During the fourth month of World War II, on placid waters off South America, one New Zealand and two British cruisers intercepted the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee. After they exchanged fire for 83 minutes, the British squadron disengaged. The German ship withdrew into the neutral port of Montevideo, Uruguay, and several days later was scuttled.

The Graf Spee’s self-destruction eliminated a powerful commerce raider, giving the Royal Navy a strategic victory. It also provided an opportunity to counter murmurs regarding Admiralty wartime mismanagement and questionable decisions by the First Lord, Winston Churchill.

Churchill had sent the aircraft carrier HMS Courageous to hunt U-boats, but a U-boat sank her. The armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi was sent to intercept German merchant ships, but battle cruisers sank her. The battleship Royal Oak was anchored in the fleet’s sanctuary inside Scapa Flow, but a U-boat sank her. The Royal Navy had no counterbalancing victories. A rousing sea battle in which it prevailed over fearsome odds was just the ticket to regain public support, solidify Churchill’s place as head of the Admiralty, and bolster fleet morale.

Shortly after the battle, the Admiralty created a report for public release that contrasted the small cruisers to the huge pocket battleship wielding “a considerable advantage in armament.”1 Despite daunting odds, the Royal Navy engaged with alacrity and “immediately developed a high rate of fire, combined with great accuracy.” Tormented by cruisers making “excellent practice” with “very accurate” gunnery, the Graf Spee found the “gunfire too hot” and fled. His Majesty’s Stationery Office published the pamphlet in 1940, and the public bought it, tuppence a copy.

Three generations of historians have accepted the pamphlet’s assertion that the British fought a brilliant action, overcoming intimidating odds. Time magazine marveled at the victory over “one of the most formidable ships afloat.” A respected historian judged that the British commander “handled his ships as well as anyone might have expected,” crediting him with “cool bravery with shrewd and rational analysis” emulating “Nelson’s genius.”2

Propaganda Claims

Were the British outmatched? The pamphlet offered two metrics: weight of broadside and ships’ tonnage. The Graf Spee’s broadside was given as 4,700 pounds, versus 3,136 pounds for the three cruisers, a 50 percent German advantage. This was one of Churchill’s favorite measures, used often when haranguing for bigger guns on battleships.

But broadside weight ignores rate of fire. The Graf Spee’s main (11-inch) and starboard or port secondary (5.9-inch) batteries could fire 13,121 pounds per minute, versus the cruisers’ one 8-inch and two 6-inch batteries’ 21,760 pounds—a 66 percent British advantage. A shell’s destructive power is not directly proportional to weight. The Royal Navy assessed that an 11-inch shell weighing six times a 6-inch shell was only three times as damaging.3 Combining rate of fire and shell effectiveness, the British had a firepower advantage of 125 percent.

Standard tonnage for the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter was 8,550, the Leander-class light cruisers HMS Ajax and HMNZS Achilles were around 7,000 tons each—a total of about 22,550 tons. With the Graf Spee at about 14,000 tons, the British had a 60 percent tonnage advantage.

In both tonnage and firepower, the propaganda “spin” was wobbly.

What Naval Officers Believed

Prior to World War II, the Royal Naval College and the U.S. Naval War College developed methodologies to model the combat performance of warships and gauge their comparative value. These models provide insight into how contemporary naval officers would compare the forces.

The War College’s Fire Effect System accounted for shell size and trajectory, armor protection and penetration, gun capabilities, spotting and fire control, and many other factors.4 Updates kept it “on as accurate a basis as is practical for use in tactical study.”5 The system assessed a 93 percent survivability advantage to the British. Measuring total combat power, at ranges from 4,000 to 21,000 yards, the British squadron’s relative fighting strength was 1.5 to 3.0 times more powerful than the Graf Spee’s.6 Square law of combat formulas estimate the Graf Spee would be destroyed with 11 to 44 percent damage to the British.7

The German ship was designed to be “stronger than anything faster, and faster than anything stronger.” The British recognized she was a serious threat to their trade routes. Captain Henry Harwood, on the staff of the Royal Naval College Senior Officer’s War Course from 1934 to 1936, was an acknowledged expert who lectured on tactics to fight pocket battleships.8 Commodore Harwood would command at the River Plate.

A tool available to him was the Royal Navy’s wargaming system. The Royal Navy’s history with wargaming dated back to 1888. Wargaming was added to the Royal Naval College course in 1907, with exercises twice a week. The latest incarnation of the rules, C.B.3011 (1929, with updates), was used extensively at the college and on board warships for training and testing tactics.9 Harwood would have used the rules to develop and demonstrate tactics against pocket battleships.

C.B.3011 assesses a 133 percent survivability advantage to the British squadron. In addition, a shell able to penetrate armor triggered a 1 in 30 chance to inflict a magazine explosion. The Graf Spee’s 11-inch guns could penetrate British cruiser armor at all ranges, as could the Exeter’s 8-inchers against the Graf Spee. With a rate of fire twice the Graf Spee’s, odds favored the Exeter scoring the first magazine hit at decisive ranges.

The rules awarded a 25 percent accuracy bonus at ranges of more than 15,000 yards for concentration fire, a British long-range gunnery technique. A controlling ship in a formation would transmit her fire-control solution. Other ships would correct for their positions relative to the controller. All would shoot simultaneously so their shots would fall in a single tight group. This was intended to reduce spotting confusion when multiple ships fired on the same target.

Another British technique was flank marking. At long range, a firing ship could tell only if her salvo was long, short, or straddle by whether the base of the shell splash was obscured by the target’s hull. Distances over or short could not be determined. With flank marking, a ship observing from a different angle would estimate and transmit the distance over or short, allowing the firing ship to adjust precisely.

C.B.3011 assessed Harwood’s squadron’s relative fighting strength at 3.7 to 5.9 times greater than the Graf Spee’s. The square law suggests the pocket battleship would be destroyed with less than 10 percent damage to the British.

Battle Tactics

These considerations suggest the Exeter should close to where her greater rate of fire would give her a better chance of obtaining the first magazine hit. The light cruisers should engage from outside 15,000 yards, taking advantage of concentration fire. The squadron should split and implement flank marking. These are the tactics Harwood would employ.

Reenacting the battle using C.B.3011, the Graf Spee was destroyed in 19 minutes. The Exeter took 72 percent damage, the Ajax 2 percent, with the Achilles undamaged, for 31 percent total damage to the British squadron.

Thus, contemporary methodologies from two navies both calculate that Harwood’s squadron was on the order of two to five times more powerful than the pocket battleship and was capable of destroying her without losing a ship. As a Naval College staff member lecturing on tactics to counter pocket battleships, Harwood must have played this engagement many times. With C.B.3011 as his guide, he would expect his squadron to sink the Graf Spee handily.

In December 1939, the Admiralty had eight squadrons hunting pocket battleships. They were days apart. It makes sense that the Admiralty would constitute every group, including Harwood’s, with sufficient power to destroy their prey. Underdogs they were not.

The Commodore’s Intentions

Harwood’s prebattle instructions directed his captains to “Attack at once by day or night” and act “without further orders so as to maintain decisive gun range.”10 That key word—decisive—has escaped historical attention.

After the battle, Harwood tried to brush off the idea he intended a decisive engagement. In the tradition of Horatio Nelson’s letters to Lady Emma Hamilton, Harwood wrote his wife: “A raider is thousands of miles from his base. Attack him, make him use his ammunition. Hit him and he can’t repair his damage without going in and risking internment. . . . Some other unit can come later and dispose of him. It is not necessary to sink a raider, lovely of course to do so, lame him is most valuable.” This extract is quoted in most historical accounts.

Accepting the propaganda that the British were the inferior force, most histories take from this letter that Harwood’s goal was to damage the Graf Spee and empty her magazines. They applaud when this is achieved. However, the British had the superior force, and C.B.3011 gave Harwood every expectation his tactics would lead to a decisive result. He intended and expected to destroy the Graf Spee.

Harwood’s letter to his wife is disingenuous, an after-the-fact attempt to imply his objective was only to “lame him.” He was covering for a botched battle. The British commodore knew his force outmatched the Graf Spee. This realization drives a different interpretation of the battle, the course of which cognitive science can frame (and perhaps explain).

Battle Analysis

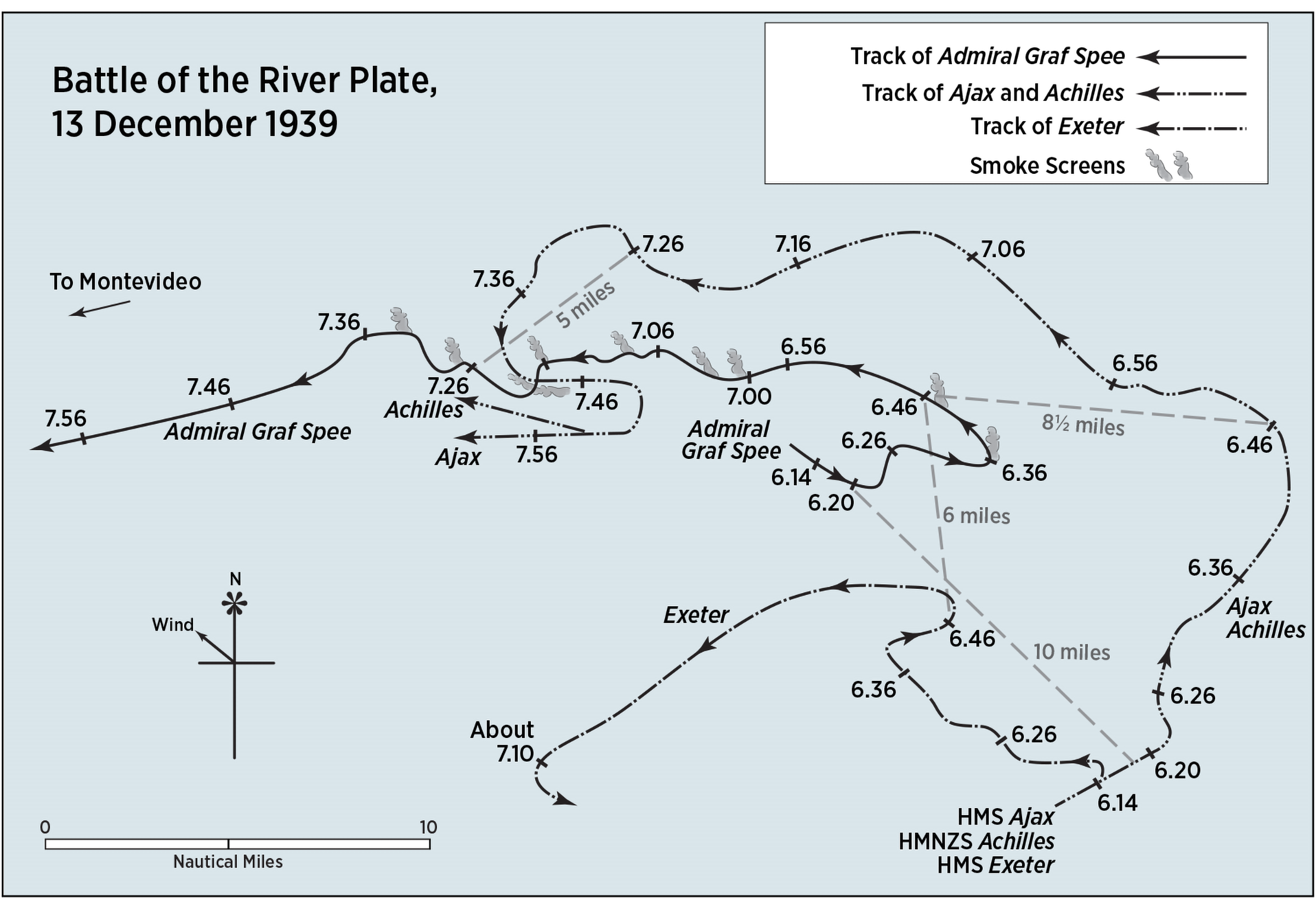

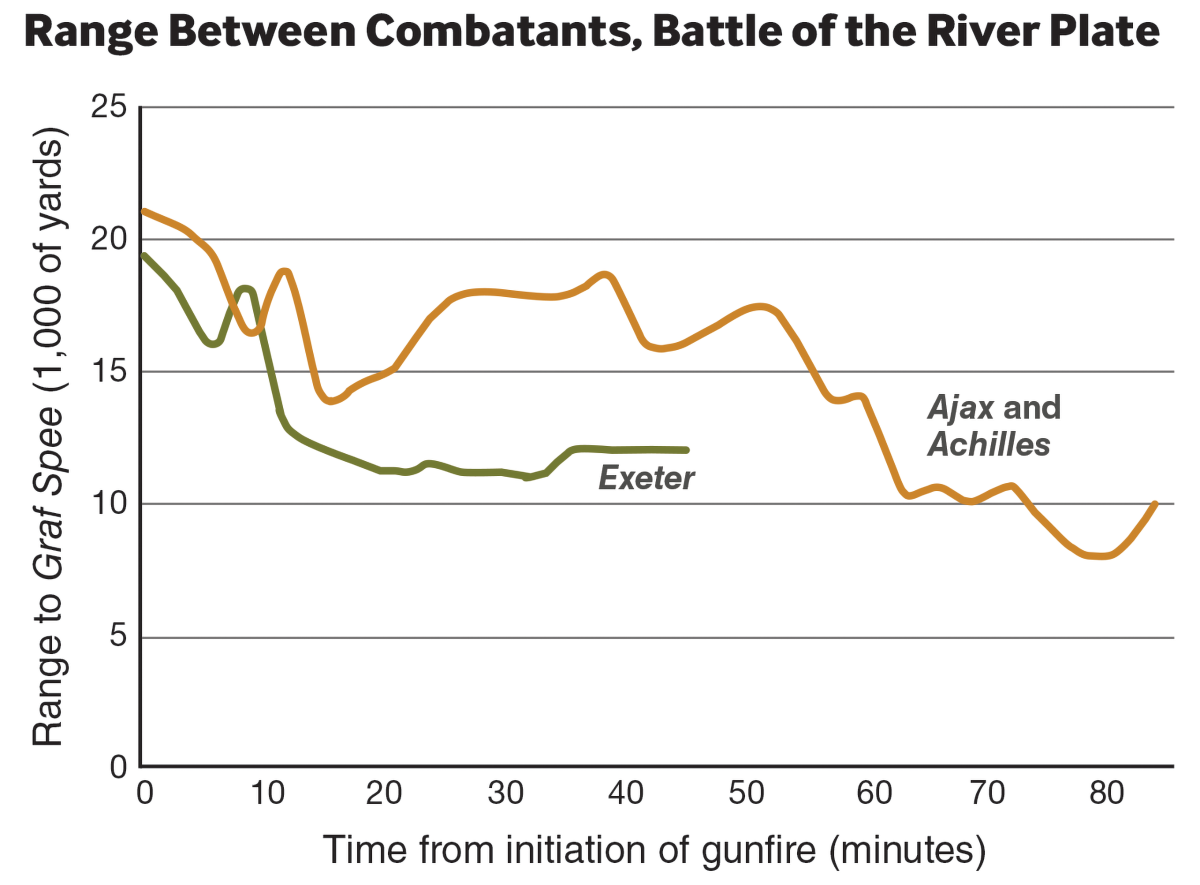

With a nine-knot speed advantage, the British controlled the range and terms of the engagement. Harwood, on board the Ajax with the Achilles in formation astern, initially maneuvered to the northeast and stayed outside 15,000 yards to employ concentration fire.11 The Exeter detached and turned toward the Graf Spee to close to inside 11,000 yards, decisive range, with a shell time-of-flight of less than 13 seconds, per Harwood’s prebattle instructions. The Exeter was heading into a one-on-one duel in which she was outmatched. The only reason Harwood would commit his heavy cruiser to this risk was if he was striving for an immediate decisive result—to sink the Graf Spee.

The German ship quickly hit the Exeter. Her radio was destroyed, ending any hopes of flank marking.12 After 35 minutes, both her forward turrets were demolished, her fire-control system disabled, and she had serious flooding forward. The heavy cruiser bravely maintained decisive gun range as ordered, with only a single remaining 8-inch gun barking away inaccurately.

With Harwood steaming away to the northeast, the Graf Spee could have smashed the crippled Exeter. Without flank marking, the commodore had no reason to keep his force separated. Yet he did not close to support the imperiled cruiser. Harwood ignored the 1939 Fighting Instructions, which state, “Mutual support must be given and expected between all classes of ships.”13

Harwood likely was suffering from status-quo bias, the tendency to adhere to a plan beyond the point where it remains the best course of action. He expected the Graf Spee to be destroyed quickly, so a course reversal to close and directly support the Exeter would disrupt his existing firing solutions. Confirmation bias (the tendency to see what you expect to see) had him believing his guns were hitting. In ignoring the Exeter, he probably was in the grips of target fixation, the tendency to direct attention exclusively on a target without processing or seeking other incoming or relevant information.

At times firing more than five salvoes a minute, the light cruisers scored only four hits in the battle’s first 18 minutes, expending more than 1,000 rounds. That 0.4 percent hit rate belies the propaganda claim of “great accuracy.”14

Then a series of misadventures disrupted British fire control. Concentration fire was lost when the Achilles took splinters through her main director, killing critical personnel. It was reestablished but again lost when the radio link failed. The Ajax’s gunnery officer became confused when the Achilles dropped out of concentration fire without his knowledge, leading to 25 minutes of misdirected salvoes. The Ajax launched a spotter aircraft, but because of staff inattention, communications were not established for 12 minutes. When aerial spotting was finally implemented, the aircrew misidentified salvoes and signaled the wrong corrections. The Ajax fired “over” for 14 minutes.

The Graf Spee was making smoke, which the wind kept between her and the light cruisers. Harwood did not act to clear his line of fire; therefore, his gunners had to spot and take ranges with intermittent visibility. The commodore kept his light cruisers outside 15,000 yards even while concentration fire was not working. For 42 minutes (T+18 to T+60) the light cruisers probably did not score a single hit.

After 50 minutes, the Graf Spee’s speed had not diminished and all six of her main battery guns were firing. Likely affected by confirmation bias and status-quo bias and in denial that his plan was not working, Harwood persisted in pumping out rounds at long range for nearly an hour without discernible effect. He did not grasp that the long-range accuracy predicted by C.B.3011 was not being realized.

Harwood eventually came to that epiphany. He decided to close to decisive range. His first moves were meek: Twice he turned away to allow his after guns to bear, slowing his rate of closure. He still was not hitting consistently.

He finally decided to close aggressively. At T+56, Harwood signaled, “Proceed at utmost speed.” This signal relieved the Achilles of the requirement to maintain formation. Harwood was accepting a higher risk of magazine or engineering hits that might slow his light cruisers and allow the Graf Spee to escape. This makes sense only if he intended an immediate decisive result.

The range dropped to under 10,000 yards, the cruisers finally cleared the smokescreens, and their guns began to hit consistently. The pocket battleship shuddered under hits and was flailed by splinters from near misses. Her captain was wounded twice, then knocked unconscious by an explosion. Her main rangefinder wiring was cut; accuracy suffered from confused reporting from alternate rangefinders.

A decisive victory was within Harwood’s grasp. Then, abruptly, he was informed his flagship’s main battery had 20 percent ammunition remaining, which likely intruded into his target fixation. The range was 8,000 yards and closing; the Graf Spee was not hitting the light cruisers, and she was being savaged by nearly every British salvo. At close range, 20 percent was plenty to finish the pocket battleship. But Harwood—shocked by the sudden revelation of the ammunition state, beset by cognitive dissonance from the failure of his original expectations for the battle, and likely disconcerted by the unknown consequences of running out of ammunition—retreated.

With 440 rounds remaining, Naval War College accuracy tables at 6,000 yards give 97 hits. C.B.3011 predicts 48 hits, twice what the rules required to destroy the Graf Spee. Harwood should have known he was on the brink of decisive victory. To pile bungle onto blunder, the ammunition report was another staff mistake. The 20 percent applied only to one turret. The Ajax overall had 50 percent 6-inch ammunition remaining, the Achilles 30 percent.15

After the battle, Harwood justified his retreat by claiming the Graf Spee’s fire was too accurate. When the withdrawal order was given, the light cruisers had suffered only a single direct hit inflicted 13 minutes—a lifetime in battle—before the order to withdraw. German accuracy did not justify disengaging.

The Battle of the River Plate was not the Royal Navy’s brightest moment. Investigations, recriminations, and court-martials were forestalled when the Graf Spee was scuttled. Politics prompted Churchill to proclaim victory; congratulations and medals and promotions were dispensed; and British propaganda declared a triumph. Harwood was off the hook, and Churchill survived as First Lord and went on to become Prime Minister.

What Went Wrong?

The wargaming system used by the Royal Navy awarded an unrealistic percentage of hits at long range. That, and the promises of concentration fire and flank marking, encouraged Harwood to plan to fight his light cruisers at long range. With tongue firmly in cheek, one can suggest this was the first naval battle lost by a naval wargame.

The British shot poorly. Splinter damage to a fire-control director, sights obscured by smoke, and errors by the spotter aircraft contributed to the meager performance. Concentration fire was a flawed concept. With 16 shells landing in a close group, “short” shell splashes obscured “over” splashes. When the target was straddled, the spotter erroneously could call for an inappropriate “up” correction. The Ajax’s fire often was noted to be long. Concentration fire and flank marking were more hindrance than help and were not employed in later engagements with the German battleship Bismarck.

Most significant was Harwood’s performance. He did not support the Exeter, and only German forbearance allowed her to survive. Lured by the siren song of concentration fire and flank marking and misled by confirmation bias, the commodore was late to comprehend that his long-range gunnery was ineffective. He lost track of his ammunition expenditures and closed to point-blank range without first confirming he had sufficient ammunition to complete the engagement. Gripped by target fixation and a monumental loss of situation awareness, with poor support from his staff, he turned away from decisive victory.

1. The Battle of the River Plate: An Account of Events Before, During and After the Action up to the Self-Destruction of the Admiral Graf Spee (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1940), ADM 267/145, The National Archives, Kew, UK (hereafter NA).

2. Eric J. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 165–66. Similar assessments are in Dudley Pope, The Battle of the River Plate (London: William Kimber and Co., 1956).

3. C.B.3011, War Game Rules, 1929, ADM 186/78, NA.

4. The Comparison of Fighting Strengths with Questions and Solutions, July 1931, RG 4, Box 62, file 10, Naval Historical Collection Archives, U.S. Naval War College, Newport, RI (hereafter NWC).

5. Bureau of Ordnance, Office of Naval Intelligence, Division of Fleet Training, and others provide updates. Theory and Purpose of Fighting Strength Calculations, July 1936, RG 4, Box 70, File 1918, NWC.

6. Discussion of Numerical factors in Fire Effect Tables 1931, RG 35, Box 3a, File 23, NWC; Construction Fire Effect Tables 1922, with revisions to March 1930, RG 35, Box 9, File 6, NWC.

7. LCDR J. V. Chase, USN, Sea Fights: A Mathematical Investigation of the Effect of Superiority of Force in 1902 (1902), RG 8, Box 109, NWC. CDR Roy C. Smith, USN, The Fighting Value of Forces in Terms of Standard Battleships and in Relation to Ammunition Supply (1908), NWC. CDR W. L. Rodgers, USN, A Mathematical Examination of Combatant Endurance of Two Hostile Forces (1908), RG 8 Box 109, Folder 7, NWC. Frederick W. Lanchester, Aircraft in Warfare: The Dawn of the Fourth Arm (London: Constable, 1916).

8. Grove, The Price of Disobedience, 55.

9. Christopher Yi-Han Choy, “British War-Gaming, 1870–1914,” unpublished master’s thesis, King’s College, London, 30 August 2013, 33, 36.

10. Grove, The Price of Disobedience, 57.

11. For battle analysis, primary sources consulted are Graf Spee 1939, The German Story, ADM 223/68; Visit to the Wreck of Graf Spee, 1940, ADM 281/86; Graf Spee Shell Damage, ADM 281/85; Graf Spee Photographs and Technical Report, ADM 281/84; German Pocket Battleship Admiral Graf Spee Battle with H. M. Cruisers Achilles, Ajax and Exeter, ADM 1/19292; Report on Admiral Graf Spee: Action off the River Plate, ADM 1/9759, all NA.

12. Flank marking was not reported as initiated.

13. Fighting Instructions 1939, ADM 239/261, NA.

14. William Jurens assesses four 6-inch hits between 0631 and 0635 (T+14 to T+18) and no definite hits likely between 0635 and 0717 (T+18 to T+60). Hits unidentified by approach or descent angle may have occurred. Letter to the author, 10 April 2017.

15. Grove, The Price of Disobedience, 106.