Down in the engine room of an old four-stack Clemson-class destroyer that had seen better days, Chief Petty Officer William Bergstresser was less than halfway into the morning watch when a violent explosion shook the ship. The lights immediately went out, and in the darkness the chief made his way to a ladder that led topside, avoiding the loud hiss of steam emanating menacingly from the port side of the engine room.

When he emerged into the night air, he discovered “the whole forward part of the ship, including the bridge [was] completely demolished and carried away.” He soon learned that all the destroyer’s commissioned officers had been killed, leaving only Bergstresser and 43 of his shipmates, from an original crew of 159. Chief Petty Officer Bergstresser was no longer just in charge of the engine room—he was now in command of the Reuben James (DD-245), what was left of her.

As poignant as this account is, it is tragically typical when compared to the many stories of warship losses during World War II. But what makes this incident stand out is that the United States was not at war. It was Halloween night 1941, and the USS Reuben James (DD-245) had been operating in the North Atlantic, just off the coast of Iceland, as part of the so-called Neutrality Patrols that had commenced three days after the 1 September 1939 outbreak of war in Europe. From that time, the U.S. Navy had been working more and more closely with the British and Canadians as they struggled to keep the Atlantic sea lines of communication and supply open in a desperate attempt to prevent Britain from being starved by a German blockade conducted primarily by U-boats.

By the fall of 1941, several incidents involving the German submarines and U.S. destroyers had increased tensions and pushed both nations closer to war. In early September, the USS Greer (DD-145) and U-652 unsuccessfully attacked one another with depth charges and torpedoes, prompting President Franklin D. Roosevelt to declare, “From now on, if German or Italian vessels of war enter waters the protection of which is necessary for American defense, they do so at their own risk.” This “undeclaration of war” led to greater tensions and more questionably neutral activities, until the USS Kearny (DD-432) was torpedoed in the midst of a convoy and nearly sunk, suffering 11 dead—the first Navy KIAs in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Even the subsequent sinking of the Reuben James would not be enough to rouse the American people to seek revenge. But little more than a month later, U.S. isolationism would at last be erased by the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, causing the United States to declare war on Japan on 8 December 1941, with Germany and Italy declaring war on the United States three days later.

DDs and DEs

It soon became clear that the Allies’ key to winning the war would be to strike at the heart of Germany, and the best way for the Western Allies to do that was to use Britain as a staging area for a massive buildup made possible by the gigantic mobilization of U.S. industrial capacity. Producing the means to victory was one thing; getting that production across a submarine-infested ocean was quite another.

Destroyers (DDs) were there at the outset—firing the first U.S. shots and sustaining the first U.S. casualties of the war. And they would continue to be a key component of the convoy system, escorting virtually defenseless merchant ships across the Atlantic, using their sonar systems to detect U-boats and their weapons (depth charges and guns) to attack them.

But it was obvious that many more ships would be needed for the task, less expensive vessels that could be produced more quickly than destroyers. Shortly before the outbreak of the war, Britain had foreseen this need and begun building 208-foot Flower-class corvettes, more than 250 of which would serve as British and Canadian escorts for convoys.

“Destroyer escorts” (DEs) were the U.S. solution. Though about 50 percent larger than corvettes, DEs were smaller and slower than destroyers and had fewer guns and torpedo tubes. But they were roughly equal in antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capability, making them ideal for convoy duty. Seventeen different shipyards built more than 500 DEs of six different classes during the war.

The ‘Happy Time’

But as 1942 dawned, only 177 destroyers were in service in the entire U.S. Navy (83 of which were World War I vintage), augmented by only 17 Coast Guard cutters and a variety of small patrol craft. Eleven of the 92 U.S. destroyers in the Atlantic were sent to the Pacific theater, leaving only 81 as the U.S. contribution to Allied efforts to deal with the U-boat menace, which had been growing at a considerable rate.

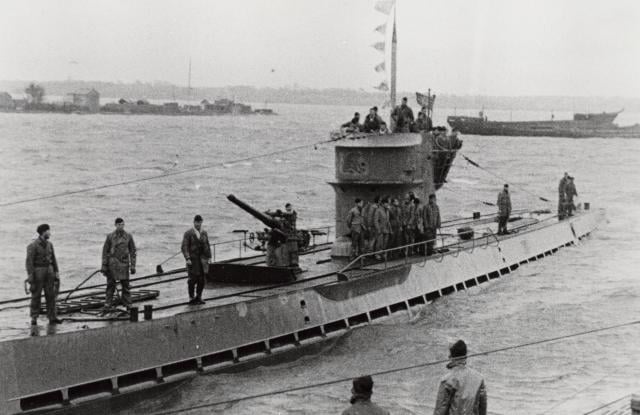

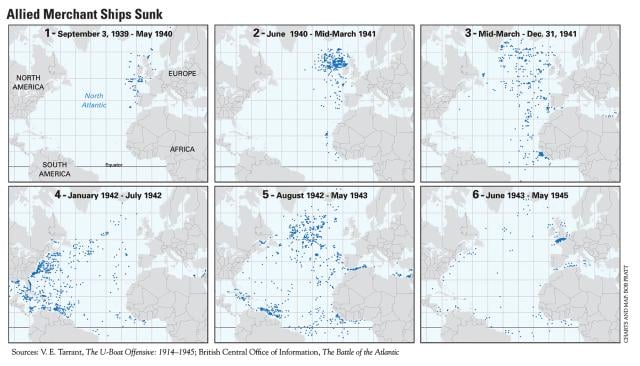

German Admiral Karl Dönitz lost no time sending an array of his U-boats to U.S. waters. Of his 64 submarines then in service (with 16 more coming off the ways each month), only 20 were the long-range Type IXs, capable of making the 3,000-mile trek to the East Coast and sustaining operations once there. But these proved enough for the Germans to commence Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat)—informally described by the Germans as the second of two “happy times” (the first occurring when the fall of France had brought U-boats closer to Allied shipping lanes).

Dönitz’s U-boats arrived off the Eastern Seaboard in early January and found a virtual turnpike of maritime traffic, with unescorted merchant ships flowing north and south along the American coast carrying oil from the refineries in the south, bauxite needed for the production of aluminum, and various other commodities vital to the coming war effort. Not only were these ships unescorted, they also were silhouetted against the bright lights of the East Coast, still burning brightly despite the recent declarations of war, making them easy targets for the newly arrived enemy subs.

U-123 drew first blood on 12 January, sinking the British freighter Cyclops off Cape Cod. Over the next seven days, a total of 13 more freighters were lost. And so it went. From January to August, Axis submarines sank more than 600 ships while losing only 22 U-boats. More Allied tonnage was lost during this period than had been lost in the previous two and a half years of the war.

Response

It was not until May 1942 that the Eastern Seaboard went dark, after commercial protests that dousing the lights would ruin the tourist season along the Atlantic beaches were overruled. “Bucket brigade” convoys also began to form. They would move in daylight for about 120 miles, anchor for the night, and then repeat the process the following day. With these measures, the “shooting gallery” was gradually shut down, so the Germans moved southward, where they enjoyed better hunting in the Gulf of Mexico for a time.

When defenses tightened there, too, Dönitz withdrew U-boats from U.S. waters and began a concentrated campaign in the North Atlantic that would last the winter of 1942–43 and prove to be a bloody one indeed. By then Dönitz had 382 boats, with more than a third at sea at any given time.

North Atlantic Allied convoys were now forming with regularity, and Dönitz focused on them in the region between Iceland and Greenland, particularly in the “air gap”—the area Allied aircraft could not reach from either side of the Atlantic. Forming “wolf packs” of submarines, the Germans set up patrol lines on both sides of the 300-mile-wide gap to intersect the convoys passing through. Unimpeded by enemy aircraft, the Germans were further aided by the reduction of convoy escorts, as a number were reassigned to Operation Torch, the November 1942 Allied invasion of North Africa.

A further drain on Allied naval resources occurred with the increased allocation of convoys to Russia. These additional convoys were deemed important, primarily as a symbolic commitment to the Soviets, whose participation in the war was essential. To make matters worse, German code changes temporarily set back Allied success in decrypting U-boat radio messages, and in March 1943, 82 Allied ships were sunk. Britain was suffering critical shortages, especially in fuel supplies. But in April, the losses fell off, with only 39 ships lost, while 15 U-boats were destroyed.

The Hunters Become the Hunted

Most historians agree that May 1943 marked the turning point in the long campaign. In that month—called “Black May” by the Germans—43 U-boats were lost, representing a full quarter of the operational boats of the Unterseebootwaffe. Dönitz called off operations in the North Atlantic, later acknowledging “we had lost the Battle of the Atlantic.”

There was no single reason for the change of fortune. Much has been made of the successful codebreaking at England’s Bletchley Park, but that is only part of story. One of the major factors was the increased production in U.S. shipyards, the key being the ability to produce more tonnage than was sunk. Also relevant was Roosevelt’s order to Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King to transfer from the Pacific 60 B-24 Liberators, whose long ranges decreased the air gap, increasing the U-boats’ vulnerability to air attack. Further additions in air assets came with the appearance of small but capable escort aircraft carriers (CVEs) that were being produced in growing numbers in U.S. shipyards. Their ability to enter the air gap along with the convoys significantly reduced the previous advantage enjoyed by the U-boats.

Technological improvements in radar, sonar, and high-frequency direction finding of radio transmissions (“huff-duff”), as well as new inventions such as the Leigh light (which aided maritime patrol aircraft in attacking surfaced U-boats while they were recharging their batteries at night), magnetic-detection equipment, antihoming torpedo devices, and hedgehogs (depth charges that were projected ahead of the attacker), also gave the Allies new advantages in the ongoing struggle.

‘A Helpless Fury and Dread’

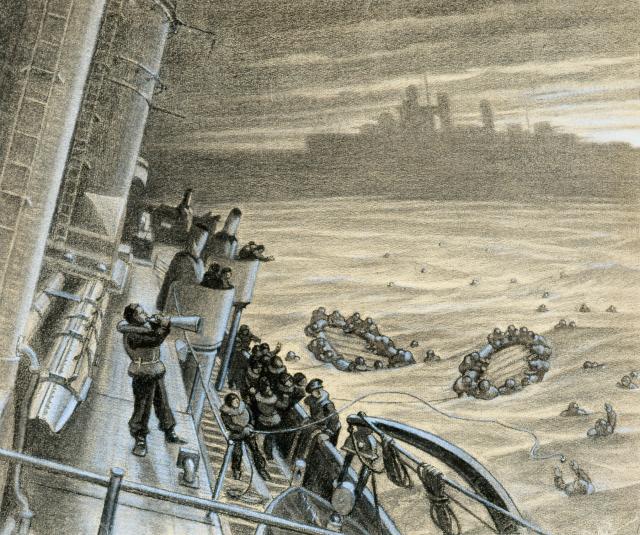

The single greatest contribution to the Allied victory was the implementation of the convoy system. By definition, a convoy consisted of two or more merchant ships under the escort of one or more warships, but typical transatlantic convoys during the war consisted of large numbers of ships—the largest composed of 166, with typical convoys consisting of 45 to 60 ships—steaming in 9 to 12 columns with 1,000 yards between columns and 600 yards between ships in the individual columns. Because of their extra vulnerability, tankers and ammunition ships were placed in the innermost columns, and the convoy commodore in charge would be in the lead ship in the center column.

Any given convoy was limited in speed to the slowest ship, so care was taken to build convoys around ships of similar speeds. Convoys were grouped according to the speeds of the merchants and were designated as fast, medium, and slow. Fast convoys typically ran at 13 knots and were used to transport troops, often 20,000 to 30,000 at a time. The medium (9–10 knots) and slow (4–7 knots) convoys generally carried only cargo.

Fast convoys usually zig zagged to complicate the U-boats’ targeting solutions, while slower and larger convoys usually steamed straight ahead because zig zagging further reduced speed and often caused confusion when used with a large number of ships. Individual ships sometimes used “evasive courses” (steering 20 to 40 degrees off base course) within the convoy if they were able. Larger convoys also increased the effectiveness of their escorts because the perimeter increased by only the square root of the total number of merchant ships.

Warships escorting the convoy, under an escort commander, would set up a screen about three to four miles from the convoy’s perimeter, ideally positioned so that their radar and visual ranges overlapped. If there were enough escorts available, a second group would precede the convoy at about five to nine miles distance, using radar and sonar to sweep ahead. For a successful depth-charge attack, escorts relied on a tight turning circle to enable them to quickly get their sterns over a detected target, and they used their superior speed to allow them to continue prosecuting an attack on a U-boat and then catch up to their advancing convoy.

In his monumental work, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Samuel Eliot Morison waxed poetic while describing convoys in his volume on the early years of the Battle of the Atlantic:

A convoy is a beautiful thing, whether seen from a ship or viewed from the sky. The inner core of stolid merchantmen in column is never equally spaced, for each ship has individuality. . . . Around the columns is thrown the screen like a loose jointed necklace, the beads plunging to port or starboard and then snapping back as though pulled by a mighty elastic under the sea; each destroyer nervous and questing, all eyes topside looking, ears below waterline listening, and radar antennae like cats’ whiskers feeling for the enemy. . . . On dark nights only a few shapes of ships a little darker than the black water can be discerned. . . . There is nothing beautiful, however, about a night attack on a convoy. . . . A successful attack is signaled by a flash and a great orange flare, followed by a muffled roar which tells that another ship has been hit. Guns crack at imaginary or too briefly glimpsed targets, star shell goes up, the rescue ship hurries to the scene of the sinking, and sailors in the other ships experience a helpless fury and dread.

Strategies and the End

It is important to note that, despite Dönitz’s concern about unsustainable U-boat losses, Allied strategy was not based on destroying submarines. It was based on the logistics of getting soldiers and supplies across the ocean to keep Britain in the war and enable a massive build-up of troops and war matériel there to make possible a cross-Channel invasion of “Festung Europa” to strike at the heart of Germany. Favoring Sun Tzu over Mahan, the Allies believed avoiding U-boats was preferable to destroying them. But German aggressiveness forced the many confrontations between submarines and convoy escorts.

For the Germans, the Battle of the Atlantic was a war of attrition that was doomed by U.S. ship production and the ability of escorts to exact a price that ultimately could not be paid.

In September 1943, U-boats resumed attacks in the North Atlantic, but after some initial success, they again experienced an unacceptable loss-to-kill ratio. After only four months, the submarines were withdrawn.

Despite making technological advances, the Germans simply could not keep up with their adversaries’ increasing power. Allied air attacks were growing more lethal, often sinking U-boats soon after they emerged from port to begin their patrols. The D-Day invasion of Europe led to the loss of U-boat bases in France, and as the Allies advanced into Germany, more than 200 U-boats were scuttled by the Germans to avoid capture.

Despite these many setbacks, U-boats continued to sortie and to attack, with crews often paying for their courageous audacity with their lives. The last attacks occurred just hours before the German surrender.

Sacrifices

The victors paid an extremely high price for their success, with 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships lost. But the losing side paid dearly as well. The total number of U-boats lost ranges from 648 to 760, depending on the method of counting (whether at sea or in port, geographic location, etc.), but most sources agree that more than 30,000 Unterseeboot sailors were killed in action. That represents three-quarters of all who went to sea in these denizens of the deep—the highest casualty rate of any service in modern history.

Despite many contributing factors to the outcome, in the final analysis the convoy system contributed most to the Allied victory in the Atlantic. The “happy times” when the Germans had the upper hand primarily occurred when the convoy system was not employed effectively and the deployment of wolf packs gave new hope. Convoys cost the Germans the initiative and ultimately the war.

Yet it was a dangerously close-run contest. Prime Minister Winston Churchill once ominously commented “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 2, Their Finest Hour (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1990).

Thomas J. Cutler, “What Were Their Names?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 138, no. 9 (September 2012): 92.

Marcus Faulker and Christopher M. Bell, eds., Decision in the Atlantic: The Allies and the Longest Campaign of the Second World War (Lexington, KY: Andarta Books, 2019).

Steven Howarth and Derek Law, The Battle of the Atlantic 1939–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994).

Terry Hughes and John Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic: The First Complete Account of the Origins and Outcome of the Longest and Most Crucial Campaign of World War II (New York: Dial Press, 1977).

Paul Kemp, Convoy Protection: The Defence of Seaborne Trade (London: Arms and Armour Press, 1993).

Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 1, The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939–May 1943 (New York: Little Brown, 1947).

Norman Polmar and Edward Whitman, Hunters and Killers, vol. 1, Anti-Submarine Warfare from 1776 to 1943 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015).

Norman Polmar and Edward Whitman, Hunters and Killers, vol. 2, Anti-Submarine Warfare from 1943 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016).

Timothy Runyan and Jan M. Copes, eds., To Die Gallantly: The Battle of the Atlantic (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994).

David Fairbank White, Bitter Ocean: The Battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1945 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).