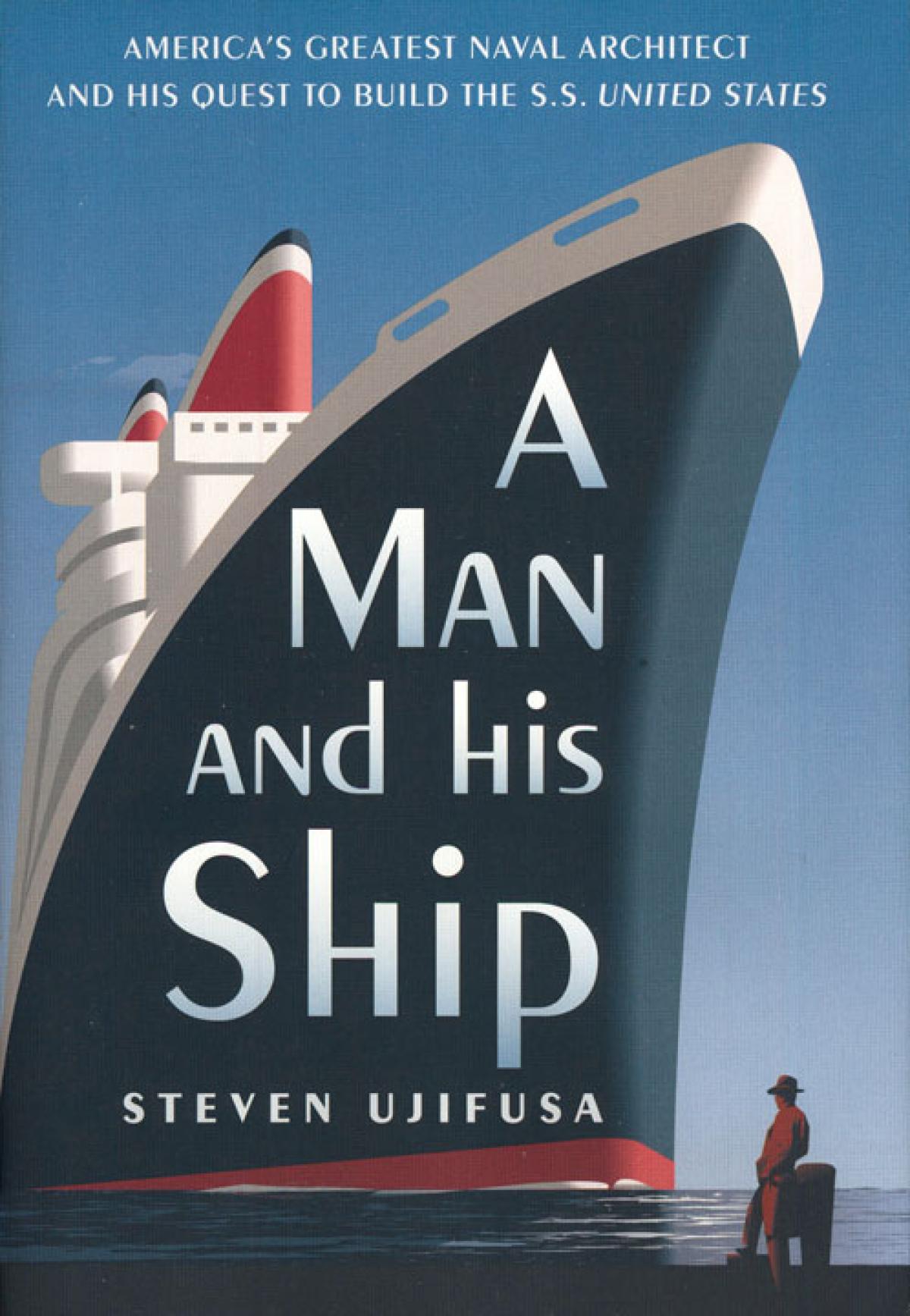

One of the benefits of having a long memory is that various stimuli can evoke pleasant recollections from ages past. I had that experience recently during a browsing visit to the local Barnes & Noble. I saw a book that demanded, “Take me home!” The cover featured a dramatic painting in art deco-ish style. Towering over the composition was the bow of an ocean liner and a bit of her superstructure and funnels. Tucked away in the corner of the painting was the small figure of a fedora-clad man leaning against a bollard. The man was William Francis Gibbs, and he was peering toward his greatest creation, the SS United States.

The title of Steven Ujifusa’s book is most apt, A Man and His Ship, published to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the liner’s spectacular debut in 1952. As I discovered, after I did indeed buy the book and read it, Gibbs and his monument were inseparable. Some 40 years earlier, he had envisioned such a huge oceangoing transport, and he later essentially willed her into being, despite a plethora of obstacles that would have defied someone who wasn’t so obsessed as Gibbs. The book is essentially a dual biography of control-freak Gibbs and his huge assembly of seagoing steel and aluminum.

As I read, the memories from childhood came flooding back. Television had not yet come to Springfield, Missouri, in 1952. (When it did—a single station the following year—the two choices were “on” and “off.”) Instead, I relied on newspapers, magazines, and a medium now long gone—the movie newsreel. Life magazine, a wonderful staple of my youth, contained color pictures of the new ship: a horizontal ribbon of black along the length of the hull, red boot topping below, and the white superstructure above. Most striking were two enormous red, white, and blue smokestacks that glistened in the sun.

The precocious Gibbs and his brother Frederic began planning for a giant, 1,000-foot liner in 1915, when they were not yet 30. The following year they presented their designs to Rear Admiral David Taylor, chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Construction and Repair. They received encouragement, plus some monetary backing from financier J. P. Morgan, but the time was not yet ripe. The United States soon became involved in World War I, and the national need was for troop transports that would be available right away. The war ended before action could be taken on the Gibbses’ plans. Undaunted, they formed their own naval architecture firm in 1922. It later became Gibbs & Cox and exists to this day.

The project that gave the fledgling firm experience and public notice was the reconditioning of the passenger ship Leviathan in the early 1920s. She had been the German liner Vaterland until seized by the United States on its entry into the Great War in 1917. Subsequently during that conflict, she was the U.S. troop transport Leviathan (SP-1326), ferrying thousands of members of the American Expeditionary Force to France and then home again afterward. In the early 1920s, when no German blueprints were forthcoming for the captured ship, the Gibbs team surveyed her and created its own plans. Then it had the ship greatly rebuilt, converted from coal to oil, and refurbished the interior for more spacious accommodations than the soldiers had. She became the pride of the United States Lines.

In the 1930s, the firm designed more passenger ships, as well moving into Navy work with a new generation of destroyers, equipped with high-pressure steam boilers. Author Ujifusa, throughout the book, does an excellent job of explaining the engineering achievements in layman’s terms. The lead ship was the 36-knot Mahan (DD-364), commissioned in 1936 as the first of a new type known as the “Gold-platers,” in comparison with the four-stack destroyers of the World War I generation. As the years passed, the firm continued to grow, working on the designs of a number of World War II vessels, including the ubiquitous Liberty type of cargo ship.

After the war, Gibbs continued to pursue his vision of creating a super liner. The new ship, just short of 1,000 feet, was to be named for the nation, and she became a joint project of the United States Navy and United States Lines. She was to be designed for conversion to troop transport and included national-defense features such as great internal compartmentation and superior speed. To reduce weight and to guard against fire, she was to contain a great deal of aluminum in her structure and furnishings. Newport News Shipbuilding set to work on the new leviathan, which emerged for transatlantic service in 1952. On her maiden voyage the United States set a record for the fastest Atlantic crossing between New York and Bishop Rock off England—an average speed of 35.59 knots. She still holds the record for an ocean liner.

For 17 years thereafter, carrying manifold civilian and military passengers, she was a nautical embodiment of her nation. She was the greatest ocean liner the nation had ever produced, but she carried her workload in a time that was dramatically changing the ways in which passengers moved from one continent to another. Jet planes now offered the fastest travel. In 1969, as the United States lost money in a world that demanded profits, she was retired. In the years that followed, her furnishings were sold off, and multiple proposals for future use, for example as a cruise ship, came to nothing. In recent years, I have seen her sturdy old carcass sitting forlornly on the Philadelphia waterfront. Her glory and her paint have long since faded, but my vivid memories of her youth—and mine—happily remain.