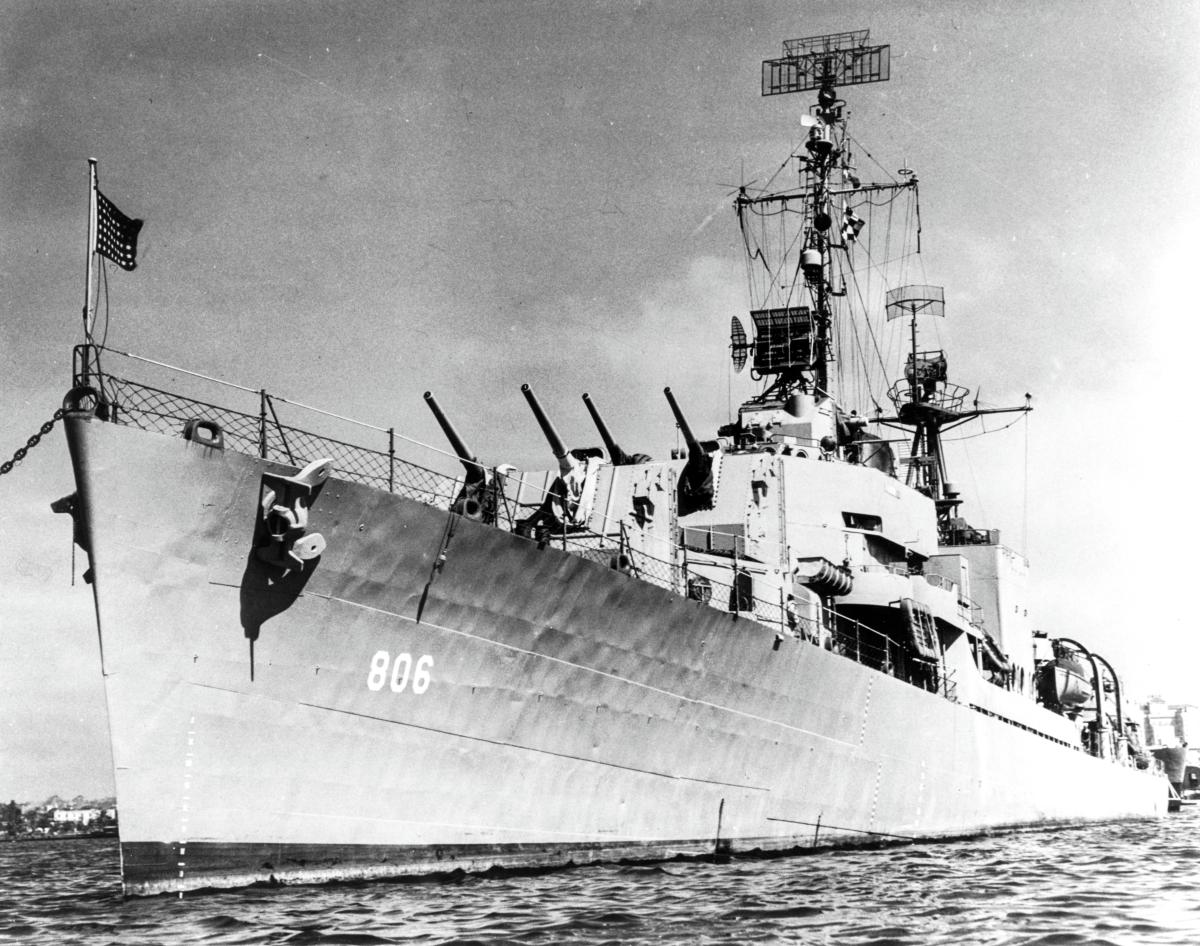

On 13 November 1944, for the first time in history, the U.S. Navy named a warship after a woman: Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee, the second superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps (NNC) and first woman to receive the Navy Cross. The destroyer, the USS Higbee (DD-806), mirrored her namesake’s resilient, unwavering, and energetic nature, earning an unprecedented eight bronze battle stars in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.1

The real-life Higbee was a pioneering and devoted nurse who joined the Navy in 1908, when women generally were unwelcome, underpaid, and denied official rank. Over the next 14 years, she nevertheless rose to become the superintendent of a fledgling nurse corps and directed its evolution from infancy to permanence. She also recruited, trained, and managed thousands of nurses during two of the 20th century’s worst humanitarian crises: World War I and the influenza pandemic of 1918. Higbee institutionalized the role of women nurses in military medicine; established the NNC as a professional, battle-hardened, and accepted part of the naval service; and advanced the status of women in the military. Together, her accomplishments altered the course of U.S. military history and contributed to the nation’s readiness and warfighting capabilities.

One of the Sacred Twenty

Lenah Sutcliffe was born in 1874 in Chatham, New Brunswick, Canada, and immigrated to the United States after finishing formal schooling. In 1899, she completed nursing training at the New York Postgraduate Hospital and began working as a surgical nurse.2 She later married retired Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel John Henley Higbee and could have lived a comfortable and conventional life as a nurse and wife had two events not intervened: Her beloved husband passed away on 18 May 1908, and almost simultaneously, President Theodore Roosevelt signed a naval appropriations bill authorizing the establishment of a nurse corps.3 Higbee’s new status as a widow allowed her to apply to the NNC, which required applicants to be 22 to 44 years old and unmarried.4

Why Higbee chose to join the Navy is unclear, but it could not have been because it was easy. She submitted a formal application with references from mentors and military acquaintances she had met through her late husband.5 Her supporters included nursing superintendents and physicians from prominent New York hospitals, who praised Higbee’s “executive ability,” “attractive personality,” and “sincere interest in her work,” as well as retired Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce, who deemed her “thoroughly competent to discharge the duties of the position for which she applied.”6 At her own expense, Higbee traveled to the naval hospital in Washington, D.C., where she took—and passed—both oral and written examinations. On 1 October 1908, she became one of the first 20 official female members of the NNC, a group that came to be known as the “Sacred Twenty.”7

Nurse Higbee and her peers encountered institutional discrimination almost immediately. Unlike male physicians and hospital stewards, the nurses were not granted a formal rank and were paid considerably less. “There were no quarters for them,” recalled fellow nurse Beatrice Bowman. “They rented a house and ran their own mess. These pioneers were no more welcome to most of the personnel of the Navy than women are when invading what a man calls his domain.”8

Following a rigorous five-month course of study covering subjects from naval hygiene to naval etiquette, an unexpected opportunity arose for Higbee.9 In the spring of 1909, Surgeon James Leys, commanding officer of Naval Hospital Norfolk, Virginia, initiated an urgent request for additional staff. The Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) responded by assigning nurses. On 14 April, Higbee was promoted to chief nurse and dispatched to Portsmouth. When she and two of her colleagues reported for duty, Leys was appalled. He expected male corpsmen and did not believe women could work in a hospital with no female patients.10 Undeterred, Higbee worked seven days a week and set Leys’ concerns to rest. Her fitness report, completed several months after her arrival, noted she performed “intelligently and to the satisfaction of [her commanding officer],” with “harmonious” relations.11 In effect, Higbee and the Navy were a match.

Superintendent of the Nurse Corps

In 1911, the first NNC superintendent resigned, and Chief Nurse Higbee was appointed as her successor, overseeing 86 nurses stationed in the United States, the Philippines, and Guam. Her first order of business on reporting to BUMED was to improve working conditions for the Navy’s nurses. She crusaded tirelessly to obtain proper living quarters for them. She also lobbied for equitable pay. Nurses were receiving just 40 cents for daily subsistence, plus lodging, whereas men received 75 cents.12 This was a financial hardship that forced many nurses to seek employment elsewhere, a vexing problem for the Nurse Corps throughout Higbee’s tenure.

Higbee also took up the cause of healthcare for military dependents. Naval hospitals at the time had capacity only for active-duty service members, which became “a subject of much correspondence between the superintendent and chief nurses” and “the Surgeon General and numerous commanding officers.”13 In large part because of her efforts, BUMED eventually obtained funding to increase the size of healthcare facilities and the scope of services offered to dependents.

Planning for War

In 1914, the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand plunged Europe into World War I. Though the United States remained neutral, Higbee saw the need to prepare. Between 1915 and 1917, she served on numerous executive healthcare committees, with a special focus on the National Committee of the Red Cross Nursing Service. The committee saw an impending need for military nurses and facilitated the direct recruitment of 25,000 nurses, most of whom matriculated to the Army.14 “For two years prior to our actual entering into this conflict, warnings had been sounded and such tentative preparations as were possible had been made by those who were wise to the significance of war signs,”Higbee later remembered.15 Between April 1917 and November 1918, she oversaw the expansion of the NNC from 160 to 1,386 nurses.16

Under Higbee’s leadership, the roles and mission of the NNC evolved. At her recommendation, in 1913 nurses had been assigned to the transport ships USS Mayflower and USS Dolphin.17 During the war, Higbee also coordinated nurses to serve transport duty on board the SS George Washington, SS Leviathan, and SS Imperator.18 The fleet’s anxiety and initial resistance to the presence of female nurses on board again proved unfounded; the women’s conduct and performance at sea were outstanding and probably contributed to the subsequent and permanent assignment of nurses to hospital ships.19

In 1915, Superintendent Higbee steered the NNC to begin training hospital corpsmen. Her intent was not only to assist in the teaching of “nursing methods” but also to “develop in the hearts and minds of these ‘pupil nurses’ the principles of conscientious care of the sick.”20 Between 1916 and 1918, the Navy and Marine Corps’ ranks swelled from 71,000 to 501,000. There were sufficient corpsmen to care for those deployed in harm’s way in large part because of Higbee’s training initiative.

While preparing the Nurse Corps for World War I, Higbee also closely managed nurses deployed to numerous Pacific and Caribbean islands. In these remote locations, her nurses pioneered humanitarian and global health outreach programs to train local women to become nurses.

World War I

When the United States finally declared war on Germany in 1917, 8,000 Red Cross nurses already were trained, immunized, and ready for immediate mobilization. Without delay, 339 of them were assigned to naval hospitals and 540 to Navy detachments.21 BUMED mobilized base hospitals to support the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France, Scotland, Ireland, and England. Each unit deployed with a complement of 30 to 60 nurses.22

Alongside doctors and medics, Higbee’s nurses triaged and treated injuries that “were deeper and more extensive” than ever previously encountered.23 The complexity and severity of injuries from “shrapnel and high velocity projectiles” were “such that [the nurses] never imagined it possible for a human being to be so fearfully hurt and yet be alive.”24 Along the 550-mile Western Front, the realities of warfare included “trench foot, disease, rats, vermin, and an absence of rudimentary hygiene,” along with the horrifying results of “mustard, phosgene, and chlorine gases.”25 Nurses also confronted post-traumatic stress disorder, then known as shell shock. To better prepare new nurses for the realities of 20th-century warfare, Superintendent Higbee oversaw the development of the Vassar Training Camp, which served as the first operational nurse training school.26

Overseas, Higbee’s nurses “faced raw, cold weather and shortages of water for bathing and laundry, long hours at work and little privacy or time off.”27 At the time, Higbee affirmed, “No words of mine can adequately describe the valiant way the nurses met [such] austere and dangerous conditions.”28

Higbee’s NNC received recognition from General John J. Pershing, commander of the AEF, all the way down to unit commanders, who highlighted the “self-sacrifice which this noble body of women rendered.”29 By the end of the war, one newspaper concluded “the most needed woman [was] the war nurse” and defined her as “a soldier, fighting pain, disease and death with weapons of science and skill.”30

Influenza Pandemic of 1918

The November 1918 Armistice did not extinguish the challenges facing Superintendent Higbee and her corps. Earlier that year, a mysterious viral illness began spreading through Europe and the United States. The influenza pandemic of 1918 ultimately killed as many as 50 million people. In the United States, the average life expectancy was reduced by 12 years.31

Higbee and her nurses transitioned from treating the carnage of industrial warfare to battling a global health disaster. At home and abroad, chief nurses routinely had a thousand patients under their supervision.32 The Navy alone “recorded 5,027 deaths and more than 106,000 hospital admissions for influenza and pneumonia out of 600,000 men.”33 Influenza rendered “the Army and Navy non-effective and diverted resources, personnel, and scarce human attention and energy from the military campaign,” highlighting the necessity for nurses.34

In recognition of the NNC’s contributions to readiness during the war and the influenza pandemic, the Navy permitted nurses to wear the Victory Medal.35 On 11 November 1920, Superintendent Higbee received the Navy Cross for “distinguished service in the line of her profession and unusual and conspicuous devotion to duty as superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps.”36 She was the first woman and only living nurse to receive the honor; three other nurses who succumbed to the flu were awarded the honor posthumously.37

Postwar Era

After the war, Superintendent Higbee continued to shape the NNC. She finally achieved a pay increase “from $50 to $60” per month—still not even with male counterparts but an improvement.38 She also formalized Navy nursing uniforms bearing the golden oak leaf and acorn superimposed over an anchor.39 She promoted legislative efforts to improve the professional education of nurses.40 When the new Veterans Bureau emerged in 1921 and reserved a limited number of naval hospital beds for veterans with chronic medical and neuropsychiatric illnesses, Higbee quickly supported the initiative and assigned nurses despite dwindling resources following demobilization.41

During her entire tenure, Higbee devoted tremendous energy to promoting and shaping the reputation of the Nurse Corps. She published extensively in professional journals, detailing the accomplishments, promotions, and new assignments of the NNC. In 1921, she authored a five-page article outlining her high regard for the naval service and the military necessity to attract only the highest caliber nurses.42 Higbee consistently encouraged her nurses to strive for improvement, asserting that “no greater danger can come to a nurse than contentment with easy duty and the belief that the completion of her course of training is the final goal.”43

At her own request, and desiring “to take up other work,” Higbee was honorably discharged on 30 November 1922.44 Reflecting on her naval career, she concluded that Navy nurses “must have an open mind, must encourage deep interest in the Naval Service and must possess the common sense to realize that adaptability necessary for success must be in the individual since a Military Service cannot adapt itself to a person or persons.”45 She exemplified this statement throughout her military service, blending practicality with optimism in a way that enabled her and her subordinates to excel.

An Essential Contribution

In 1941, Higbee passed away and was interred at Arlington National Cemetery beside her husband. The following year, Navy nurses were granted “relative rank,” and in 1944, finally garnered “full military rank” with equal pay.46

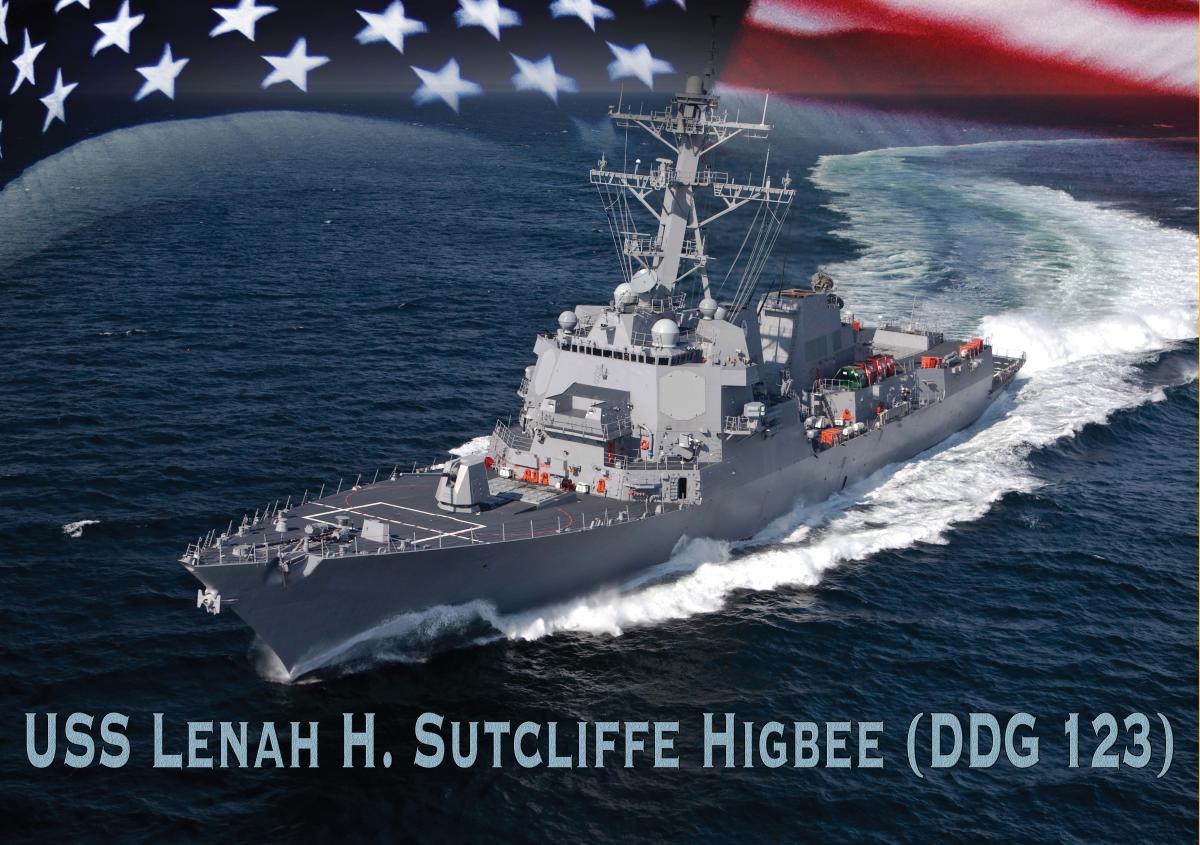

While Higbee’s contribution will never be measured by the number of enemy combatants killed or ships sunk, her efforts directly equated to nurses deployed, corpsmen trained, lives saved, and service members returned to the fight. She effectuated the “realization that an adequate nursing force is as essential to victory as any other military factor.”47 In 2016, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus made an unprecedented announcement in the planned commissioning of another USS Higbee (DDG-123) in 2024. Given Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee’s contribution to the Nurse Corps, Navy, and nation, the honor is well deserved.

1. NavSource Naval History, “Welcome Aboard Packet, USS Higbee (DD-806)—Vital Statistics,” NavSource Destroyer Archive, 1973.

2. Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), “Devotion to Duty: Four Nurses Receive Navy Cross in 1920,” U.S. Naval Institute Naval History Blog, 11 November 2014.

3. David F. Winkler, “The ‘Sacred 20’ Launched U.S. Navy Nurse Corps,” Seapower 51, no. 5 (May 2008), 55.

4. Sheila G Llanas, Women of the U.S. Navy: Making Waves (North Mankato, MN: Capstone Press, 2011), 9.

5. Lenah S. Higbee, Letter to Superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps, 25 August 1908, U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Archives.

6. Annie Rykert, Letter to Rear Admiral Presley Rixey, circa 1908; Annie Goodrich, Letter to Rear Admiral Presley Rixey, 2 June 1908; Westray Battle, Letter to Doctor Rixey, 22 July 1908; Stephen B. Luce, Letter to Surgeon-General Presley M. Rixey, 28 May 1908; and Henry Erben, Letter to Surgeon-General Presley M. Rixey, 7 June 1908 U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Archives.

7. “1908: Navy Nurses and the Nurse Corps.” U.S. Naval War College, Naval Historical Collection.

8. Andre B. Sobocinski, “The ‘Sacred Twenty’: The Navy’s First Nurses,” Navy Medicine Live, 11 May 2012.

9. U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, “Navy Medicine —‘The Sacred 20,’” Navy Medicine History Slideshow.

10. Sobocinski, “The ‘Sacred Twenty.’”

11. “Efficiency Report U.S. Navy Nurse Corps at U.S. Naval Hospital Norfolk – Chief Nurse Lenah Higbee (16 April 1909–30 June 1909),” 3 July 1909, U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Archives.

12. Dorris Sterner, In and Out of Harm’s Way: A History of the Navy Nurse Corps (Seattle, WA: Peanut Butter Publishing, 1997), 36–37.

13. Dermott Vincent Hickey, “The First Ladies in the Navy: A History of the Navy Nurse Corps, 1908–1939,” master’s thesis, George Washington University (June 1963), 57.

14. Hickey, “The First Ladies in the Navy,” 57.

15. Lenah Higbee, “Work of the Navy Nurse Corps,” Proceedings of the Twenty Fifth Annual Convention of the National League of Nursing Education, 24–28 June 1919 (Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins, 1919), 127.

16. U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Biography Archive, “Official Biography of Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee, Nurse Corps, USN, Second Superintendent (1911–1922).”

17. Sterner, In and Out of Harm’s Way, 37.

18. Hickey, “The First Ladies in the Navy.”

19. “Surgeon General’s Annual Report (1919),” Navy Department Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919), 11–12.

20. Lenah S. Higbee, “Navy Nurse Corps,” The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 66, no. 1 (January 1921), 223.

21. Portia Kernodle, The Red Cross Nurse in Action, 1882-1948 (New York: Harper Publishing, 1949), 110.

22. “Surgeon General’s Annual Report (1918),” Navy Department Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (Washington Government Printing Office, 1918), 11; and Hickey, “The First Ladies in the Navy.”

23. Deborah M. Judd. “Nursing in the United States from 1900 to the Early 1920s,” chapter 5 in A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2010), 82.

24. Alice Fitzgerald, “To Nurses Preparing for Active Service,” American Journal of Nursing 18, no. 1 (October 1917), 188.

25. Jan Herman and Andre Sobocinski, “Echoes of Navy Medicine’s Past, Part IV: Navy Medicine in the ‘Great War’ and Inter-War Years, 1917–1941,” Navy Medical Department History Blogspot, 1 January 2012.

26. U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, “Navy Medicine—‘The Sacred 20,’” Navy Medicine History Slideshow.

27. “Military Nurses in World War I,” Women in Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, History and Collections, 16 July 2016.

28. Higbee, “Work of the Navy Nurse Corps,” 129.

29. Jane A. Delano, “Greater Love Hath No Man,” American Journal of Nursing 19, no. 1 (October 1918), 188.

30. “Call For Red Cross Nurses Most Urgent,” The Sun, section 5 (9 June 1918).

31. Bryan Walsh, “Solving the Mystery Flu That Killed 50 Million People,” Time, 29 April 2014.

32. Lenah S. Higbee, “Navy Nurse Corps,” The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 66, no. 1(January 1921), 58.

33. Carol R. Byerly, “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919,” Public Health Report 2010, 125 (Suppl. 3), 83.

34. Byerly, “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic,” 83.

35. Higbee, “Navy Nurse Corps,” 58.

36. “Awarding of Medals in the Naval Service, Hearing Before a Subcommittee on Naval Affairs United States Senate, Sixty-Sixth Congress” (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920), 160.

37. Naval History and Heritage Command, “Devotion to Duty: Four Nurses Receive Navy Cross in 1920,” U.S. Naval Institute Naval History Blog, 11 November 2014.

38. Hickey, “The First Ladies in the Navy,” 73.

39. Higbee, “Navy Nurse Corps,” 82.

40. Higbee, “Navy Nurse Corps,” 444.

41. Lenah S. Higbee, “Nursing in Government Services Second Paper,” American Journal of Nursing 22, no. 7 (April 1922), 524–525.

42. Higbee, “Navy Nurse Corps,” 221–225.

43. Higbee, “Work of the Navy Nurse Corps,”134.

44. “The Navy Nurse Corps,” Journal of the American Medical Association 79, no. 25 (16 December 1922), 2096.

45. Lenah S. Higbee, “Nursing as it Relates to the War: The Navy,” American Journal of Nursing 18, no. 1 (October 1917), 1063.

46. Sobocinski, “The ‘Sacred Twenty.’”

47. “Call For Red Cross Nurses Most Urgent.”