In 1897, William McKinley was inaugurated as 25th President of the United States. As an advocate of tariffs and protectionist policies, McKinley believed in supporting U.S. interests in Cuba and around the globe through diplomacy and tough negotiations. And yet, just over 12 months after his inauguration, McKinley would find himself leading the United States into war against a European power. Although America would enjoy total victory in 1898, this was despite the lack of naval preparation throughout the 1880s and 1890s. The near-immediate naval build-up in 1897 and early 1898 was due in large part to the bold actions of a capable Assistant Secretary of the Navy—Theodore Roosevelt.

The condition of the U.S. Navy in the post–Civil War era should serve as a cautionary tale for our present-day great-power competition. McKinley’s first 15 months in office highlight the need to be ready for war at all times and how easy it is to allow neglect of the fleet to create complete disorder. There are lessons to be learned from 1898 in the need for continuous maintenance in all areas of manning, training, and equipment, as well as realistic assumptions in planning and the need for bold action to accomplish both.

A Sad State of Affairs

“Ah! Capitaine, les vieux canons!” a French officer visiting a U.S. warship in the late 1880s exclaimed. He was genuinely nostalgic on see the antique weapons on board the vessel.1 That the administration of the U.S. Navy was in such disarray in the late 1880s was no secret. In the decades following the Civil War, a drawdown of the Army and the Navy, and a focus on domestic issues, had allowed the sea service to fall into shambles. What was surprising was the lack of attention on the status of the Navy even as naval issues were central to increasingly complex global politics.

In 1885, President Grover Cleveland’s first message to Congress included a scorching indictment of the Navy. “I deem it my duty especially to direct the attention of Congress to the report of the Secretary of the Navy, in which the humiliating weakness of the present organization of his Department is exhibited, and the startling abuses and waste of its present methods are exposed.”2 He goes on to hammer the Navy Department on training and readiness, wasteful spending, misdirected guidance, and the need for “all the talent and ingenuity” our country can afford.3 Throughout the 1880s, Italy, Spain, and Holland boasted a more powerful navy than the United States.4

The evidence of the need for a strong Navy, capable of power projection overseas, included aggressive competition for colonial possessions and an 1889 war scare between the United States and Germany over territorial claims in the Samoan Islands. Two years later, a mob attacked U.S. sailors on shore leave in Valparaiso, Chile, killing 2 and wounding 17 others. President Benjamin Harrison tried to take a hard line, but then backed off when he was informed that our Navy was actually weaker than Chile’s.5

These episodes compelled some politicians to call for more spending to quickly modernize the fleet, but additional funding was slow to materialize. As late as early 1897, the Navy still was woefully underfunded. While five battleships had been laid down, work was halted on three of them because the funds Congress had allocated for armor plate was too low.6

None of the pressing global issues drove Americans to demand a stronger navy. But most leaders in Washington were aware of the country’s relative weakness on the eve of war in April 1898.7 Without a doubt, the U.S. Navy was not ready for war.

Present-Day Parallels

Today, the Navy find itself in the difficult spot of trying to upgrade and implement new technology while also reconstituting a fleet that has been supporting demanding combatant commander requirements for years. While it does not suffer from severely outdated ships and equipment as it did in the 1880s, the Navy struggles with manning the fleet, training its people to maximum lethality, and carrying out planned maintenance. This is evidenced by retention and undermanning in multiple communities, the systemic training issues highlighted by the recent 7th Fleet incidents, F/A-18 readiness, and ship maintenance periods.

In addition, the American public more and more is disconnected from its military. Although supportive of men and women in uniform, the public is apathetic toward the operational needs of the military. Issues such as the constant delays in carrier maintenance or the severe gaps in fighter readiness do not register with the public or many of the politicians who represent them.

The lesson learned from nearly 20 years of neglect, from 1865 to 1885, is the need to forcefully message the vision, the need, and the lethal costs of waiting to prepare and fully invest in every part of the fleet. In 1880, the U.S. Navy was “good enough” for the expected but severely inadequate for the unexpected.

Strategic Visionaries

In early 1898, the Navy had large deficiencies in training, readiness, and capability. One thing the service was not lacking, however, was strategic thought. Although the United States and Spain had been at peace for more than 80 years, U.S. politicians and naval officers had contemplated war with Spain ever since that country’s 1868–78 Ten Years’ War against independence-minded Cuban rebels.

Affairs with Cuba dominated U.S. foreign policy throughout the late 19th century. Washington was determined to enforce the standards of the Monroe Doctrine. Continued instability, depression, extreme poverty, and violence threatened Spain’s ability to rule its Cuban colony in the face of the colonial ambitions of other powers. For the United States, the possibility of a different European power taking control of Cuba was unacceptable.

After the Cuban Revolution broke out in 1895, Americans began to align with the revolutionaries. Reports of Cuban civilians being put into concentration camps to separate them from revolutionaries and prevent them from providing aid to the rebellion became common; within two years, the concentration centers were being labeled death camps.8 As tensions continued to rise, the Naval War College was paying greater attention to the possibility of war with Spain. Naval strategists understood that a war with Spain would necessarily be a global conflict.

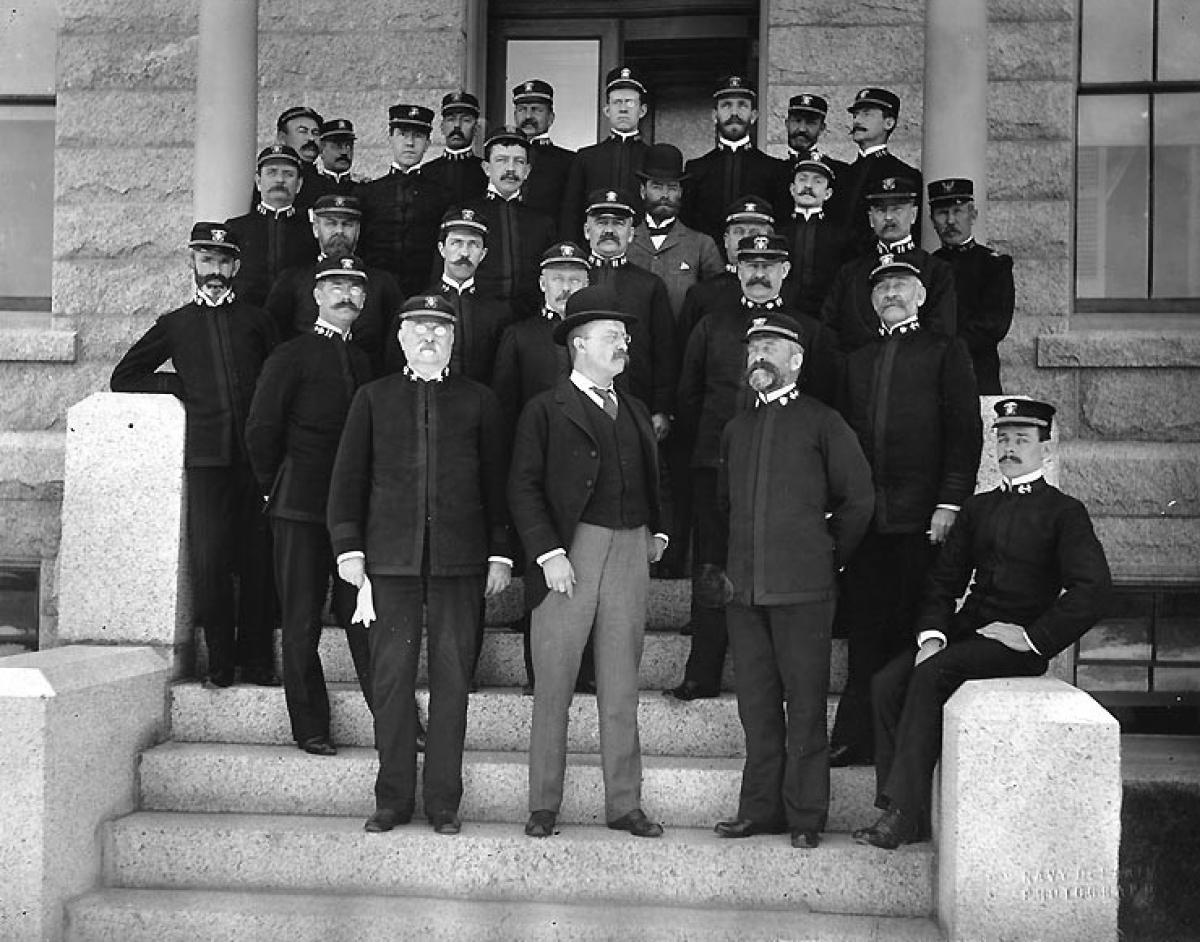

Over the course of his tenure at the Naval War College, Alfred Thayer Mahan saw to it that the institution not only gave officers advanced instruction in topics related to history and the technical side of naval warfare, but also ensured the “creation of the prime source of war plans for the government.”9 Theodore Roosevelt embraced this vision. In fact, only a few days after becoming Assistant Secretary of the Navy on 19 April 1897, Roosevelt ordered a review of two recent war plans and a new strategy “in light of recent developments in the Pacific and the Caribbean.”10

On 2 June, he delivered an address at the Naval War College in which he expressed his views on national preparedness, stating, “It has always been true, and in this age it is more than ever true, that it is too late to prepare for war when the time of peace has passed.”11 It was clear to Captain Caspar Goodrich, the college’s president, the new strategy should focus on war with Spain. “Special Confidence Problems” came down from Roosevelt for academic consideration.

The U.S. Navy’s new war plan, ready on 30 June, assumed a war with Spain for the liberation of Cuba. The plan included hostilities in the Caribbean, a blockade of Cuba, an invasion of the island, an attack on the Philippines and possibly even the Mediterranean shores of European countries.12 With the navy the United States currently had at its disposal, a tri-theater war likely would not have been possible. Military leaders were planning in a resource vacuum. In 1897, the U.S. Navy only had eight modern armorclads, including the battleship Oregon (BB-3), which was stationed on the West Coast. Comparatively, Spain had ten modern armored ships and outnumbered the U.S. Navy in every other class.13 Roosevelt recognized this and sprang into action to make the plan feasible.

Today, the United States has the world’s most powerful navy. While the reasons behind resource constraints may change over the decades, constraints will never go away. The lesson learned from the operational planning of the late 19th century is to consider actual resource availability in operational planning, whether our resource requirements for victory are feasible, and a plan to achieve those resource requirements.

Preparing for War

Roosevelt had been a supporter and consistent advocate for a bigger navy for more than ten years before he became Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Once in office, he became worried that there was “a foolish feeling growing that we now have enough of a navy.”14 He made it known that the United States’ future as a global power rested on the creation of a bigger and more capable Navy. When Roosevelt began his duties in the Navy Department, trouble with Spain was clearly on the horizon and the possibility of war dominated his thoughts. There were precious few ways for the Cuban situation to be resolved. Roosevelt was convinced that war was coming, and he knew the Navy would be the deciding factor between victory and defeat.

Roosevelt’s Naval War College address on 2 June 1897 was a call to arms. During the speech he demonstrated with examples that, upon a sudden attack, it would take six months for the United States to gain parity with any power. He also explained that there had never been a time to date when a war between two nations had lasted more than about two years, and the first 90 days normally prove decisive in a conflict.15

Roosevelt had all the technical details, he understood ships and armament, the importance of preparedness, and knew how strategically important it would be to seize the initiative in any attack on Cuba, along the Spanish coast, or in the Pacific.16 When Navy Secretary John D. Long left for a vacation two weeks later, Roosevelt went to work preparing the Navy for war.

In full, albeit temporary, control of the Navy Department, Roosevelt worked vigorously until he left to go to war himself in 1898. He signed orders to allow for general maneuvers by the North Atlantic Squadron, went aboard ships for gunnery practice, investigated the management of Navy yard facilities, pushed for the installation of rapid-fire weaponry throughout the fleet, wined and dined key senators and congressmen to secure funding and support, fired Navy Department personnel who did not meet minimum fitness report marks, directed the rewriting of war plans, inspected battleships off Sandy Hook, ordered munitions and armor, initiated a public relations campaign, set up boards to investigate ways of relieving chronic dry-dock shortages, and made regular trips to the White House, where he educated President McKinley in strategy.17 Additionally, Roosevelt ensured that “his man,” Commodore George Dewey, received command of the Asiatic Squadron.18

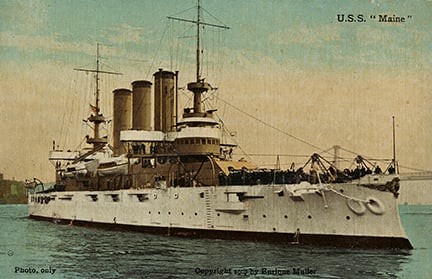

On 15 February 1898, an explosion split open the USS Maine (ACR-1) and more than 250 of her men went down with the ship in Havana Harbor.19 The Navy Department became an overnight sensation. Mail poured in, reporters were around every corner, and the mobilization of ships, yards, arsenals, and factories began. Shipyards went into overtime production. In addition to energizing shipbuilding at home, emergency preparations included movement of the fleets, ordering the Oregon to move from the Pacific to the Caribbean, and perhaps most importantly, searching the yards of Europe for additional ships that could be converted to use by the U.S. Navy.20

Arguably one of the most important orders given during this time was one from Roosevelt to Commodore Dewey on February 25, 1898. Roosevelt, seizing the opportunity while Acting Secretary, and sure that war was now inevitable, prepared for aggressive offensive operations in the Pacific: “Order the squadron except the Monocacy to Hong Kong. Keep full of coal. In the event of declaration of war [with] Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands. Keep Olympia until further orders.” Thus, Roosevelt set up the Battle of Manila and victory in the Philippines.

It is hard to imagine accomplishing as much change in the present-day U.S. Navy as Theodore Roosevelt achieved in 1897 and early 1898. There likely would be many more obstacles, including more levels of oversight, instant communications, and the 24-hour news cycle, just to name a few. Roosevelt’s willingness to shake up the accepted and standard way of doing business, his ability to identify problems and bold solutions, to find new pathways and shortcuts, led to U.S. success. He went to the limits of, and admittedly beyond, his authority, caring little for the risk to him professionally. His personal ambition to win the day far outweighed his personal ambition for his future. Where do we find such men?

The Ability to Course Correct

The “rebirth” of the U.S. Navy had begun around the time of Grover Cleveland’s first administration, in 1885–89. But the sea service truly was made ready for war thanks to the likes of Alfred Thayer Mahan and Theodore Roosevelt working from early 1897 to the outbreak of hostilities with Spain in 1898. The Navy had a champion, whether they were looking for one or not. One who had vision enough to anticipate the impending and intractable dispute with Spain.

Roosevelt knew that there “was no luxurious plentitude of time to prepare for trouble. It took years of hard labor to build one of the new armored ships, and a war could be fought and lost before even those already in the yards were finished.”21 He recognized the immediacy of a course correction to create a force ready for combat. The Navy has made great strides in technological research, production, and implementation, in tactics development, and in lethal programs of record. We must maintain the ability to course correct now in manning, training, and equipping for any possible contingency. We are certainly good enough today, but are we capable enough for tomorrow?

1. David Traxel, 1898: The Birth of the American Century (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998), 87.

2. George F. Parker, The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland (New York, NY: Cassell Publishing Company, 1970), 512.

3. Parker, Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland, 513.

4. George Dewey, Autobiography of George Dewey, Admiral of the Navy (New York: AMS Press, 1913, 1969), 154.

5. Traxel, Birth of the American Century, 88.

6. Traxel, 91.

7. Traxel, 124.

8. John L. Offner, An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain Over Cuba, 1895–1898 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 13.

9. Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York, NY: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1979), 597.

10. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 597.

11. Joseph Bucklin Bishop, Theodore Roosevelt and His Time (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1920), 77.

12. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 602.

13. Margaret Leech, In the Days of McKinley (New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1959), 168; and Naval Encyclopedia, 15 July 2017, https://www.naval-encyclopedia.com/the-war-of-1898. Accessed: 29 May 2019.

14. Bishop, Theodore Roosevelt and His Time, 82.

15. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 594.

16. Leech, In the Days of McKinley, 161.

17. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 600–11. Leech, 161.

18. Morris, 613–14.

19. Leech, In the Days of McKinley, 166.

20. Leech, 168–69.

21. Traxel, Birth of the American Century, 91.