The Night 5-inch Fire Broke the Viet Cong

Joseph Todd, Former supply officer

In his April article “The Ubiquitous 5-inch/38,” (pp. 10–11), referring to the 5-inch/54 weapon, Norman Friedman writes: “It then formed the basis for the postwar power-loaded mountings, which were standard on board destroyers, frigates, and carriers starting in the 1950s. . . . The Navy probably would have preferred to keep the reliable 5-inch/38.”

Indeed, the 5-inch/38 weapon was used on new construction as late as 1963. In January 1965, I reported aboard the soon-to-be-commissioned USS Bradley (DE-1041) as assistant supply officer. Bradley (call sign Comet Express) was the second ship of the Garcia class, which was later reclassified as a frigate. The Garcia class had two 5-inch/38s enclosed single mounts—one forward and one aft. As I recall, the gunner’s mates preferred the 5-inch/38s and had little good to say about the 5-inch/54s.

In 1966, one night while patrolling an area in II Corps during her first WestPac deployment, the Bradley got an emergency call from a Marine outpost that said it was under attack and feared it would be overrun. The captain took us to general quarters and up to flank speed. My battle station was on the bridge, as I was junior officer of the deck, so I recall the events of that night clearly. Captain Whaley told the Marines we were at our maximum effective range and could not guarantee the fall of shot, but they insisted we fire. At a range of approximately 17,000 yards and a speed of 32 knots—rolling, pitching, and yawing—we commenced firing and walked continuous and accurate naval gunfire support down the beach at 25-yard increments. That 5-inch fire broke the back of the Viet Cong attack.

After that incident, every Marine outpost in II Corps wanted “Comet Express” to ride shotgun for them.

Memories of Corpus Christi

Allan L. Peterson

I very much enjoyed Norman Delaney’s article “Corpus Christi’s ‘University of the Air’” (June, pp. 36–41). He did, however, leave out what I thought to be an important addition to what happened there. Corpus Christi was also a recruit training facility.

A PBY hangar was set aside for recruit training, and there were (I would guess) 30 companies of 150 recruits and rows and rows of bunks. The only training was marching. I was in company 30, and we all were future aviation cadets from the Midwest. We were sent there until ground schools opened for us. Our uniform was regular Navy undress blues. This was in 1943.

After about 4 weeks of marching and getting shots, we were split up and sent to various auxiliary bases and squadrons. We worked on the lines as plane captains. I was on an SNJ line at Kingsville Field and later assigned to an OS2U Kingfisher squadron (TS-17). When asked if I wanted to go up on one of their flights, I of course said I did. I was told to check out a chute and a .30-caliber machine gun (no ammo), and to make sure I brought my white hat along. I found out why: It was rough going up, while up, and coming down; I may have needed the hat for an upset stomach, but I didn’t.

After about three months at Corpus Christi, we were assigned to various colleges throughout the United States to begin our ground schooling.

Pillaged Pipe from Battle of Santiago Remains a Mystery

Richard A. Sauers

I read with interest Ensign Carlos Rosende’s article on the 1898 Battle of Santiago (“We . . . Must Expect a Disaster,” April, pp.16–24) and would like to share with other readers an artifact from that battle. The Packwood House Museum in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, has a meerschaum pipe that is attributed to Spanish Rear Admiral Pascual Cervera, according to the paper folded underneath this ornate pipe in its custom case. The writing on the paper specifies that the pipe was taken from the admiral’s cabin on the Infanta Maria Teresa. How it got to Lewisburg is a mystery.

The museum was established after the death of its founder, Edith Hedges Kelly Fetherson (1885–1972), who acquired most of the objects that filled her 27-room house. Her husband, John T. Fetherson, died in 1962 and had been an engineer. His jobs included sanitation commissioner for New York City and work with American Cyanamid Corporation during World War I at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where he was in charge of the construction of Nitrates Plant number 2. It’s entirely possible that John acquired the pipe, which is on display in his former office in the Packwood House Museum.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Sauers is the former director of the Packwood House Museum and the author of many books, including Pennsylvania in the Spanish-American War: A Commemorative Look Back.

A Third Cheval-de-Frise Theory

Ronald James Robert Platt III

In the “Naval History News” section of the April issue of Naval History (pp. 12–13), you give two theories to explain the uncovering by Hurricane Sandy of a 28-foot, 6- to 8-inch diameter spear-like object, apparently a cheval-de-frise, in the Delaware River, but you should add a third.

The first theory given is that the object came from the chevaux-de-frise between Fort Mercer, New Jersey, and Fort Mifflin, Pennsylvania. The piece of a cheval found at that barrier was 18 inches in diameter, which can be explained by the greater depth of the water. The second theory was that it was built because the unfishished Washington and Effingham were floated up the tidal Delaware and defenses (chevaux-de-frise) were built in an effort to save them.

The third explanation that you should consider is that, lacking sufficient naval forces, states made defenses along waterways to the larger towns and military resource areas. The arguments for this theory are based on the existence of barriers we know of and other possible targets like those up the Delaware. The population centers include the Trenton-Burlington area, the Phillipsburg-Lehigh Valley area, and the smaller Columbia-Stroudburg area, which is the gateway to the Water Gap. Morristown was a supply collecting point for General George Washington’s army with lines coming from Sussex County and the upper Delaware; at the York Road, Lehigh Valley, and Brodhead Creek. The Durham boats used by Washington in 1776 were iron ore crafts; West Point to Northern New Jersey was a major iron-industry belt.

Up the Delaware was an organizing zone for Washington’s army. While Washington crossed the river, only a few of the 1,800 men made it across the icy mud flats in the tidal zone and ashore in Burlington.

The defensive barriers that I have found information about include those across the Delaware, Hudson, Lake Champlain, Providence River, and Cooper River. Ground advance rendered the Philadelphia, first Hudson, Lake Champlain, and Cooper River barriers indefensible so they surrendered or were abandoned.

Rules of the Game

Richard Paul Smyers

I was surprised and very pleased to see “Pieces of the Past” cover the Jane Naval War Game in the June issue (p. 72). In the 1960s and 1970s I was a regular member of the Chicago Area Naval Wargames Group that fought naval battles with 1:1,200-scale models and the rules created by the late Fletcher Pratt. While I had heard about Fred Jane’s naval wargame rules, I had never before seen a picture of the equipment before.

A naval wargaming group was organized by Jane and conducted many games to compare ships, tactics, and strategy by using his system of rules. Reports on six of these “battles” were published in the British periodical The Engineer in 1901 and another in 1902. But the biggest series of reports appeared in America in the weekly Scientific American Supplement, from issue numbers 1,407 (20 December 1902) to 1,422 (4 April 1903). These described a lengthy naval wargame between Imperial Germany and the United States.

To the best of my knowledge, this account of the “German-American War of 1903” has never been reprinted in any form. This is rather unfortunate, for it reads like a 1902 techno-thriller and gives many interesting insights to the naval tactics and strategy of that day. I believe Fred Jane drew the many battle maps and ship plans that appear in the articles, as well as wrote them.

Although I’ve never been a member of the U.S. Navy, I am a Golden Life member of the Naval Institute, and since 1966 I’ve been writing book reviews for the quarterly magazine Warship International. I enjoy every issue of Naval History that I get, even if it doesn’t have something about naval wargames in it. Keep up the good work!

One Charleston Stack or Two?

C. P. Hall II

Congratulations on a marvelous June issue of Naval History. It is a real page- turner that the reader cannot put down until he has gone from cover to cover. Chuck Steele’s essay about Admiral Sims (“America’s Greatest Great War Flag Officer,” pp. 56–72) was exceptional, an article worthy of the subject matter.

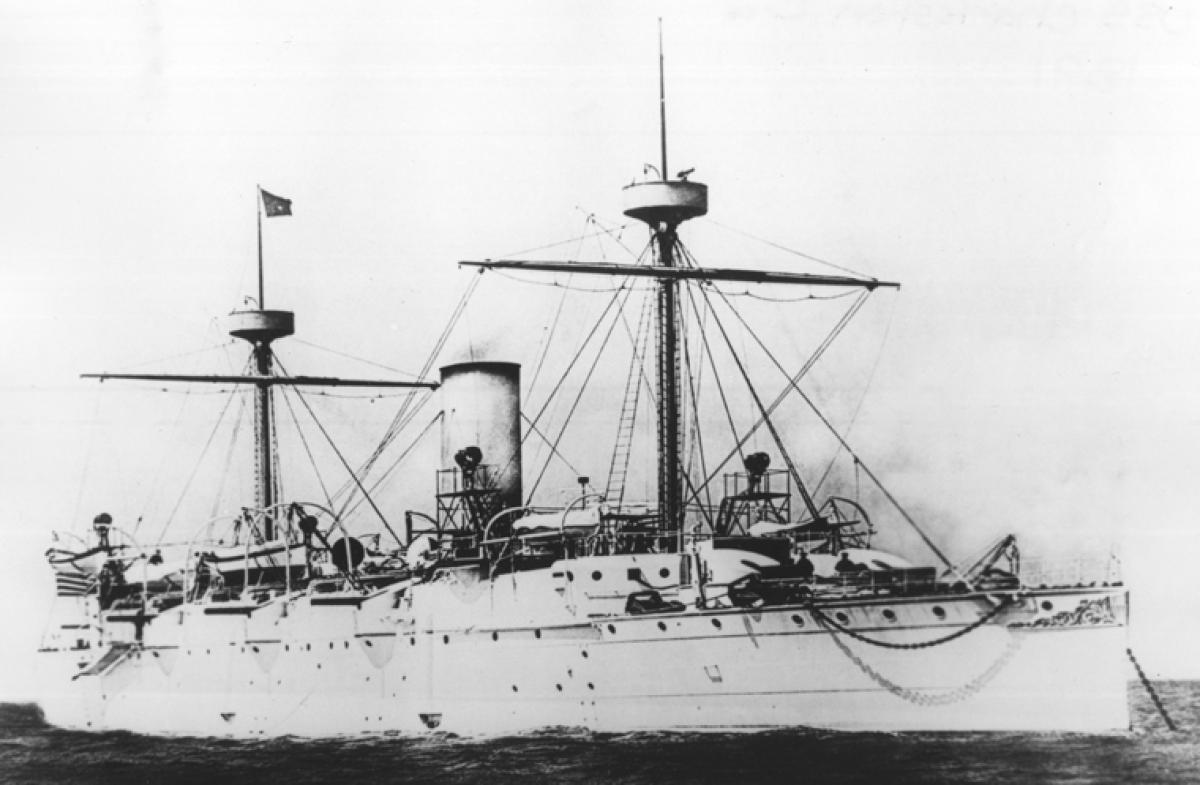

There was one thing that caught my eye, which was the photo on page 60. I do not believe the ship in the photo is the protected cruiser Charleston. I believe the Charleston had only one stack. I would say this is a photo of one of the first class of armored cruisers completed after the Spanish-American War. This would mean it could not have been present at the Sino-Japanese War some ten years earlier. The photo is interesting for other reasons. It appears that the forward main battery turret is missing. There seem to be large letters spelling out something surrounding the bridge.

There is probably an interesting story to be told about this ship and photograph.