They should have been in Hawaii.

Instead, the crew of PN-9 No. 1 was bobbing around the middle of the Pacific—thirsty, starving, and sunburned—and staring at a frenzy of sharks trailing their flying boat. Commander John Rodgers, Naval Aviator No. 2, took the predators’ presence in stride. He and his crew already had run out of gas, run out of food, survived an emergency sea landing, and been lost by the U.S. Navy. Sharks hardly made things much worse.

Days earlier, on 31 August 1925, Rodgers and his crew had embarked on the first overseas flight to Hawaii, beginning an anticipated nonstop, 28-hour voyage over 2,400 miles of open ocean. Tens of thousands of people had gathered around San Francisco Bay to witness the takeoff of PN-9 No. 1 and its sister flying boat, PN-9 No. 3, each loaded with more than a thousand gallons of gasoline. The flying boats were so saddled with fuel that PN-9 No. 1 failed to achieve liftoff during its first run across the bay. Not until its second try, when loose fuel cans and all the crew save the pilot had been shifted aft, did it take to the air. Cowds watched as the two large flying boats flew slowly past Alcatraz Island and through the (yet to be bridged) Golden Gate. Then the aircraft were off across the vast Pacific.

The Navy had crossed an ocean by air before, but in hopscotch fashion. In 1919, Lieutenant Commander Albert Read and a crew of five piloted an NC-4 floatplane across the Atlantic in 19 days. Departing from New York City on 8 May, the NC-4 made stops for refueling or repair in Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and the Azores before reaching Lisbon, Portugal. This accomplishment was eclipsed just weeks later, however, when British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown made a nonstop flight over the Atlantic between Newfoundland and Ireland, safely crash-landing their Vickers Vimy biplane into an Irish bog. Then, in 1924, two U.S. Army planes fitted with pontoons completed a round-the-world trip, taking half a year to travel about 27,000 miles across 21 countries.

All these flights were incredible accomplishments yet lacked the panache ultimately displayed by civilian Charles Lindbergh. On 20 May 1927, the young American airmail pilot began his historic, solo, nonstop flight from New York to Paris in the single-engine monoplane Spirit of St. Louis, arriving in France the next day after flying for more than 33 hours. But two years before this epic, world-changing flight, the Navy nearly preempted Lindbergh’s accomplishment by sending its flying boats in the reverse direction over a different ocean—west across the Pacific to Hawaii.

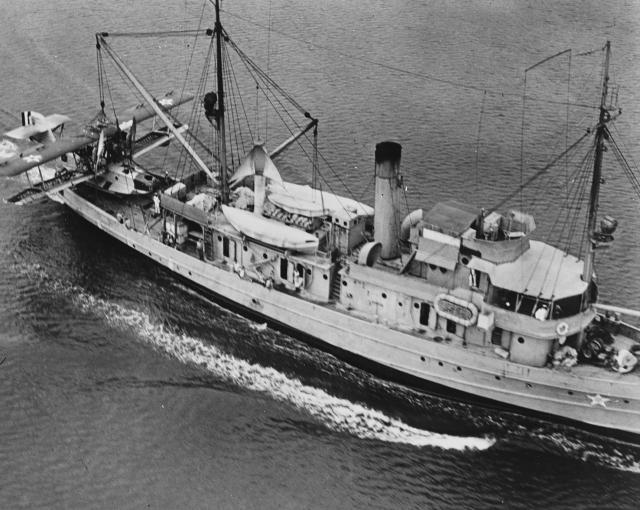

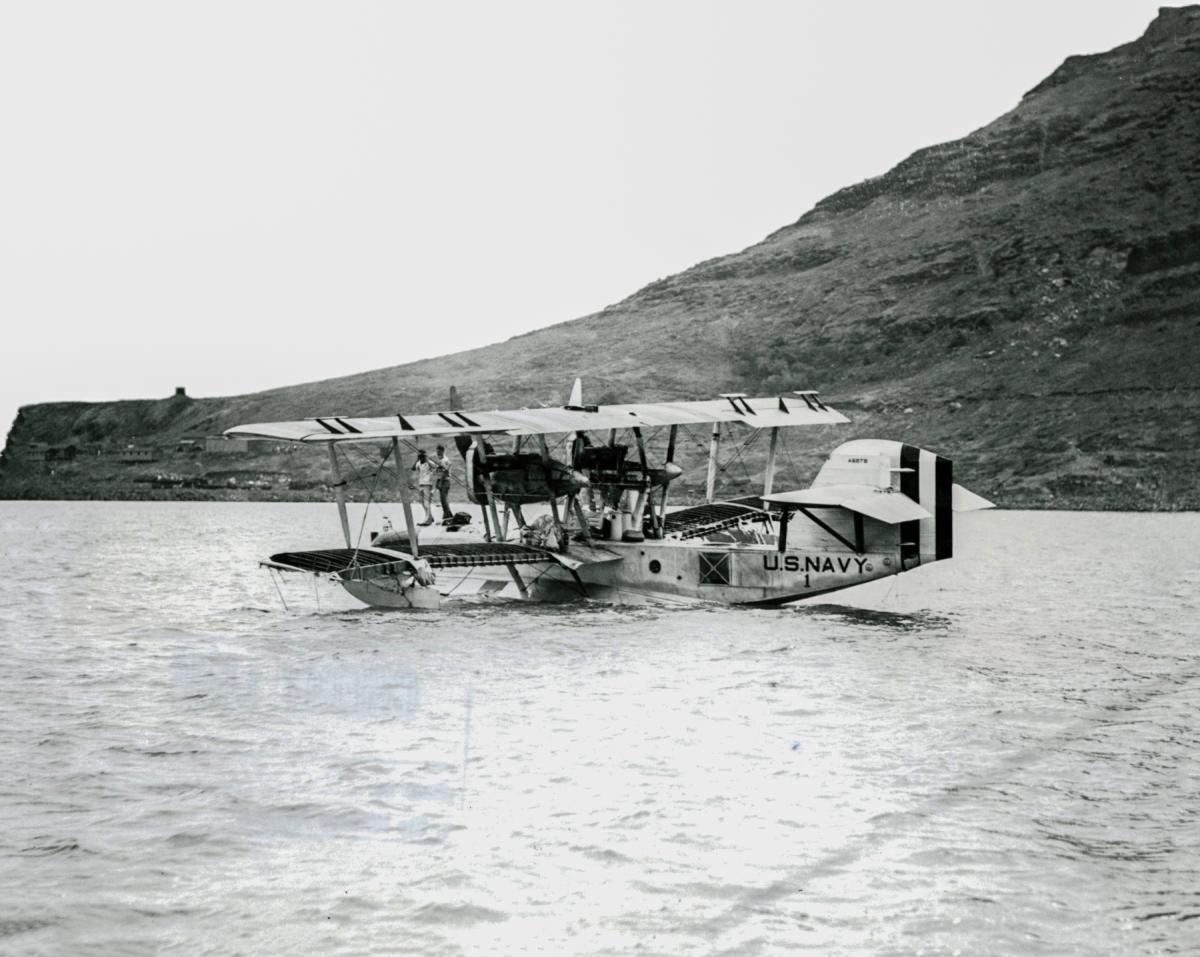

The Navy’s West Coast–Hawaii Flight of 1925 had been planned for at least three years and originally was slated to include three flying boats: the pair of PN-9s built in the Navy’s Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia (“P” standing for “patrol,” “N” for “Navy”) as well as the PB-1, a Boeing-built flying boat with two propellers mounted back-to-back in opposite directions atop the plane, with one motor pushing and one pulling (“P” for “patrol,” “B” for “Boeing”). Mechanical problems on board PB-1 caused it to be dropped from the Navy’s flight plan.

That left the two PN-9s, which were more or less 49-foot-long biplanes melded onto metal boat hulls. Across each fuselage was mounted a pair of 70-foot-long, fabric-covered, wooden wings, and between the upper and lower wings was a pair of 500-horsepower Packard engines, each spinning propellers 13 feet long. Big, heavy, and slow, with an average speed of 70 miles per hour, the PN-9s were the Navy’s most modern flying boat.

But modern did not mean perfect. As Rodgers and his crew on board PN-9 No. 1 flew west toward the islands, they soon lost sight of their sister flying boat. Hours later they received bad news via radio: PN-9 No. 3 was down at sea. Fortunately, the flying boat—which became disabled from a broken oil line—was recovered by a Navy destroyer, one of the dozen or so guard vessels spread out in a line along the flight path from San Francisco to Hawaii. Stationed 200 miles apart, each guard vessel was charged with providing smoke or spotlight signals to the aviators approaching in the flying boats. Then, when the flying boats had passed, the destroyers were to steam after the aircraft in case of an emergency. In the case of PN-9 No. 3, such a plan worked exactly as envisioned, with the destroyer USS William Jones (DD-308) picking up the stranded aircraft and its five-man crew, all of whom had survived a harrowing sea landing made with no working engine.

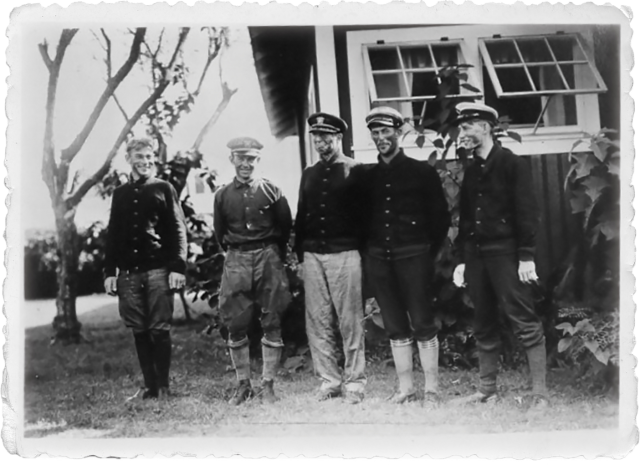

On board PN-9 No. 1, the crew could do little but concentrate on their own flight as they learned of their sister plane’s distress from reports received by Chief Radioman Otis G. Stantz. Situated in the tail of the plane, the 26 year old from Indiana was responsible for two main pieces of equipment. The first, a radio receiver, was a battery-powered device that allowed PN-9 No. 1 to hear messages from nearby ships and stations on shore. The other, a transmitter powered by an air turbine mounted outside the plane, allowed the flying boat to send radio messages, such as Stantz’s midnight communication made ten hours into the flight: “EVERYTHING OK FEELING FINE ALL OF US.”1

Beyond Stantz, Rodgers’ crew was rounded out by Lieutenant Byron J. Connell, 31, of Pennsylvania; Chief Machinist’s Mate Skiles Pope, 30, of Tennessee; and Aviation Machinist’s Mate William M. Bowlin, another 26-year-old Hoosier. All the men save Stantz were qualified as pilots, though Connell so far had occupied the controls for most of the flight while Stantz manned the radio and Pope and Bowlin tended to the engines and fuel supply, the latter of which was spread out among nearly a dozen large tanks. Commander Rodgers, 44, who tasked himself with navigational duties, spent most of the flight occupying the navigator’s cockpit in the nose of the flying boat.

Extreme vigilance was required of any navigator for a flight to Hawaii. Any error greater than three degrees could doom a flight leaving from San Francisco, as aviators would never spot the remote and tiny islands they hoped to reach. Rodgers’ crew, however, had full faith in “Navigatin’ John,” as did the Navy. For as long as there had been a U.S. Navy, there had been a John Rodgers prominent within its ranks, beginning in 1798 when President John Adams appointed Rodgers’ great-grandfather and namesake a second lieutenant on board the USS Constellation. This Rodgers, who served heroically during the War of 1812, would be the first of many Rodgers men to achieve the rank of commodore or rear admiral in the U.S. Navy.

To Commander John Rodgers’ satisfaction, PN-9 No. 1 had navigated its transpacific route perfectly so far, spotting every guard vessel along the line. When winds buffeted the plane, pushing it north or south, Rodgers took measurements with smoke bombs, drift meters, or a sextant, then issued course corrections to compensate for unintended changes in direction. But when these winds shifted to become a westerly headwind, Rodgers could only sigh. Already their fuel situation was precarious, the plane holding just enough gasoline to reach the islands so long as a predicted tailwind was encountered. But a significant and sustained headwind meant their airspeed would be retarded severely, putting the success of the nonstop flight in jeopardy.

As PN-9 No. 1 flew through the night and the next morning, the flying boat encountered hour after hour of headwind, forcing Rodgers to conclude the plane’s fuel supply would not last. Knowing PN-9 No. 1 soon would be approaching the USS Aroostook (CM-3), an aircraft tender positioned 400 miles from Hawaii and one of the last ships on the Navy guard line, Rodgers made the decision to rendezvous with the ship, touch down on the ocean, and refuel. Then PN-9 No. 1 could take off from the sea and complete the first flight to Hawaii, though not the first nonstop flight. Unfortunately, PN-9 No. 1 never found the Aroostook. Approaching the aircraft tender in a squall that severely limited visibility, the flying boat’s crew was hampered further by their reliance on inaccurate radio bearings transmitted by the Aroostook. After having cruised comfortably for approximately 24 hours, finding every guard vessel along the flight path, the crew of PN-9 No. 1 became desperate in their search for the Aroostook, which continued to elude them. Gasoline had become scarce, with Pope and Bowlin attempting to prolong flying time by using sponges to mop up any little bit of fuel that might have spilled out of tanks into the bilge.

“PLANE VERY LOW ON GASOLINE AND DOUBT ABILITY TO REACH DESTINATION. KEEP CAREFUL LOOKOUT . . .” radioed Stantz. “WE WILL CRACK UP IF WE HAVE TO LAND IN THIS ROUGH SEA WITHOUT MOTIVE POWER.”2

At about 1615, the gas finally gave out and the plane’s engines stopped in midair. Connell quickly turned into the wind and made a rough emergency landing atop the waves. The crew, however, hardly cared they were alive; each was sick over their failure to make the nonstop flight. So disappointed was the crew that no one spoke following their ocean landing. Instead, they wordlessly retreated to their own areas of the plane, snacking and sipping on the oranges and coffee that remained from their dwindling rations. They would be content to wait in silence, they seemed to have decided, until the Aroostook came along with more fuel.

Radio reports, however, soon indicated there would be no imminent refueling, or rescue. The communications overheard by Stantz through his battery-powered receiver made clear that the Navy had no idea where to find PN-9 No. 1. And to Stantz’s great frustration, he no longer could respond to the searching Navy vessels and clue them in to their position. Since his transmitter was powered by an air turbine, the radio could send messages only when PN-9 No. 1 was flying. The predicament led Stantz to cry tears of anger as he tried unsuccessfully—again and again—to broadcast a message. “We were listening all the time what was being said about us,” said Stantz. “We were only sorry we couldn’t answer back.”3

When it became clear no one was coming to the rescue, the Navy men decided to save themselves. And if they couldn’t fly their flying boat to Hawaii, then they would sail it to the islands. Removing swaths of fabric from the lower wing, the crew strung up the dope-covered cloth between the biplane’s wings, creating a makeshift sail. Then Rodgers and his men continued their journey to Hawaii under sail power, able to tack just a few degrees off the wind and cruise at a steady speed of two or three knots.

Despite this innovation, many hardships lay in store for the men, who were still 450 miles from Hawaii. The few sand sharks that began trailing their plane had grown in a few days’ time into a large and unnerving school joined by barracuda. When two fierce-looking 14-foot tiger sharks joined the mob, Bowlin became nervous. The “big black fellows” were “always waiting,” said Bowlin, “I guess for a choice bit of human flesh.”4

Yet Rodgers was unmoved by their stalking. The commander had made it his habit each morning to crouch down, place his head close to the water, and warn the dorsal fins cutting through the waves, “Not today, mister, not today.”5

As days passed, the crew’s rations, minimal to begin with, were almost fully consumed, leaving the famished men to search the bilge for orange rinds and sandwich crusts they had thoughtlessly tossed aside days before. At one point, Rodgers caught a small flying fish and, while stroking it tenderly, offered pieces to his crew. They declined, leaving Rodgers to swallow the live fish down in one satisfying gulp.

Fresh water was scarce and rationed strictly by Rodgers for fear the men’s voyage could be a long one. When it rained, the men rushed outside the plane to catch water in buckets and their open mouths, licking the surfaces of the flying boat to lap up remaining droplets. Later, they collected rainwater on the slick, painted wing fabric they tore from the flying boat, not caring that the aluminum-impregnated paint made it the most “slippery” water they had ever drank.6

A few times the crew spied other ships on the horizon, but the vessels never saw the small flying boat in return. Toughest of all was the news heard via radio that the Navy was beginning to lose faith that the crew of PN-9 No. 1 would be found. After launching a huge search near Hawaii that involved at least 26 destroyers, 34 planes, and 9 submarines searching more than 70,000 square miles, naval officers began doubting the flying boat had survived its sea landing. In a heartbreaking radio communication that was overheard by Rodgers and his crew, 21 pilots on board the carrier USS Langley (CV-1) stated they “CONCUR THE PLANE HAS SUNK AND THE SEARCH SHOULD BE DISCONTINUED.”7

Rodgers, in an admirable display of leadership and courage, brushed off each of these struggles and disappointments. “Hell, boys, we might be worse off than this,” the commander told his crew. “Why I once knew a man who was adrift for 15 days with nothing but a log under him!”8

The crew’s spirits may have been relatively high on board the flying boat, but by the eighth day at sea the men’s strength was sapped, leaving the dehydrated aviators to crawl about the flying boat as they attended to duties. According to Navigatin’ John, the floating aircraft still was en route to Hawaii, likely to be swept by the current to either Oahu or Kauai—two islands separated by a 72-mile channel. To improve their chances of reaching at least one of the islands, Connell rigged together a keel from metal floorboards, lashing it perpendicular to the flying boat’s hull. This allowed the boat to tack a full 15 degrees off the wind. Rodgers commended the lieutenant’s innovation but also asked teasingly why Connell had not thought to make the keel any earlier.

The next day Oahu was spied in the distance, but its shore loomed too far to make a break across the channel. The sailors then reluctantly steered for Kauai, still unseen. This would be their last chance. If they missed Kauai, they would be swept farther into the Pacific, past the Hawaiian Islands, into an oceanic no-man’s land where they almost certainly would perish.

On the tenth day at sea, Kauai appeared in the distance, much to the crew’s relief. The day was spent steering the awkward flying boat toward shore, but by late afternoon PN-9 No. 1 still sat off the beach, separated from Kauai’s few bays by treacherous coral reefs. Rodgers did not want to cross these reefs with dusk approaching, yet he also did not want to be swept away from the island at night, possibly losing their only chance for a landing. Before Rodgers agonized too much over the decision, a submarine surfaced behind the flying boat, surprising the aviators. She was R-4, part of a Navy submarine guard line stretched across the channel between Oahu and Kauai. Wary of making an erroneous sighting, R-4 signaled to the flying boat: “WHAT PLANE IS THAT?”9

The flying boat signaled back immediately: “PN-9 NO. 1 FROM SAN FRANCISCO.”

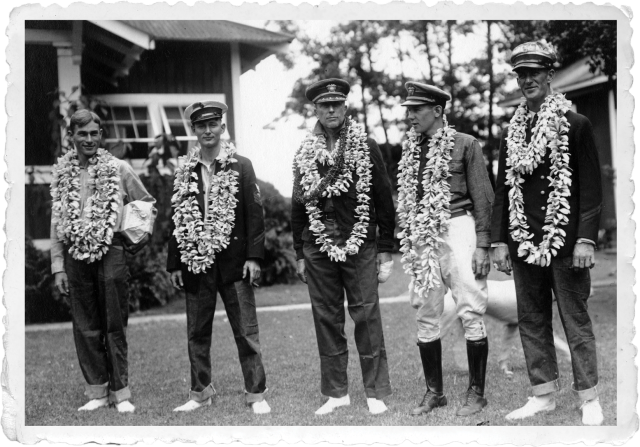

That night, R-4 helped tow the flying boat into Kauai’s Nawiliwili Harbor, where locals cheered from the beach. By this time radio reports had been sent to Honolulu and reached the mainland United States, too, announcing the miraculous survival and rescue of Rodgers and his men. Residents of Honolulu were ecstatic over the news, dancing in streets and preparing for a massive celebration.

As Rodgers was transported to Oahu from Kauai on board the USS MacDonough (DD-331), he spoke of his regret for the flight’s failure. His fellow officers immediately admonished him, replying that the flight and voyage of PN-9 No. 1 was one of the greatest expeditions in both Navy and aviation history. This opinion was not unique. As Honolulu Advertiser journalist Charles Edward Hogue noted, Rodgers and his crew displayed the “indomitable spirit of the US Navy” during their ten hard days lost at sea. “Landsmen wavered between hope and despair during those days: old salts shook their heads dubiously, and shorestaying officialdom feared the worst,” wrote Hogue. “But the Navy itself held fast: surrender is a word missing from its vocabulary.”10

1. U.S. Navy West Coast-Hawaii Flight Report, 1925, National Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, Florida.

2. U.S. Navy West Coast-Hawaii Flight Report.

3. “Roaring Avalanche of Enthusiasm for Heroes of the Navy,” Honolulu Advertiser, uncertain date.

4. Ray Coll Jr., “Sinister Escort of Sharks Follows in Wake of Helpless Plane,” Honolulu Advertiser, uncertain date.

5. “Pacific Sharks Called Hazard for Amelia,” San Francisco Examiner, 8 July 1937.

6. “Lack of Water, Tobacco, Most Keenly Felt While Fliers Drifted at Sea,” Honolulu Advertiser, 11 September 1925.

7. William J. Horvat, Above the Pacific (Fallbrook, CA: Aero, 1966), 57.

8. Coll, “Sinister Escort of Sharks Follows in Wake of Helpless Plane.”

9. Byron J. Connell, “Lieut. Connell Tells Desperate Plight of Pacific Fliers,” New York Times, 24 September 1925.

10. Charles Edward Hogue, “Epic Story of Flight and Disaster, Hope and Black Despair Ends as in Romance,” Honolulu Advertiser, uncertain date.