The 17th century witnessed an intense maritime rivalry between the Dutch Republic and England. The former, its independence from Spain only recently affirmed, possessed a massive merchant marine engaged in lucrative worldwide trade and held far-flung colonies governed by armed, publicly traded companies acting on behalf of both the republic and their shareholders. England, too, possessed a sizeable merchant fleet and overseas territories governed by profit-seeking corporate entities. In 1652, the often-violent trade competition between the two nations led to the outbreak of the First Anglo-Dutch War, a primarily naval conflict in which England was victorious.1 However, the 1654 Treaty of Westminster, which officially ended the war, left many of its causes unresolved.2

Anglo-Dutch Proxy War

Friction between the Dutch Republic and England continued over the next decade. England’s desire to acquire additional colonies and secure new markets required the elimination of the Dutch Republic as a trade rival, and some in England viewed the influence of the “religiously pluralist and politically republican” Dutch as an ideological threat partially to blame for the recent English Civil War.3 In addition, peace between England and the Dutch Republic did not prevent English joint-stock companies from pursuing their own international objectives. Forces equipped by these firms soon came into direct conflict with their Dutch counterparts.4

When the Dutch barred English ships from loading cargo at Indian ports, private English forces responded by constructing forts in the Gambia to serve as bases for operations against Dutch outposts and trade routes. Dutch traders retaliated by attacking English trading posts and capturing several English merchant ships.5 As the proxy war between the trading companies developed, England updated and reaffirmed the Navigation Act of 1651, an effort to prevent Dutch shipping from participating in English trade.6

In 1664, English forces, though still technically at peace with the republic, captured the Dutch colonies of New Netherland, which was renamed New York, and St. Eustatius. In response, Lieutenant Admiral Michiel de Ruyter led Dutch naval forces in attacks on English maritime trade and colonies. With tensions growing, English merchants and political leaders pressed for Dutch trade concessions. Two of the key leaders favoring a hard line were Sir George Downing, King Charles II’s envoy to the republic; and Charles’ brother, the Duke of York, who was England’s Lord High Admiral and the future King James II.7

Downing believed the Dutch would be unwilling to go to war with England so soon after the First Anglo-Dutch War and therefore would accept English demands without a fight.8 However, he failed to account for significant Dutch reforms over the preceding decade that allowed the republic to reorganize its finances and reestablish credit. Dutch naval changes over the same period led to more efficient shipbuilding practices, an improved supply and rationing system, and an increase in the professionalism of the Dutch officer corps. The result was a larger, more capable Dutch fleet.9

Thus armed, the Dutch Republic resisted mounting English pressure. Dutch leaders believed that England would be unable to fund a war, and that English belligerence was therefore a bluff. Meanwhile, London’s calls for concessions became calls for war.10 King Charles also may have had his own reasons for desiring war. He had returned from exile only four years earlier, when the English monarchy was restored. The French ambassador to England theorized that Charles hoped a successful war with the Dutch would strengthen his hold on the English throne by winning the loyalty of Parliament and demonstrating to other European countries that he was firmly in control. The King came closer to achieving this goal when, on 21 April 1664, the House of Commons passed a resolution that proclaimed its total support for the monarch in any actions he might take against the Dutch.11 Finally, on 4 March 1665, England declared war.12

Conflict and Economic Crisis

At the outset, the English intended to draw the Dutch fleet out to sea and destroy it, rapidly securing favorable peace terms.13However, despite a decisive English victory at Lowestoft, the conflict’s first naval battle, fighting continued for two years. The Dutch fleet proved a more capable foe than the English had expected, and neither side was able to secure a clear advantage. By early 1667, England’s finances were exhausted, the country no longer could afford to keep its warships deployed, and much of the fleet was laid up. The English hoped that the resulting surplus of sailors would provide manpower for merchant ships that could then work the trade routes, putting an end to England’s economic woes.14

By March 1667, the economic situation had become so dire that English sailors were not receiving pay. Famed English diarist Samuel Pepys, a member of the Royal Navy Board, complained that navy crews were refusing to sail because they thought it unlikely that their government would ever pay them for their services. The workers and sailors had been paid only in IOUs, called “tickets,” for months and refused to work until they were properly compensated.15

Its position weakened, England entered into peace talks with the republic at the southern Dutch city of Breda. Though England’s situation was unfavorable, its representatives made demands that the republic was unwilling to accept, and the talks stalled. As word of England’s financial straits and lack of naval preparedness spread, the Dutch saw an opportunity to strike their weakened opponent to secure better terms for peace. A successful attack also would bring a speedy end to the negotiations, allowing the Dutch to focus on countering French military incursions.16 The Dutch fleet was dispatched to “attempt an enterprise against the ports, cities, and strong points of the enemy.”17

Dutch Arrival off England

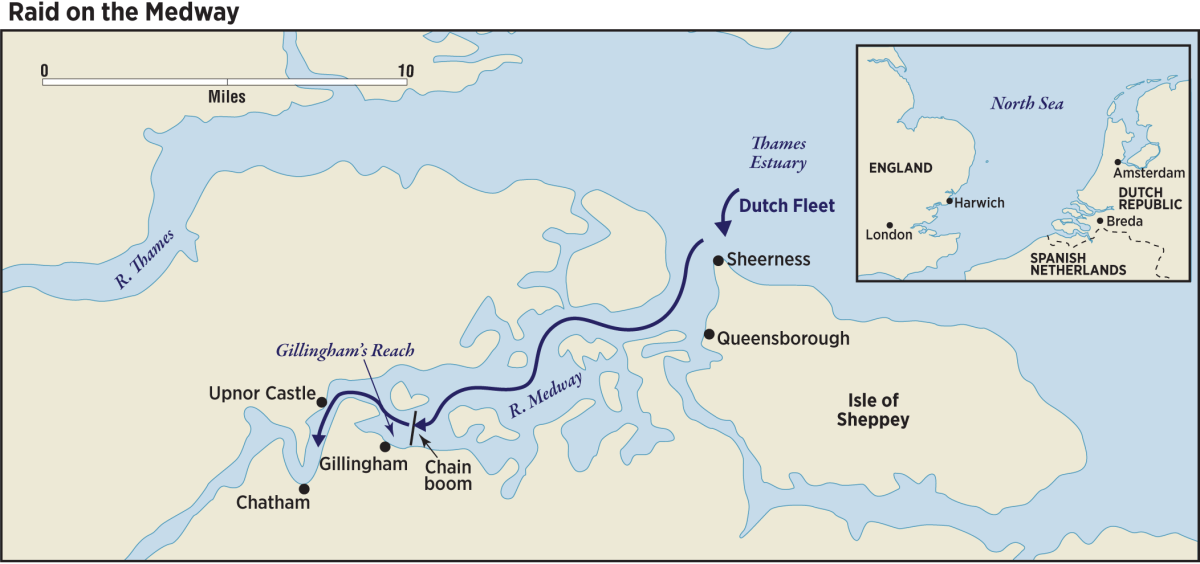

By 27 May 1667, Dutch warships and transports had rendezvoused under the command of de Ruyter. When the entire fleet was assembled, the admiral commanded 64 ships-of-the-line and frigates, 15 fireships, and 20 smaller warships, crewed by 17,500 sailors and marines.18 The fleet departed for the Thames Estuary.

Two months earlier, as the Royal Navy was laid up, Pepys had voiced his concern regarding England’s vulnerability, commenting that it was very possible the Dutch would exploit the English Navy’s absence by blockading the mouth of the Thames or the Medway. In fact, such an eventuality was a common fear among English merchant crews.19 When on 9 June the Dutch fleet was sighted off Harwich, near the Thames Estuary, Pepys’ worst fears were realized, and the local English militia was hastily mobilized to repel a possible enemy landing.20

A number of nobles also sensed an opportunity for battlefield glory and set off to join the militia gathering at Harwich. As Pepys later remarked, it was all “to little purpose, I fear, but to debauch the country women thereabouts.” Meanwhile, Pepys was flooded with requests for resources to prepare a naval defense against the approaching enemy fleet. To his frustration, he could do little because of the government’s lack of funds.21

Once off the mouth of the Thames, the Dutch fleet paused while it was reorganized and its commanders planned an attack. De Ruyter sent one of his subordinates, Lieutenant Admiral Willem Joseph van Ghent, to capture the island of Sheppey and the fortifications at Queensborough and Sheerness as well as their large stores of military and naval supplies. Van Ghent’s attack was successful, and the supplies the Dutch could not take with them they destroyed.22

As panic gripped London, English Admiral George Monck was ordered to Chatham Dockyard on the River Medway to organize the naval facility’s defenses and move several of the recently mothballed warships in the river at Gillingham’s Reach farther upriver and out of danger. What he found at Chatham appalled him. Of 1,100 dockyard workers and sailors, only three initially were willing to assist in preparing the defenses. Many fled on hearing of the Dutch approach, taking whatever tools or supplies of value they could carry.23

Despite the bleak situation, a 14½-ton iron chain “boom” stretching across the Medway at Gillingham’s Reach blocked the path of enemy ships, and Monck organized land forces and batteries along the river and had ten ships scuttled in the channel. The shortage of dockyard labor meant any ships that were not scuttled were left moored in the river or in the yards.24

Chaos on the Medway

On 12 June, the Dutch arrived in Gillingham’s Reach and sent several ships to break the chain. The Dutch vessels succeeded not only in breaching the barrier, but also in capturing or destroying several nearby English warships.25 Navigating around the ten blockships, other Dutch ships destroyed or captured the remaining enemy warships the English themselves had not sunk. One of the captured vessels was the HMS Royal Charles, a three-deck, 80-gun ship-of-the-line. Her skeleton crew fled, and the ship allegedly was captured by just nine Dutch sailors.26

While the Dutch attacked the English ships on the Medway, the English—Pepys included—frantically tried to organize an effective defense. Most sailors and yard workers refused to take part in any efforts against the Dutch until their tickets were paid by the navy, so Pepys secured a sizeable amount of cash to pay them in full. However, because of the government’s poor record compensating them, most of the sailors and workers Pepys attempted to pay refused to believe he had any cash readily available, instead assuming that it was a trick. The problem persisted when Pepys attempted to press merchant ships into service; he often was met by distrustful crews. Meanwhile, the panicked, uncoordinated efforts of various government officials to defend London resulted in ships being scuttled at Blackwall and Woolwich, just east of the city, out of fear that the Dutch next would attempt to sail up the Thames.27 Many of these vessels, however, contained crucial supplies or were fireships intended for use against the Dutch.28

On 13 June, the Dutch made a final attack up the Medway, destroying three ships of 76, 82, and 90 guns and a number of shore batteries. By this time, more English militia was pouring into the area, prompting the Dutch to return to the Thames Estuary. After five wildly successful days, the “deepest insult that perhaps [England] has sustained since the Norman invasion,” as one historian described it, was finally over.29 In all, the Dutch had lost between 50 and 150 men, while the English had suffered no fewer than 500 casualties and the capture or destruction of at least 12 major warships and numerous other vessels, as well as shore batteries, fortifications, and naval and military supplies.30

Unrest and Scapegoats

With the arrival of reinforcements and the addition of captured vessels, de Ruyter’s fleet swelled to more than 100 warships. This powerful force blocked traffic from the Thames and Medway to the open sea.31

The blockade dealt a heavy blow to the already ailing English economy. This combined with the demoralizing defeat on the Medway and the fear of Dutch invasion led to unrest. Pepys describes one incident in which the wives of unpaid sailors took to London’s streets, chanting, “This comes of your not paying our husbands!” As a naval administrator, Pepys feared for his safety—he was convinced that if the mob did not kill him, the King, in his inevitable search for scapegoats, might. He sent his wife and father into the country; distributed his money, writings, and other valuables among his friends for safekeeping; and wrote his will.32

The situation in London grew more unstable as sailors flooded into the city demanding that their tickets be paid. Confidence in King Charles was shaken, a dangerous problem for a monarch so recently returned from exile. More ships were added to those already scuttled in anticipation of yet another Dutch incursion, but beyond such desperate defensive measures, the English government had few options.33 It lacked the funds and now even the ships to launch a counterattack, and its sailors refused to risk their lives for a government that paid them in IOUs.

The hunt for scapegoats began, and Chatham Dockyard Commissioner Peter Pett was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Pepys assumed he would be next but managed to avoid blame for the disaster.34He was busy enough trying to appease the irate, unpaid sailors descending on London, a job that became even more complicated when Pepys realized that a number of officers were cashing tickets they had purchased from their desperate subordinates at reduced prices or had stolen from their sailors outright. Some even tried to cash the pay tickets of their dead sailors.35

A Fragile Peace

King Charles considered breaking off the peace talks at Breda in response to the Dutch attack, but England was in no position to continue the war—public sentiment now ran as strongly against the King as it did against the Dutch.36 As if to reemphasize their military advantage, the Dutch landed 1,600 marines and sailors at Harwich on 2 July. Though the force was successfully repulsed, it was clear the Dutch still held the initiative. They could sail freely along England’s coast, launching raids as they pleased, while the English could do nothing but mobilize militia to fend off the landings.37

Finally, King Charles instructed the English representatives at Breda to drop many of their demands. The resulting peace treaty was signed just days later, on 21 July 1667.38 None of England’s goals had been achieved in the conflict. Among the few significant territorial changes affirmed by the treaty were the prewar English capture of New Netherland and the Dutch retention of Surinam.39

The Dutch Raid on the Medway stole from England the opportunity to secure favorable peace terms. Though the Treaty of Breda did not result in any loss of territory for England, the loss of prestige and the loss of confidence in King Charles II caused by the Medway raid were nearly as damaging and a source of embarrassment for years to come. However, the rivalry left unresolved by the First Anglo-Dutch War ultimately was left unresolved by the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Animosity between England and the Dutch Republic would persist after the Treaty of Breda, eventually leading to the Third Anglo-Dutch War only five years later.

1. Michael A. Palmer, “‘The Soul’s Right Hand’: Command and Control in the Age of Fighting Sail, 1652–1827,” The Journal of Military History 61, no. 4 (October 1997), www.jstor.org/stable/2954082, 679, 681.

2. Paul Seward, “The House of Commons Committee of Trade and the Origins of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, 1664,” The Historical Journal 30, no. 2 (June 1987), www.jstor.org/stable/26939202, 438.

3. J. R. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century (New York: Longman Publishing, 1996), 146; Stephen C. A. Pincus, “Popery, Trade and Universal Monarchy: The Ideological Context of the Outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War,” The English Historical Review, no. 422 (January 1992), www.jstor.org/stable/575674, 2.

4. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 145.

5. Seward, “The House of Commons,” 439–40.

6. Palmer, “‘The Soul’s Right Hand,’” 438.

7. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 150–51; 145–46.

8. Jones, 145.

9. Alvin D. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion of England: 1667,” Military Affairs 13, no. 4 (Winter 1949), www.jstor.org/stable/1982741, 223.

10. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 147–49; 145–48.

11. Pincus, “Property, Trade and Universal Monarchy,” 3, 1.

12. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 156.

13. Jones, 155.

14. Jones, 174–75.

15. Robert Latham, ed., Samuel Pepys and the Second Dutch War: Pepys’s Navy White Book and Brooke House Papers (Aldershot: Scholars’ Press, 1995), 134; Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 174–75.

16. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 224–26; Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 175.

17. Coox, 226.

18. Coox, 226.

19. Samuel Pepys, Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, F.R.S, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: John D. Morris & Company, 1906), 134.

20. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 228.

21. Pepys, Diary and Correspondence, 145.

22. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 228.

23. Coox, 229; Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 177.

24. Coox, 229.

25. Coox, 229; Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 177.

26. Coox, 229.

27. Pepys, Diary and Correspondence, 146, 147, 154; Charles R. Low, The Great Battles of the British Navy (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1872), 63.

28. Pepys, Diary and Correspondence, 157.

29. Low, The Great Battles, 62.

30. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 229.

31. Coox, 230.

32. Pepys, Diary and Correspondence, 150–54.

33. Pepys, 154; Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 177; Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 231.

34. Coox, 160–61.

35. Latham, ed., Samuel Pepys, 263.

36. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, 178.

37. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 231–32.

38. Low, The Great Battles, 63.

39. Coox, “The Dutch Invasion,” 231–33.