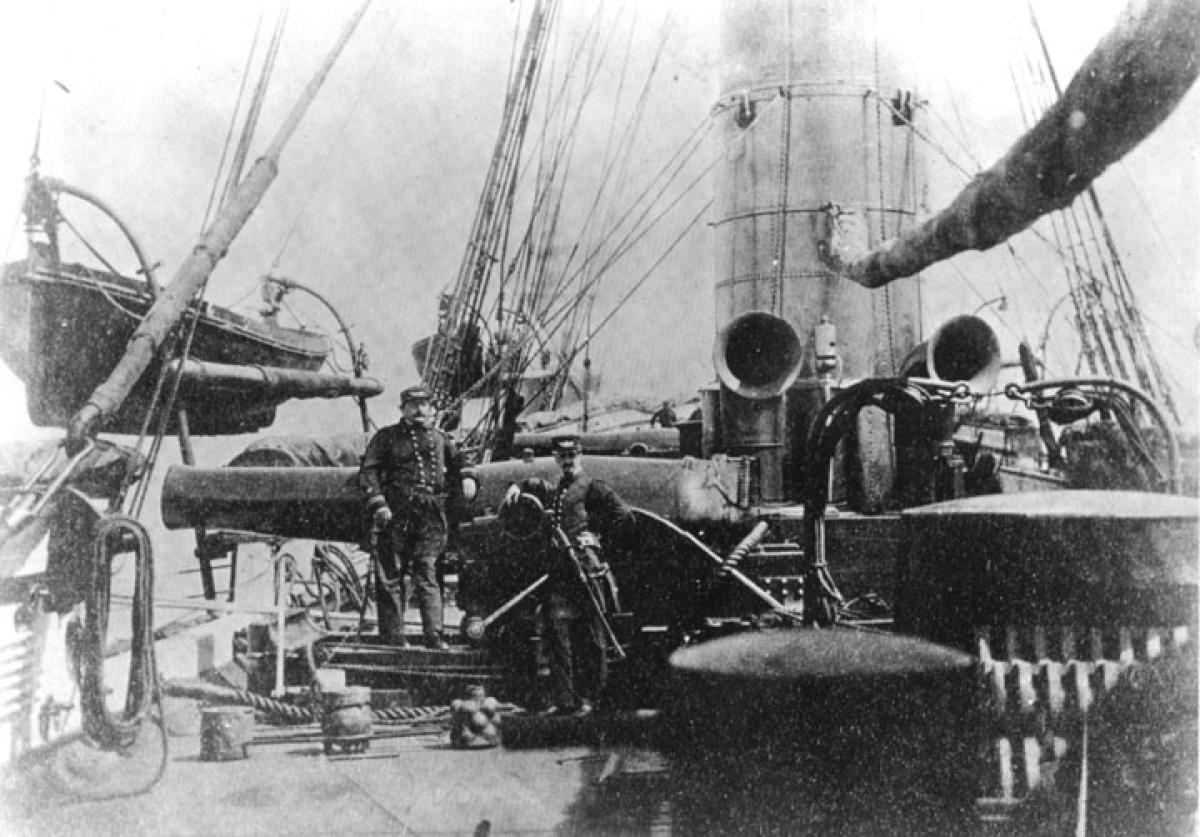

At 0400 on 17 June 1863, the powerful Confederate ironclad Atlanta steamed from the Wilmington River into Georgia’s Wassaw Sound to attack ships of the Union South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Barring her way were two U.S. Navy Passaic-class monitors, the Weehawken and Nahant, each armed with one XV-inch and one XI-inch Dahlgren shell gun and under the overall command of Captain John Rodgers Jr. The casemated Atlanta, captained by Commander John Webb, mounted four Brooke rifled guns: two 6.4-inchers in broadsides and two 7-inchers in pivot mounts capable of firing to either side. She also had a bow-mounted percussion spar torpedo.

Webb made straight for the leading monitor, the Weehawken, intending to use his ship’s torpedo. Unfortunately for the Confederates, in so doing the Atlanta veered from the channel and grounded. She then opened fire, getting off six shots, all of which missed the Union ships. On board the approaching Weehawken, Rodgers withheld fire until the monitor was only about 300 yards distant, at which point her XV-inch Dahlgren unleashed a 400-pound projectile that obliquely struck the Atlanta’s casemate.

While it failed to penetrate, the shot crushed the 4-inch iron plate and its 18-inch-thick oak and pine backing. According to Webb, inside the casemate the impact caused “the solid shot in the racks and everything movable in the vicinity to be hurled across the deck with such force as to knock down, wound, and disable the entire gun’s crew of the port broadside gun . . . and also half of the crew at [the] bow gun, some thirty men being injured more or less.”

In all, the Weehawken’s XV- and XI-inch guns fired just five shots in 15 minutes at relatively close range, four of them striking the Atlanta. Besides the initial shot, a second struck the ironclad’s knuckle, near her waterline, causing minimal damage; the third shot tore off the top of her pilot house, wounding two pilots; and the fourth struck one of the Atlanta’s armored broadside port shutters, breaking it in two and wounding half of the nearby gun’s crew. “Seeing the effect of the Weehawken’s shot,” Webb reported, “and the position she and the monitor Nahant had assumed on each quarter of the Atlanta . . . to save life I was induced to surrender.” The Union monitor’s mighty guns had ended the Confederate threat to Wassaw Sound.

The XV-inch Dahlgren was the most powerful Union naval gun of the Civil War. More widely used, however, were the standard IX-inch broadside and pivot-mounted XI-inch Dahlgrens. These weapons established John Dahlgren as the preeminent American naval ordnance designer of his day.

In 1844 Dahlgren, then a lieutenant, was assigned to direct ordnance activities at the Washington Navy Yard. As well as designing a new lock for firing guns, an improved primer, and new sights, he established ranging data on 32-pounder and 8-inch guns for the first time. In 1849 the innovative officer produced a new family of howitzers. Widely regarded as the world’s finest boat guns of their time, the weapons remained in service with the U.S. Navy until the 1880s. Dahlgren also designed rifled guns, but these were not successful, and most were withdrawn from service in 1862.

Having assumed command of the navy yard at the beginning of the Civil War, Dahlgren was appointed chief of the Bureau of Ordnance in July 1862. Promotions to captain and then rear admiral followed. Soon after the Weehawken’s capture of the Atlanta, he was appointed commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, a position he held through the end of the war.

Dahlgren is chiefly remembered for the system of heavy smooth-bore muzzle-loading guns that bear his name, not for his service at sea. In the decades before the Civil War, the major naval powers were trying to build on the work of French artillery officer Henri-Joseph Paixhans, who had established the efficacy of heavy shell guns for ship armament. The Dahlgren guns were designed to fire explosive shell and designated in Roman numerals to identify them as such.

Wooden ships could withstand a considerable number of solid shot without sinking. Solid round shot left a relatively clean hole that was easy to plug. A shell that was fired at a relatively slow velocity and lodged then exploded in the side of a wooden ship would, however, tear large irregular holes that were difficult to plug and could sink a ship. This had been conclusively demonstrated during the Crimean War when, on 13 November 1853, Russian warships firing shell guns devastated an Ottoman squadron at the Battle of Sinope. As it turned out, however, Dahlgren guns were incredibly strong and proved highly effective when firing solid shot with increased charges against ironclad vessels.

In January 1850, Dahlgren had submitted a draft for a 9-inch gun. The first prototype, cast at Fort Pitt Foundry and delivered to the Washington Navy Yard in May 1850, withstood rigorous testing. With their smooth exterior, curved lines, and preponderant weight of metal at the breech (the point of greatest stress), Dahlgren guns resembled in appearance soda-water bottles, and were sometimes known as such.

The guns were cast in a variety of sizes: 32-pounder, 8-, 9-, 10-, 11-, 13-, 15-, and even—after the Civil War—20-inch bores. The IX-inch gun was the most common broadside carriage-mounted gun in the Union Navy, and the XI-incher was the most widely used pivot-mounted gun. The latter’s shell could pierce 4.5 inches of plate iron backed by 20 inches of solid oak. The XV-inch guns, which weighed 43,000 pounds and debuted in 1862, were even more powerful and were mounted in the larger Union monitors.

Early on, the Dahlgren guns could have been even more powerful. The explosion of the large “Peacemaker” wrought-iron gun on board the steam sloop Princeton in February 1844 had led the Navy to issue a regulation imposing sharply reduced allowable powder charges. This regulation was still in effect when the Union Monitor engaged the CSS Virginia in Hampton Roads on 9 March 1862. There is considerable truth to Monitor designer John Ericsson’s claim that had the Monitor’s two XI-inch Dahlgrens been firing full powder charges with the guns aimed at the Virginia’s waterline, the Confederate warship would have been sent to the bottom.

Even when using partial powder charges, the reliable Dahlgren smoothbore guns provided exceptional service during the Civil War and remained standard weapons in the U.S. Navy until the introduction of breech-loading heavy guns in 1885.