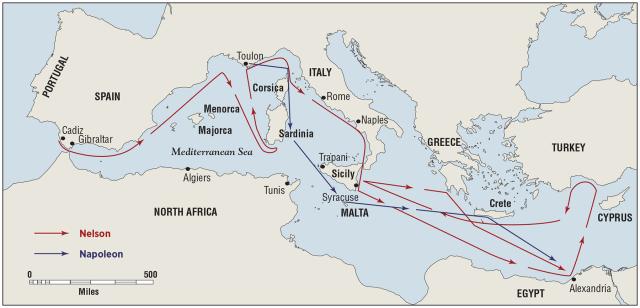

Nelson was on board the 74-gun HMS Vanguard as he joined Jervis in April 1798. The senior commander told him to take the Vanguard and two other 74s, the Orion and Alexander, plus three frigates into the Mediterranean. It was obvious a major amphibious operation was in the making. The destination could be any of half a dozen ports or islands of tactical or strategic importance, but Jervis and Nelson were certain Bonaparte’s goal was Egypt, from which he could seize Suez and threaten India. This would be a catastrophe for Great Britain.

On 8 May, the small squadron passed through the Pillars of Hercules and headed north. By 20 May, under cloudy but calm skies, Nelson was 70 miles south of Toulon. Suddenly, a savage gale tore out of the northwest and slammed into the ships. Fighting mountainous seas, the six vesselss were battered, but the Vanguard caught the worst of it. By the following afternoon, all three of her masts had gone over the side, leaving the flagship wallowing helplessly. Nelson signaled the Alexander to take the Vanguard in tow, but little progress was made. At last the ships-of-the-line managed to reach shelter off the coast of Sardinia. There the carpenters and crew set to work jury-rigging masts and spars.

But when the weather finally abated, Nelson was astounded to find his three frigates missing. The three frigate captains, having been separated from the ships-of-the-line in the storm, logically assumed Nelson would return to Gibraltar.

This was no small matter. While the bulk of the navy consisted of the 74-gun ships-of-the-line, the most essential ships were the smaller and more nimble frigates. Often carrying only 32 to 38 guns, they were never intended to fight in the line-of-battle. Instead, frigates were the eyes of the navy, scouting ahead of and around the fleet. They carried dispatches and often towed damaged and captured vessels.

Just when he needed them most, the frigates had left Nelson blind.

This played directly into Bonaparte’s hands. The French invasion fleet had sailed one day before the storm struck the British squadron. Bonaparte’s huge expeditionary fleet passed out of the Gulf of Genoa and headed south between Italy and Corsica.

Not only was Nelson blind, but he had to figure out where the French had gone.

Just then a brig, the Mutine, arrived and informed Nelson that Jervis was sending him ten more 74s and the 50-gun Leander. Nelson’s fleet would be “a match for any hostile fleet in the Mediterranean.” But Jervis, according to historian John Keegan in his book Intelligence in War, apparently was unaware Nelson was bereft of frigates and did not send any.

New orders from the Admiralty told Nelson “to proceed in quest of the armament [French warships] of the enemy at Toulon and Genoa. On falling in with said armament you are to use your utmost endeavors to take, sink, burn, or destroy it.” This would prove to be far more difficult than the Admiralty, Jervis, or Nelson could have imagined.

Pursuit Across the Med

On 7 June, 11 ships-of-the-line under Rear Admiral Thomas Troubridge hove into view. Three days later, the fleet set sail in pursuit of Napoleon Bonaparte. They took the most logical route, south along the Italian coast. Nelson learned that the French fleet had passed through the Strait of Messina in early June. But he had no information beyond that. In fact, Bonaparte already had struck his first objective.

The strategic island of Malta, located 70 miles southeast of Sicily, had been in the possession of the Knights Hospitaller, descendants of Crusaders, since 1530. On 9 June, the Maltese found their island ringed by a “forest of masts.” The French first tried guile to enter the port, but the Grand Master of the Knights refused. His tiny army of unmotivated mercenaries and knights had no chance against Bonaparte’s forces. The island surrendered on 12 June.

For the next week Bonaparte busied himself with organizing a government and setting up a secure line of trade with France. After provisioning the fleet, Bonaparte ordered Brueys to raise anchor and head east toward Crete.

The French fleet was still at Malta when Nelson reached Sicily. He was slowed by the need to inspect every major port along the way in search of the enemy. On 13 June he learned that the French had been seen off Sicily nine days earlier, headed east. Needing both information and frigates, Nelson put into Naples and requested three frigates. But the neutral Neapolitans refused, fearing French reprisals. It was at Naples that the British finally learned of the capture of Malta. But clearly the huge French fleet had not been assembled merely to take the tiny island.

To Nelson, this meant either Greece or, more likely, Egypt was the main target. He had few solid facts to work with, and even educated guesswork in such situations could lead to failure.

On the morning of 22 June, near the southern tip of Sicily, the fleet stopped a small brig whose master told Nelson that the French had left Malta six days earlier, on 16 June.

The audacious admiral’s eagerness led to his first real blunder. Early that same morning HMS Leander had spotted four ships on the eastern horizon and reported them to the Vanguard. But Nelson, certain the French had a six-day head start, ignored the sighting. The French had to be at least a hundred miles away, headed southeast to Egypt.

But Nelson’s information was wrong. Bonaparte’s fleet had left Malta on 18 June, only three days earlier. The four ships seen by the Leander that morning were in fact the trailing screen of Bonaparte’s fleet, only 30 miles away. They were within the Royal Navy’s grasp.

Keegan states that at this point Nelson, “uncharacteristically, consulted his captains as to what to do.” Nelson normally did not consult; he commanded. After hearing the opinions of four of his most experienced captains, he chose to head directly for Egypt, dismissing the evidence that the French actually were within reach. The fleet raised anchor and raced southeast

Hide-and-Seek at Sea

But Nelson was still blind. According to Laura Foreman and Ellen Blue Phillips in Napoleon’s Lost Fleet, “A fleet can never have enough frigates.” Nelson had none. In his writings, he lamented, “Were I to die at this moment, ‘want of frigates!’ would be stamped on my heart.”

With no other choice, Nelson spread out his 14 ships in a line as far as practicable. On a clear day, a masthead lookout, perched about 200 feet above the water, could see to the horizon about 12 miles away. His ships commanded a vista of 100 miles across and 24 miles in depth. Signals were sent by flag hoist, which could be discerned through a spyglass, but only on clear days. At night, lookouts had lanterns that could be seen from many miles’ distance. Signaling was accomplished by cannon fire and bells.

On the night of 22 June, with a dank fog shrouding the invasion fleet, Admiral Brueys stood on the quarterdeck of the huge l’Orient. Far away to the south, over the rush of water past the hull, the creak of rigging, and the flap of sails, he heard the distant muted booms of cannon fire. He was hearing Nelson’s ships signaling to one another as they pushed hard to catch the French. If just one of the nearly 300 transports showed a light, it could spell doom for Brueys’ magnificent fleet.

By the morning of 23 June, Nelson already was well past the French and leaving them in his wake. Sailing hard before a strong wind, he reached the Nile Delta city of Alexandria, Egypt, on 28 June. He reckoned that the French, limited to the speed of the slow transports, would have arrived in the ancient port at least a day before. All his ships were ready for action. But except for trading and merchant vessels, the huge port was empty. There was no sign of Bonaparte’s invasion fleet or warships.

Horatio Nelson was an excellent commander, a clever tactician, and a brave fighter. He was at his best in heated combat with the roar of battle around him. While he was rarely indecisive, he did sometimes question his own judgment. Such was the case on 28 June as he surveyed Alexandria. Where had he erred? Did Bonaparte have another destination in mind? Nelson endlessly paced the Vanguard’s quarterdeck. Yet he found no answer to the ultimate question: Where was the French fleet?

Inaction was not in Nelson’s character. The British ships raised anchor and headed east, then north along the Turkish coast, still searching for any sign of the French.

Again, Nelson’s impetuous nature had led him astray. General Bonaparte, resplendent in his gold-braided uniform, stood next to Admiral Brueys on board l’Orient as she entered Alexandria’s harbor. He had arrived at his destination without encountering any opposition.

Had Nelson lingered only 25 hours longer, he would have been waiting when Bonaparte arrived. Fate had dealt another winning hand to the French. Brueys had escaped annihilation by a single day. As events turned out, it was only a temporary reprieve. The invasion began and Bonaparte landed and drove his mighty army into Alexandria. The bulk of the French fleet, after leaving several frigates in Alexandria Harbor to protect the transports, anchored in a sheltered bay 12 miles farther northeast.

Found at Last—at Aboukir

Meanwhile, Nelson was fighting only with himself. As Captain Alexander Ball of HMS Alexander wrote, “His anxious and active mind would not permit him to rest for a moment in the same place.”

Finding the Levantine coast empty of French warships, Nelson turned west and skirted the southern coast of Crete. Then he compounded his error by heading back to Sicily. After beating against headwinds, his fleet anchored at Syracuse on 20 July. Nelson was now swimming in self-doubt. How could his fleet, spread out and alert, have sailed the length of the Mediterranean twice, a total of 1,800 miles, and failed to find the huge invasion fleet?

After poring over charts and again conferring with his captains, Nelson told them he was going to sail for Cyprus. The French had to be somewhere down there.

The British fleet left Syracuse on 25 July. On that very day, Napoleon’s army, having defeated the Egyptian Mamelukes at the Battle of the Pyramids, moved in to occupy Cairo. So far, Lady Luck had favored the French commander’s bold plan.

Then at last fate dealt Nelson a good hand. HMS Culloden, under Admiral Troubridge, had entered a port on the southern tip of Greece’s Peloponnesian coast and captured a French wine brig, which relayed shocking news: Napoleon had landed in Egypt a full month previously—only one day after Nelson had been there.

This news galvanized Nelson. He was vindicated in his insistence that Egypt had been Bonaparte’s goal all along. Nelson was not one to question his good fortune. He sent two ships, the Alexander and Swiftsure, to approach Alexandria and learn the disposition of the French fleet. They arrived on the morning of 1 August to find the French tricolor flag flying over the city and the harbor packed with hundreds of merchant ships and several frigates. But there was no sign of Brueys’ ships-of-the-line. Nelson then sent the Goliath and Zealous to search eastward to the only port that could support deep-hulled warships. And there they were, in Aboukir Bay.

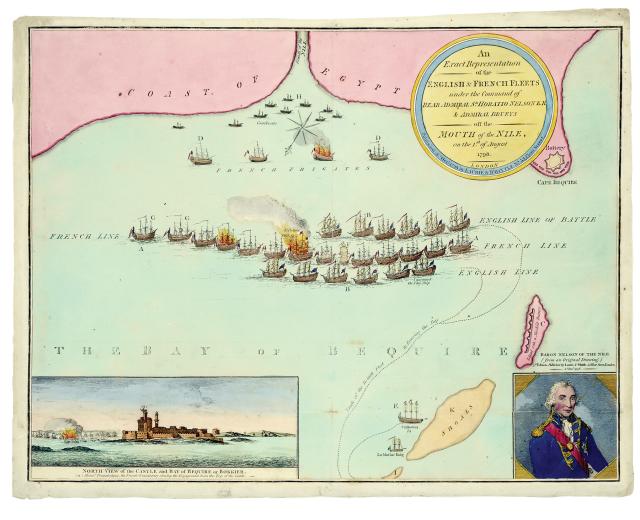

The British found 13 French ships-of-the-line and three frigates, with the magnificent l’Orient anchored in the center. The bay was semicircular, with the Rashid mouth of the Nile to the northeast and the fortified peninsula of Aboukir Point to the southwest. The 13 French 74s were riding at anchor with about 200 yards between ships. Brueys had anchored his ships only at the bow, leaving them to swing with the wind. As the leading British ship, the 74-gun Goliath, rounded the tip of Aboukir Island, Captain Thomas Foley, displaying the zeal and initiative of Nelson’s “Band of Brothers,” spotted the key flaw: Where there was room for a French 74 to swing, there was room for a British 74 to move in.

Passing the bow of the French 74-gun Guerrier, the Goliath turned sharply to port and slid into the landward side of the French line. At 1730 Foley unleashed a deadly broadside on the French warships. The Zealous, Theseus, Orion, and Audacious drove into the channel and began firing. Nelson raised his favorite signal: “Engage the enemy more closely.”

Crossfire Annihilation

Brueys, anticipating the British would attack from seaward, had ordered his gunners to load and ready the cannon on that side. The portside guns were not loaded or run out when the British ships came alongside. Even worse, the crews had piled stores and loose gear on the decks, making it virtually impossible to fight those guns. Every ship in the van of the French line was mauled by passing Royal Navy 74s. Each moved beyond the first ships and let go their sails and dropped anchor. While the first five British ships bombarded the port side of the French line, Nelson in the Vanguard led six more 74s into the attack from seaward. The French fleet was caught between two lines of British ships.

Nelson’s ships delivered a furious and concentrated close-range cannonade. The outnumbered French gunners were blown apart by British cannonballs as they desperately tried to load and fire their guns. This was the type of battle Nelson thrived on: to lay his ships directly alongside the enemy and batter them to flaming splinters.

As evening fell, the burning French ships cast a macabre orange glow over the bay. Flashes of gunfire strobed in thick clouds of powder smoke. Late in the evening the flagship l’Orient caught fire and burned out of control, prompting every ship in the vicinity to cut their cables and escape. The flames reached the powder magazines and the huge vessel exploded in a titanic detonation that crested in a fireball hundreds of feet high. Burning spars, guns, masts, planks, and bodies rained down on the battling ships. Admiral Brueys, the brave but reluctant fleet commander, never saw his ship’s death, having already perished when both his legs were shot off by a cannonball.

By the following morning Aboukir Bay was littered with floating wreckage and destroyed ships. Hundreds of dismembered and burned French bodies floated in the sea and washed ashore among the debris of their destroyed warships. The few remaining battered French ships fought valiantly all through 2 August, but the outcome was inevitable. Out of 16 French ships, only four frigates and one 74 escaped destruction or capture.

It was Nelson’s most stunning and complete victory. After the frustrating month-long chase around the Mediterranean he not only had found the French fleet, but had virtually annihilated it. Napoleon’s army was cut off from France. The Battle of the Nile was a disaster for the French general. Naturally, he blamed the dead Brueys.

A year later, Bonaparte abandoned his army, and leaving them to their fate, he escaped back to France, his dreams of conquering India in ashes. In the end, it was luck and daring that won the day for Nelson—but it had been very close to failure.

Roy Adkins, Nelson’s Trafalgar: The Battle That Changed the World (New York: Penguin, 2006).

Terry Coleman, The Nelson Touch: The Life and Legend of Horatio Nelson (New York: Oxford, 2004).

Laura Foreman and Ellen Blue Phillips, Napoleon’s Lost Fleet: Bonaparte, Nelson, and the Battle of the Nile (Silver Spring, MD: Discovery, 1999).

J. F. C. Fuller, A Military History of the Western World, Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo (Boston: Da Capo, 1987).

John Keegan, Intelligence in War: The Value—and Limitations—of What the Military Can Learn About the Enemy (New York: Vintage, 2004).