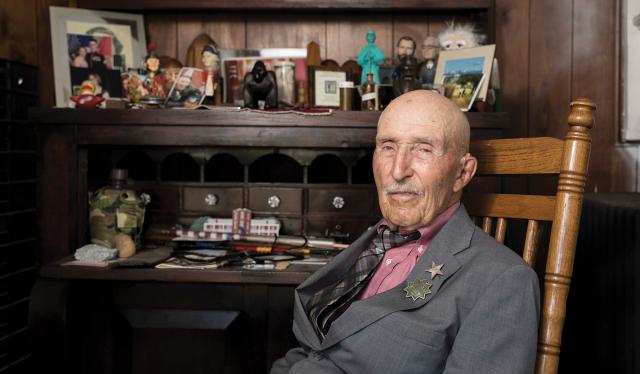

Remembering Ed Bearss (1923–2020)

Edwin Cole Bearss, longtime Chief Historian of the National Park Service and a giant in the field of historical preservation, died 15 September at the age of 97. He was a man of mythic proportions. He served his country with distinction as a Marine Raider in World War II. He fought, and was seriously wounded, in some of the most horrific campaigns in the Pacific. His wounds ended his combat career, but they never extinguished his love of the Marine Corps, nor did they end his service to his country.

With his encyclopedic memory and his celebrated battlefield tours, Ed was well known as a Civil War historian. Less well known are his contributions to naval history and maritime preservation. His involvement included the 1956 discovery of the well-preserved ironclad USS Cairo in the Yazoo River, where she had been sunk by a Confederate “torpedo” (mine). The subsequent raising of the Cairo in the 1960s ended with the salvage lift breaking the ship into large pieces, but that was not Ed’s fault, although he shouldered the burden that followed. Ed never gave up on the ironclad; the Cairo eventually was conserved and her pieces put back together to form a major exhibit of the ship, and the story of her crew, at Vicksburg National Military Park.

As Chief Historian of the National Park Service, Ed supported the first major study of America’s World War II vessels that were preserved afloat and ashore in various museums. That study saw many of those vessels designated as National Historic Landmarks by the Secretary of the Interior. Ed selected me, fresh out of graduate school, where I had gone with a yearlong leave of absence to get my master’s degree in maritime archaeology, to take the lead as project historian for the wreck of the USS Monitor.

“James,” he said in his call, “I hear you finished your degree,” and told me, albeit colorfully, to get myself to Washington for orders.

From there, we worked to create the nation’s first maritime preservation program, then called the National Maritime Initiative, now the NPS Maritime Heritage Program. With Ed’s backing, a national inventory of historic ships, lighthouses, and shipwrecks, as well as small craft, was completed. More than 140 historic ships were studied, and many were designated as National Historic Landmarks. Standards for preservation and restoration were completed. None of it would have happened without Ed and his guidance and support.

There were the occasional “covert missions” for the good of the cause that he also sent us out on: a trip to Britain to stir up support for U.S. involvement in the archaeology of the CSS Alabama. Trips to Capitol Hill to help Senator Howell Heflin write bills in support of U.S. involvement with both the Alabama, lying off Cherbourg, and the infamous 19th-century mutiny brig Somers, wrecked off Veracruz, Mexico. There was a secret mission to New Orleans to sort out some politics around Spain’s return of the Dedalo, the former USS Cabot (CVL-28).

Ed would end a conversation or a phone call with a simple, “Well, gotta go.” He’s gone now, but for all of us who knew and loved Ed, he’s never going to be forgotten. Semper Fi, Chief.

—James P. Delgado, archaeologist, author, and senior vice president, SEARCH Inc.

To read Naval History’s 2002 interview with Ed Bearrs, go to https://www.usni.org/naval-history/edwin-bearrss-interview.

Queen approves VC for World War II Hero

Queen Elizabeth II has approved the posthumous awarding of the Victoria Cross for Australia, the nation’s highest military honor, to Edward “Teddy” Sheean for his heroic actions in the Timor Sea in 1942. Australian Governor-General David Hurley (at lectern) and Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Michael Noonan made the announcement on 12 August. Sheean, an 18-year-old ordinary seaman from Tasmania, strapped himself to an antiaircraft gun and went down fighting, sacrificing his life to save 49 of his shipmates during the sinking of HMAS Armidale. Admiral Noonan remarked at the announcement that it was a “great day—for our navy, our nation, and a young Australian sailor who paid the highest price to save his shipmates from certain death.”

Much-Needed Repairs for the North Carolina

Since late summer, crews have been at work repairing the hull of the battleship North Carolina (BB-55) in Wilmington, North Carolina. The last major repair work was done in 1953, and the hull has critical structural issues that had to be addressed. The cofferdam around the ship was drained to prepare a dry work area, and crews have been cutting and replacing steel on the bow of the ship. Work on the steel is expected to continue through the fall. The contractor also will repaint the affected areas of the hull when finished. The battleship remains open to visitors for touring the main deck and above, and for watching some of the repair work firsthand. For more details, or to donate to the cause, visit www.battleshipnc.com/donate.

Centennial Expedition Honors Sunken Sub

It was a surreal moment on 1 September 2020 as three dive vessels made their way from the safety of their Cape May, New Jersey, harbor toward a blood-orange sun glistening in a sea of gold on the horizon of the open ocean. The beauty of the morning sky and calm seas made for a stunning cruise to the wreck site of the USS S-5 (SS-110).

The S-class submarine sank on 1 September 1920, but all hands survived, managing to escape the steel coffin and flag down a passing ship, and the loss of the sub thus was followed by a miraculously successful rescue.

On the surface, the 2020 trip was not much different from the thousands of trips made over dozens of years by this group of underwater explorers, the author included. But this trip was unlike any other previous one to the sunken submarine. The wreck divers were not just bringing hundreds of pounds of gear, steel tanks, closed-circuit rebreather technology, underwater camera rigs, diver propulsion vehicles, and the necessary lifesaving equipment wreck divers need at extreme depths.

This time, the divers also were bringing family members of one of S-5’s heroes, commanding officer Charlie Grisham, to the wreck site on the 100th anniversary of the submarine’s sinking.

After a topside ceremony in which 38 carnations (one for each survivor) were given to the sea in remembrance of the courage displayed in these same waters 100 years ago, the wreck divers traveled 27 fathoms to the remains of S-5.

For the divers, the descent to the sunken submarine was a descent into time. Hand over hand, they pulled themselves into history, 165 feet below the surface. Given the picturesque conditions topside and the gin-clear waters that cocoon the wreck, it was difficult to imagine the unrelenting horror 38 men faced for 37 hours.

A century beneath the waves has taken its toll on the submarine. The outer skin has rusted away, exposing the pressure hull. Open hatches beckon to the darkness inside. The conning tower still rises proudly. For the first time in 100 years, an American flag flew on S-5 when the divers attached the Stars and Stripes to the conning tower.

Returning to the surface, to 2020 from 1920, the divers were greeted by Grisham’s family members holding a unique piece of American history. They had brought along Grisham’s hat—the very one he wore while on board S-5.

—Erik A. Petkovic Sr.

For more on the story of S-5—the sinking, the rescue, and the shipwreck—visit https://www.usni.org/naval-history/wreck-of-the-S-5.