The U.S. Navy’s Yangtze Patrol was a strange sea creature: a naval force with trifling combat power but appreciable heft as a constabulary and diplomatic force. “YangPat” was gunboat diplomacy made manifest. The Navy formally instituted the Yangtze River flotilla a century ago, on 25 December 1919, but its origins run much deeper into the past.

U.S. “River Rats” had been doing their best to defend American lives, interests, and property in China for decades by 1919, even as tumult engulfed—and ultimately brought down—the Celestial Empire. In his history of the patrol, Rear Admiral Kemp Tolley, a one-time gunboat executive officer and self-proclaimed River Rat, dates the flotilla’s inception to 1854, when the sidewheel steam frigate Susquehanna became the first U.S. Navy man-of-war to foray up the Yangtze.1

Trying to manage unrest in turbulent surroundings, then, was nothing new for those sent to ply China’s internal waterways. The gunboat flotilla was a subsidiary arm of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, itself an offbeat naval force in that it reported directly to the Navy Department in Washington, D.C., rather than to the operational commander-in-chief of the U.S. Fleet.2 The unusual working arrangement lent the U.S. State Department an outsized voice in Asiatic Fleet and YangPat operations.3

That foreign policy prelates should have a direct say in naval operations was fitting. After all, River Rats were naval diplomats in the truest sense. As the Navy Department’s annual report for 1921 explained, the Asiatic Fleet commander oftentimes was called on to make “momentous decisions,” acting as “the Nation’s representative, in a manner not purely naval.” The Yangtze Patrol was entrusted with acting “for the protection of Americans and foreigners generally in the disturbed regions of South China and the valley of the Yangtze River.” YangPat crews, concluded the report, were “constantly involved in preventing strife and protecting persons and interests in case strife begins. They operate in areas where there is no peace” (emphasis added).4

There was no peace, but neither was there open war. YangPat bestrode what present-day commentators call the “gray zone,” that shadowland where peace blurs into war.5 Nor was the “enemy” confronting U.S. seafarers a peer armed force. Seismic changes had befallen China and the world since midcentury. The Qing Dynasty, China’s last, progressively had lost its sovereign grip on the country and with it the authorities’ monopoly on the legitimate use of force within China’s frontiers, even as imperial powers encroached on the country.

Unable to keep order, dynastic rulers watched helplessly as local armies wrangled for control over the countryside, an opium syndicate flourished, and brigandage ran amok in the Yangtze Valley, along with most of China. YangPat crews might face off against a different scourge on any given day. With no single foe to prepare for, and with radio communications in their infancy, gunboat skippers—like their fleet boss—enjoyed uncommon liberty to manage situations as they found them. Their superiors ratified their actions—or not—after the fact.

By 1854, when the Susquehanna’s cruise announced the Navy’s arrival on the Yangtze, the Qing Dynasty was reaping the bitter fruit of waterborne unpreparedness. It had lost one “Opium War” to European conquerors shortly before and was destined to lose another shortly after. The Dragon Throne lost control of access to the country in the process. The victors foisted a series of “unequal treaties” on China that wrested away territories such as Hong Kong while granting foreign warships extensive rights to patrol the Yangtze and other internal waterways.

Crudely speaking, the “Great River” bisects China into northern and southern halves while permitting shallow-draft vessels to voyage inland as far as 1,700 miles from the sea.6 As Alfred Thayer Mahan teaches, navigable rivers are a blessing in that they connect the continental backcountry with the high seas, and thence to foreign seaports, and thus cut the transaction costs associated with seagoing trade. But they are a curse for countries without defenses adequate to fend off oceanic invaders.7 This was imperial China’s plight in 1854. By the early 20th century, the Qing Dynasty tottered on the brink of collapse.

The last emperor fell in 1911. Three years later, when World War I erupted in Europe, European navies evacuated the Far East to fight elsewhere or were interned in the region. That left YangPat—generally the weakest of the foreign gunboat flotillas, measured by tonnage—standing alone as the guardian of Western interests along the river. Imperial Japan was free to exploit the ensuing power vacuum. Tokyo issued “Twenty-one Demands” to China in 1915 in a bid to make the continental giant its vassal state. European imperial powers returned to East Asia after World War I to find regional warlords battling for territory, resources, and political clout. Fighting was commonplace among warlord armies encamped along the northern and southern banks of the Yangtze.

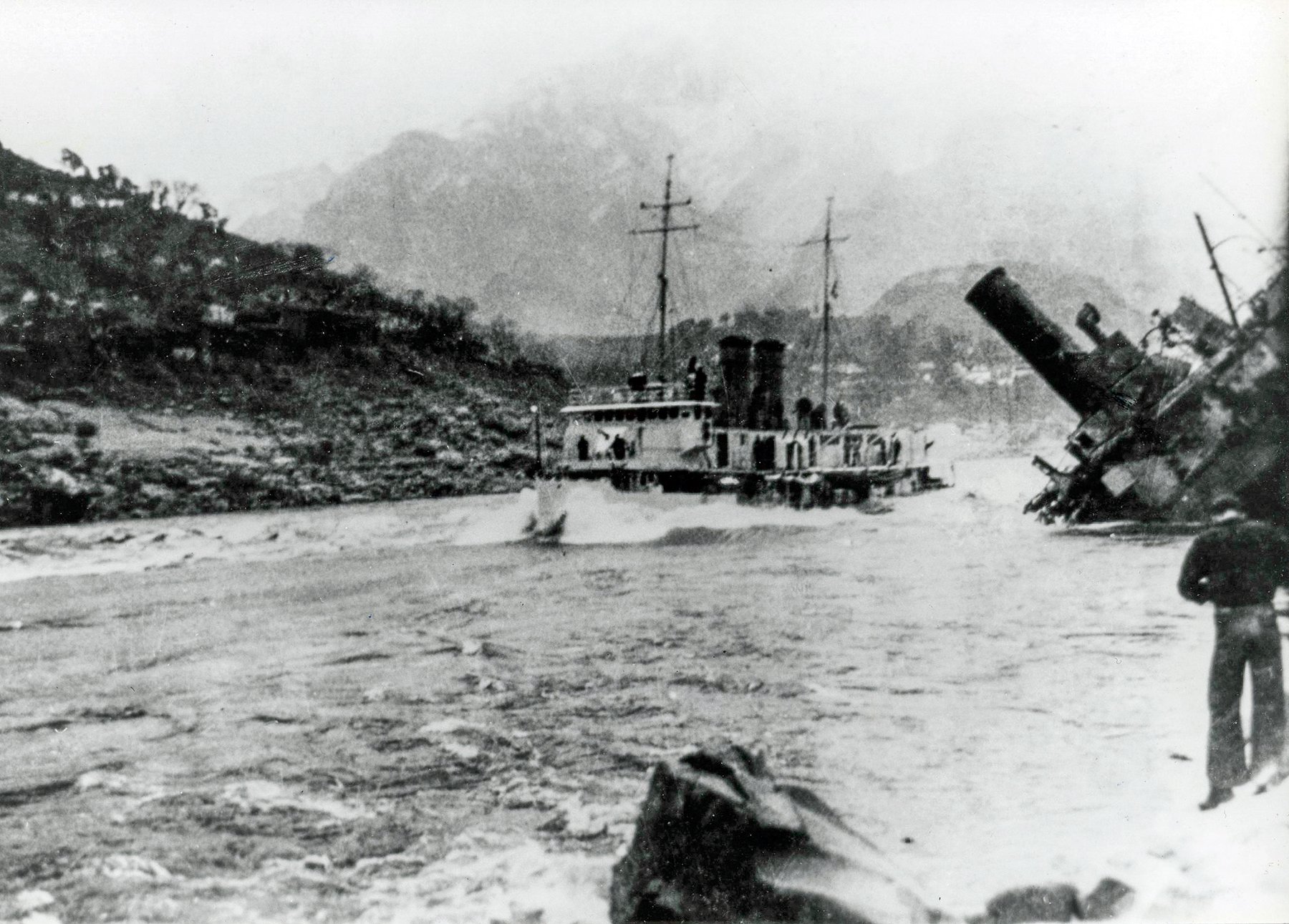

Disunity, internal strife, predatory neighbors circling around looking for advantage—this was the operating environment surrounding the Yangtze Patrol when it officially entered service late in 1919. Things scarcely had improved by 1937, when Japanese warplanes sank the USS Panay (PR-5) near Nanking, or by 1941, when the Roosevelt administration disbanded YangPat on the eve of the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor. In short, an exceptionally slender force struggled to cope with exceptionally trying circumstances. It is worth asking how such a ragtag fleet could succeed at constabulary work, and what traits allowed officers and enlisted men to excel in times of violent peace.

The Navy’s Not-So-Big Stick

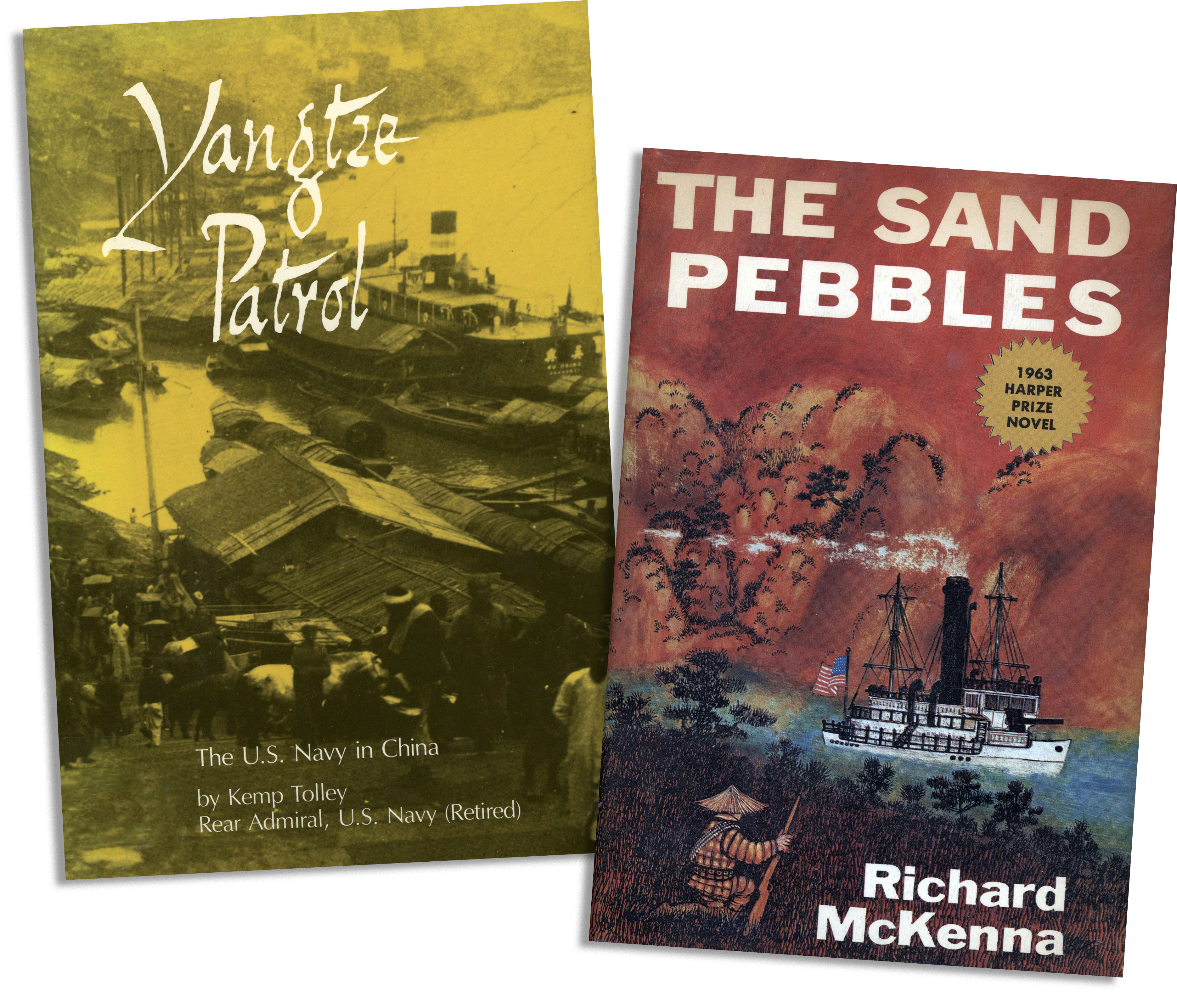

The Yangtze Patrol was not President Theodore Roosevelt’s “Big Stick”—a fleet exuding such power and majesty that it overawes foreign observers. It intimidated few. Sailor-scribe Richard McKenna, who served as an enlisted engineer on the Asiatic Station and won acclaim for his novel The Sand Pebbles, paints a vivid portrait of the strategic setting during the mid-1920s.8 At that time, warlordism was giving way to full-blown civil war between Mao Zedong’s Red Army and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army—a conflict that would drag on intermittently until the communists’ 1949 victory.

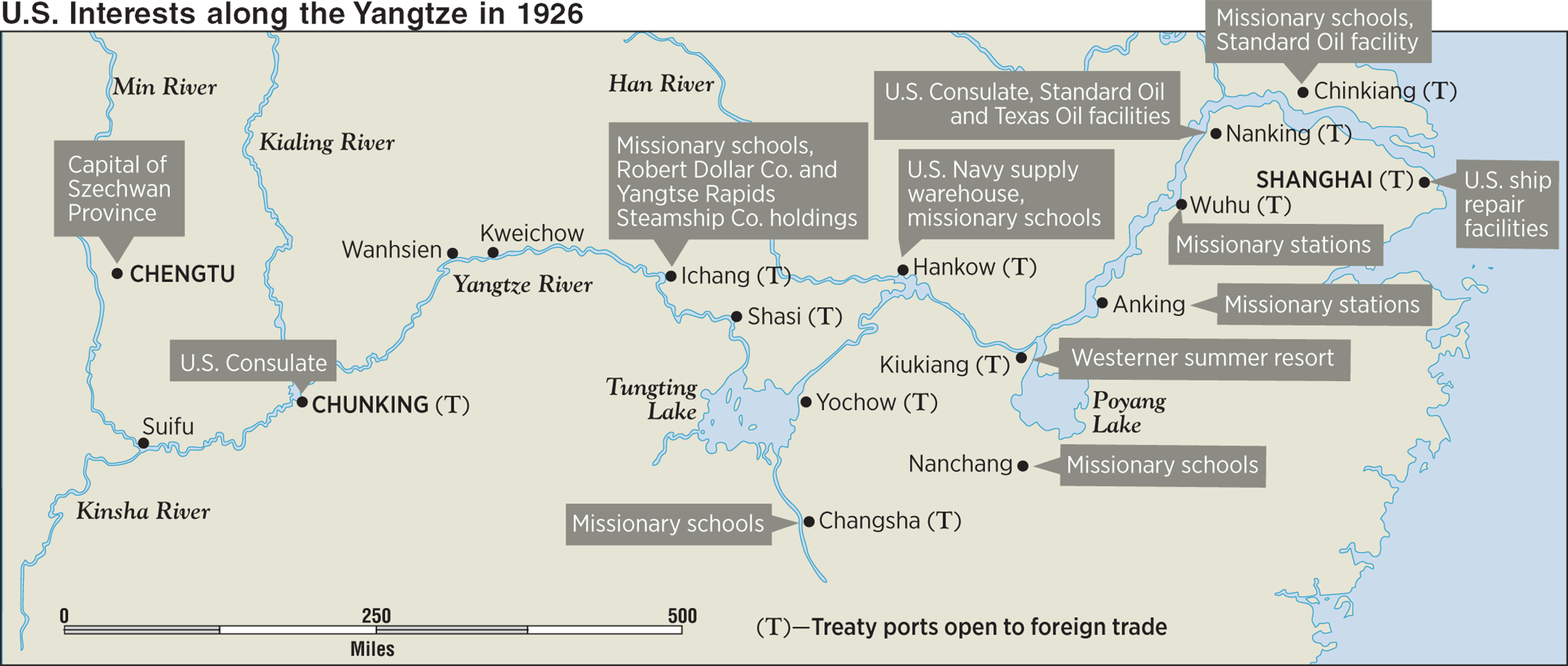

YangPat had orders to safeguard U.S. and Western interests while caught in the crossfire between warring factions. Standard Oil was a frequent beneficiary of U.S. naval action, as were missionaries striving to win new converts for Christ’s flock. This was an ambitious strategy to pursue while brandishing a small stick, but YangPat executed it with aplomb, considering the resources assigned. These verged on laughable.

Art imitates life. McKenna portrays the fictional gunboat San Pablo as a creaky old hulk whose steam propulsion plant has to be nursed from port to port through the ingenuity of her engineers, such as protagonist Machinist’s Mate First Class Jake Holman. Author Kemp Tolley aims similar mockery at the units assigned to the Yangtze Patrol in real life. In his history of the patrol, for example, he depicts the tugboat USS Palos, assigned to river duty in 1871, as typical of the inventory:

[The Palos] soon drew the scornful disapprobation of the CinC, Rear Admiral T. A. Jenkins: “She burns a great quantity of coal, is slow, and draws too much water to go to many places which a gun-boat of her tonnage should be able to reach; neither her appearance nor her battery is calculated to produce respect for her.”9

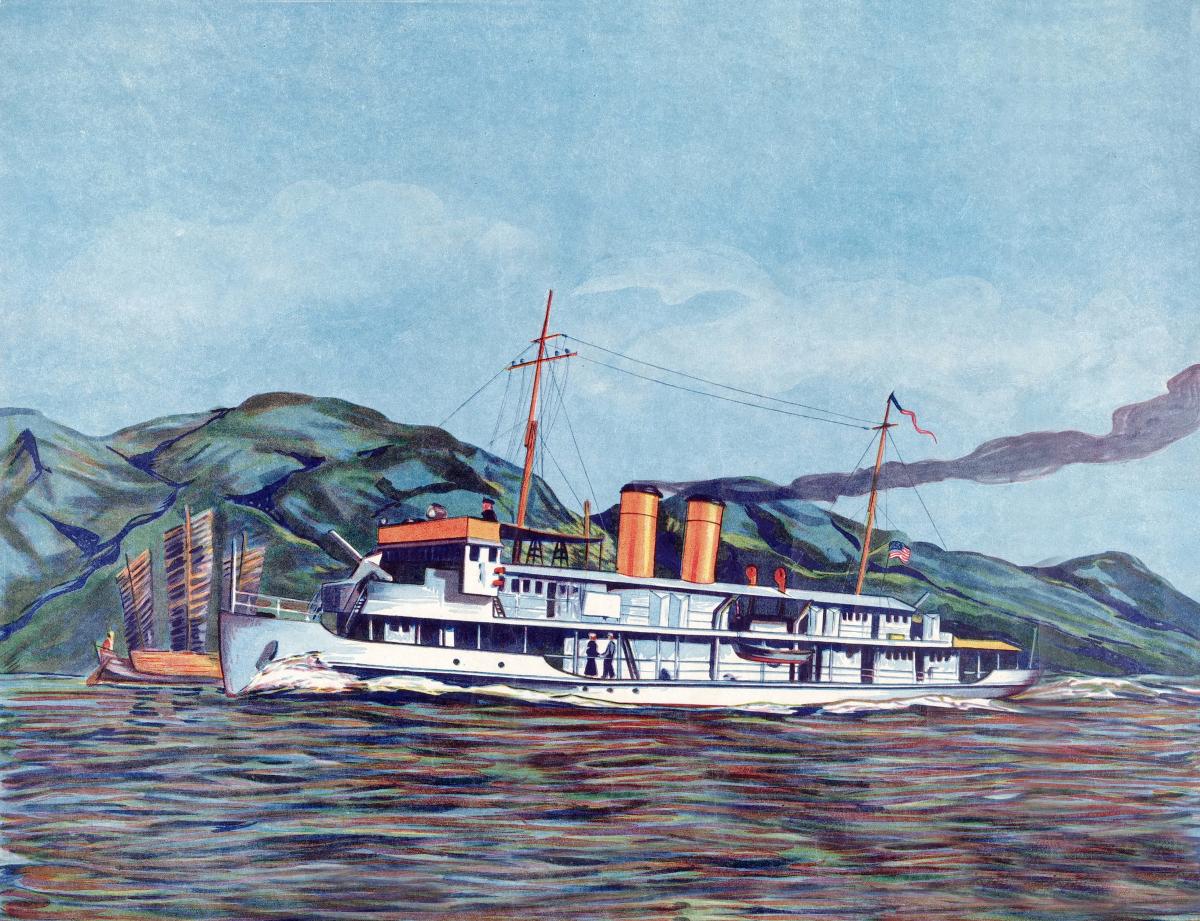

Elderly Civil War–era monitors found a place in the Yangtze Patrol inventory in its early days, as did gunboats wrested or purchased from Spain following the 1898 Spanish-American War. “At the dawn of the twentieth century,” reports Tolley, “the Asiatic Fleet resembled nothing so much as a fat mother hen and a great flock of tiny chicks,” namely, the armored cruiser Brooklyn along with a coterie of 24 gunboats, all but six obtained from Spain.10 He goes on to dub a ship class later proposed for riverine duty—Eagle gunboats of World War I vintage—“coffin-shaped atrocities.”11

As fighting ships—and implements of U.S. foreign policy and strategy—the patrol’s vessels left much to be desired.

Constable of the Great River

Yet the Yangtze Patrol accomplished much despite its ramshackle material state. The Navy Department instituted it to keep a variety of troublemakers at bay. The gunboats did so until the 1930s, when a rival great power, Japan, dispatched overwhelming military might to China. The gunboat flotilla was never meant to outface a hostile Imperial Japanese Navy or Army, and it could not. YangPat usually could outmatch lesser foes it faced. While it could never equal the combined might of even a Qing Dynasty in decline, or of armies commanded by local generals, it could deploy manpower or firepower superior to the segments of the opposing forces it was likely to encounter at specific scenes at specific times.

Gunboat crews, then, could make themselves locally superior while remaining inferior on the whole—and superiority at the decisive place and time is the keystone to tactical, operational, and strategic efficacy. The antagonist often was an isolated band of Chinese soldiers beset by slipshod marksmanship and equipment. Tolley constantly disparages the standards common among Chinese troops. Whenever that was the case, a disciplined and proficient though outnumbered gunboat crew could prevail by wringing maximum combat power out of sparse resources. Well-aimed shots from, say, a gunboat’s 6-pounders could yield greater tactical impact than sporadic Chinese artillery or small-arms fire.

As one U.S. consul in Shanghai put it, the gunboats’ goal should be to impress on prospective adversaries the “certainty of retribution” that would follow any offense.12 Adversaries might desist from infringing on U.S. treaty rights in the first place, if they knew they could not overpower Yangtze Patrol warships on the scene, or that the U.S. flotilla would mete out swift and sure reprisals should they transgress. The river force would deter.

There is a scattershot quality to YangPat’s operational history. Constabulary duty unfolds in vignettes—not the continuous narratives characteristic of wartime military campaigns, when one tactical action leads to the next and the next until one combatant triumphs and the other yields. Richard McKenna imposed a coherent storyline on his fictional account of Yangtze life, that of Jake Holman and his Chinese friend Po-han; otherwise, The Sand Pebbles never would have succeeded as a novel. Kemp Tolley’s history, by contrast, reads like a collection of sea stories. An old salt’s love for spinning yarns doubtless in part shaped his account, but its episodic character also stems from the whack-a-mole nature of constabulary work.

Constabulary duty is a “cumulative” endeavor, as another veteran of the Asiatic Station, Rear Admiral J. C. Wylie, labels it in his treatise Military Strategy. Military folk, he maintains, prefer the “sequential” approach to strategy because actions come after each other in time and space. It allows operational overseers to plot progress on a map or nautical chart using vectors or continuous curves that aim toward the final goal. It promises a clean victory. But Wylie adds that

there is another way to prosecute a war. There is a type of warfare in which the entire pattern is made up of a collection of lesser actions, but these lesser or individual actions are not sequentially interdependent. Each individual one is no more than a single statistic, an isolated plus or minus, in arriving at the final result.13

Submarine warfare is a quintessential cumulative campaign. Sinking a single freighter or transport makes little difference to the larger effort. Sinking lots of freighters and tankers in individual encounters over time can make an enormous difference. Yet Wylie’s insight applies as well to peacetime pursuits as to warfare.

In fact, constabulary endeavors entrusted to armed forces in times of uneasy peace resemble police work or efforts to bolster public safety and health more than they do wartime campaigning against foes who can be defeated. Yangtze gunboats responded to pleas for help from business firms or religious establishments much as police cruisers, engine companies, or ambulances respond to emergency calls in civilian life. Emergency services never face enemies sent by foreign governments. Police forces battle lawbreakers—private malefactors, in other words—while first responders combat nonhuman menaces such as fire, natural disasters, and disease.

Whether trying to manage Yangtze River chaos a century ago or American civil society today, responders attempt to improve the environment cumulatively by correcting or blunting the impact of many minor problems unrelated to one another in time or space. YangPat sought to improve the political and strategic environment for U.S. and Western interests, responding when small-scale troubles erupted along the Great River.

And YangPat succeeded for a time, until civil and foreign war consumed China. Creeping anarchy and great-power encroachment eventually rendered gunboats an unfit implement for the surroundings. A weak-seeming force, then, can fulfill important goals—but only while the circumstances remain congenial to its mode of operations.

Diplomats in Navy Blue

But how can the U.S. Navy extract real value from meager resources? Judging from the Yangtze Patrol’s record, Navy magnates should nurture certain habits in skippers they expect to send into unsettled surroundings on constabulary errands.

Independence of Mind and Deed. Like the sailors heralded in the 1921 Annual Report, mariners must realize they are diplomats, emissaries who send messages about U.S. power and resolve. What they do—or do not do—could matter a great deal to U.S. foreign policy.

Cultural Acquaintanceship. Knowing national customs and folkways will help naval diplomats tailor their words and actions to the audience while avoiding giving offense. Clashes typically flared in the Yangtze Valley when foreigners—whether through arrogance or ignorance—did something to affront Chinese mores. Tradition-minded Chinese protested, sometimes violently, and the Yangtze Patrol had to come to the rescue of foreign interests or people. Learning about the setting where naval forces will perform constabulary work is paramount to avoid wasting resources or enraging the local populace against the United States. Temperance and forbearance are virtues when doubt exists about the blowback some action may elicit.

Enterprise. Kemp Tolley relates a fascinating tale that has modern resonance. In 1921, banditry on the upper Yangtze had brought steamer traffic to a virtual standstill, and Asiatic Fleet officialdom was unsure how to restart it. Standard Oil representatives appealed to the captain of the gunboat Monocacy (PG-20) for help and proposed an unconventional solution: convoys of junks reflagged under the Stars and Stripes, loaded with oil, and escorted by a “posse of Monocacy sailors riding a houseboat.” That May, the experiment got under way with apparent success—until a force of armed men ambushed one of the houseboats, grievously wounding a bluejacket. Asiatic Fleet Commander-in-Chief Admiral Joseph Strauss summarily terminated the reflagging experiment.14

The experiment nonetheless was worthwhile. Many if not most madcap ideas will fall short when subjected to field trials. Even so, it is hard to sort the good ideas from the bad without first putting them to the test. Today’s U.S. Navy leaders should reward industry and ingenuity, just as they should permit local commanders the independence to get to know the theaters where they are assigned to operate and to orchestrate matters the way they see fit. Nourish a bustling culture in the ranks, and the contemporary Navy may live up to the standard set by River Rats a century ago.

1. Kemp Tolley, Yangtze Patrol: The U.S. Navy in China (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1971), 13–16.

2. John B. Hattendorf, “Introduction,” in J. C. Wylie, Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control (1967; reprint, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), xi–xiii.

3. For convenience’s sake I use Yangtze Patrol and YangPat to denote the gunboat force both before and after it received the name in 1919.

4. U.S. Secretary of the Navy, Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year (Including Operations to November 15, 1921) 1921 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921), 6–7.

5. Hal Brands, “Paradoxes of the Gray Zone,” Foreign Policy Research Institute E-Note, 5 February 2016.

6. Tolley, Yangtze Patrol, 5.

7. Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (1890; repr., New York: Dover, 1987), 43–44.

8. Richard McKenna, The Sand Pebbles (New York: Harper & Row, 1962).

9. Tolley, Yangtze Patrol, 34.

10. Tolley, 54.

11. Tolley, 98.

12. Tolley, 97.

13. Wylie, Military Strategy, 22–26.

14. Tolley, Yangtze Patrol, 98.