The Greyhound—radio call sign for the fictional USS Keeling—in Tom Hanks’ new film of the same name is a Battle of the Atlantic convoy escort. But the real-life destroyer filmmakers used as her stand-in—the USS Kidd (DD-661)—earned eight battle stars in World War II’s Pacific theater.

The Kidd was laid down barely ten months after her namesake, Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, was killed on board his flagship, the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39), during the 7 December 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. The Fletcher-class destroyer was launched at the Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of Kearny, New Jersey, on 28 February 1943 and commissioned on 23 April.

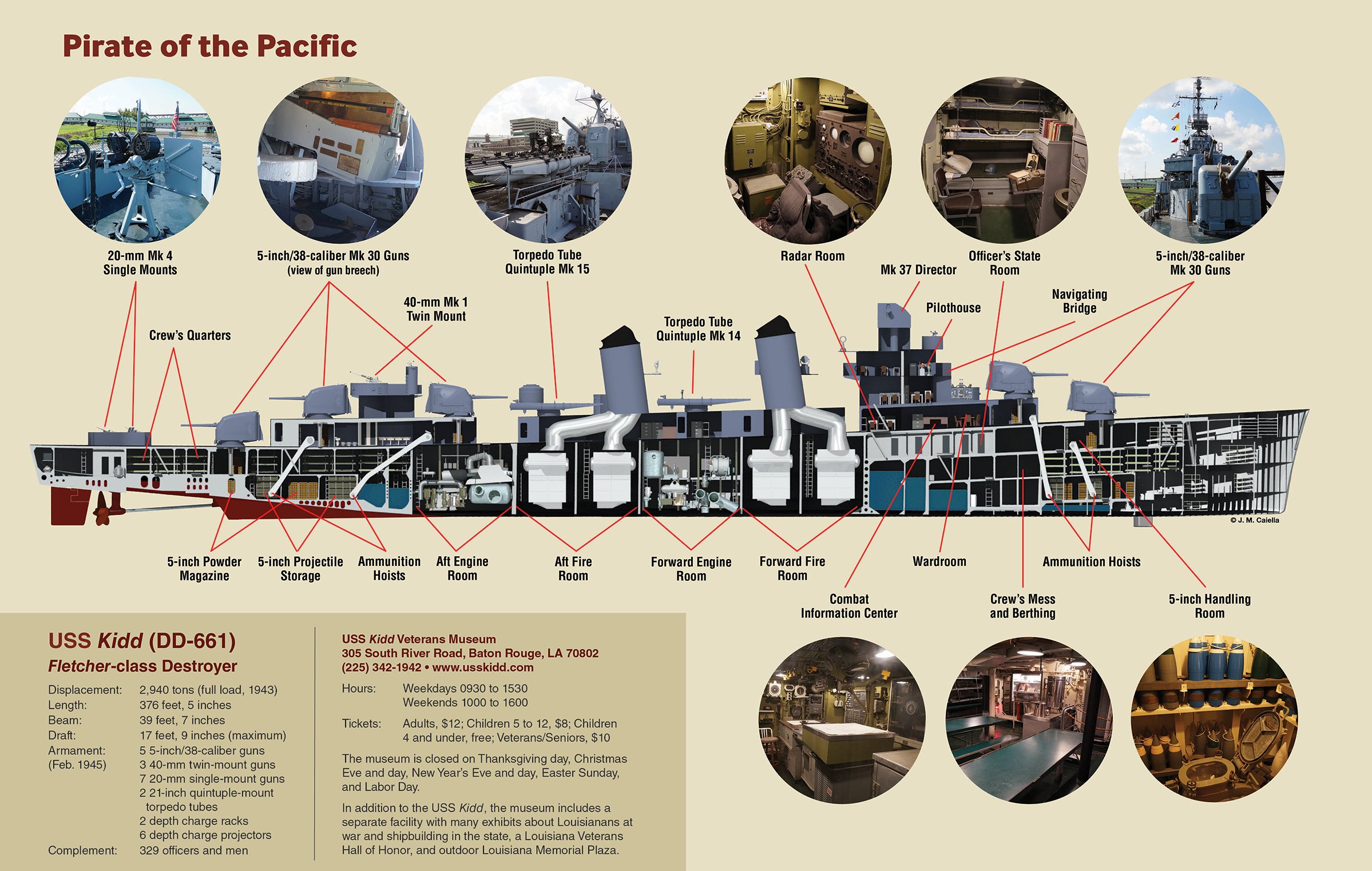

The crew adopted for the ship’s “mascot” the pirate William Kidd and paid a New York City artist $400 to adorn the No. 1 stack with a likeness of the seadog. The ship occasionally would fly the Jolly Roger, and her sailors later would call themselves the “Pirates of the Pacific.”

After a few months escorting task groups to, and covering the sea lines of communication out of, Argentia, Newfoundland, the Kidd got her first taste of fire—from a U.S. battlewagon. On 12 September, she was struck by two 5-inch star shells fired by the USS North Carolina (BB-55) during a simulated torpedo attack. There were no injuries, and the ship suffered only minor damage.

In early October, the Kidd and the rest of Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 96 were escorting carriers for attacks on Wake Island. Her combat diary noted that it “proved poor hunting, but it gave the ship a taste of rescue duty of which she was to see a lot more.”

Arriving back at Pearl Harbor on 11 October, she and the rest of DesDiv 96 departed ten days later to join Task Group 53.3 (on 5 November becoming Task Group 50.3) with the Essex (CV-9), Bunker Hill (CV-17), and Independence (CVL-22) to strike Rabaul. On 11 November, the group arrived at its launching position for the attack. Their planes conducted a strike that morning, but five minutes after aircraft began taking off for a second strike, a warning came of an impending Japanese aerial attack. About ten minutes later, at 1346, the Kidd was ordered to recover the crew of an Essex TBM Avenger that had crashed while taking off.

While the destroyer was maneuvering to rescue the aviators, 20 D3A Type 99 “Val” dive bombers bore in. At 1353, the Kidd stopped to pick up the Avenger crew, as the ship appeared to be under no immediate threat. However, between then and 1425, the Kidd maneuvered around the downed aviators “alternately engaging enemy aircraft, avoiding torpedoes, and conducting rescue operations.” Her action report cites eight aircraft as being “primarily Kidd targets,” and her commanding officer claimed three were definitely shot down by his ship, with another probable.

Later, during U.S. air attacks on Tarawa Atoll during the 19–23 November Gilbert Islands invasion, the Kidd’s radar provided the first warning of a large enemy force headed toward the fleet. She alerted other ships and began her battle with the enemy aircraft. “A Jap plane tried to crack into us but missed us and hit the drink. . . . At 5 o’clock 15 Jap bombers attack us,” 18-year-old Gunner’s Mate First Class Douglas L. Ridge wrote in his journal. The Kidd claimed two shot down.

The now-bloodied destroyer and her combat-seasoned crew returned to Hawaii for maintenance and rest. By mid-January 1944, she was in the midst of the Marshall Islands operation. She bombarded Roi and Kotje between 29 January and 8 February and from 20 March to 14 April was at Aitape and Hollandia. In June, she was off Saipan and in July and August off Guam.

After a brief refit at Pearl Harbor from the end of August through mid-September, the Kidd returned to battle: Eniwetok on 25 September, Manus on 3 October, and finally Leyte and the Battle of the Philippines from mid-October until early December. She then headed back to the states for a major overhaul and rest for her war-weary crew.

The overhaul lasted from 25 December through 10 February and included major enhancements to her antiaircraft batteries; notably, her forward 20-mm guns were replaced by heavier-hitting 40-mm guns, and she received an improved fire-control radar. She sailed from California on the 19th and joined Task Force 58 for the invasion of Okinawa.

By 16 March 1945, the Kidd and the other seven destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 48 were posted 30 miles in advance of the massive Okinawa task force. As radar picket ships, they were prime targets, and the ships suffered greatly. Nineteen picket destroyers were either sunk or so badly damaged by kamikaze attack that they were not repaired.

The Kidd screened battleships during their pre-invasion bombardments and, on 19 March, stood by the furiously burning Franklin (CV-13) through the first night of her valiant fight for survival. Through the rest of the month and early April she fought off suicide attackers, rescued downed aviators, and sank wayward mines, while continuing her early-warning picket duties.

On the afternoon of 11 April, DesDiv 96 was subjected to “numerous” attacks by Japanese aircraft. Thanks to the “excellent work” of combat air patrol (CAP) fighters and the division’s destroyers, the enemy scored only one hit—on the Kidd.

Shortly after 1345, the Black (DD-666) picked up an inbound raid on her radar, and just before 1400, one plane made for that ship, but the CAP fighters and the destroyer’s antiaircraft fire shot it down. Immediately thereafter, another made a suicide dive on the Bullard (DD-660), but it, too, was shot down, this time by the guns of the Bullard and Kidd. About ten minutes later, a lone plane dove out of the clouds toward the Kidd’s port bow and passed off the starboard bow, strafing the destroyer and being taken under fire by the bow 20-mm gun crews. Meanwhile, off the starboard quarter, two other aircraft appeared to be engaged in a dogfight. Most believed—and the action report states—that it was a ruse to make the Americans believe an enemy was being engaged by a friendly and thus not an immediate threat.

That changed when one peeled off in a diving turn to water level and headed at the Black, which was 1,500 yards off the Kidd’s starboard beam. At 1409, while under fire from the Black, it popped up over the ship and pushed back down to the wave tops, making for the Kidd. Because the plane was between both ships, neither could use their heaviest weapons against it. The Kidd’s 20-mm and 40-mm guns, while scoring hits, were not able to stop the plane, which smashed amidships at the main deck level just five feet above the waterline.

The plane blasted through the ship’s forward fire room, destroying the No. 1 boiler and steamlines in its path. A 500-pound delayed-action bomb it carried continued through the bulkhead and out of the ship, exploding just a few feet from the hull. The force of the blast destroyed the radar transmitter room, combat information center, and most of the decking and compartments on the port side up to the bridge deck and pilothouse.

Thirty-eight men died and 55 were wounded in the attack, but the Kidd maintained 22 knots throughout most of the subsequent combat. Smoke from her fire drew more enemy attention, but she and the Hale (DD-642) fought them off.

The Kidd had fought her last battle. After temporary repairs at Ulithi, she made for the West Coast and permanent repairs and late-war upgrades. The Kidd returned to Pearl Harbor in late August. But with the war over, she sailed to San Diego and was decommissioned on 10 December 1946.

The destroyer was recommissioned on 28 March 1951 and served two rotations in the Korean War, earning four more battle stars. She continued to serve in the western Pacific through 5 January 1960, when she was transferred to the East Coast. There, she was once again decommissioned, on 19 June 1964, and relegated to the backwaters of the Philadelphia Navy Yard mothball fleet. In 1982, she was transferred to the Louisiana Naval Memorial Commission at Baton Rouge, where she is the centerpiece of the USS Kidd Veterans Museum.