A Naval ROTC midshipman on summer cruise in Havana meets his literary idol.

It was a beautiful Cuban summer day in July 1955, and the searing heat of seductively beautiful Havana was overpowering. My Iowa-born shipmate and I cursed our hot, scratchy dress khaki uniforms, complete with regulation black neckties. We longed to change into the cool sailor’s whites worn at sea. Unfortunately, liberty privileges required all midshipmen to wear their “heat stroke khakis” ashore.

Our destroyer, the USS Hazelwood (DD-531), was tied up along with a half dozen other ships in Havana Harbor. The pre-Castro, Batista regime had thankfully relaxed a harbor ban previously invoked when a drunken sailor relieved himself on one of Havana’s statues of Jose Marti in March of 1949. The last word, however, seemed to have remained with the Cubans: our ship’s berthing assignment was only yards away from Havana’s gigantic main sewer discharge pipe.

Despite this, we were hopeful for a good day. One of my Dartmouth fraternity brothers, Luis Torroella, was a native son of Havana.1 Luis was planning on meeting us later that afternoon at his parent’s home, and would then drive us to Ernest Hemingway’s Cuban estate, “Finca Vigia,” or Look-out Farm.

Our plan was simple and naïve: We were two English majors on a quest to meet the world-famous author and recipient of the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. We were going to knock on Hemingway’s door, Navy hats in hand, and hope for the best.

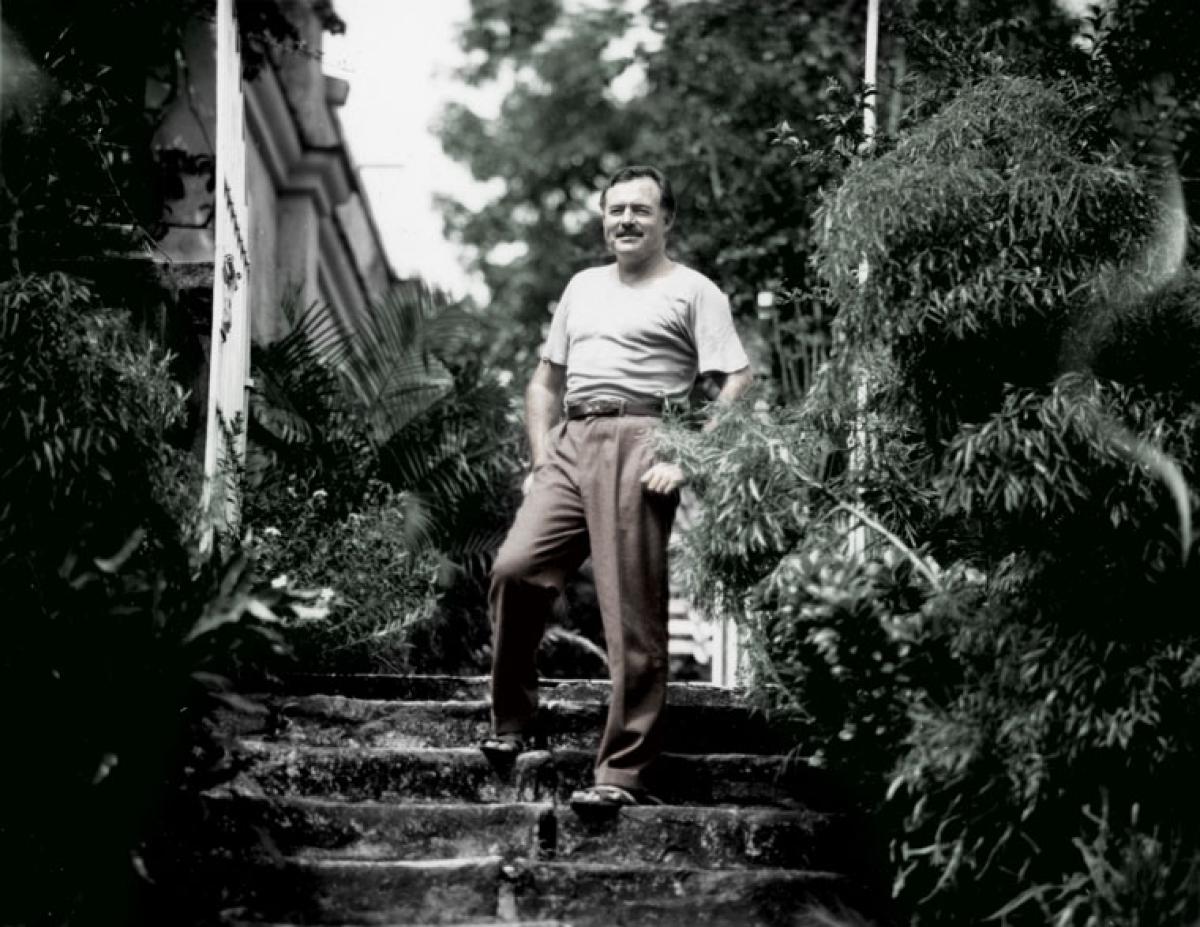

Finca Vigia lay a half hour outside Havana in a semi-rural enclave. It was a large, somewhat sprawling but handsome old structure of dignified presence atop a steep hill. Thick plantings of banana trees and assorted exotic flora provided a screen from the road. It was also, we discovered, well-fenced and gated.

Luis left us standing at the locked gate, taking the car with him. Nearby were clusters of small houses that are part of the community of San Francisco de Paula. A man suddenly appeared in the open doorway of one of the homes.

“Senor Hemingway not home. Gone to airport to pick up Senora,” he shouted across the road.

“Gracias, Senor,” we replied.

“Back maybe couple hours. Maybe three or four.” There was a look of concern on his weathered face.

“You guys look hot as hell! Come in! Have a cold cerveza.”

We entered and settled on a worn couch to experience once again the limitless Cuban hospitality we had been receiving everywhere.

A radio was broadcasting a baseball game with high excitement, and a small fan was working hard in a corner. Cold beers were presented with a smile, and we raised our bottles gratefully. “Gracias. Muchos gracias, Senor!”

Two hours later, the baseball game was still ongoing but we rose to say goodbye. Our generous host glanced out the open doorway. “Senor Hemingway here! You guys hurry!” With a quick handshake and thanks we rushed outside, arriving just as the chauffeur swung open the gate.

A gorgeous red open-top Chrysler convertible idled powerfully in the drive. Seated in front in the shotgun seat, his wife to his left, was the unmistakable man himself.

“Sir! Please excuse us, but would it be possible to have a quick visit with you?”

He shook his head. “No, I’m sorry boys, but I’ve got to be up early in the morning to work.” We were silent and crestfallen after waiting for so long. He hesitated. A little longer. “Okay, hop in the back.”

Mary Hemingway instantly fixed us with an angry glare. “Why can’t you people ever leave us alone!” We mumbled an apology.

Hemingway said nothing but there was a set to his shoulders.

A book lay on the rear seat, and Hemingway noticed it. “Are you reading that?” he asked, interested. “No sir, I believe your wife?” She reached for it, the glare undiminished.

At the top of the hill the chauffeur pulled up at the bottom of wide, whitewashed steps that led to the smaller steps of the portico entrance. As we climbed, I noticed many small weeds growing through the rear joints of the steps. They were flowering, only marginally pretty, and still definitely weeds. The surrounding landscaping appeared orderly.

What a curious anomaly, I thought to myself, marring the entrance to a beautiful and well-situated home.

Mary Hemingway marched ahead of us and disappeared, not to be seen again. In the Finca’s foyer there was a champagne bucket filled with nearly melted ice and a bottle awaiting the master’s return. Hemingway looked at us. “How about some champagne, boys?”

Inside the living room were centered two large, comfortable-looking adjoining chairs. One of them had a stand alongside the left chair arm which contained a selection of whiskey, gin, cocktail mixers, and sparkling clean glasses. On the other chair arm a book lay spread open, the paperback edition of Viking’s The Portable D. H. Lawrence with the rising orange phoenix on the cover. I got a thrill, for I coincidentally also was reading the same edition.

Hemingway sat in his chair, and we seated ourselves in two low-slung chairs that faced him. I started to ask a question about Lawrence, but the champagne was being poured. We raised our glasses in appreciation for the second time that day.

“Thank you, sir.”

“You are welcome, gentlemen.”

The room was bright and airy with long bookcases under the windows. The opposite wall displayed a number of mounted, horned African animals, most of which I didn’t recognize aside from several elegant looking impalas. Many lovely paintings hung beneath the trophies. Lower bookcases several feet high sat beneath them.

The man seated before us was a big man, big-chested with a boxer’s faded physique. He was noticeably aging with several prominent forehead scars from the back-to-back African plane crashes a year before. Nonetheless, he was strikingly handsome with perfect features. The famous white beard was trimmed quite short, and he had a great, natural presence about him.

But the eyes were the thing. They were extremely intelligent and aware. There was also a sensitivity—sometimes almost a shyness—projected. I now believed I understood why those desperately blossoming weeds were spared. Beauty of whatever shape it may be, or whatever form it may take, must have been important to this man.

We drank our champagne. He was practiced at putting the awestruck at ease, asking where we went to college, did we like it, what we studied, and were we enjoying Havana? He listened intently to our replies. I forget to ask about D. H. Lawrence, but I did mention J. D. Salinger. He said Salinger was working on The Catcher in the Rye during World War II when they met. Perhaps incorrectly, I sensed he didn’t care for the book. I wanted to weigh in with my own negative opinion, but thought better of it.

The bottle of champagne was too soon empty and it was time to consider leaving. I asked him if we could have his autograph and he fished out a small notebook from his clean, white guayabera shirt. Would he mind signing mine and include his mailing address? He looked at me, a trifle irritated, but still did a careful printing of the mailing portion. He then surprised us.

“How about a tour of the house before you go?”

We walked past more walls of mounted animal trophies, some of which appeared western American in origin. We passed more lovely paintings, passed an old Spanish bullfight poster with a 1920s look, passed through the main library with thousands of books, through his writing room where a fierce-looking South African cape buffalo peered down on his vanquisher.

We continued on through a corridor near the kitchen where quite out of sight of prying eyes hung Joan Miro’s splendid (and valuable) painting “The Farm.” A few more turns and we reached a bedroom with a fully made king-size bed, totally covered with stacks of rubber-banded letters, many with foreign stamps. Many appeared unopened. Each carefully packed pile was about 10 inches high. He pointed and quietly said to me, “As you can see, I get a lot of mail.” (And I got the message.)

“Do you boys have a way to get back to the ship?” We did not. “I’ll have Rene drive you back.” We thanked him for that, and for his wonderful hospitality.

At the doorway I turned and decided to risk one more question. “Sir, would you mind telling us why you changed your mind about our visit?

There was no hesitation. “People were very good to me when I was your age.”

We said goodbye, shook his firm hand and again piled into the back of the big red Chrysler.2 It was a refreshing, breezy ride back to the docks, and Rene enjoyed the opportunity to power the car up to speed – and beyond. “Gracias, Rene!” “Okay, amigos!”

The Hazelwood lay calm and floodlit in the distance. We saluted and asked permission to come aboard. Granted. We went below deck to our bunks in the stifling hot fantail where we compared impressions of this kind and generous man who happened to be one of the world’s greatest writers.

The final, shocking event in July 1961, when Hemingway took his own life, only deepened our appreciation of the privilege given us that special day.

1. Six years later, in 1961, Fidel Castro was firmly in power in Cuba. Luis Torroella was to be captured in a garage just outside Havana’s Ciudad Deportiva Stadium and identified as the as the leader of a group of counterrevolutionaries. He was charged with a plot to assassinate Castro. Bazookas were mounted on a Jeep to be assisted by hand grenades thrown from the sidewalk as Castro was being driven to the stadium. The Castro regime accused the CIA of providing the weapons and masterminding the plot. Luis is believed to have been immediately executed.

2. The car was located in 2011 battered, rusted out, and unrecognizable. Hemingway had bequeathed it to his doctor and good friend when he left Cuba for the last time. The Chrysler had been passed down to the doctor’s son and a line of subsequent owners until it was derelict and abandoned. It is now at the Museo de Hemingway awaiting restoration.