The wooden steam sloop Pawnee pounded toward the South Carolina coast through heavy seas and gale-force winds in the early hours of 12 April 1861. The weather and darkness made it difficult to distinguish landmarks, but the warship’s commanding officer, 52-year-old Commander Stephen C. Rowan, recorded his arrival “as near the position assigned me as the badness of the weather would allow me to judge.” Once in position off Charleston Harbor, Rowan ordered his men to quarters and the guns loaded with shell.

The packet steamer Baltic drew near in the storm, bringing with her “Captain” Gustavus Vasa Fox, who was eager to set his brainchild—the relief of Fort Sumter—into motion. (See story, p. 18.)The Pawnee’s captain, however, when told of Fox’s intent to proceed apace with the mission, said his orders required him to await the arrival of the sidewheel steamer Powhatan. (Unbeknownst to either man, the latter had been ordered elsewhere.)

Then, in reply to Fox’s invitation to stand in toward the bar, Rowan responded firmly that he “was not going in there and inaugurate civil war.”

Commander Rowan, a native of Ireland, was a seasoned seaman, having won appointment as a midshipman in 1826. His ship, however, was a relatively new addition to the Navy. Laid down in October 1858 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, the Pawnee slid down the launching ways on 8 October 1859. Miss Grace Tyler christened the ship with a bottle of claret broken on the figurehead of “a great Pawnee chief.” She was commissioned at her building yard, Commander Henry J. Hartstene in command.

Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey had recommended ten steamers of “light draft, great speed and heavy guns” in his annual report of 1857. Congress authorized eight—seven screw sloops and one sidewheeler—on 12 June 1858. Of the sloops, four were to draw 13 feet, three were to draw 10. John Willis Griffiths received a government appointment to design the largest of the three ships ordered to the latter specification. The 49-year-old son of a New York shipwright and an innovative naval architect in his own right, Griffiths designed a screw steamer of greater length and beam than her near-sisters, which, when fully outfitted, drew less than the 10-foot draft specified. People identified the Pawnee so closely with her designer that some referred to her as “the Griffiths ship.”

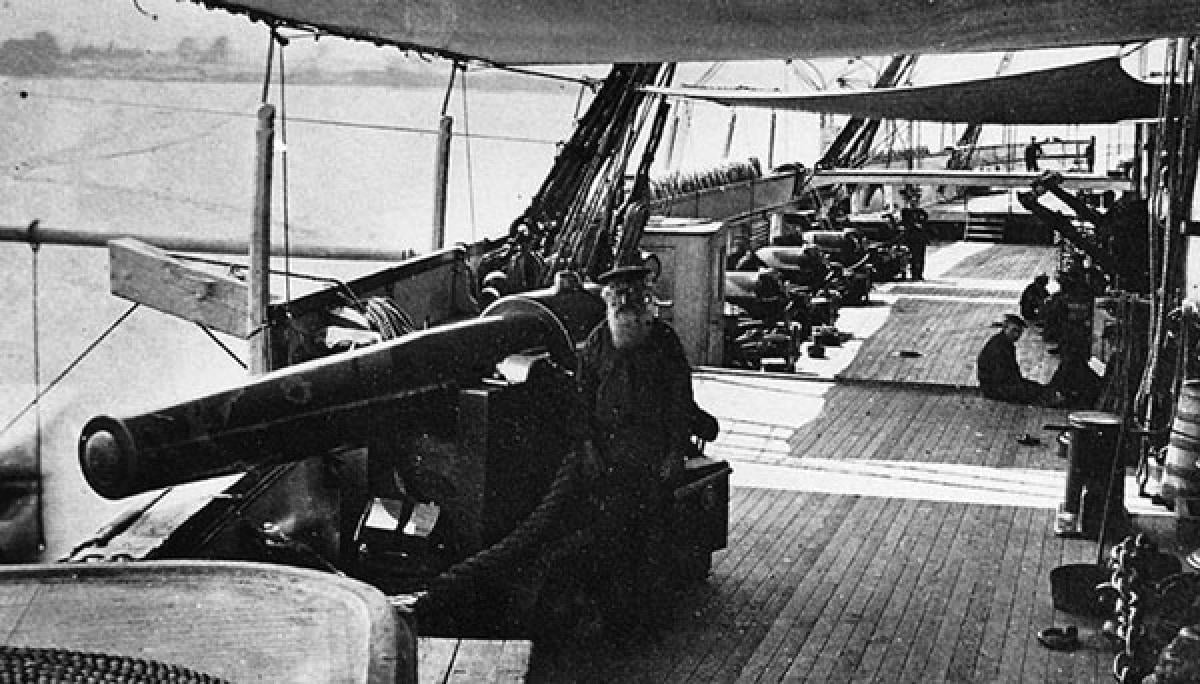

The Pawnee’s main battery consisted of four XI-inch Dahlgren smoothbores and eight IX-inch Dahlgrens. The former were iron guns, each weighing 15,700 pounds that could hurl a 136-pound shell nearly a mile (1,712 yards) with a 15-pound charge, and 1,975 yards with a 20-pound charge. An experienced crew could fire one round every 1.74 minutes for an hour; over a three-hour span the time increased to 2.86 minutes per round. In a real emergency, a good crew could fire a round every 1.33 minutes. The IX-inchers, also of iron, each weighed 9,000 pounds and could hurl a 72.5-pound projectile 1,740 yards, or 75-pound shrapnel 1,690 yards, in both cases using a 10-pound charge.

The Philadelphia firm of Reaney and Neafie, under the supervision of Chief Engineer William W. W. Wood and R. H. Lang, constructed the Pawnee’s engines. A pair of horizontal direct-acting cylinders, measuring 65 inches in diameter by a 36-inch stroke, drove a 7-foot-3-inch master gear wheel, asymmetrically installed just off the centerline to port, which in turn drove two smaller pinions 2 feet, 11 inches in diameter. Unlike the other steamers in the 1858 budget, which had single screws, her propulsion plant drove twin four-bladed screws, each 9 feet in diameter. She could make 10 knots top speed. Given the heavy battery and the weight of the engines needed to drive two screws, Griffiths designed the ship with a concave hull form.

The Pawnee sailed on 14 September 1860 for the Gulf of Mexico, with Flag Officer George J. Pendergrast embarked. Arriving off Vera Cruz, Mexico, on 15 October, she operated with the Home Squadron for less than two months, returning to Philadelphia shortly before Christmas of 1860 to be placed “in ordinary”—a noncommissioned status—soon after her arrival. But she was recommissioned on 31 December, Lieutenant Samuel Marcy in command.

Amid growing tensions between North and South, Rowan relieved Marcy on 18 January 1861. By that time four slave states had seceded from the Union; three more were to follow suit within a fortnight. Although married to a Virginian and fond of the South, Rowan stood firmly loyal to the Union.

The political crisis worsened, and within a few weeks Fox, a former naval officer, commander of merchantmen, and manufacturer, was presenting a plan to Brevet Lieutenant General Winfield Scott in Washington, D.C., for the relief of Fort Sumter. Fox chose the Pawnee for inclusion, reasoning that she was “the only available steam vessel of war north of the Gulf of Mexico . . . [with] heavy guns.” He had also noted that “As a steamer she seems to be a failure, but she may be got ready for this emergency; at least she is, unfortunately our only resource.”

The Pawnee sailed from Washington on the morning of 6 April 1861, reaching Norfolk the next day to take on the supplies made ready for her. After his Bluejackets had stowed them, Rowan planned to sail at daylight on 9 April, but a heavy gale, blowing since the previous Sunday, delayed departure until the following morning.

Now, two days later, he and Fox’s little flotilla were off Charleston. The Baltic, carrying the Sumter-bound supplies, and accompanied by the revenue cutter Harriet Lane, began standing toward the harbor entrance. Rowan ordered his ship’s launch and one of the cutters “readied and armed for the purpose.”

Only then did those in the relief squadron hear cannon fire and realize that the fort was under attack (as it had been for a time) and the war Rowan had not wanted to inaugurate had, in fact, begun. As the Baltic stood out, Captain Fox noted the Pawnee standing in. Rowan hailed Fox, saying that if he could get a pilot, he would take his ship in and share the fate of his Army brethren. As the guns bombarding Sumter thundered in the distance, Fox went on board the Pawnee and convinced Rowan that “the Government did not expect any such gallant sacrifice” of sharing whatever awaited the Army.

Ultimately, the Sumter force that Fox had wanted to resupply ended up being embarked in the Baltic on 15 April. The badly battered fort had been surrendered to Confederate forces and duly occupied. As the flag that had flown over Sumter’s ramparts snapped in the wind from the Baltic’s main truck that afternoon, the Pawnee’s men joined in three hearty cheers for the Stars and Stripes.

But the war was not over for the Pawnee, which went on to see considerable service during the conflict. She retained her eight IX-inch Dahlgrens for the rest of the war. By 5 May 1863 she also mounted a 100-pounder Parrott rifle—capable of firing solid shot and long shells—and a 50-pounder Dahlgren. For a brief period in 1864, she mounted four additional IX-inchers. Soon after hostilities ended, the Pawnee carried one light 12-pounder and a 24-pounder howitzer.

Naval historian K. Jack Bauer praised the Pawnee as “a notable sea boat,” but contended that “her machinery [had been] poorly built.” Eventually, the excessive cost attendant to repairs of her engines prompted their removal in 1869-70. The Pawnee served as a floating store- and hospital-ship until July 1874, then a receiving ship, and ended her days as a store-ship at Port Royal, South Carolina. There, on 3 May 1884, she was sold to M. H. Gregory of Great Neck, New York, for $6,011.