Delving into the Legendary Nimitz Graybook

It’s been called the Holy Grail of Pacific war research—seven large volumes of “Command Summary” documents, which originally were bound in gray-colored binders. They present a record of what Admiral Chester Nimitz, Pacific Fleet Commander-in-Chief, knew and the information he based his decisions on during World War II.

At the 22 September symposium “The Nimitz Graybook: Chronicles of the Pacific War,” more than 250 attendees were treated to accounts of wartime operations as seen through the lens of the Graybook. Historians Craig Symonds, John Lundstrom, Timothy Orr, Richard Frank, Walter Borneman, and James Hornfischer wove in documents from the volumes to support their accounts and analyses of the Pacific conflict.

Also at the Fredericksburg, Texas, event hosted by the Nimitz Foundation and the Museum of the Pacific War, retired Navy Rear Admiral Samuel Cox, director of the Naval History and Heritage Command, discussed the fragile original Graybook volumes, which are under the Command’s care at the Washington Navy Yard. As a special treat, attendees received their own flash-drive copies of the Graybook.

A Family Funeral, a Navy Legacy

When Senator John McCain was laid to rest at the U.S. Naval Academy on 2 September, the moment felt to many like the passing of an era. But in remembering the life and career of the celebrated Navy pilot/Vietnam POW/political titan, it is perhaps best to see him as part of a continuum. For the McCain family name carries with it a legacy of military service—a legacy now being carried on by a new generation.

To say John McCain grew up in a Navy household would be an understatement. His father, John Sidney “Jack” McCain Jr., and grandfather, John Sidney “Slew” McCain Sr., made history as the first father-son combo to each make four-star admiral.

Father Jack, a World War II submarine commander, went on to become Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command, from 1968 to 1972—the year before his son finally was freed from prisoner-of-war hell.

Grandfather “Slew,” the first of the family to steer from Army service toward a naval career, would gain renown as a pioneer of carrier combat in World War II.

Prior to Slew and the Navy, the McCains had peppered the Army ranks: “Wild Bill” McCain pursued Pancho Villa in 1916. Major General Henry Pinckney McCain, a West Point graduate, is remembered as “the father of the draft,” having set up Selective Service in World War I. The McCains had fought in the Revolution, the Civil War (on the Southern side), and whenever contingincies arose down through generations. As Stars and Stripes noted, “By the Vietnam War, a McCain or one of their ancestors had fought in every American war.”

And now, even with the passing of John McCain, the family tradition continues: His son, John “Jack” McCain IV, a 2009 Naval Academy graduate, is currently a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy. And so the torch is passed to a new generation in a family with a remarkable record of service.

The Guns of ’18: Navy Commemorates WWI Centennial

Starting with the anniversary of the United States’ entry into World War I on 6 April 2017, through the anniversary of Armistice Day on 11 November 2018, the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) has commemorated the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Navy’s experiences during the war.

Commemoration efforts spanned the NHHC enterprise to include expanding its digitized collection of World War I–related history. On its website, the command provided access to hundreds of photographs, publications, and resources covering various aspects of the Navy’s experiences during the war.

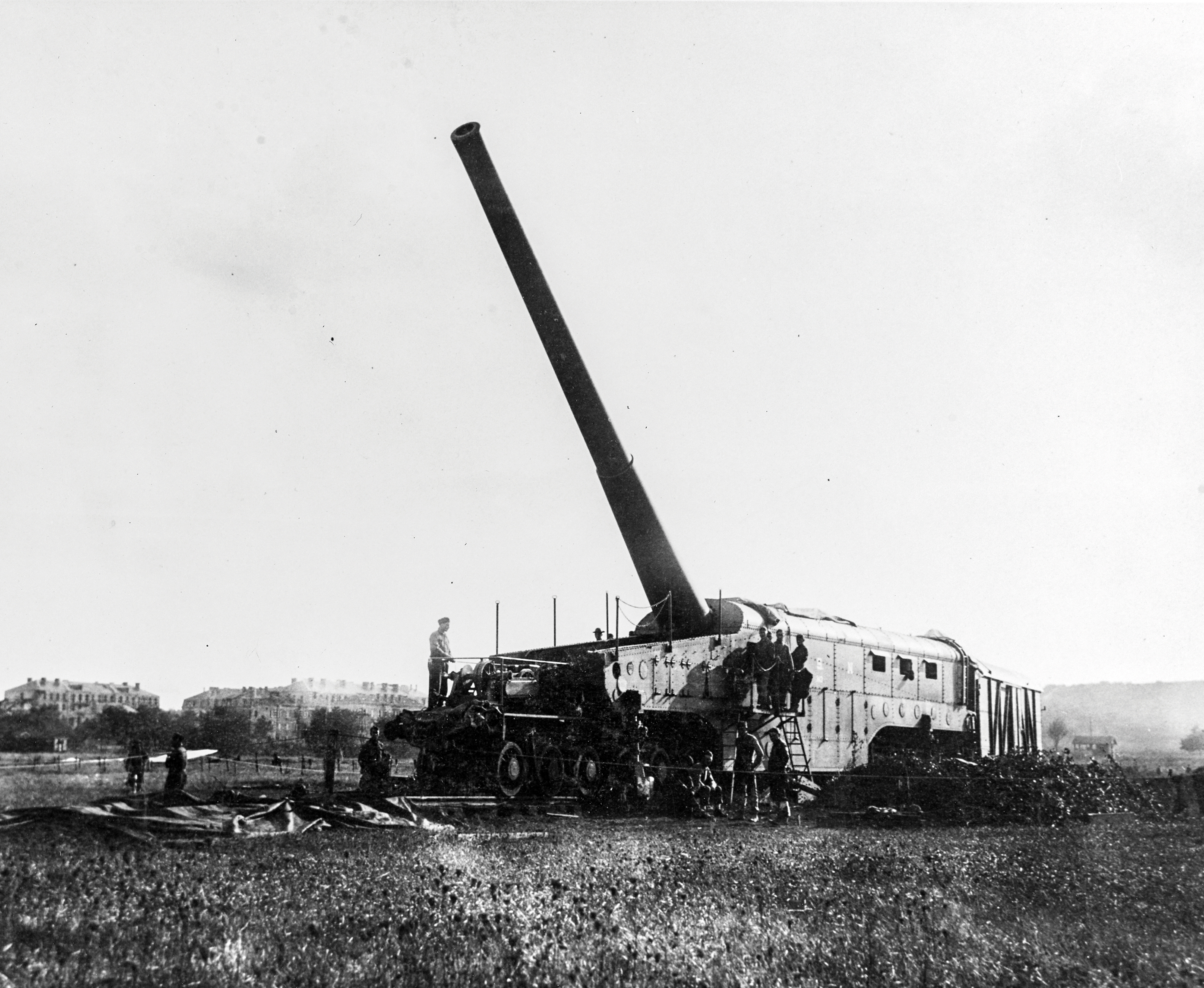

In September, the NHHC furthered its tributes beyond the web with an in-person commemoration of the U.S. Navy’s involvement in World War I by hosting a ceremony for the 100th anniversary of the first combat firing of the naval railway gun. The event took place at Admiral Willard Park at the Washington Navy Yard (WNY), where a World War I naval railway gun, still mounted on a railway carriage, is on permanent display.

While WNY personnel know the railway gun as a landmark where they work, many are unaware of its tie to the World War I victory. Upon entering the conflict in April 1917, the Navy already was developing long-range artillery guns primarily to counter the German Army’s heavy guns capable of bombarding the English Channel ports used by the Allies.

The Navy’s initial idea was to employ several 14-inch/50-caliber Mark IV naval rifles, with a complete train of equipment for each gun, on railway mountings behind British lines in France. However, changing military conditions prevented British authorities from definitively stating at which port these batteries were to debark. The Navy then offered the guns to General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, who readily accepted them.

As a result, in the summer of 1918, five U.S. naval railway guns made the journey across tahe Atlantic Ocean for use in France. Although they were assigned to the First Army’s Railway Artillery Reserve, the guns operated as independent units, run by sailors, under the command of Navy Rear Admiral Charles P. Plunkett.

The naval railway guns operated well behind the front lines and were not subject to the constant bombardment received by more forward positions, but the U.S. Navy railway batteries were hardly immune from enemy fire. Many of the units took counterfire from German artillery. German observation planes flew above their positions during the day, and bomber aircraft were active at night. While other battery personnel were wounded, the units lost only one sailor to enemy fire.

Retired Navy Rear Admiral Sam Cox, director of the NHHC, was the guest speaker for the commemoration ceremony and spoke about the importance of the railway guns and the Navy’s overall World War I mission.

“The U.S. Navy was able to provide a quick solution using guns that were normally intended for battleships,” said Cox. “The key point of the U.S. Navy’s participation in the war was that although we only lost about 430 sailors during the entire course of the war, we were able to get two million U.S. Army troops to France a lot faster than the Germans ever thought was possible. The Navy did this without any losses to U-boats, ending a war that at that point was the bloodiest in human history.”

—Mass Communication Specialist Second Class Destiny Cheek and Mass Communication Specialist Second Class Mutis Capizzi, NHHC