“Our ship was neither a troopship nor a warship,” the renowned war correspondent Ernie Pyle observed, “but it was a mighty important ship. It was not huge; just big enough that you could feel self-respecting and vital about your part in the invasion, yet small enough that it was intimate and you could get to be a part of the ship’s family.”

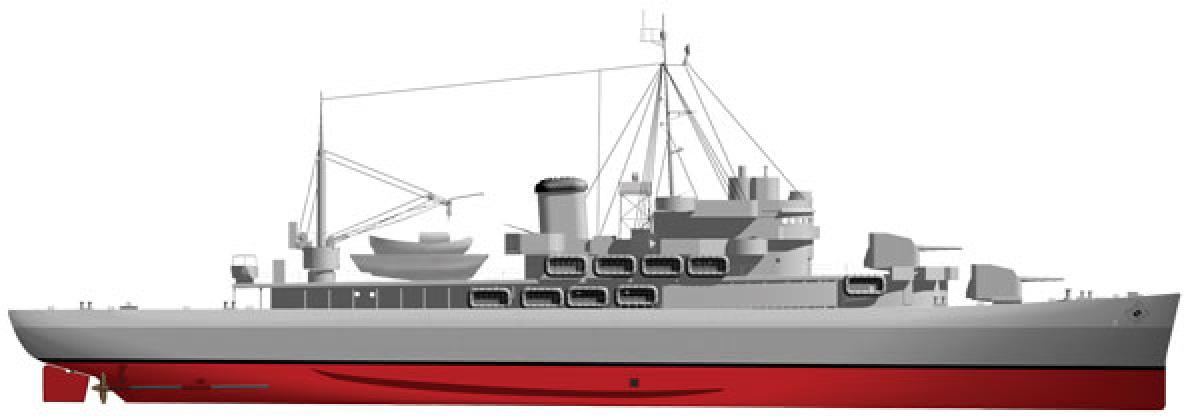

Because of wartime security, when some of Pyle’s dispatches were published in book form—as Brave Men—the ship about which he had written so fondly had to remain anonymous. That “mighty important ship” did, however, have a name—the USS Biscayne (AVP-11). She had begun life as a small seaplane tender, the second of a new class of such vessels whose development had been dictated by the increasingly important role played by patrol planes in naval warfare.

In 1936, in view of contemplated operations in the Pacific, designers of the Biscayne and her Barnegat-class sisters envisioned successive occupations of advanced bases that would require the employment of a small number of light seaplane tenders at each island. Converted minesweepers of the Lapwing class had shown value as adjuncts, for training and for war, but had fallen short of fulfilling all the characteristics needed in such vessels.

Laid down at Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, on 27 October 1939, a little less than two months after war had begun to ravage the European landscape, the Biscayne was launched on 23 May 1941 and commissioned on 3 July 1941, Lieutenant Commander Carleton C. Champion Jr. in command. Proceeding down the West Coast, then through the Panama Canal, the new tender reached Boston Navy Yard on 7 December 1941, earmarked for the Support Force of the Atlantic Fleet.

Plagued by unreliable diesel engines, the Biscayne, like her sister ship the Barnegat (AVP-10), required extensive repairs and alterations before she could enter service. Once the work at Boston fit her out for extended service, she operated off Greenland, Argentina, Sierra Leone, and in French Moroccan waters in the wake of Operation Torch. She performed her designed aviation-tender function into the spring of 1943.

But as plans proceeded for the invasion of Sicily, Operation Husky, changes lay ahead for the Biscayne. Those contemplating the operation decided to employ the vessel—for that evolution only—as a command ship. On 21 April 1943, she transferred torpedoes and bombs with associated warheads, exercise heads, tail vanes, and fuses to the Naval Air Station at Port Lyautey, Morocco, unloading there, as well, her fending-off poles, gasoline hoses, and the charts and publications necessary for an embarked patrol-plane squadron. Flight clothing—including suits, boots, and flying helmets—was removed the next day while the ship began discharging aviation gas and lubricating oil to tanks ashore. Ten desks and five wardrobe-type lockers went to the Advanced Amphibious Training Base at Port Lyautey the next day, when she finished discharging her gas and oil stores.

Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly, who would command one of Husky’s three transport forces, visited the Biscayne for several hours on 28 April, and on the morning of 2 May she shifted her berth to one alongside the repair ship Delta (AR-9) at a pier in Mers-El-Kebir Harbor. A little more than three hours later, the Delta’s repair crew came aboard to begin transforming the Biscayne to a command ship. The artisans built a deckhouse aft, one portion of which served as a code room and the other a war room that was subdivided into three compartments. The latter spaces, containing heat-generating equipment, would prove to be unbearably hot and humid in warm weather.

On the afternoon of 24 May, workers removed three SCR-188 radio sets, and brought on board four 7CSs, one SCR-284, and two receivers, a model BC-603 and a BC-683. During that time, Conolly paid an unofficial visit—most likely to see how things were progressing. Finally, on 31 May, the Biscayne shifted her berth and moored to the breakwater at 0903, where she underwent a quick inclining experiment to make sure the renovations had not added too much topside weight. Conolly broke his flag on board on 6 June. A month later, before she had sailed to take part in her initial operation, her guns spoke for the first time in anger. During an air raid at Bizerte, her 5-inch bursts helped destroy a Junkers JU-88 bomber, and she suffered her first casualties. Two of her crew and one of the embarked Soldiers suffered fragment wounds.

Over the next eight months, the Biscayne, which had been converted only for the invasion of Sicily, led formations of assault craft in three major amphibious operations: Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio. “On each of these [operations] she has proven an excellent navigation and communication ship, her primary mission,” noted Rear Admiral Frank J. Lowry, commander of the Eighth Amphibious Force. Lowry, who flew his flag in the ship during the assault at Anzio, came to “regard this ship with respect and pride for her versatile seamanship, cooperative helpfulness to the small craft, and courageous aggression against the enemy.”

Particularly noteworthy, Lowry observed, was how, as force flagship, the Biscayne “consistently set a high standard of anti-aircraft performance” most often “being the first ship to open fire.” Acknowledging how German fighter-bombers often would approach by imitating Allied tactics, or even by following P-40s or Spitfires, the Biscayne’s gunners would instantaneously recognize the enemy. “The quick-opening, accurate fire of the Biscayne was a controlling factor in defense of the anchorage.” In addition, the ship served as “supply, fuel and water ship for small craft, hospital ship, smoke supply depot, minor repair ship and receiving station.” She had unerringly led assault ships to the correct beach, and in Lowry’s estimation, “could have done so, if necessary, without the aid of reference vessels,” skillfully employing her SC and SG radars.

Acknowledging that “berthing, messing and ship-service overcrowding is difficult for all at times,” Lowry did not feel it to be critical. In fact, “[i]n view of the excellent manner in which the Biscayne gets the job done,” he accepted the “disadvantages of crowding . . . as part of the job.” In sum, “[w]hile the Biscayne is not perfect, [she] is quite satisfactory as an amphibious force flagship.” (Her captain, Commander Edward H. Eckelmeyer Jr., meanwhile, doubted “there are any other ships in the U.S. Navy operating with personnel increased by 200 percent over that for which they were originally designed.”)

“As she stands and on past performance alone,” wrote Rear Admiral Bertram J. Rodgers, who flew his flag in the Biscayne during the invasion of southern France, her fourth major operation as a makeshift flagship, “her record as a flagship has been a good one; she has discharged her function as such in spite of the fact [that] the Flag installations were of a temporary and incomplete nature.” The Biscayne’s men had “performed their duties with ability, courage, and distinction,” and he praised their “pleasant and effective” cooperation.

After receiving further alterations at Boston Navy Yard when she returned from the Mediterranean, the Biscayne was formally redesignated AGC-18 on 10 October 1944 and returned to the Pacific. There she took part in several amphibious operations, including Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and earned two battle stars to add to the four awarded to her earlier. Decommissioned on 29 June 1946, the Biscayne was transferred to the U.S. Coast Guard and was stricken from the Navy Register on 19 July 1946. Renamed the Dexter, the erstwhile stopgap flagship was returned to the Navy on 9 July 1968, and ultimately was sunk as a target.

The smallest of the amphibious-force flagships in the U.S. Navy during World War II, the Biscayne carried out her wartime duty wherever she served with great distinction, and in recognition thereof, received the Navy Unit Commendation.