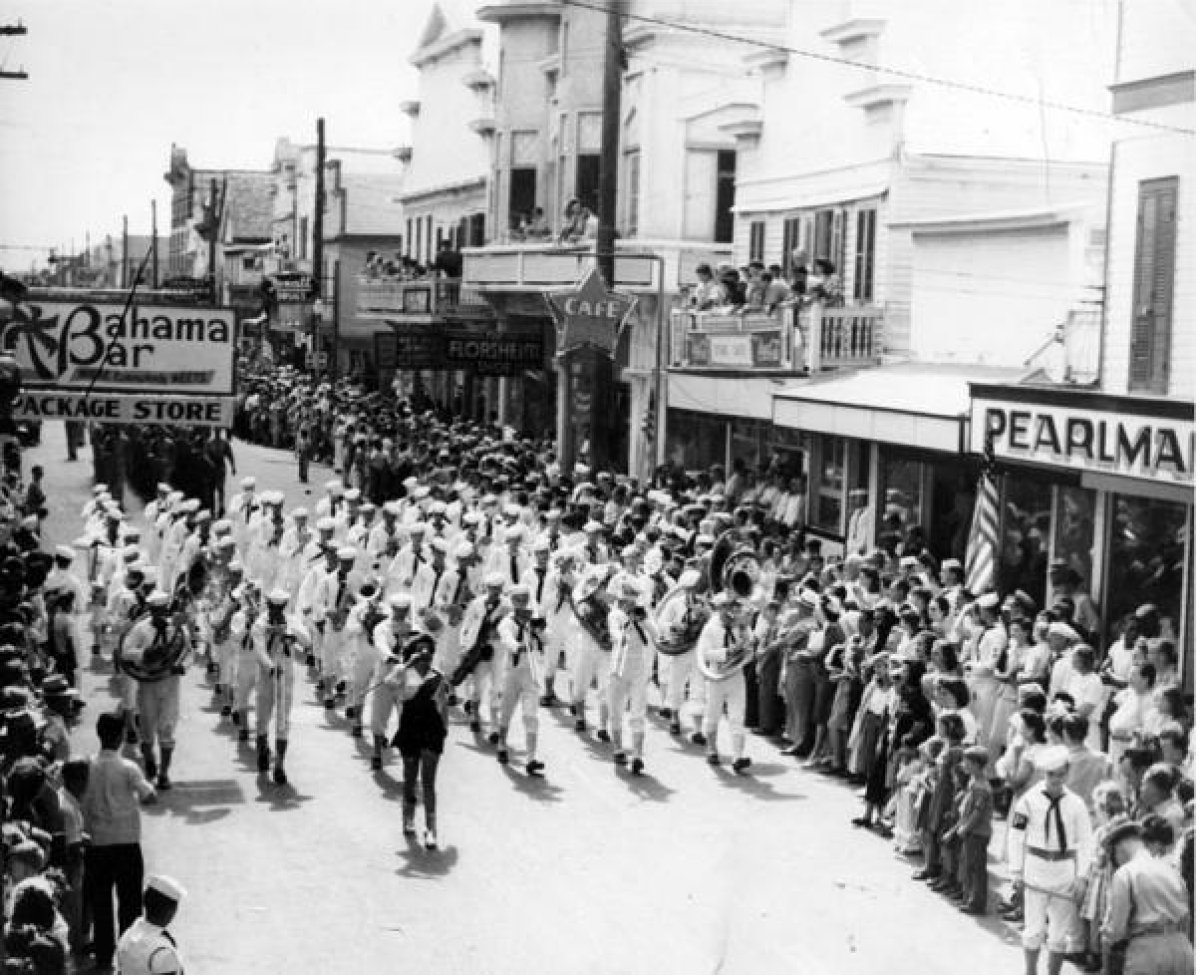

On 27 October 1922, thousands of Americans turned out across the country to catch a glimpse of their Navy. Ships visited ports from Maine to Miami and along the West Coast. A group of seaplanes from Pensacola trekked inland to Hannibal, Missouri, to showcase the potential of the Navy’s growing air arm. Radio stations set aside blocks of programming in support of Navy Day, and theater owners agreed to screen naval films to the public. Ingenious officers in Nashville even persuaded local restaurants to include pro-Navy messages in their menus and convinced some local ministers to reference Navy Day in their sermons. McClure’s magazine published a glowing piece on the wartime record of Admiral William S. Sims, and Sims himself wrote an article praising former President Theodore Roosevelt—whose birthday Navy Day was to celebrate—and his contributions to naval expansion. Navy Day 1922 proved extraordinarily successful at generating favorable publicity for the Navy and established a model for further Navy Days in the years that followed.

Navy Day was a partnership between the U.S. Navy and the Navy League, a civilian lobbying organization founded in 1902. Whereas the league had previously focused its energies at lobbying Congress, Navy Day represented a dramatic shift toward directly engaging with the American public. The league’s leaders, including its president, Robert W. Kelley, took credit for proposing the one-day publicity bonanza to the Navy’s leaders and for sponsoring the nationwide event. Sources, however, prove that Navy Day originated not with the Navy League but rather with a group of prominent Navy Department leaders, including Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt Jr., Rear Admiral William Veazie Pratt of the Navy’s General Board, and Director of Naval Intelligence Captain Luke McNamee. The Navy actively directed Navy Day celebrations while the Navy League provided political and public relations cover for their activities.

The Navy’s Public Relations Crisis

The U.S. Navy’s leadership went to extraordinary lengths putting together Navy Day in hopes of ending a three-year public relations crisis for the service. The postwar resumption of the construction of 16 capital ships authorized by the Naval Act of 1916, which promised to make the U.S. fleet “second to none,” so alarmed David Lloyd George’s government in Great Britain that it announced the “One Power Standard” in March 1920, committing his nation to matching U.S. construction. Japan, likewise fearing that a strong U.S. fleet could derail its plans for control of the western Pacific, announced the construction of eight battleships and eight battle cruisers in the fall of 1920.

The American public looked on the emerging arms race among the three wartime allies with increasing alarm because it seemed to repeat the balance of power politics that caused the Great War. Pleas for naval arms limitations found receptive ears among nearly every element of the American public and eventually forced President Warren Harding in July 1921 to call for an international conference to be held in Washington that November. The Washington Conference, which ended in February 1922, led to several treaties that halted the arms race and defused a number of potential conflicts. One of the treaties signed at the Conference, the Five-Power Pact, capped the size of the U.S. Navy and ended the decades-long expansion of the fleet (see “How Promise Turned to Disappointment,” August 2016, pp. 26–31).

To the Navy’s leadership, it seemed the service lost the battle because it lacked the tools to win an information war. To remedy the situation, Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby established the Information Section of the Office of Naval Intelligence in February 1922.

In League with the Navy League

Secretary Denby and others sought to reinvigorate the service’s relationship with the Navy League. In 1917, then-Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels banned all cooperation with the league after its leaders accused him of covering up union involvement in a fatal explosion at the Mare Island Navy Yard. This prohibition, combined with the dwindling public support for the Navy after the war, nearly crippled the league. Denby lifted the embargo in spring 1921. The league finally resumed public activities to lobby for a naval personnel bill in spring 1922, and its leaders sought new ways to collaborate with the Navy Department.

Assistant Secretary Roosevelt, too, had spent considerable time lobbying Congress against deep cuts to funding and personnel. A possible solution to congressional intransigence and public apathy appeared on 6 July 1922, when Mrs. William Hamilton visited Roosevelt in his office to plead for assistance for the New York Navy Club that her deceased husband helped establish. Her request to aid the club left Roosevelt unmoved, but the conversation inspired him to think of “a naval day for all the land” to promote the service. Days later, Roosevelt met with the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Hillary P. Jones; Commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Edward W. Eberle; Commandant of the Marine Corps Major General John A. Lejeune; and Rear Admiral Pratt. They agreed with the idea of a “naval day” but not what form it should take.

Roosevelt asked Pratt to review notes of both conversations and to draw up a plan. Pratt reached several important conclusions, including that any celebration should be linked to a historical event or person, but the date should occur in the fall due to weather and to avoid conflicts with fleet training. Pratt settled on 27 October, former President Roosevelt’s birthday, a suggestion with which his son reluctantly agreed. Pratt suggested a variety of actions for Navy Day: partnering with the Chamber of Commerce and other groups, declaring Navy Day a service-wide holiday, distributing the fleet along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, covering inland areas by sending ships up the Mississippi River, dispatching airplanes to local communities, and even staging a football game between Atlantic Fleet and Pacific Fleet sailors somewhere in the Midwest. Most important, he recognized that the Navy needed the league to propose the event because neither Congress nor the public would accept such a brazen act of self-promotion.

Roosevelt accepted Pratt’s outline, and the next step was finding an outlet to communicate this information to the Navy League. By summer 1922, Director of Naval Intelligence, Captain McNamee, had maintained a long correspondence with William Howard Gardiner, a retired utilities executive from a prominent Boston family who also had emerged as one of the league’s most energetic members. Gardiner had taken a keen interest in bolstering the Navy’s public image because he believed the public was not predisposed to hostility toward the Navy but rather lacked enough good, credible information about the value of the Navy to the nation. McNamee’s relationship with Gardiner provided the perfect outlet to surreptitiously pitch the plan to the league.

McNamee’s Bold Proposal

On 28 July 1922, McNamee wrote Gardiner a letter containing the bold proposal: There must be a “Navy Day” that would allow “the whole country pause for an hour and give serious thought to its Navy.” Such a day could help change the public’s perception of the service and, presumably, help counteract the prevailing negative opinions of the service that led to the Washington Conference. McNamee predicted dire circumstances should the Navy not improve its image, writing, “If we cannot sell the Navy to the people, it will not take long to start bankruptcy proceedings in Congress.”

Before outlining the plan, McNamee swore Gardiner to secrecy and insisted that the contents of the letter be shared only with Kelley, the Navy League’s president, and a few other high-ranking members. The plan must appear to have originated with the Navy League, McNamee reasoned, or Congress and the public would denounce the scheme as a blatant attempt at self-promotion. The letter then reprinted almost verbatim Pratt’s suggested list of Navy Day events.

Gardiner responded enthusiastically to McNamee’s proposal, saying it contained “FIRST RATE ideas.” McNamee provided Gardiner with detailed instructions on how Kelley should write to Secretary Denby to ask for permission to hold Navy Day, but Gardiner suggested McNamee ghostwrite Kelley’s letter of proposal as well as a response letter to be signed by Assistant Secretary Roosevelt. The available records do not indicate whether McNamee followed through on Gardiner’s ghostwriting suggestion, but a letter signed by Kelley was sent to the Navy Department on 29 August 1922 that allowed the formal public promotion of Navy Day to begin.

Although Kelley and others in the league put up money to promote Navy Day, the organization still lacked the finances to wage a full-throated promotional campaign. Gardiner continued to work despite this handicap and successfully persuaded Secretary Denby to assist the league’s promotional efforts by writing a five-page document outlining the historical context for the Navy’s development, its current missions, and its value to the nation. The Navy, Denby argued, provided for the nation’s defense, assisted in humanitarian operations, and served as a “training school for the youth of the country.” While the league’s participation gave the Navy the justification necessary to promote itself to the public, McNamee privately proclaimed that the Navy performed “most of the work” in ensuring that the celebration would be as grand as possible.

A Public Relations Success

The movement of ships attracted visitors in traditional port cities, but the Navy focused much of its attention on countering the anti-Navy sentiments more prevalent in the Midwest and other inland areas. Dispatching floatplanes to Missouri and the efforts of the officers in Tennessee certainly helped, but the Navy also relied on friendly media outlets for support. The pro-Navy Chicago Tribune editorialized that the public’s “unthinking optimism” had led to the degradation of the Navy and implored all “clear-headed Americans” to recognize the value of the service to the nation’s physical security and economic well-being. The paper also published an interview with General Board member Rear Admiral William Rogers that warned of the dangers of “unpreparedness” while reassuring the public that the Navy had no intention of building beyond the tonnage limits set by the Five-Power Treaty.

Navy Day was a noteworthy success in most areas, but the late start in planning limited the event’s effect in mobilizing public opinion. For instance, the solicitation of media support failed to prevent the editors of The Christian Science Monitor from condemning Navy Day as the “obtrusive advertising of war.” Elsewhere, a reservist in Worcester, Massachusetts, complained that Navy Day relied too much on the rehashing of war stories rather than providing more information about a “sailor’s life.”

These hiccups did not prevent the league and the Navy Department from collaborating on a larger and better-received Navy Day in October 1923, and the annual celebration survived the Great Depression and World War II. Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson canceled Navy Day in 1949 in favor of a unification-friendly holiday, Armed Forces Day. Still, Navy Day survived unofficially until 1972, when Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt worked with the Navy League to define the Navy’s official birthday as 13 October to celebrate the establishment of the Continental Navy.

The first Navy Day brought the service positive publicity at a desperate hour, yet the determination of the Navy to continue masking its overt public relations activities was an old habit that died hard. The leaders of the Navy Department and the league so successfully concealed the true origins of the celebration that it took decades to uncover enough pieces of the story of Navy Day for anyone to reconstruct its origins. The celebration heralded a shift toward a more active public relations presence from the Navy in the years after its creation. The Navy’s uniformed and civilian leaders never again took the support of the American public for granted as they had from 1919 to 1921, and Navy Day ultimately signaled that the service would remain engaged in the battle for the hearts and minds of the American people.

Sources:

Papers of Admiral William V. Pratt, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.

Armin Rappaport, The Navy League of the United States (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1962).

Record Groups 24, 38, and 80, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Theodore Roosevelt Jr., Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

William Howard Gardiner Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.