Allied and Axis forces constantly jockeyed for advantage during the World War II Battle of the Atlantic, not only over weaponry and tactics, but also over technology and information. The Imitation Game, a 2014 Academy Award–winning film, depicted iconoclastic British mathematician Alan Turing’s efforts to unravel Germany’s Enigma cipher system, which enabled British intelligence to capture top-secret “Ultra” intelligence data. The film’s screenwriters altered names and events but also shortchanged a related American story. The Kriegsmarine Enigma confounded Bletchley Park for much of the war, blinding it to vital information on U-boat operations. When the Battle of the Atlantic finally reached American shores, Howard T. Engstrom, a U.S. Naval Reserve commander, employed cutting-edge computing technology to help tame Enigma.

Explaining a Puzzling Device

Enigma was actually an unprepossessing but devilishly clever cipher machine conceived after World War I and sold commercially during the 1920s. (Ciphers replace plain-text letters or numbers according to specific procedures. Codes, by contrast, substitute words, letter groups, or numbers.) Eventually, Germany saw the military value of this inexpensive battery-operated device (similar in appearance to the earliest Apple computer) housed in a varnished oak box with a hinged lid.

Enigma’s three-tiered, 26-letter keyboard (with no numerals or punctuation marks) resembled that of a typewriter. But Enigma also featured a panel with alphabet letters repeated in the same order as the keyboard. Behind each panel letter was a tiny light bulb. As a code sender pecked at the keyboard one letter at a time to create an enciphered message, the device scrambled each letter into another that appeared, illuminated, on the panel. (A typed “B,” for example, might show as an “S.”) When a code receiver, sitting at an identical Enigma, typed in the coded message (radioed in Morse code), the deciphered letters lit up on the receiver’s panel.

Enigma’s technological essence involved routing electrical impulses from the keyboard to the light panel by as complicated a path as possible. The rerouting mechanism consisted of three shaft-mounted rotating discs (rotors), each three inches in diameter. Both sides of each rotor were fitted with 26 electrical contact points. When the sender struck a letter on the keyboard, the first rotor on the right revolved, or “stepped,” 1/26th of a revolution, much like an odometer. The contact points with the other rotors thus changed completely, creating entirely new entry and exit paths. After 26 letters had been struck, the second, or middle, rotor clicked in. After the next 26 letters, the third rotor began turning.1 A fourth and final fixed rotor (a “reflector” or “mirroring commutator”) rerouted the current back through the first three rotors, ensuring the plain and scrambled texts were always reciprocal.2

Because the removable rotors could be reordered on the shaft and each rotor could be set individually to start revolving from any one of the 26 different positions, electrical contact-point possibilities were astronomical. But to increase Enigma security even more, the Germans added another encryption feature: a Stecker (plug) board at the front of the machine, consisting of lettered holes. Pairing plug holes electronically using telephone switchboard–type cable enabled swapping individual letters (“A” became “E,” for instance, and vice versa), supposedly raising encryption possibilities beyond mathematical reckoning.3

Enigmas were easily operated, and coders and decoders both followed prearranged “keys”—codebook instructions establishing the wheels to be used and the order and angle of their placement. German military cryptologists confidently assumed Enigma messages were unbreakable, but operator habits and routine message contents proved weak points. By guessing at fragments of plain text (later called “cribs”—English school slang for information obtained by cheating) and leveraging that knowledge to determine keys (much the way passwords are hacked today), Polish military cryptographers were able to decode a large volume of German signal traffic.4

By tweaking Enigma procedures, the Germans occasionally “blinded” their adversaries, but the Poles countered with an ingenious automated contraption called a “bomba,” so-named, some sources say, because of the ticking noise it made.5 A bomba was essentially a linked series of Enigma rotors that could be used systematically to “try” combinations of encrypted letters. Bombas could not decode transmissions, but they could eliminate vast numbers of impossible Enigma key combinations. In August 1939, though, with war approaching and German Enigma practices growing ever more sophisticated, the Poles turned over all their research, materials, and military Enigma devices to the British.6

This gift saved British intelligence much work, providing the foundation on which Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman, two Cambridge mathematicians, began designing more powerful electromechanical bombas—soon called “bombes.” Initially, however, Brits at Bletchley Park’s Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) relied heavily on laborious statistical tabulation methods. And while they had some success breaking the Luftwaffe Enigma, they were totally stymied by the Kriegsmarine Enigma, which was operated with tighter communications discipline and more intricate setup procedures.

That said, in all of their work, much of it compartmentalized according to service arms and methods, the British somehow avoided interservice rivalry. Everyone shared equally in all phases of the operation without a single leak. When it came to sharing with their American allies, however, GCCS was not so forthcoming.

Misgivings Between Friends

In December 1940, as the British-American alliance deepened, government officials agreed to share cryptology breakthroughs. But, even as planning began for a February 1941 exchange visit to Britain, both nations harbored misgivings.

The U.S. Army and Navy approached the visit with different agendas. The Army’s cryptology guru, William Friedman, devised a gift list that included the Purple machine, an analog device used to crack Japanese diplomatic messages. For his part, Rear Admiral Walter S. Anderson, head of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), hinted the Navy might not participate at all.

In the end, both service arms sent junior people lacking deep mathematical or cryptology skills. But the Army did deliver the Purple analog, a time-tested device. Reciprocity on Enigma, though, was another matter. Permission to show Enigma to the Yanks was withheld until the end of their stay, and what they saw revealed Bletchley’s skimpy progress. Its first generation bombes still depended on old-fashioned cryptology, and it would be months before GCCS finally made real progress on the Kriegsmarine Enigma. That breakthrough came on 9 May 1941, when a British destroyer boarding party retrieved a trove of codebooks, signal logs, and even a working Enigma machine from the abandoned and sinking U-110.

In America, meanwhile, Commander Laurance Safford, the U.S. Navy’s senior code-breaker and the head of OP-20-G, the U.S. Navy version of GCCS, concluded that he would need to solve the Kriegsmarine Enigma on his own. Unfortunately, OP-20-G personnel attacked Enigma the hard way, trying to divine its inner workings without access to the machine or any decrypted messages. That August, Commander Alastair G. Denniston, the congenial 63-year-old Scot who headed Bletchley Park, visited OP-20-G, intent on mending fences but also on dissuading the signals intelligence and cryptanalysis group from building its own Enigma deciphering device.7 Denniston apparently got a cold shoulder, and Safford’s personnel soldiered on with no prospect of success.

Efforts Intensify

Among the reverberations from the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor was a shake-up in which control of OP-20-G passed from ONI to the Office of Naval Communications (ONC). Under the new regime, Safford was transferred to OP-20-Q, a code security section.8 Simultaneously joining OP-20-G was Commander Joseph “Buzzard” Wenger, a former Safford acolyte. Tall, skeletal, outwardly humorless, abstemious yet plagued with intestinal ills, Wenger was a 1923 U.S. Naval Academy graduate with seagoing communication experience on board cruisers.9

Wenger faced ever-worsening challenges. Adolf Hitler had unleashed Operation Drumbeat; within weeks his U-boats did more damage to American-flagged ships than had the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. And B-dienst, Germany’s OP-20-G counterpart, had added a fourth replaceable rotor to the Kriegsmarine Enigma. The British called this new configuration “Shark.”10

Against this backdrop, Wenger scrapped earlier work on Enigma and embarked on OP-20-G’s proprietary bombe project. Wenger organized a new section designated OP-20-M and ordered its head, 39-year-old Lieutenant Commander Howard T. Engstrom, to devise the quickest way to defeat Shark. A New Englander with a Yale doctorate in math and fluency in German, Engstrom had first received a reserve commission in 1936. Working with Safford during active-duty stints, he’d already done some preliminary theoretical work on the Kriegsmarine Enigma.11 Now, Engstrom and a growing cadre of OP-20-M experts believed their only hope against Shark lay in the potential of high-speed calculators using photoelectric sensors.12

Their work began inauspiciously. After having fought aggressively for centralized operations, OP-20-G’s new leaders witnessed how Safford’s decentralized approach and use of more traditional cryptology methods paid off. A small Hawaii-based team, led by Lieutenant Commander Joseph Rochefort, broke through Japanese naval code JN-25 sufficiently to intuit enemy plans for attacking Midway. Rochefort’s imperfect but ingenious code-breaking helped turn the tide in the Pacific—inevitably leaving the impression Navy cryptologists worked only on Japanese projects.

Meanwhile, OP-20-M was forced to backtrack, obtaining technical details Denniston had offered Safford months before.13 Signaling further cooperation, the British agreed to host two OP-20-M Navy officers on a semipermanent basis at Bletchley. GCCS and ONC also signed off on a new formal agreement guaranteeing full information exchange on Shark. GCCS was by now undergoing its own upheaval. Alistair Denniston and Alan Turing were shunted aside, Denniston in favor of a “table-thumping” manager capable of industrializing Bletchley’s efforts, and Turing to pursue purely technical work before embarking on a visit to America at the end of 1942.14

In early September 1942, as OP-20-M’s math and engineer wizards fine-tuned specs, Wenger and Engstrom received carte blanche to manufacture American bombes—perhaps hundreds. For design and manufacture they enlisted the National Cash Register Company (NCR) of Dayton, Ohio, and its 35-year-old electrical research head, Joseph R. Desch. A Dayton-born son of a German wagon-maker, Desch had been raised near the location where Orville and Wilbur Wright had built their first airplane. He had worked his way through college to earn an electrical engineering degree and had been employed by Dayton Electric and Frigidaire before joining the “Cash.” Because of his heritage and his top-secret war work, Joe Desch would be entirely cut off from his German-American relatives.

In November the Navy began building the U.S. Naval Computing Machine Laboratory (NCML) on NCR’s grounds. Within weeks came news that Bletchley Park had actually broken the four-rotor Enigma using three-rotor bombes. Fifty such bombes were already in the production pipeline, and the British fully expected to have a four-rotor bombe operational in early 1943.15 Despite the prospect that its extravagant project might be superseded, the Navy proceeded.

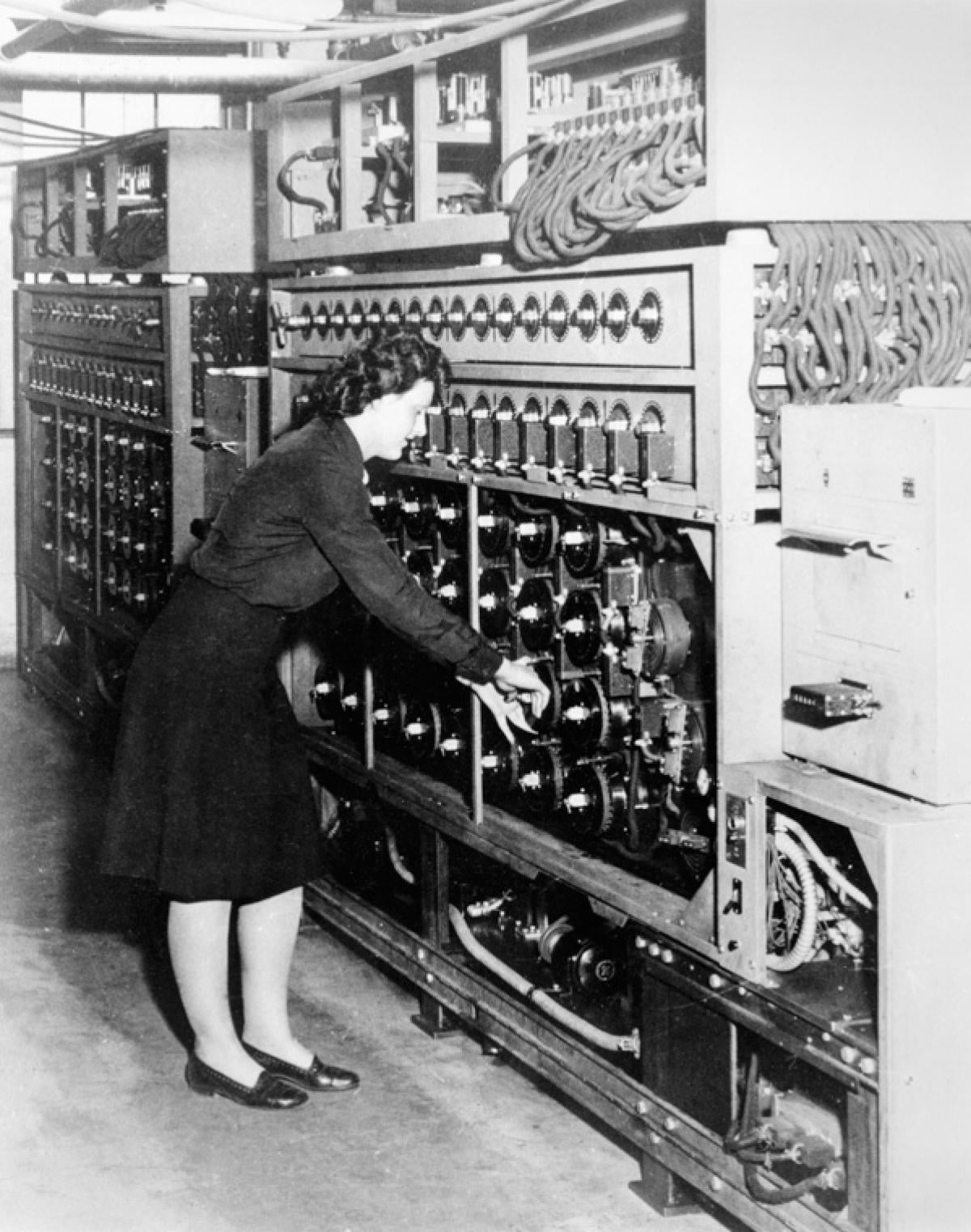

NCML moved into Building 26, a former NCR night school adjacent to a railroad spur. Simultaneously, in Washington, the Navy commandeered Mount Vernon Seminary, a 15-acre former girls’ school in Northwest Washington, and began building a two-story structure to house the bombes, plus living quarters to accommodate the WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Services) to operate them—like their Bletchley Park counterparts, the WRENS (Women’s Royal Navy Service.)

Progress as the Battle Turns

Turing’s top-secret December 1942 visit (there may have been more than one) to Dayton combined advice and eavesdropping. There was really not much new for GCCS to share, leaving Desch to conclude that Turing had come to second-guess and delay his work. Indeed, Turing’s recommendations necessitated changes to a second bombe prototype, even as Desch and his staff scrambled to produce the first. In the end, though, it became clear that Engstrom and Desch’s concept, especially the use of digital and electronic tracking, was groundbreaking.

In May 1943, the first two bombe prototypes—dubbed “Adam” and “Eve” and small enough to be mounted on sawhorses—emerged. One cryptology scholar described Adam and Eve as “wheezy,” prone to oil leaks and short-circuiting, and capable of running for just minutes, not hours.16 But Engstrom, in his own project history, described the pair as “immediately successful.”17 Adam and Eve—and subsequent prototypes “Cain” and “Abel”—were used to run decryption trials on a backlog of Enigma messages. Eventually came word from Washington that a 22 June decryption of a 31 May Shark message had been “worth the entire cost of the project.”18

By now, even without NCML’s bombes, the Battle of the Atlantic was turning in the Allies favor—both on shore and at sea. In March 1943, an OP-20-G analyst had determined that the Germans were reading British naval Cypher 3—a convoy dispatch cipher used by the Allies. The shift to Cypher 5 produced a dramatic drop in merchant sinkings. U-boats sank 41 merchant vessels in May, but thereafter their monthly total never exceeded 14.

The seagoing turnaround was equally stunning. From May through August, the Allies sank 106 U-boats, 21 more than in all of 1942.19 Success here came from many directions. In May, for example, the U.S. Navy created the 10th Fleet, a central command (with no ships) that deftly orchestrated hitherto fragmented resources, strategies, and tactics. The introduction of U.S. Navy escort carriers as well as increased use of very long-range (VLR) bombers, particularly antisubmarine-warfare-equipped B-24 Liberators, improved convoy air coverage and also allowed proactive sub hunting. Not least were advances in weaponry and technology. Escort vessels carried new forward-projecting Hedgehog mortars and small high-frequency direction finders (HF/DF, or “Huff Duff”). And aircraft were equipped with small “Fido” homing torpedoes and compact airborne surface vessel (ASV) radar.20

U.S. Bombes Enter the Fight

As NCML’s production phase neared, 70 WAVES arrived in Dayton. They were mostly in their twenties, fresh out of boot camp, sworn to utmost secrecy, and ordered to travel “out west” by train with no idea of their ultimate destination. These women, and hundreds more to follow, were housed at Sugar Camp, a rustic 31-acre reserve built as an NCR sales-force retreat.21

The WAVES wired, soldered, and assembled parts for the bombes, each task performed in a separate, locked room that gave no hint of the final product. Even their assigned rate, specialist q, was cloaked in mystery. Shifts were long and unrelenting—8 to 12 hours around the clock. If asked by outsiders what they were doing, the WAVES were instructed to say they were being trained on adding machines.22

The first Bombe Model 530 was finished on 4 July 1943. It cost $45,000, stood eight by seven by two feet, weighed 5,000 pounds and contained 1,500 vacuum tubes and 11,000 wheels, each spinning at 2,000 rpm.

Operational problems persisted, but, as bombe assembly proceeded at a rate of four per week, enhancements in machine storage, handling, and refurbishment resolved them. By 1 September, a year after the project’s inception, the first four 530s had been crated, put under armed guard, loaded on a train at the Building 26 spur, and shipped to Washington. As the machines were being installed, maintenance and operational personnel from Dayton—assigned to a unit designated OP-20-G4E—relocated to what was now called the Naval Communications Annex. In the next months, annex bombe operations steadily ramped up; by 1 January 1944, fully 84 were online.

The 530s generated tremendous heat and noise. Operators sweltered, many developed ear problems, and a few even had to dodge flying parts. Machine setup was painstaking and physically demanding. But, given a crib, the 530 could “try” 20,000 letter combinations per second, fully testing a four-rotor Enigma crib in 20 minutes.23 Six times faster than the British three-rotor bombe, the 530 also proved more reliable and three times faster than the Brits’ four-rotor bombes.24

Solutions suggested by bombe “tries” were now run on “print tester” machines in hopes of finding a “jackpot”—what operators believed to be a decrypted key for the day. If intercepted transmissions could be pegged to a solved daily key, message decryption was relatively straightforward. Setting an Enigma analog machine—called an M-8—to the known keys produced a fully decrypted message. By the summer of 1944, with 120 American bombes up and running, the Allies were solving Shark keys within half a day. Many Enigma messages were being read at virtually the same time they were received by German clerks. Not surprisingly, major responsibility for Shark deciphering gravitated to OP-20-G, freeing up Bletchley Park for even higher-level cryptology tasks. Eventually, the Naval Annex created excess capacity, enabling “time-sharing” for British needs in decrypting German army and navy transmissions.25

The Cryptologic War Continues

But the Enigma battle was hardly over. The Allies always feared Germany might catch on to Enigma’s vulnerability, though they never did. (Time after time, the Germans attributed Allied success to coincidence or improvements in radar or other technologies.) Still, there were frequent Enigma upgrades to anticipate. The four-wheel Enigma might become the standard for all German military traffic, for example, or the fixed “reflector” rotor might become “pluggable.”26

There were even older puzzles to crack. Since 1939, for example, Japanese naval attachés’ use of a cipher machine dubbed “Coral” (Pacific devices were named after deadly snakes), and a code system called JNA-20 had defied OP-2O-G. Now its scientists developed a bombe-like machine called “Rattler” that proved instrumental in retrieving priceless information. Berlin’s Japanese naval attaché, awed by Nazi science, obligingly leaked information on new radar detectors, pattern-running torpedoes, and snorkel-equipped U-boats. His most consequential leak became one of Ultra’s greatest coups: detailed data on Germany’s Atlantic Wall fortifications.27

D-Day, 6 June 1944, opened the floodgates for both Bletchley and the Naval Annex. When the Germans lost telephonic lines between Berlin and Atlantic Coast U-boat bases, radio transmissions yielded a bounty of cribs.28 Through much of the summer, the sheer volume of decodable intercepts overwhelmed staff. But as those demands eased, Shark mastery was newly threatened, this time because German seagoing wolf packs were being dissolved. Lone-wolf U-boats generated fewer messages and fewer cribs, upping bombe solution time.

Then, beginning in October, came new B-dienst innovations. One was a device to routinely change Enigma plug-board connections with the simple turn of a knob, effectively halving bombe power. Another was Sonder, a limited submarine network system involving more frequent changes in both plug-board and rotor settings.

Only the German failure to entirely replace Enigma seemed to keep the Allies ahead in the vital game of secrets. As it was, from January through April 1945, U-boat predations increased merchant losses—though never to levels experienced in 1943. It required concentrated U.S. bombing attacks on remaining U-boat pens to finally end the menace.

Meanwhile, human stresses took a different toll. In September 1943, as the first Bombe Model 530s were being crated and shipped to Washington, an ailing and overwhelmed Joseph Wenger retreated to a Florida cabin for six months of isolation, recuperative walks, kite-flying, and sketching. Then, in December 1944, much restored, he traveled to Dayton to coax Joe Desch back to Building 26 from a six-week self-imposed exile clearing brush and chopping wood.

Closing the Top-Secret File

After war’s end, seized documents and interrogations of B-dienst personnel revealed just how fragile Allied advantage over Enigma had been. The Germans had produced prototypes for a 15-rotor Enigma.29 By V-J day, meanwhile, most of the Navy’s bombes were being dismantled for destruction or burial at sea. Adam, Eve, Cain, and Abel were purportedly dumped into a former canal bed on land now occupied by an Ohio county fairground.

Joseph Wenger continued as OP-20-G head until it was folded into a new unified Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA), the predecessor of the National Security Agency (NSA). Promoted to rear admiral, he served as a deputy AFSA director for Communication Intelligence (COMINT) and in 1952 became vice director of the NSA. After his 1958 Navy retirement, Wenger continued to serve as a member of NSA’s Scientific Advisory Board until his death in 1970.30

Howard Engstrom, no longer a Navy officer, hatched plans for Engineering Associates (ERA), an independent technology company, to produce military COMINT equipment. In 1946 the Navy awarded ERA contracts that would assure its survival and make it one of the postwar’s first suppliers of large-scale electronic computers.31 Of the 55 people in ERA’s first technical group, 40 came from OP-20-G and 5 from NCML.32 (ERA was eventually absorbed into Sperry-Rand.) Like Wenger, Engstrom became an NSA deputy director and later served on the agency’s Scientific Advisory Board.33

For his part, Joe Desch was worn out. He declined offers to be further involved with OP-20-G, AFSA, NSA, or ERA. He instead stayed with NCR in Dayton, working in his own private laboratory for the next 25 years. Eventually, NCR turned down his request to launch a subsidiary devoted to electronic machines and computers. It was not until well after Desch’s 1987 death that his family learned he’d been secretly awarded the National Medal of Merit—America’s highest civilian award for wartime service. (Other NCML personnel received certificates of commendation from the Bureau of Ships.)

Remarkably, it was the British government that first lifted the veil of secrecy, revealing in 1968 the basic story of breaking enciphered German messages during World War II. In the spring of 1974, it permitted the first references to Ultra. This was followed by F. W. Winterbotham’s book The Ultra Secret. Only in 1995, at a reunion organized for WAVES and sailors who worked at NCML, was it possible for them to discuss with colleagues and family some of what they had done during World War II. Today, a single, silent Bombe Model 530 on display at the NSA’s National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade, Maryland, is the last tangible monument to Wenger, Engstrom, and Desch’s remarkable wartime endeavor.

1. Clay Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunters, 1939–1942, (vol. 1) (Modern Library War) Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Kindle locations 3153-3193.

2. John A. N. Lee, Colin Burke, and Deborah Anderson, “The US Bombes, NCR, Joseph Desch, and 600 WAVES: The First Reunion of the US Naval Computing Machine Laboratory,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, July–September 2000, 2.

3. Jim DeBrosse and Colin Burke, The Secret in Building 26: The Untold Story of America’s Ultra War Against the U-Boat Enigma Codes (New York: Random House, 2004), xxii–xxiii.

4. Lee, Burke, and Anderson, “The US Bombes,” 3I. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 1, Kindle locations 3227–3234.

5. Ibid. Kindle Locations 3880–3881. Other sources pegged it to the name of an ice cream confection enjoyed by the Polish cryptographers.

6. Ibid. Kindle Locations 3248–3260.

7. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 25.

8. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 1, Kindle locations 12403–12413

9. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 56–58.

10. Ibid., 66–67.

11. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 1, Kindle location 6059.

12. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 60–61.

13. Ibid., 68.

14. Clay Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunted, 1942–1945 (vol. 2) (New York: Random House, 1998) 13–16.

15. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 99, 89.

16. Ibid., 101–4.

17. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 2, 324–25

18. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 110, 119.

19. Ibid., 112.

20. Ibid., 115–17.

21. Ibid., 127–32.

22. Ibid., 134–36.

23. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 2, 325, 414–15.

24. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 103, 175.

25. Ibid., 139–40, 166, 168, 172.

26. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 2, 544.

27. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 175-77.

28. Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 2, 545.

29. DeBrosse and Burke, The Secret in Building 26, 193.

30. Hall of Honor 2005 Inductee Rear Admiral Joseph N. Wenger, USN, NSA/CSS, www.nsa.gov/about/cryptologic_heritage/hall_of_honor/2005/wenger.shtml.

31. Emerson W. Pugh, Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 27.

32. Committee on the Future of Supercomputing, Computer Science and Telecommunications Board, Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences, National Research Council, Getting Up to Speed: The Future of Supercomputing. National Academies Press, 3 February 2005, 29.

33. Arthur Norberg, Lawrence Computers and Commerce: A Study of Technology and Management at Eckert-Mauchly Computer Company, Engineering Research Associates, and Remington-Rand, 1946–1957 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995) 106–7.