During the Civil War, the U.S. Coast Guard’s predecessor agency, the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, took an active part in the conflict. With cutters escorting convoys, enforcing blockades, serving as military command ships, participating in brown-water combat and shore bombardments, and providing security to their homeports, they were a vital maritime force in the conflict. But that was only after Southern cuttermen made the difficult decision to defend either the Union or their home states.

Choosing Sides

After the election of Abraham Lincoln as President, the nation began splitting apart. Loyalties were divided from the top down at the Treasury Department, the Revenue Cutter Service’s executive agency. Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb, a Georgia native, resigned in December 1860 to assist with the secessionist movement. Cobb helped establish the Confederacy and later served as a major general in the Confederate Army.

In 1860, the Revenue Cutter fleet was spread out, with cutters stationed in every major U.S. seaport. Like much of the nation, the sympathies of the cutter fleet’s personnel were divided between the North and South in the months leading up to the Civil War. Cuttermen, like their counterparts in the Navy and the Army, had to choose between serving the federal government and serving with their home states in the South. Before the start of the war, the Treasury Department lost two dozen experienced cutter officers and most of the cutters stationed in the South. For example, the captain of the Mobile-based cutter Lewis Cass turned over his vessel to Alabama state authorities, forcing most of his Union-leaning officers and crew to find their way back to the North.

Treasury Secretary John Dix tried to prevent turnover of federal revenue cutters to the Confederacy. Regarding the Southern-sympathizing captain of the New Orleans–based cutter Robert McClelland, Dix telegraphed the executive officer in January 1861, stating, “If any one attempts to haul down the American flag, shoot him on the spot.” Dix’s message became a famous slogan among Northerners, but many Southern cuttermen, including most men on board the Robert McClelland, chose to join the Confederacy.

Of all the Southern-based cutters, only the one based at Savannah, the William Dobbin, managed to escape to Northern waters. The rest were put to use as commerce raiders, blockade runners, and harbor defense vessels. For example, the cutter William Aiken was converted into the privateer Petrel and in July 1861 was destroyed by the USS St. Lawrence. In addition to the five cutters lost to the South, Union Navy officers destroyed a cutter at the Norfolk Navy Yard before she fell into Confederate hands. This effectively reduced the number of federal cutters from 24 to 18, with three stationed on the West Coast.

The Cutter Fleet Expands

The war necessitated a significant increase in the size of the Union Revenue Cutter fleet, not only to replace Southern cutters, but also to maintain traditional cutter missions under wartime pressure. Six cutters sailed from Great Lakes stations for East Coast bases, and nine former cutters serving in the U.S. Coast Survey were transferred back to the fleet for wartime duty. Cutters typically received the names of Treasury Secretaries and, ironically, the cutter named for Howell Cobb went ashore in a gale on 27 December 1861, en route from the Great Lakes to Boston, and was a total loss.

To meet additional needs, the service purchased several merchant steamers. With the increased need to interdict wartime smuggling, supply guard ships to Northern ports, and enforce the Union blockade, the service built an additional six steam cutters that joined the fleet in 1864.

Deep-Water Operations

During the Civil War, revenue cutters were called on to perform a multimission combat role. Under the command of Captain John Faunce, the cutter Harriet Lane sailed from New York to Charleston to escort relief ships destined for besieged Fort Sumter. On the morning of 13 April 1861, during the Confederate bombardment of the fort, the Harriet Lane spotted an unidentified steamer approaching the harbor and showing no colors. Exercising her right to stop an unidentified ship, the Harriet Lane fired a shot across the ship’s bow. In short order, the Nashville identified herself as a U.S. vessel by hoisting the Stars and Stripes. For this action, the Harriet Lane is credited with firing the first naval shot of the Civil War.

During the conflict, cutters also were called on to support Union Army and Navy operations by bombarding enemy positions ashore. After attempting to relieve Fort Sumter, the Harriet Lane received orders for escort duty, blockade operations, and fire support in eastern Virginia and coastal North Carolina. As part of the James River Flotilla, the revenue cutter gunboat Naugatuck not only exchanged fire with the ironclad CSS Virginia, but also shelled Confederate batteries at Sewell’s Point, Yorktown, and Drewry’s Bluff on the James River.

Because of their accommodations and shallow draft capabilities, various cutters became command vessels for other military branches. The Harriet Lane was transferred to the Navy after the Hatteras expedition and served as command vessel for Commander David D. Porter’s flotilla of mortar schooners that sailed with Admiral David Farragut’s expedition to capture New Orleans. In May 1862, President Lincoln, War Secretary Edwin Stanton, and Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase boarded the cutter Miami and cruised from Washington, D.C., down the Potomac River to Fort Monroe. The Miami became Lincoln’s presidential command ship, from which he ordered a 9 May reconnaissance of the shore near Norfolk. The next day, the Miami covered the landing of 6,000 Union troops, who occupied Norfolk after a hasty evacuation by Confederate forces. The cutter Nemaha also served as command vessel. She hosted Major General John Foster, commander of the Army’s Department of the South, in his historic meeting with Major General William Tecumseh Sherman. This December 1864 encounter marked the end of Sherman’s “March to the Sea.”

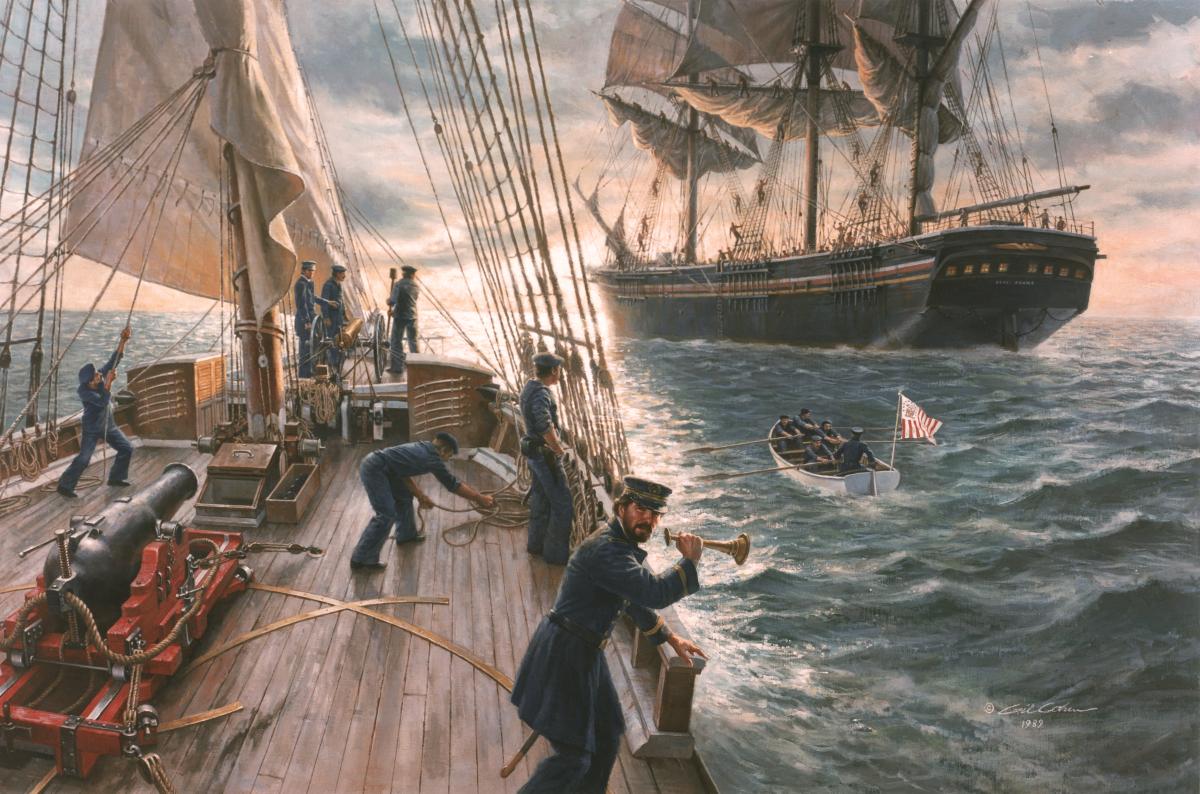

The cutters received further tasking during the war, including escorting convoys and enforcing the Union blockade of the Southern coast. In July 1861, the cutter Morris sailed from Boston in search of the Confederate privateer Jefferson Davis as she cruised the North Atlantic. During the blockade, the cutter Cuyahoga seized the merchant vessel Pride of the Sea, while other cutters also seized illegal vessels.

Inland and Costal Operations

In addition to deep-water operations in support of the blockade, revenue cutters performed invaluable services in the estuaries and inland waterways along the coasts. These operations primarily took place from the Chesapeake Bay south to Florida. The Navy commended the Agassiz for “the gallant part taken by that vessel” in defense of Fort Anderson, on North Carolina’s Neuse River. The Henrietta helped capture the Confederate stronghold at Fernandina, Florida; the Reliance engaged guerrilla fighters along the shores of the Chesapeake; and the Nemaha engaged Confederate batteries and supported Union troop movements on the Georgia Coast.

As an armed maritime police force, the revenue cutters also were called on to provide security for their homeports. As the Union occupied parts of the Gulf and the southeastern coasts, revenue cutters took up stations at ports such as New Orleans to fulfill their traditional missions. At major Union ports, cutters enforced federal laws on all vessel traffic. At the larger ports, cutters might board as many as 20 vessels per day. For example, the Baltimore–based Hope boarded outbound steamers on a daily basis and frequently found hidden war matériel destined for the Confederacy.

Cutters regularly seized vessels caught smuggling, breaking laws, or running the blockade. For example, the cutter Henrietta seized the schooner Adelso for attempting to run the blockade, and the Hercules seized the schooner Ann Hamilton in a similar case. The cutter Tiger served as a guardship for Washington, D.C., and was stationed at the Washington Navy Yard ahead of a feared attack by Confederate forces in June 1863.

Cuttermen boarded merchant vessels, searched for illegal cargoes, enforced federal laws, and protected commerce from enemy cruisers. The dangers of this duty were demonstrated by the cutter Caleb Cushing. In June 1863, she was captured by a boarding party from the Confederate raider Archer and set on fire off Portland, Maine. The cutter was destroyed; however, no lives were lost in the action and the Confederate raiders all were captured. Revenue cutters maintained privateer patrols off the coast of Maine for the rest of the war.

Maritime interdiction required a force experienced in boarding foreign and domestic vessels. Cutter crews did so for a variety of reasons. These included checking papers and vessel safety and stemming the flow of illegal cargoes, such as slaves or war matériel. In addition, cutters boarded ships destined for U.S. ports to check for illegal immigrants or overcrowded vessels. In July 1861, a boarding party from the cutter Morris came aboard the merchant ship Benjamin Adams, carrying 650 Scottish and Irish immigrants. Cutters occasionally intervened in mutinies, such as the one put down by the Shubrick in 1862 on board the ship Vitula, taking off 19 crewmen in irons to the San Francisco jail. And, on 21 April 1865, revenue cutters in the Chesapeake Bay were ordered to search for the assassins of President Lincoln in all outbound vessels.

As a tradition of the sea, revenue cutters had provided humanitarian assistance to those in distress since the service’s founding in 1790. This practice became such a regular duty that Congress formalized it in 1837. The cutter fleet continued its rescue mission during the war, aiding an average of 115 vessels in distress each year between 1861 and 1865.

Cutters on the Cutting Edge

The Civil War served as a catalyst for change within the ranks of the cutter crews and provided a foothold for minority service opportunities. While African Americans tended to hold lower status and service positions on board the cutters—such as cooks, stewards, and seamen—they fought side-by-side with white shipmates during combat. And wartime needs increased their numbers to as much as 10 percent of the cutter crews. These greater numbers served as a de facto integration in small cutters and increased African American participation to a level unheard of before the war.

Similar to the Navy, the Revenue Cutter Service’s fleet greatly expanded during the war and changed from sailing ships to primarily steam-powered vessels. In 1865, the fleet included 35 ships stationed in ports throughout the Great Lakes and along the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf Coast and two cutters in the Pacific. In that year, two-thirds of the cutters were powered by steam, compared to the 1861 wartime low of 18 cutters, only one of which had steam power.

Nowhere was the service’s technological transition more apparent than in the revenue gunboat Naugatuck. The ship featured twin screws for power and maneuverability and rubber-sealed ballast tanks with high-speed water pumps for partial hull submergence and low-profile protection. She also boasted an under-deck muzzle-loading system, so the gun crew could remain below decks during combat. During the war, the Naugatuck served in the James River Flotilla and as a guard ship in New York Harbor.

The Civil War cemented the role of the Revenue Cutter Service in its traditional missions of port and coastal security, maritime interdiction, and search-and-rescue operations. In addition, cutter combat operations reinforced the service’s reputation as a useful branch of the U.S. military. The Revenue Cutter Service had proven its worth.