From battling the Spanish at Manila Bay to bringing home the remains of the Great War’s American Unknown Soldier, officers and enlisted men of the USS Olympia (C-6) served heroically and honorably at sea. But a group of the famous protected cruiser’s sailors further contributed to Olympia lore in a distinctly different way. These bluejackets fought on land, in North Russia, in the undeclared Allied war against Bolshevik, or “Red,” forces. In the process, the Olympia sailors became the first U.S. servicemen to battle communist troops.

The roots of the Allies’ intervention in the Russian Civil War date back to Czar Nicholas II’s abdication in March 1917 and the formation of a provisional government that pledged to keep Russia in the world war. Economic and military aid to the country from the Western Allies continued to arrive in ports such as Murmansk and Archangel, but after a Russian summer offensive turned disastrous, mutinies and desertions swept through its army, which virtually melted away. The Bolsheviks came to power in the autumn, and the new regime’s first order of business was to withdraw the country from the war.

Led by France and Britain, the Allies decided to intervene militarily in the subsequent Russian Civil War to protect stockpiles of matériel in Murmansk and Archangel. The Western powers also hoped to rescue the 70,000-man Czech Legion, which was stranded along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Former Austro-Hungarian draftees, the legionnaires had switched sides and fought alongside czarist troops. Allied leaders further hoped that their forces could link with anti-Bolshevik “White” Russian troops, help overthrow the current regime, and reopen the Eastern Front.

In early 1918, with the war in France his biggest concern, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was reluctant to send troops anywhere other than to the Western Front. But he eventually agreed to commit one U.S. Army regiment, the 339th Infantry, to a North Russia expedition and send as an advance party the cruiser Olympia, which arrived at Murmansk on 24 May. With the remote port rumored to be in danger of capture by German and Finnish troops, local Soviet authorities welcomed the Americans and other Allies. Thousands of miles away, Allied forces also would occupy Vladivostok, the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

Quickly into Action

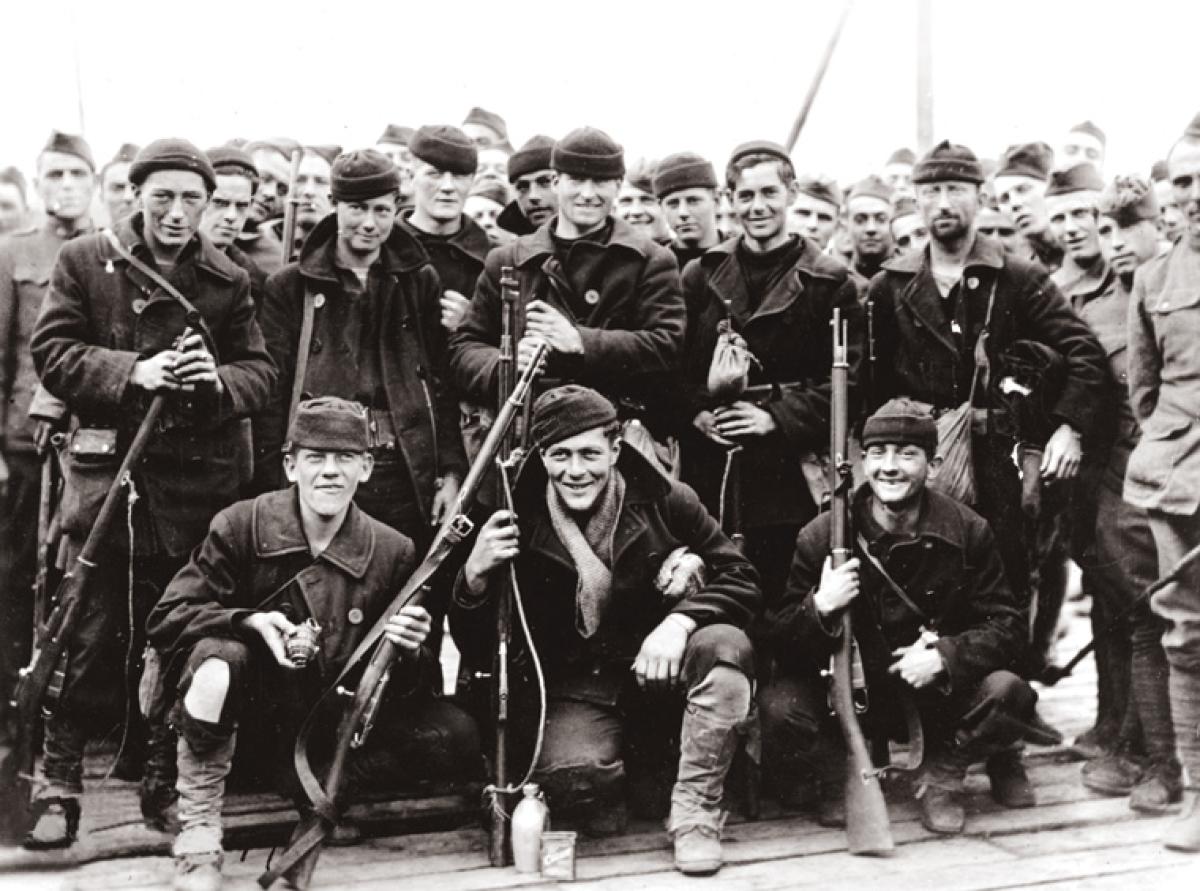

In late July, Olympia Captain Bion B. Bierer ordered Lieutenant Henry Floyd to select 50 men who would form the U.S. contingent for the capture of Archangel. Lieutenant Floyd and his men were delighted by the prospect of seeing some action. Since the cruiser’s arrival in Murmansk their life had mainly consisted of drill, punctuated by shore duty in the ramshackle town.

Floyd picked his men, members of the 1st Company, and they boarded the SS Stephens, part of the operation’s international armada. While the Olympia would remain at Murmansk, the small contingent of her sailors would be the first Americans to land as part of the Allied Expeditionary Force, the 1,300-man North Russia invasion contingent.1 There was little resistance to the 2 August landings, only from some Bolsheviks—commonly called “Bolos”—who fled to the south when they saw the armada.

Captain Bierer, who accompanied the expedition’s commander, British General Frederick C. Poole, on board his yacht, reported of the U.S. sailors’ arrival: “Two officers and 25 men landed with the landing force and 25 men at Archangel. They were divided due to the desires of Admiral Kemp [the British invasion fleet commander], who felt the great desirability of having American forces here.” Bierer went on to say that the admiral “also wanted the Olympia’s band ashore to be used in recruiting Russians.” Its 22 members would arrive on 7 August.2

Assigned to railroad-yard duty, Olympia Ensign Donald M. Hicks and 25 of the cruiser’s sailors boarded a ferry on 3 August and headed for the yard in Bakaritza, on the far bank of the Northern Dvina River from Archangel. There, Hicks and his intrepid men went searching for adventure. It came in the form of an abandoned old steam locomotive that still had some life. Coupling a few flatcars together behind the engine and fortifying them with sandbags and machine guns, the sailors roared south on the Vologda Railroad, which stretched to Moscow, in search of Bolos.3

They caught up with a band of Reds 30 miles from Archangel and banged away from their cars with the machine guns and their rifles. But the sailors soon found they had met more than their match and abandoned the flatcars for better defensive positions. There they remained for several days, accomplishing little. The brief mention of the episode in the Olympia’s war diary states that on 10 August Hicks and one sailor brought in 54 Bolshevik prisoners from Tundra, 30 miles south of Archangel. Sailors were still there, along with a few French soldiers, on 11 August.4

That same day, Hicks and his railroad adventurers were assigned to Force B under British Lieutenant Colonel Haselden. They were ordered to travel on barges up the Dvina to Siskoe, then debark and move southwest to capture Plesetskaya, on the Vologda Railroad, south of Obozerskaya. The plan was for Force B then to attack Obozerskaya from the south as the Allies’ Force A was attacking from the north. General Poole’s ultimate goal was to push 300 miles farther south to the Trans-Siberian Railroad, where his forces might link with the Czech Legion. It was an ambitious plan that bordered on fantasy.

The Olympia landing party’s other 25 sailors were assigned to a railroad force under Ensign James G. Williamson. They joined a French detachment that was accompanied by an armored train. Virtually no records exist of their service on the “railroad front”; however, one of the U.S. sailors, Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Emil A. Keranen, earned the Navy Cross during that time. According to his citation, “He commanded a gun section and did good work under extremely trying weather conditions in advanced positions before defenses were made.”5 The only other specific mention of Ensign Williamson’s command is a 22 August entry in the Olympia’s log that his railroad party brought 14 Bolo prisoners into Archangel.6 Fortunately, Ensign Hicks filed a detailed report of events involving his sailors-turned-infantrymen.

Initial Clash and Olympia Casualty

Force B was a mixed group. Some of its members were French, some Polish; others were Russian, members of the Slavo-British Allied Legion, most them were deserters from the Red Army. There were even a few Australians. But the unit totaled fewer than 200 men.7 As Hicks’ group and the rest of Force B slowly made their way upriver against the Dvina’s swift current on board barges, Red forces were gathering. After a two-day trip, the Allied unit disembarked at Siskoe, 120 miles south of Archangel, and headed west toward Plesetskaya.

During the early days of the intervention, the Allies knew little about this part of Russia; maps and even local knowledge were questionable at best, and advancing a small force into Bolshevik-occupied territory was ill-advised, if not foolhardy. Still, Force B marched 30 miles into the virtual unknown, pausing in several villages on the way. Hicks reported that the people were friendly, and some even cheered for the Allied force.8

When the force arrived at Tiagra at 0300 on 15 August, scouts reported that the next town, Seletskoe, was occupied by 250 Bolshevik sailors equipped with an armored car, seven machine guns, and two 18-pounder field pieces. Nevertheless, later that day Force B advanced and at 1700 began its attack. Little was reported about the battle except that the town was taken by 1930 and, except for a few snipers, clear of Bolos by 2230. According to Hicks, “The fight lasted about five hours and they kept us fairly busy.”9

The casualty list offered evidence of that: one British officer and five soldiers (four French, one Polish) were killed, and one officer and five men were wounded. An American, Seaman George D. Perschke, was shot in the arm, becoming the first U.S. casualty of the intervention. He and the other wounded, along with the unit’s surgeon, returned to Archangel.10 (Perschke was admitted to the hospital there on the 16th, and after his discharge on the 22nd remained with the Olympia band in the headquarters city.) Hicks’ 23 September report noted that seven were killed, so there may have been one more fatality.11 The ensign wrote that “The men I have with me did very good work the day of the [Seletskoe] fight. Col. Hasseldon [sic] thinks a great deal of them.”12

After the capture of Seletskoe, Force B returned to Tiagra and rested until 22 August, when the unit, with Hicks and his sailors manning eight machine guns, captured the village of Verst 19 without a struggle. That night Haselden received instructions, dropped from a British plane, to break off the move on Plesetskaya. Force A was planning to attack Obozerskaya from the north at 0600 on 31 August. Force B was ordered to cooperate by simultaneously assaulting the town.

Attack, Retreat, and Rescue Attempt

In accordance with the orders, Force B returned to Tiagra, where it rested and trained for several days. While there, reinforcements arrived from Archangel: 50 anti-Bolshevik Russians and 3 officers, along with a pair of machine guns. The new arrivals were sent to Seletskoe to guard Force B’s southern flank.

The bulk of Force B left Tiagra on 27 August, advancing 19 miles along the Obozerskaya Road on the first day and another 13 miles on the 28th. Haselden sent an advance party to test enemy strength but was concerned to learn of trouble to his rear: A large party of Bolshevik sailors was headed for Seletskoe. The lieutenant colonel sent one of Hicks’ men, Seaman Corbin P. Hardaway, on horseback to Force B’s headquarters at Tiagra with news of the Soviet advance.13 Hardaway was awarded the Navy Cross for his efforts, his citation crediting him with “accomplishing a long march successfully under trying conditions, and at times practically within the enemy’s lines.”14

Meanwhile, as Force B neared Obozerskaya, it began clashing with Bolsheviks. The fighting became heavier, but the unit arrived on schedule. According to Hicks’ report, “In obedience to orders attacked town at 6:00 A.M. August 31st but could not advance due to heavy resistance met.”15 There was no communication between Force A, attacking from the north, and Force B, even though some of Haselden’s men reported hearing firing from that direction. Olympia Seaman Charlie B. Ringgenberg was wounded, a Bolshevik bullet shattering the bone in his left arm.

The battle lasted through the day, and that night the Americans, under Ensign Hicks, took charge of the front line from the French. The cruiser’s contingent suffered its third casualty when Seamen Bert W. Gerrish sprained his left leg while taking cover from enemy fire.

Early on 1 September, the sailors located six Bolshevik machine guns but knew there were many others. Fortunately, the enemy’s fire was high and ineffective. When ten Bolos suddenly appeared out of the woods about 20 yards ahead, Allied machine-gun fire cut them down. At 0800 Hicks was relieved on the front line. Several hours later distressing news arrived: The Red sailors had retaken Seletskoe and Tiagra and were marching toward Obozerskaya. Reportedly, the Russian force Haselden had sent from Tiagra to Seletskoe to protect the southern flank “fired three shots at the sailors and then sought salvation in flight.”16

The situation for Force B now was critical. Its losses had been minimal, considering the fighting in which it had been engaged, but the Reds before them and approaching from their rear heavily outnumbered the Allied unit. With ammunition running low and no news from Force A, at 2200 Force B retreated 13 miles back along the Obozerskaya Road and set up its defenses.17

Allied command could offer no immediate help. However, it did reroute three ships carrying the 339th Infantry Regiment from their Murmansk destination to Archangel, informing them that American, British, French, and Russian forces were in peril.18 The 339th landed on 5 September, and its Third Battalion immediately boarded trains in Bakaritza for Obozerskaya, which a French company had captured on the 4th. By that time, there had been almost no communication from Force B since the end of August, and Allied headquarters feared the worst. On the afternoon of 7 September, Captain Mike Donoghue and two platoons of K Company, 339th Infantry set out from the town to find the missing unit.

The platoons covered only 5 miles the first day, camping during a heavy rain. After marching 18 miles on the second day, the soldiers began finding disquieting signs—abandoned equipment, fresh graves, and personal belongings, including a diary kept by Ensign Hicks, whose last entry was for 30 August.19 The situation further deteriorated when the K Company units became lost in the unfamiliar and hostile land. They would remain so for several days before the rescuers were rescued. The two platoons were then ordered to reinforce other 339th units heavily engaged with Reds at Seletskoe.

Escape to the Railroad

What had become of Force B? On 2 September, it was still entrenched on the Obozerskaya Road. That day Haselden, with the Olympia sailors, two Lewis machine-gun teams, and 25 French troops advanced two-thirds of a mile from Force B’s main trenches. The lieutenant colonel ordered the French soldiers to man a front-line trench until 1700, when Hicks and his men, with orders to hold until 2200, would relieve them. The rest of Force B, except for a reserve force on the Obozerskaya Road, meanwhile departed with Haselden’s aide to find a route through swampy woods to the railroad above Obozerskaya.

The French held, but not until 1700 as ordered; at 1430 they fell back on the Olympia contingent’s supporting line. After arriving from Tiagra and Seletskoe, Bolshevik sailors launched a bayonet charge against the French and Americans, whose machine guns beat back the yelling Reds.20 Later, the Bolsheviks launched a second bayonet charge that was likewise repulsed by machine-gun fire, after which they withdrew.21

At 1630 the French set off for the railroad, leaving Hicks and his sailors to defend the front line before following the others through the woods and swamps. Later that evening, the reserve force of Poles and Russians remaining on the Obozerskaya Road was ordered to join Hicks, but instead raided Force B’s abandoned supply wagons.22

The only thing left to do was to destroy everything that could be of use to the Reds. Hicks set explosives among the broken machine guns, supply carts, and equipment. Seaman Harold Gunness recalled that some of the sailors helped Hicks, “turning all the horses loose and destroying supplies. . . . The rest of us stayed on the line until 10:30 p.m. when we also left through the swamps and headed for the railroad.23

With Force B out of touch with other Allied units and its fighters cold and hungry, Haselden ordered his men to find their way as best they could to the railroad. For the next several days, as the soldiers and sailors splashed through swamps and bogs, Allied commanders had no idea of the Force B’s fate. Hicks reported:

At midnight 2nd–3rd the entire party started through the woods and swamps for the railroad, marched till 2:00 a.m., rested till 4:00 then marched till 6:00 a.m. resting one hour for breakfast and one hour for luncheon, no supper; out of rations. Continued march at 6:00 a.m. on the 5th and reached railroad at 3:00 p.m., at a point about 15 verst [10 miles] south of Halmsgorski.24

At the rail line, a party of French soldiers supplied them with rations and revealed that other members of Force B had arrived at about 0800 13 miles to the south. Hicks, who also learned that Allied forces had captured Obozerskaya that morning, was ordered to escort a train loaded with 123 Red prisoners to Isakagorka, turn the POWs over to Ensign Williamson, and then return with his remaining 22 men to Archangel, where they arrived on the 6th.25

Strangely, K Company Captain Donoghue’s rescue orders were issued on 7 September, well after Force B had reached the railroad. A week later, Hicks and his sailors, with the rest of the Olympia’s Archangel contingent, returned to Murmansk and the humdrum of shipboard life. Despite its members’ hardships in the Russian wilderness, Force B losses had been small—only 8 killed and 12 wounded. The Bluejackets suffered two wounded and one injured.

Ensign Hicks joined Seaman Hardaway and Boatswain’s Mate Keranen in receiving the Navy Cross. Hicks was recognized for “distinguished service . . . accompanying the North Russia expeditionary forces, in command of a detachment of seamen operating on shore, where he took a conspicuously courageous part in all the fighting and marching encountered by the force of which he formed a part.”26

When at 0700 on 13 November the Olympia weighed anchor in Murmansk and departed North Russia for good, she left without Hicks. Although the Great War had ended a month earlier, he and a group of Olympia sailors continued to serve in the undeclared war in Russia, as members of the Russian Allied Naval Brigade.27

1. Richard Goldhurst, The Midnight War (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978), 94. Benjamin Franklin Cooling, USS Olympia: Herald of Empire (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 195.

2. Robert Willett, Russian Sideshow: America’s Undeclared War (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2003), 12.

3. E. M. Halliday, The Ignorant Armies (New York: Bantam Books, 1969), 35.

4. Although accounts of this incident appear in a number of American Expeditionary Forces, North Russia reports, the Olympia’s log makes no reference to Hicks’ adventure.

5. Hall of Valor, Navy Cross, Emil A. Keranen, http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=9654.

6. USS Olympia log, 22 August 1918, Record Group 45, entry 254, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA), College Park, MD.

7. Willett, Russian Sideshow, 13.

8. War Diary, USS Olympia, 7 September 1918, Report of Lieutenant Henty F. Floyd, Record Group 45, Box 708, Folder 1, NARA.

9. War Diary, USS Olympia, 23 September 1918, Report of Ensign Hicks, Record Group 45, Box 708, Folder 1, NARA.

10. War Diary, USS Olympia, 22 August 1918, NARA.

11. War Diary, USS Olympia, 23 September 1918.

12. War Diary, USS Olympia, 22 August 1918.

13. Ibid.

14. Hall of Valor, Navy Cross, Corbin P. Hardaway Jr., http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=9513.

15. War Diary, USS Olympia, 7 September 1918.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Halliday, The Ignorant Armies, 40.

19. Halliday, The Ignorant Armies, 78.

20. Willett, Russian Sideshow, 15.

21. War Diary, USS Olympia 7 September 1918.

22. Willett, Russian Sideshow, 15.

23. Ibid.

24. War Diary, USS Olympia, 7 September 1918.

25. Ibid.

26. Hall of Valor, Navy Cross, Donald M. Hicks, http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=9548.

27. Cooling, USS Olympia, 198.