The First Tentative Steps

In an example of the ironies that pervade history, the initial development of naval aviation resulted from the efforts of three unlikely proponents: a civilian pilot not fond of the water, an officer whose naval service began just seven years after the Civil War ended, and a motorcycle racer-turned-airplane manufacturer. Yet in Eugene Ely, Captain Washington Irving Chambers, and Glenn Curtiss, the Navy benefited from a daring aviator at the controls, an administrative champion within the naval bureaucracy, and an innovator developing cutting-edge flying machines. Those three ingredients have remained a constant in naval aviation over the course of its first century, a period marked by brilliant technological achievement, tactical evolution, an adventurous spirit, and heroism of the highest order.

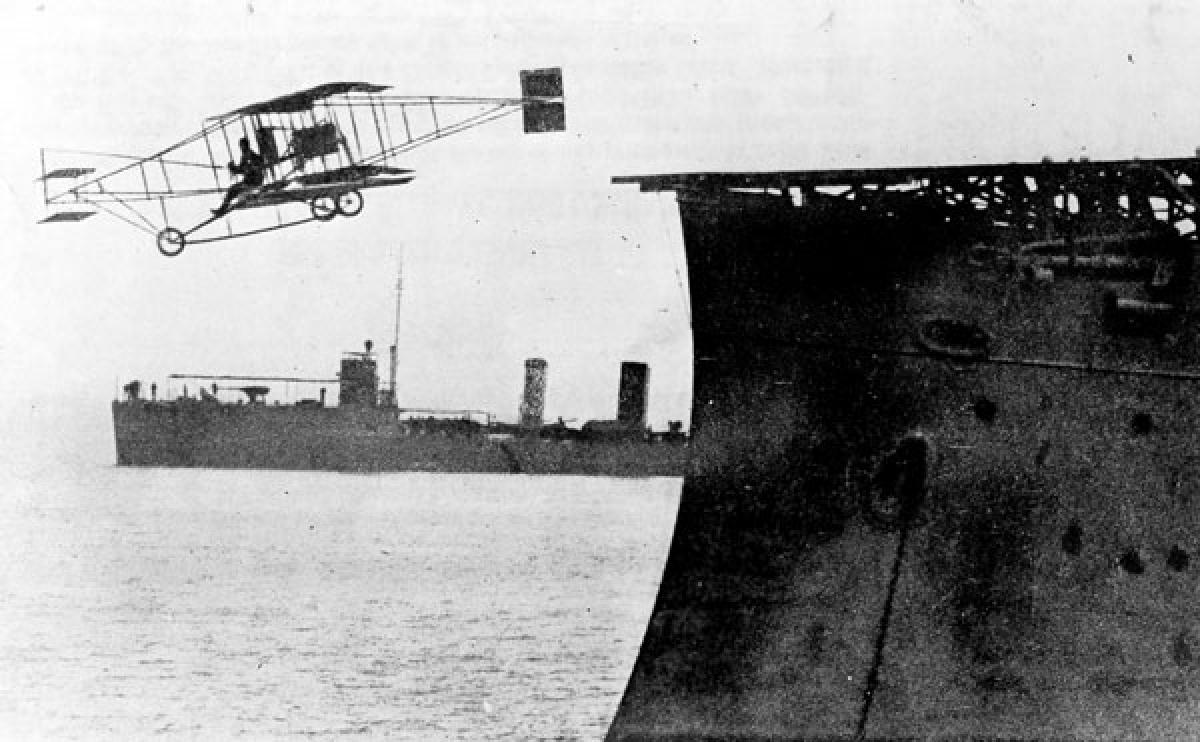

Chambers, Curtiss, and Ely reached the first milestone in the autumn of 1910. The site was Hampton Roads, Virginia, location of a previous naval revolution; during the Civil War, the first battle between ironclad ships was fought there. On 14 November, Ely successfully flew a Curtiss pusher from a makeshift wooden deck erected on the scout cruiser Birmingham. Two months later, Ely made the first landing on a similar deck constructed on board the armored cruiser Pennsylvania anchored in San Francisco Bay. With hooks on the underside of his aircraft snagging a series of ropes that traversed the deck and were weighted down by sandbags, Ely performed a primitive arrested landing that foreshadowed those destined to occur on the decks of true aircraft carriers.

Ely’s dramatic achievements, however, did not assure a place for naval aviation in the U.S. Fleet. Officers of the day did not look favorably on diminishing the firepower of their battleships and cruisers by constructing wooden decks on them. More far-reaching in the effort to integrate aviation into Fleet operations was another flight to the Pennsylvania that occurred on 17 February 1911, when Glenn Curtiss piloted a hydroaeroplane out to the ship, landed alongside, and was hoisted aboard. A short time later, a crane lowered his flying machine onto the water, from which he took off and returned to shore. It would be on the wings of seaplanes, not land planes, that the foundation of U.S. naval aviation rested.

On 8 May 1911, the date the U.S. Navy celebrates as the birthday of naval aviation, Chambers prepared requisitions for the purchase of the service’s first two aircraft. During the ensuing years preceding World War I, the Navy added an array of airplanes to its inventory, all either built to fly from the water or converted to that configuration. Among the more successful were flying boats, the appearance of their hulls likened by some to wooden shoes, and seaplanes with floats. Others were unorthodox, notably a design by the Gallaudet Engineering Company of Connecticut in which the engine and propeller were located in the middle of the plane’s fuselage.

With the procurement of aircraft came the assembly of personnel. The first naval aviators were junior officers, a number of whom were drawn to flying after witnessing European aircraft during cruises overseas. They were men willing to take a risk professionally, turning their backs on tried-and-true career paths to participate in an endeavor whose success was uncertain. Out of necessity, given the primitive airplanes of the day and the fact that aviation was just beginning to be understood, they were daring. Seven of the first 20 naval aviators lost their lives in Navy aircraft accidents, a testament to the hazards of flying during that period.

Naval aviation did not have a permanent base of operations until aircraft and personnel arrived at Pensacola, Florida, in January 1914 to establish an aeronautic station. The first aviators and their support personnel would make significant strides in the years before America’s entry into World War I. During exercises with the Fleet, notably off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, they demonstrated the ability of aircraft to improve the accuracy of warship gunfire by spotting its fall. Also of significance to the future of aircraft in the sea service, naval aviators conducted successful catapult tests ashore and from the decks of ships and experimented with aerial bombing. When the Navy was called into action to occupy Vera Cruz, Mexico, in April 1914, naval aircraft from Pensacola deployed to the scene and flew observation and scouting missions that marked the first combat operations by U.S. airplanes.

While such experiments and operations helped aviation gain a foothold in the Navy, events across the Atlantic pointed to the dawning of the air age in warfare. Despite the fact that Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels had proclaimed in 1914, the year World War I began, that “aircraft must form a large part of our naval force for offensive and defensive operations,” by April 1917 the Navy’s entire aviation force consisted of fewer than 300 personnel and just 58 aircraft, none suitable for combat. That same month, the United States declared war on Germany. The decisive test for fledgling U.S. naval air power would occur in Europe during the Great War.During 2011 these and other photographs tracing the history of U.S. naval flight can be viewed at www.usni.org. Follow the Naval Aviation Centennial links. Slideshows change monthly.