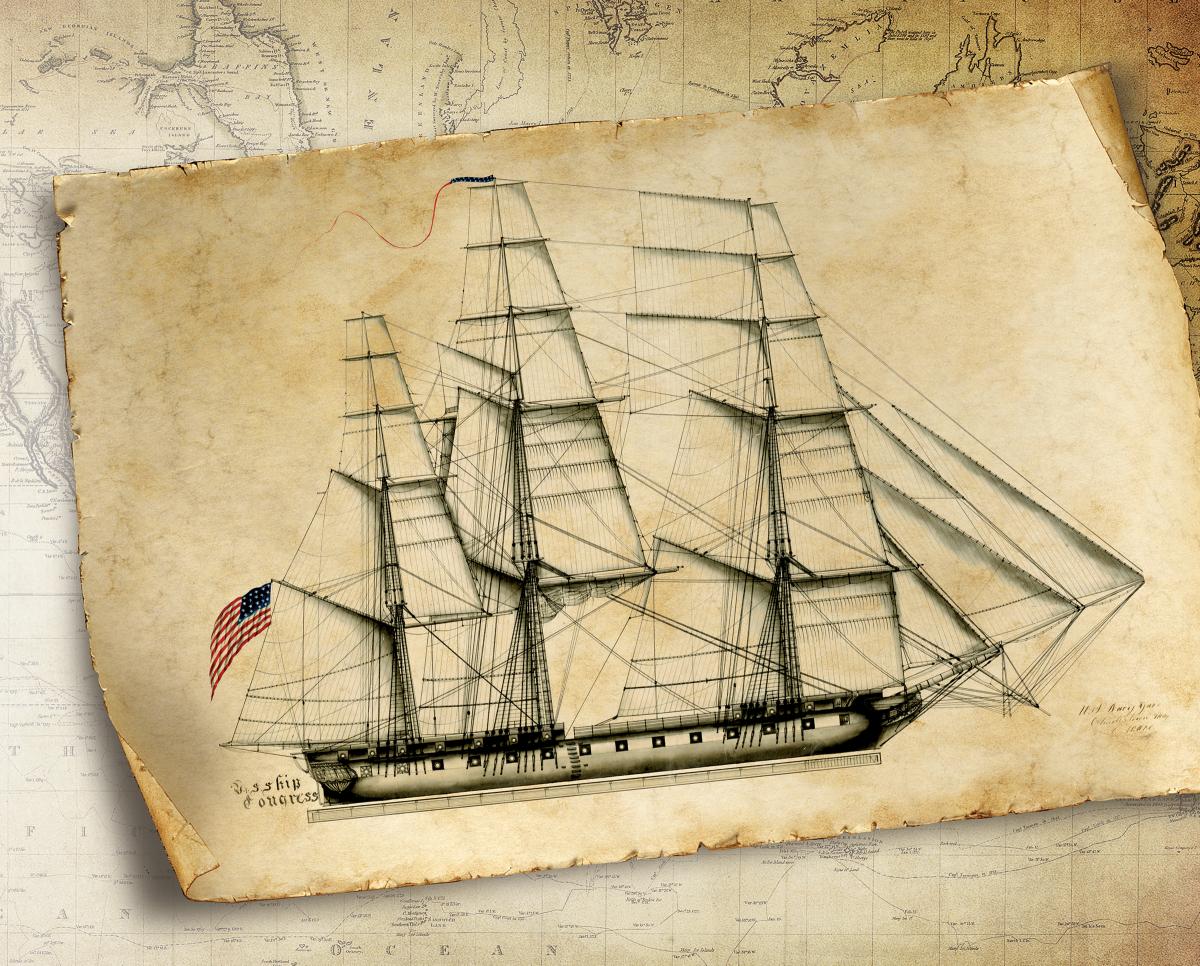

The skeleton of the 36-gun frigate Congress lay before John Hackett at his shipyard on the Piscataqua River in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in April 1796. He had laid the keel back in November 1795 and begun adding the rib-like frames every two inches along its length. Timbers for planking, diagonal riders, and knees rested in stacks for seasoning. Copper sheets for sheathing sat ready for bolting to the hull. There were stacks of coiled cables, masts, yards, and spars, and more arrived daily.1 Carpenters, joiners, blacksmiths, and other craftsmen worked in a flurry of activity to complete the warship.

The 57-year-old New Englander had run the Congress’ construction for the past two years. As a teenager, Hackett had fought in the French and Indian War. By the Revolution, he had established himself as a shipwright. He earned acclaim for building the Continental Navy frigates USS Alliance and Raleigh, as well as the 74-gun ship-of-the-line USS America. When Congress ordered the construction of the U.S. Navy’s first six frigates, Secretary of War Henry Knox requested Hackett specifically as one of the builders.2 Hackett and his men worked tirelessly to complete the Congress to defend U.S. commerce overseas and liberate U.S. merchants from Barbary corsairs.

Birth of a Navy

Across the Atlantic, on the North African coast, American sailors suffered slavery and imprisonment by Algerine corsairs. The Ottoman Empire claimed, but only loosely held control over, Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis. Along with independent Morocco, they made up the Barbary states. Although in decline for almost 200 years, Algiers was the most powerful among them. The city of Algiers sat high on a rocky hillside overlooking a harbor and had a population greater than 1790 New York, Philadelphia, and Boston combined. Despite most popular portrayals, the U.S.-Barbary conflict was not a modern democracy defending itself from medieval pirates. In fact, Algiers and the United States were quite similar. Both were slaveholding nations reliant on exporting grain and dominated by Europe’s naval and commercial powers. Barbary corsairs were more akin to privateers than pirates. They cruised under government command before European nations had even developed letters of marque.3

Algiers first targeted U.S. commerce in 1785. It seized two merchant ships and enslaved their crews. The score of American prisoners joined more than 3,000 Europeans held captive in Algiers.4 As was customary for the Barbary states, Algiers threatened more attacks unless it received an annual tribute and $59,000 to ransom both crews.5 The U.S. government under the Articles of Confederation took little action. Instead, it sold the last Continental Navy vessels in 1786. The new constitutional government did not start much better. The Senate did not agree on an appropriation for annual tribute to Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis until February 1792. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson appointed Continental Navy hero John Paul Jones as a commissioner to negotiate with Algiers on 1 June 1792.6 But Jones died five weeks later without reaching North Africa. His replacement, diplomat Thomas Barclay, died on 19 January 1793, also before entering Algiers.

The ruler of Algiers, Dey Hassan Bashaw, interpreted the eight years of delays as disrespect from the young nation. After establishing peace with Portugal in October 1793, he ordered his corsairs to prey on U.S. commerce in the Atlantic. An Algerine squadron of three xebecs—Mediterranean sailing ships used for trading—and a brig took four U.S. ships in a single day. By their cruise’s end, they had ten American ships and 105 additional prisoners.7 The news spurred the U.S. government into action. On 27 March 1794, Congress passed and President George Washington signed an act to provide a “Naval Armament.”8

The legislation called for building the original six frigates: the USS Constitution, United States, President, Constellation, Chesapeake, and Congress. Construction went smoothly for Hackett and the Congress for the next two years. But on 22 April 1796, Secretary of War James McHenry instructed Portsmouth Navy Agent Jacob Sheafe Jr. “to cause every operation to be immediately suspended.”9 American negotiators signed a Treaty of Peace and Amenity with Algiers on 5 September 1795.10 The Senate started debating the treaty on 15 February 1796 and ratified it on 6 March.11 To appease those wary of a standing military, the original Naval Armament Act ceased naval construction with the establishment of peace. On 15 March, however, President Washington urged Congress to continue construction on at least some of the warships. Congress agreed to continue with two of the 44-gun and one of the 36-gun frigates. Unfortunately for the Portsmouth builders, the Congress was not selected.

The Price of Peace

To secure the treaty, the United States agreed to a one-time payment of $600,000 (negotiated down from $2 million), $200,000 for releasing prisoners, and $21,000 in annual tribute. This was the largest single item in the 1796 U.S. budget.12

The war drums stopped beating in the United States, but the tenuous peace in North Africa started unravelling. David Humphreys, U.S. minister to Lisbon, warned Congress in April 1796 that the ruling faction’s control of Morocco, and peace with them, remained uncertain. Collapse of the Moroccan government threatened to imperil all U.S. commerce with Europe.13 In Algiers, the French consul openly campaigned against the United States with “all the mischief in his power.” He even armed a privateer that attacked a U.S. merchant ship.14 When Richard O’Brien, captain of the first U.S. ship taken by Algiers, went to London to withdraw funds to pay Dey Hassan Bashaw, he was denied. Between the millions still owed from Revolutionary War loans and now the sums owed to Algiers, the United States could not establish credit overseas.15

Joel Barlow, temporarily appointed U.S. agent to Algiers, arrived there in March 1796. He found the Dey irritated by the incessant delays in the diplomatic, and, more important, payment process. Hassan Bashaw was accustomed to dealing with European nations familiar with the generations-old practices of tribute and treaty payments. He reached his limit on 3 April and gave Barlow and another U.S. agent, Joseph Donaldson Jr., eight days to leave Algiers. Then, if no payment arrived within 30 days, he would consider the United States in violation of the treaty and send his corsairs after U.S. merchants.16

Under the advice of a broker in the Dey’s court, Barlow and Donaldson offered a 24-gun ship as a gift to the Dey’s daughter in exchange for an extension on the remittance. The Dey countered with a 36-gun ship for an additional three months. The Americans quickly agreed. Barlow explained to Humphreys, “We expect to incur blame, because it is impossible to give you a complete view of the circumstances, but we are perfectly confident of having acted right.”17

The Algerine fleet consisted of several tribute gifts, and Algiers annually received $24,000 from Holland, Denmark, Sweden, and Venice; $133,000 from France; $280,000 from Great Britain, and $3 to $5 million from Spain.18 Barlow explained:

Louis XIV said if there was no Algiers he would build one; as it would be the cheapest way of depriving the Italian States of their natural right of navigating their own seas . . . as long as the Powers of Europe will persist in this policy, whether we will or not, we must either be its victims or partake of its advantages.19

By “playing the game,” the United States stood to gain substantially. With peace established, shipping insurance rates would drop, revenues would increase, and the increased foreign trade would build much-needed credit in Europe.20

The Gift Frigate

The United States took great care in constructing the gift frigate. While the State Department interviewed former captives to discern the qualities the Dey would most appreciate, the War Department enlisted Josiah Fox, one of the designers of the first six frigates, to design the Algerine frigate. Secretary McHenry contracted one of the nation’s most renowned (and recently unemployed) shipwrights to lead construction—John Hackett. In July 1796, President Washington, disturbed over the lack of construction progress, wrote angrily to Secretary McHenry “to execute promptly & vigorously.”21 Building, however, was well under way. Washington realized his mistake and apologized to McHenry, but the exchange demonstrated the urgency of the frigate’s construction.22 The United States hoped for a higher standing with the Dey by providing a warship superior to those gifted by European states.

Meanwhile, plague ravaged Algiers. In the summer of 1796, 30 to 40 people died a day in the city of 60,000.23 With added urgency, Barlow continued to press for the American prisoners’ release when serendipity lent a hand. The Dey’s treasury ran low on specie, which gave the brokerages of Algiers greater influence. Barlow managed to convince one of the brokers to pay a portion of the U.S. debt in exchange for the funds he was arranging to come from Leghorn. With his coffer filled, the Dey released the Americans on 12 July, and Barlow had all those unaffected by the plague sailing for Boston by 13 July.24 For the original captives, their 11 years of imprisonment finally ended.

Disease also crippled the United States in the summer of 1796. While the yellow fever epidemic attacking Philadelphia stalled progress on the frigate United States, Hackett and his men remained relatively unaffected in Portsmouth. Other than delays in funds and materials, construction continued without incident. The husk of the aborted frigate Congress loomed over Hackett’s men as they worked on the Algerine frigate. After laying the keel and installing the frames, the assemblage of timbers began to resemble a ship.

The next spring, on 10 May 1797, the first of the original six frigates, the United States, finally launched in Philadelphia, but she grounded on the steep launchway. Not long after, on 29 June, the Algerine frigate launched. The frigate, named the Crescent by Secretary McHenry, had a 122-foot gundeck, 32-foot beam, 10-foot, 2-inch depth of hold, and displaced 600 tons. Hackett’s work neared completion as he installed the remaining masts and spars.

On 15 August, Fox reported Hackett’s contract complete. Timothy Newman, former Algerine captive and present captain of the Crescent, considered the frigate as “complete a piece of workmanship as he ever saw.”25 No contemporary illustrations of the frigate exist, but all accounts depict her with the qualities and craftsmanship expected from Fox and Hackett. The New Hampshire Gazette described the Crescent as “one of the finest specimens of elegant naval architecture which was ever borne on the Piscataqua’s waters.”26 A friend of Fox’s congratulated him, “You would be pleased I am sure to see the Frigate Crescent, riding at anchor the pride of our river and the boast of our seamen; indeed, she is a beautiful Ship & it is confidently asserted, the handsomest vessel, in the United States.”27

Although technically a frigate, the Crescent could not match the other U.S. warships under construction. Fox and Hackett did not take shortcuts on the frigate’s design or construction, but they made her as small as possible to still manage a 36-gun rating.28 The recently launched United States displaced almost 1,000 tons more than the Crescent and rated 44 guns, although she often carried 50 or more 24-pounders. The Crescent, once armed, carried 36 cannon: 24 9-pounders on the gun deck, 8 6-pounders on the quarterdeck, and 4 6-pounders on the forecastle.

It took several more months to acquire and store the cannon and payments still owed to the Dey. Finally, at 1000 on 18 January 1798, the Crescent sailed from Portsmouth for Algiers. On board the Crescent rode the new Consul General to Algiers, Richard O’Brien. The little frigate also carried almost 30,000 pounds of 9- and 6-pound shot; $100,000 worth of gunpowder, lead, timber, rope, and canvas; and four-and-a-half tons of silver dollars totaling $180,000 stored in 26 barrels.29

At full sail, the Crescent spread more than an acre of canvas.30 Foul weather tormented the gift frigate through the Atlantic passage, but, O’Brien explained, “the officers and crew made great exertions” to arrive safely at Gibraltar on 17 February 1798. The Crescent departed Gibraltar on 20 February and made Algiers on the 26th. The official delivery of the frigate occurred on 1 March, and the United States benefited immediately from the patched relationship. Three U.S. merchant ships were in Algiers’ harbor evading French and Spanish privateers when the Crescent arrived; now, they had the Dey’s protection.31 Hassan Bashaw already had helped U.S. diplomats negotiate treaties with Tripoli and Tunis—at substantially lower prices than he had demanded of the United States. When Tunis later refused the negotiated terms, Hassan Bashaw invaded the state to enforce them on behalf of the United States.32

Old Friends, New Enemies

As Captain Newman and the Crescent’s crew rode back to Boston on board the U.S. merchant vessel Sarah, a French privateer fired on them. The Sarah escaped, but other U.S. ships were not so lucky.33 The French Directory believed the Jay Treaty with Britain violated the 1778 Treaty of Alliance between the United States and France. After the United States refused to join France in its current war with Britain, France sent privateers to attack U.S. commerce. Three weeks after O’Brien delivered the Crescent, President John Adams revealed the events of the XYZ Affair, a U.S.-French diplomatic imbroglio, to Congress. In response, Congress established the Department of the Navy and nullified the 1778 Treaty of Alliance. On

16 July 1798, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert instructed Navy Agent Sheafe to “without delay take such measures as you shall judge best to compleat this vessel, with the greatest dispatch and the greatest Occonomy.”34 John Hackett was currently building the 24-gun subscription frigate Portsmouth, but he soon returned to complete work on the Congress.35

It took another year, but the Congress launched on

15 August 1799. On 9 January 1800, Captain James Sever took the frigate out to escort a convoy bound for the East Indies. Five days later, a strong gale completely dismasted the Congress. The frigate eventually limped into Hampton Roads for repairs on 24 February.36 The Congress would spend many long periods of her career laid up for repairs or in ordinary.37

Again to Algiers

The Napoleonic Wars consumed most of Europe’s attention in the beginning of the 19th century, which gave the Barbary corsairs considerable latitude. Great Britain even encouraged them against the Crown’s enemies. The little U.S. commerce not shut down by the British blockade in the War of 1812 suffered heavily from Barbary corsairs, especially Algiers. Within weeks of reestablishing peace with Great Britain, Congress declared a state of war with Algiers on 2 March 1815. By June 1815, Captain Charles Morris had the Congress sailing for North Africa in Commodore William Bainbridge’s squadron. It took 21 years, but the Congress finally sailed to war against the enemy that gave her life.

Bainbridge had his own score to settle with Algiers. In 1800, when commanding the frigate George Washington, he had been coerced to deliver tribute from Algiers to the Ottoman Sultan under an Algerine flag. When Bainbridge’s squadron arrived at Gibraltar, however, they discovered the other squadron under Commodore Stephen Decatur—Bainbridge’s subordinate—had already forced a new peace on Algiers under U.S. terms.38

Had the Congress reached Algiers in time, it would not have found her Portsmouth relative waiting. By 17 March 1800, O’Brien recognized signs of dry rot in the Crescent: “it is Very Visiable to me but I am in hopes. that this year she will be run on Shore. or taken by The Portugeese.”39 He explained earlier that “The Algerines are continually a building Gunboats but the[y] rot nearly as fast as they are built for want of care.”40 The Crescent must have suffered similar neglect. In 1805, Consul Tobias Lear reported the Crescent returned from a cruise with

the Captain Complaining that she was in such bad condition, and made so much water, that he could not keep the Sea. . . . The Dey would not suffer the Frigate to enter the Port but ordered her to keep out for the Cruize of 40. The Captain hesitating, was immediately dismissed and another put in his place, and the Frigate sent to Sea.41

By March 1806, the Crescent was unfit for service and broken up.42

The story of the Crescent should not be an embarrassment to the United States. The forgotten seventh frigate provides a better context for understanding the foundational years of the U.S. Navy and should be remembered

as an unfortunate but necessary step in the service’s development.

1. “Progress in Building Frigate at Portsmouth, N.H.,” in Dudley W. Knox, ed., Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers [hereinafter cited NDBP], 6 vols. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1939), 1:125.

2. Secretary of War to Henry Jackson, 2 July 1794, in NDBP, 1:76.

3. Gardner W. Allen, Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1905), 1–2; Hannah Farber, “Millions for Credit: Peace with Algiers and the Establishment of America’s Commercial Reputation Overseas, 1795–96,” Journal of the Early Republic 34, no. 2 (2014): 195–200, jstor.org/stable/24486687.

4. Richard O’Brien to the Congress of the United States, 28 April 1791, in NDBP, 1:28–30.

5. RADM Livingston Hunt, USN (Ret.), “Bainbridge Under the Turkish Flag,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 52, no. 6 (June 1926): 1,147–61, usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1926/june/bainbridge-under-turkish-flag.

6. Secretary of State to John Paul Jones, 1 July 1792, in NDBP, 1:36–41.

7. J. Fenimore Cooper, History of the Navy of the United States of America, 3 vols. in 1 (New York: G. P. Putnam & Co., 1853), 148.

8. “Act pertaining to the Navy,” 27 March 1794, in NDBP, 1:69–70.

9. Secretary of War to Jacob Sheafe, 22 April 1796, in NDBP, 1:151.

10. “Algiers—Treaty,” in NDBP, 1:107–16.

11. Frank Lambert, The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005), 82–84.

12. Lambert, The Barbary Wars, 81–82; Allen, Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs, 56.

13. David Humphreys to Secretary of State, 26 April 1796, in NDBP, 1:151–53.

14. Joel Barlow to U.S. Minister to Paris, France, 14 March 1797, in NDBP, 1:199–201.

15. Farber, “Millions for Credit,” 194.

16. Barlow and Joseph Donaldson Jr. to Humphreys, 3 April 1796, in NDBP, 1:143.

17. Barlow and Donaldson to Humphreys, 5 April 1796, in NDBP, 1:143–45.

18. Farber, “Millions for Credit,” 201.

19. Barlow to Secretary of State, 20 April 1796, in NDBP, 1:148–50.

20. Farber, “Millions for Credit.”

21. George Washington to Secretary of War, 13 July 1796, in NDBP, 1:165–66.

22. Washington to Secretary of War, 13 July 1796, in NDBP, 1:165–66; Washington to Secretary of War, 22 July 1796, in NDBP, 1:168.

23. “Passport Given by Joel Barlow, U.S. Agent, Algiers, to Ship Fortune,” 12 July 1796, in NDBP, 1:163.

24. Barlow to Secretary of State, 12 July 1796, in NDBP, 1:163–65.

25. Secretary of State to Barlow, 3 May 1797, in NDBP, 1:202–3.

26. Cooper, History of the Navy of the United States of America, 151

27. Edmund H. Quincy to Josiah Fox, 5 November 1797, in NDBP, 1:221–22.

28. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of the American Sailing Navy: The Ships and their Development (New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1949), 135.

29. “Ordnance and Military Stores for Algerine Frigate Crescent,” in NDBP, 1:218; Secretary of State to Timothy Newman, 23 December 1797, in NDBP, 1:230; Glenn Tucker, Dawn Like Thunder: The Barbary Wars and the Birth of the U.S. Navy (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1963), 102.

30. Fox to Secretary of the Treasury, 28 January 1797, in NDBP, 1:193.

31. Richard O’Brien to Humphreys, 1 March 1798, in NDBP, 1:239–40.

32. Humphreys to Secretary of State, 31 January 1797, in NDBP, 1:194.

33. Newman to Secretary of State, 7 June 1798, in NDBP, 1:251.

34. Secretary of the Navy to Jacob Sheafe, 16 July 1798, in Dudley W. Knox, ed., Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-War with France: Naval Operations from February 1797 to December 1801, 7 vols. [hereinafter cited NDQW], (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1935–38), 1:214.

35. Thomas F. Kehr, “Requiem for James Hackett,” Naval History 25, no. 6 (December 2011), usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2011/december/requiem-james-hackett.

36. Robert W. Neeser, “Historic Ships of the Navy, Congress,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 62, no. 3 (March 1936): 342–51, usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1936/march/historic-ships-navy-congress.

37. Chapelle, The History of the American Sailing Navy, 134–35.

38. Neeser, “Historic Ships of the Navy, Congress.”

39. O’Brien to Secretary of State, 17 March 1800, in NDBP, 1:351.

40. O’Brien to William Smith, 28 February 1799, in NDBP, 1:305–6.

41. Tobias Lear to John Rodgers, 25 December 1805, in NDBP, 6:326–27.

42. John Rodgers to Secretary of the Navy, 19 March 1806, in NDBP, 6:396–97.