The log of the British 74-gun ship-of-the-line Monarch recorded the death of Admiral John Byng in the starkest of terms: “At 12 Mr Byng was shot dead by 6 Marines, and put into his coffin.” We can sense the care with which the words were chosen to describe in neutral terms a significant political event at a time when politics was the lifeblood of the British Navy.

Why was Byng executed? It was not pure politics, and it was not just the malice of a king, frustrated by the performance of his navy and army in the first year of the Seven Years’ War. John Byng, the son of a famous admiral, with a lifetime of honorable sea service behind him, found himself at the center of a perfect storm of circumstances that inexorably led to his death.

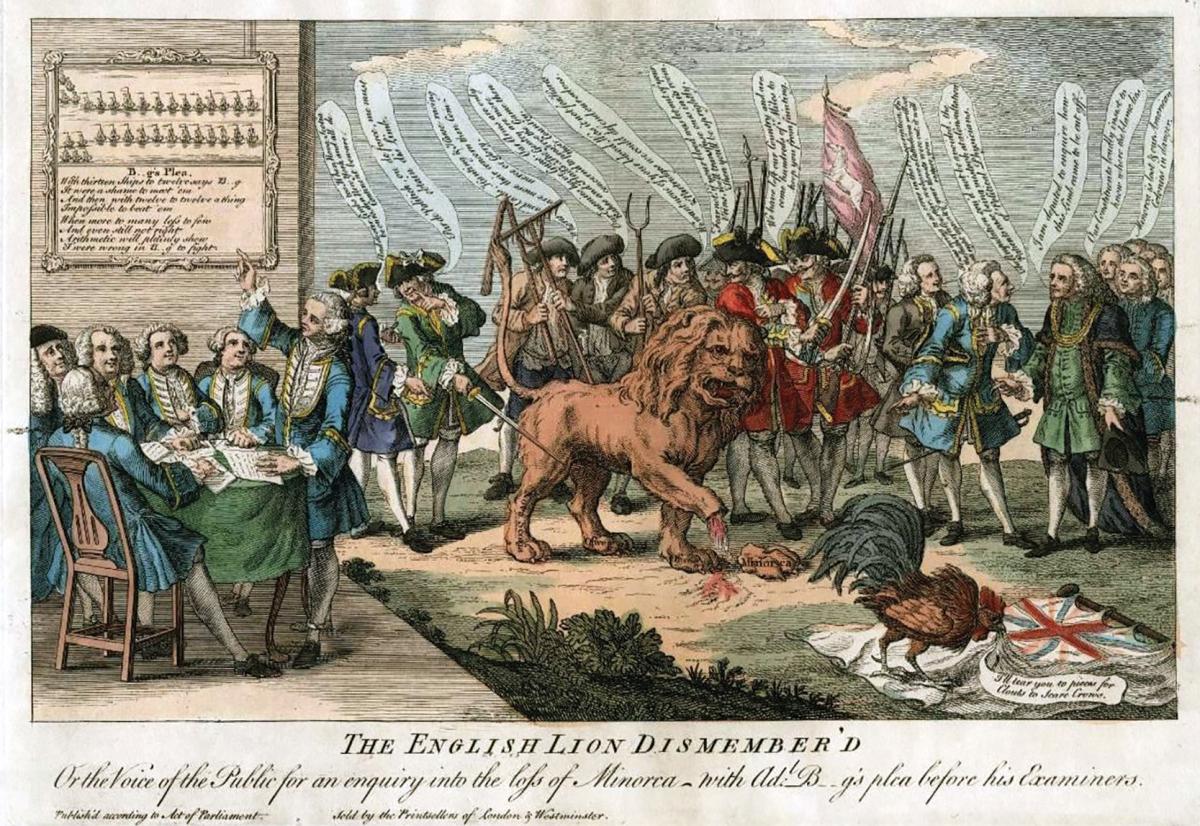

Failure at Minorca

The facts mostly are uncontested. In late 1755, before war had been declared, the British government learned that an invasion force was gathering in the south of France. Its objective was not initially clear; it could have been Britain, North America, or Gibraltar. However, most thought it must be the island of Minorca, home to the British Mediterranean Squadron, lying just 200 nautical miles off the French naval base at Toulon.

Minorca was an attractive target for the French. First, without it the British Navy would find the task of blockading or even watching Toulon much more difficult. Second, it could be offered to Spain, its previous owner, as an inducement to join France in the forthcoming war. Third, if the Spanish did not take it, Minorca could be traded for the return of French Caribbean sugar islands or for territory in North America in peace negotiations with Britain at the conclusion of the war. Finally, it offered the chance of a quick victory, because the peacetime British Mediterranean Squadron consisted of only a handful of the smallest types of ships-of-the-line and a few frigates.

By early 1756, the British government had determined that the objective of the Toulon force indeed was Minorca. Byng was ordered to prepare a squadron to relieve the island but suffered from the slow pace at which ships were made available and by that perpetual 18th-century naval problem—a lack of trained seamen. He eventually left Portsmouth on 6 April with 1,700 nautical miles to sail to his destination. Four days later, Admiral Roland-Michel de la Galissonière’s ships sailed from Toulon with an invasion army embarked. They only had to cover 200 nautical miles.

The French army landed at the undefended western end of the island on Easter Sunday, 18 April 1756. The heavily outnumbered British garrison retired behind the walls of Fort St. Philip, outside Mahon at the island’s eastern end, and by 22 April the fort was under siege.

Byng arrived at Gibraltar on 2 May, stayed six days, and left without having taken on board the reinforcements for Fort St. Philip that the governor of Gibraltar had been directed to provide. He arrived off Mahon on 19 May.

A tactically inconclusive three-hour naval battle was fought on 20 May, after which the French withdrew, leaving a badly battered British squadron. Four days later, Byng called a council of war on board his flagship, the 90-gun Ramillies, at which it was decided to return to Gibraltar to refit without attempting to contact Fort St. Philip. Byng’s squadron arrived on 19 June, only two weeks ahead of the Antelope, from Portsmouth, bearing Admiral Edward Hawke with orders to relieve Byng and send him home for a court-martial. On 29 June, Fort St. Philip surrendered.

Byng’s court-martial convened on 27 December at Portsmouth. He was found guilty under the 12th Article of War in that he did “not do his utmost,” and on 27 January, he was sentenced to death. The sentence was carried out on 14 March 1757.

Why Was Byng Executed?

On one level, the answer is simple. Byng was ordered to prevent the French from capturing Minorca, but he withdrew without completing the job. The charge on which he was found guilty allowed no discretion in sentencing; the penalty was death.

And yet, there is more to this drama than meets the eye. Only a decade earlier it would have been inconceivable that a man such as Byng would have been treated so harshly. He was at the heart of the political and naval establishment, and the Admiralty and government were full of his friends. So, what went wrong for John Byng? There is no single answer, and we must look widely into the navy, the government, the monarchy, and society for the answers. Consider the following factors:

The professionalization of the Royal Navy. In the first half of the 18th century, the British Navy could not be relied on to produce the effect that the king and the government demanded. It displayed moments of brilliance, but they were the exceptions; there were too many examples of naval commanders willfully amending their orders and even declining to engage the enemy. The notorious case of the 1744 Battle of Toulon exemplified the problem; a subordinate admiral simply refused to obey the signals of his superior, with disastrous results.

In the late 1740s, there was a coherent movement to professionalize the navy. Much of the thinking was enshrined in the 1749 Navy Bill, which included significant amendments to the Articles of War. It was the new text of Article 12, addressing engagement of the enemy, that proved fatal for Byng.

The previous rather laissez-faire wording “(shall) suffer pain of death or other punishment as the circumstances of the offence shall deserve and the court martial shall judge fit” was replaced by the more absolute “every such Person so offending, and being convicted thereof by the sentence of a Court Martial, shall suffer Death.” No alternative punishment was offered. Byng’s was the first important case to be tried under the new Article 12.

Political influence. In the 1740s and 1750s, the ruling Whig party was split between the self-styled Patriots and the Authoritarians. The Authoritarians believed in a top-down approach to governance, and they forced through the professionalization of the navy and its subordination to government. The Patriots, meanwhile, believed that a small volunteer navy, supplemented by privateers in time of war, and an organized militia posed less of a threat to the liberties of the people than a large standing navy and army.

Byng’s actions represented everything about the old navy that frustrated the Authoritarian Whigs, and unfortunately for Byng, their faction was in the ascendant.

The naval and military failures of 1755 and 1756. By the time Byng came to trial, not only had Minorca been lost, but in America, General Edward Braddock’s expedition against Fort Duquesne had been beaten and Fort Oswego had fallen. In the Caribbean, a British ship-of-the-line, the Warwick, had been captured, and in the East Indies, Calcutta and Fort William had been lost. The French appeared to have gained the initiative; this was no time to excuse naval failures.

The Western Squadron. British naval strategy in the Seven Years’ War and later pivoted on the Western Squadron. It held the English Channel secure against invasion, blockaded the French and Spanish Atlantic ports, protected merchant convoys during the most dangerous part of their passage, and brought the enemy’s battle fleets to action. Unsurprisingly, the Western Squadron absorbed the cream of the fleet’s ships, its best leaders, and most of its trained manpower. The need to preserve the fighting power of the Western Squadron made First Lord of the Admiralty George Anson cautious in committing ten of his precious ships-of-the-line to the Mediterranean. As a result, Byng faced the French after their army landed and with a bare parity of force. Faster deployment and more ships could have resulted in a different outcome.

The slow passage. Byng’s orders expressed urgency, but his squadron took 43 days to sail to Minorca. There were any number of valid reasons for a slow passage in the days of sail, such as adverse winds, high seas, and damage to sails and hulls. However, to anyone who had not sailed with him, Byng’s progress appeared particularly tardy.

Operational and tactical problems. In Gibraltar, Byng absorbed two of the original Mediterranean Squadron ships into his line-of-battle, and battle was joined with 12 ships on each side. The admiral’s windward position should have given him an advantage, but when the Intrepid, the sixth in line, was damaged, a gap opened between the van and the rear. Most of the ships that followed the Intrepid, including Byng’s flagship Ramillies, barely engaged the enemy, while the first six ships of the British line suffered a serious mauling.

When the French withdrew, content that they had—for that day—prevented Byng from relieving Fort St. Philip, the British fleet was too severely damaged to follow. Byng could have stayed on station to carry out his orders; instead he decided to leave for Gibraltar to refit his ships, covering his decision with a council of war. The members of the court-martial board, while unanimous in recommending clemency, despaired at the admiral’s apparent apathy.

The isolation of the Mediterranean. In wartime, with the land route closed, four weeks was considered a reasonable time for dispatches from Minorca to arrive in London. However, de la Galissonière merely had to send a ship back to Toulon, and from there a well-organized overland system whisked his letters to Paris in perhaps three or four days. A copy of the French admiral’s report reached London via the Spanish ambassador on 3 June, only 14 days after the battle and long before Byng’s account reached the Admiralty. De la Galissonière’s version of events set in motion Byng’s recall and the convening of a court-martial. By the time Byng’s own account was read, it was too late. The damning narrative of tactical failure and abandonment of Fort St. Philip had been established.

The king’s antipathy. George II thought himself a warrior-king. He was the last British monarch to lead his army into battle—at Dettingen in 1743 during the War of the Austrian Succession—and was intolerant of what he saw as cowardice or lack of zeal in his naval and military commanders. George was furious when he read Byng’s pessimistic letter sent from Gibraltar before the battle. “This man will not fight,” the king declared. He was not inclined to extend his clemency to Byng.

The Admiral’s Legacy

No single circumstance sealed John Byng’s fate. He was a victim of the politicization of the navy, the isolation of the Mediterranean, the turmoil of mobilization for war, and his own lack of resolution. Then did his death leave a positive legacy for the service? The navy certainly was a more reliable tool of the government during the Seven Years’ War and the remainder of the 18th century. The records do not offer much, but the example of Byng’s sentence probably was a contributory factor in the astonishing increase in the Royal Navy’s fighting spirit. The French writer Voltaire offered an opinion when he referred to Byng’s execution in his satirical novel Candide: “In this country, it is wise to kill an admiral from time to time to encourage the others.”

Admiral John Byng died bravely, facing his executioners’ muskets across the few yards of the Monarch’s quarterdeck. He even managed a jest as he addressed his cousin before dropping his own handkerchief as a signal for the Marines to fire: “God bless you my friend, don’t stay here, they may shoot you too.”