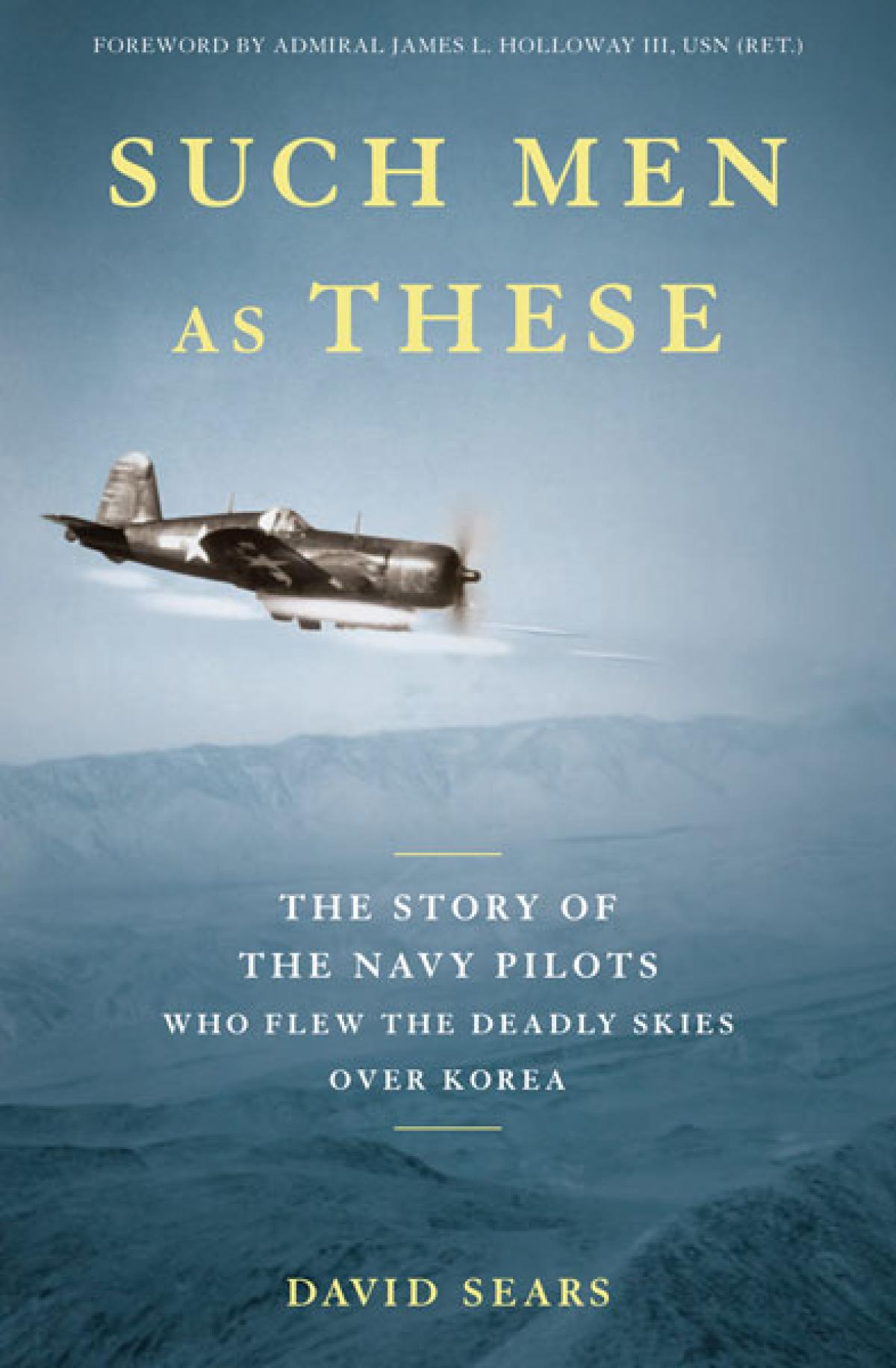

Such Men as These: The Story of the Navy Pilots Who Flew the Deadly Skies over Korea

David Sears. Foreword by Admiral James L. Holloway III, U.S. Navy (Retired). Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2010. 432 pp. Maps. Illus. Notes. Gloss. Bib. Appen. Index. $25.

Reviewed by Hill Goodspeed

It is ironic that for decades the most recognized account of U.S. naval aviation’s operations in Korea has been a work of fiction. James Michener’s book The Bridges at Toko-Ri and the film adaptation, starring William Holden, Mickey Rooney, and Grace Kelly, traced the tale of recalled Naval Reserve aviator Lieutenant Harry Brubaker and his struggle to overcome both the enemy and his resentfulness over having to serve in an unpopular war. In Such Men as These: The Story of the Navy Pilots Who Flew the Deadly Skies over Korea, author David Sears provides background on Michener and the famous author’s personal journey as he researched and wrote the novel. This serves as a backdrop for Sears’ words about the real-life Lieutenant Harry Brubakers flying from carriers off Korea.

As the title suggests, Navy pilots of carrier-based fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft are the focus of the book, and it is in the telling of their individual stories that Sears is at his best. His writing style lends itself to effective narrative history, though without detailed endnotes his descriptions of the emotions felt by some of the subjects at particular moments leave the reader curious about his sources. Although he covers stories that are in some cases well known to students of naval aviation—among them that of Ensign Jesse Brown, the first African-American to complete the Navy’s flight-training program—Sears’ recounting of the information and the weaving of individual experiences into the fabric of the times results in an entertaining and informative read.

Such Men as These is not a definitive history of naval aviation during the Korean War. Discussions of strategies and tactics are only used to place the individual subjects within the context of the times. Yet over the course of the book Sears devotes attention to areas overlooked in more expansive academic histories, but that are important in fully capturing the lives of those who fought in the war. One example is Japan’s changing culture between the end of World War II and the beginning of the Korean War, a transformation that affected those in naval aviation given that the carriers of Task Force 77 replenished at Yokosuka and Sasebo, Japan, their crews and embarked air groups interacting with Japanese civilians while on liberty. His discussions of the nuances of the holdover World War II aircraft and first-generation jets that waged the naval air war are also informative, as is his contrasting the Korean War experience with that of World War II. He includes the cycle of operations and the dissimilar geography and weather conditions, especially in winter.

While naval aviators’ struggles in the prisoner-of-war camps of North Vietnam have been the subject of numerous memoirs and histories, the experience of those shot down during the Korean War has not stimulated similar attention. Sears dwells at length on what those held captive in North Korea endured, particularly the psychological and emotional torture they faced. Indeed, these sections are among the most interesting in the book.

Occasional errors do appear. Admiral Marc A. Mitscher did not, like Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. and Vice Admiral John S. McCain, receive his wings in middle age, but became a pioneer naval aviator in his late 20s. In addition, the S-51 (HO3S) helicopter flown during the war was not, as Sears states, “the first model put in use by the armed forces.” In naval aviation, that distinction belongs to the R-4 (HNS), which operated with the Army and Coast Guard (a wartime component of the Navy) during World War II. Yet these inaccuracies do little to detract from the overall story told in the pages of Such Men as These, which provides a fitting remembrance of one group of men who waged the “Forgotten War.”

Hellcats: The Epic Story of World War II’s Most Daring Submarine Raid

Peter Sasgen. New York, NY: NAL Caliber, 2010. 320 pp. Maps. Illus. Intro. Notes. Bib. Index. $26.95.

Reviewed by Carl LaVO

In late June 1944, Navy Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood presented to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, a plan for the submarine invasion of the impenetrable Sea of Japan. Under Lockwood’s guidance, naval weapons scientists had perfected a new type of sonar that would enable subs to penetrate the minefields that guarded access to the sea. “Eventually, Admiral, with this new sonar, we’ll crack the Sea of Japan without losing a ship or man to the minefields,” said Lockwood, commander of the Pacific submarine force.

Things didn’t work out quite as he envisioned. In June 1945, Operation Barney enabled nine “Hellcat” subs to evade the mines and attack enemy vessels. However, one of the boats, the USS Bonefish (SS-223), was lost with her 85-man crew. In the aftermath, Lockwood’s controversial gamble drew much criticism as a needless stunt that sacrificed the Bonefish, given that the Pacific war was all but over.

The two central characters in author Sasgen’s dramatic account are Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Lott Edge, captain of the Bonefish, and Lockwood, the charismatic admiral who molded the Pacific submarine force that overcame scandalous torpedo problems to eventually strangle Japan’s merchant marine, isolate the island nation, and sink much of its navy by war’s end. By the spring of 1945, the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet was closing in on Japan, while American aircraft were reducing Japanese cities to ashes. With few targets for the submarines to go after, Lockwood faced the bleak prospect that his vaunted undersea force might become a footnote in the collapse of Japan. He was determined to make one last dramatic gambit by plotting a risky venture: send FM sonar–equipped submarines into the Sea of Japan. The boats were deployed as three wolf packs of three subs each under the joint command of Commander Earl T. Hydeman, captain of the USS Sea Dog (SS-401). He christened his group “Hydeman’s Hellcats”—a fitting moniker, given that FM sonar’s loud alarm of approaching mines was called “hell’s bells” by crewmen.

Commander Edge provides the poignant human-interest focus for Sasgen’s book. Readers learn early on that the Bonefish disappeared, but under what circumstances remains a mystery until the very end. The majority of the book builds a portrait of Edge and his tightly knit family while exploring how Operation Barney came to be and its tragic conclusion—foretold by a weary Edge in a letter to his wife: “Feeling the war is approaching the downhill side, as far as time is concerned, is no help to any of us either. Rather there’s the feeling that we’ve been lucky enough to survive so far; it would be such a shame not to last for the remainder and thus live through the whole thing.”

Many critics after the war believed Lockwood’s primary motive for Operation Barney was to avenge the loss of the USS Wahoo (SS-238) and hotshot skipper Commander Dudley W. “Mush” Morton in 1943 in the Sea of Japan. Morton was the prototype of the aggressive sub commander Lockwood was looking for to revolutionize the fighting spirit of the “Silent Service.”

After the war, the admiral admitted to having this motive. But he also was determined to point to a future in which subs equipped with the new sonar could operate safely in mine-laced seas, even though he knew that the equipment at the time was rated to be 80 percent effective. As Sasgen notes, the admiral had adopted the mantra of Army General George S. Patton: A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan next week.

Sasgen vividly recounts the pulsating drama of the Hellcats threading their passage between the mines. Japan was clearly caught off guard once the subs entered the Sea of Japan, where they proceeded to sink 28 vessels totaling 57,058 tons—a credible score. However, seen in the context of the atomic bombs dropped just a few weeks later (of which Admiral Lockwood had no prior knowledge), Operation Barney did little to affect the war’s outcome. Thanks to the persistence of Edge’s widow, Sarah, who questioned the need for the operation after the war, the sad story of the Bonefish’s demise is finally revealed.

Hellcats is well-written, engaging, and fills in the last chapter of the Navy’s submarine war against Japan.

Turtle: David Bushnell’s Revolutionary Vessel

Roy R. Manstan and Frederic J. Frese. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2010. 400 pp. Illus. Appen. Notes. Bib. Index. $24.95.

Reviewed by Don Walsh

Since the late 18th century there have been several book-length publications on David Bushnell (1740–1826) and his all-wooden submarine Turtle, and a few replicas of the boat have been built. All were speculative, as no contemporary images of the original are known to exist. This book describes the extensive historical research, construction project, and dive testing of the most accurate replica built to date.

In 1771 Bushnell was a student at Yale when he developed the idea for a submarine that could be deployed against Royal Navy ships. With the backing of powerful supporters, including Benjamin Franklin, and with the approval of General George Washington, the submersible was completed and tested in 1776.

On the night of 6 September 1776, Sergeant Ezra Lee maneuvered the small craft out to the anchorage in New York Harbor, where the Royal Navy flagship Eagle was anchored. It was hard work as he manipulated the hand-operated controls and foot pedals to propel the semisubmerged, egg-shaped sub into attack position. Adding to his difficulties was a fairly strong current.

A 130-pound black-powder explosive charge, or torpedo, was to be attached to the target by use of an auger and a screw fitting. Lee managed to get under the Eagle, but when he tried to attach the explosive to the hull, it would not set properly. After several tries to get the auger to make a hole in the hull he gave up, fearing that he would be detected at dawn.

As he was returning to the dock four miles away, Lee realized that he had been observed. He jettisoned the torpedo after setting its fuse, and when it detonated the pursuers gave up. The sub was used for a few other missions against the anchored British ships, but none were successful.

Bushnell was eventually drafted into the Army as an officer doing civil engineering work. His submarine career had ended, and the Turtle was lost in the mists of history. There are no reliable accounts of her final fate. However, there were a lot of contemporary writings on her design and specifications.

This book’s authors, Roy Manstan and Frederic Frese, intended to build an operational replica of the Turtle using all the documentation they could find in historical records. Frese was an instructor in technical arts at Old Saybrook High School in Connecticut. In 1976, he had built the American Turtle replica for the American Bicentennial celebration. As described in this book, his 21st-century Turtle would be a student project. Project codirector Manstan was a mechanical engineer employed at the Navy’s Undersea Warfare Center at Newport, Rhode Island. He would become the Turtle’s test pilot for her first dives in 2007.

While at least two other Turtle replicas had been built, this project was unique in the amount of research that was done to ensure the submersible would be as accurate as possible. In November 2007, the replica was launched by her proud team. A successful test dive confirmed that they had indeed duplicated Bushnell’s creation of the world’s first combat submarine.

However, this book is much more than a “project report.” It is also rich in the history of the time when the first Turtle was developed and used. Then Frese and Manstan used that history to replicate America’s first combat submarine.

Historical Dreadnoughts: Marder and Roskill: Writing and Fighting Naval History

Barry Gough. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing, 2010. 366 pp. Illus. Notes. Bib. Index. $70.

Reviewed by Kenneth J. Hagan

The distinguished Canadian historian Barry Gough regards two preeminent 20th-century scholars of the modern Royal Navy as “historical dreadnoughts” because of the mass and power of their writing. One was British naval Captain Stephen Roskill; the other was American academic Arthur Marder. In Gough’s interpretation, Marder revolutionized the study of the British navy. He was a protégé of Harvard Professor William L. Langer, and on the occasion of Langer’s retirement in 1969 Marder eulogized him “for steering me into the then virginal field of naval history of the non-‘drum-and-trumpet’ sort, where I have been so happy all these years.”

Beginning with The Anatomy of British Sea Power in 1940, Marder published six volumes detailing the workings of the Royal Navy as a political-military institution during the period from 1880 to 1919. In compiling that multivolume opus he demolished naval history as a narrow field with a myopic fixation on the glorious legacy of Nelsonian broadsides. The guns, armor, and maneuvering of ships did not count for Marder. What mattered was the naval and governmental “infrastructure,” which, through all of its institutional intricacies and interpersonal complexities, had deployed the gunners. The passageways of Whitehall now became more important than the gun decks of HMS Victory.

For an American to have reshaped the way scholars and others analyze and interpret the ingrown and complacent Royal Navy was an unprecedented coup, and to their great credit the British heaped laurels on Marder. There was, however, one British navalist who did not echo his countrymen’s praises. Retired Navy Captain Stephen Roskill was as prolific a historian as Marder, but he suffered from a competitive disadvantage. Some of his works were written as official histories. Gough sympathetically observes, “The story of his [three-volume] War at Sea stands as a chapter in how the state tries to own its history and yet how an individual historian, such as Roskill, can shape that history.” Gough traces in detail and with compassion the hurdles Roskill had to overcome in writing his fine history of the Royal Navy in World War II, and he isolates the completion of the book in 1961 as the moment at which Roskill became a fully independent historian and one in competition with Marder.

Historical Dreadnoughts meticulously describes how Marder and Roskill initially confided in one another and exchanged their ideas and manuscripts. They fell into acrimonious mutual criticism when their studies of the Royal Navy after World War I began to overlap. The professional and personal decline from collegiality into animosity is fascinating, but the greater worth of this superb book lies in the author’s meticulous documentation and exposition of how two marvelously prolific scholars produced their works.

Marder’s case is the more intriguing of the two because of the amazing and not fully explicable ways in which he was able to insinuate himself into Admiralty records that remained closed to other scholars for many years after he had examined them. Unremitting persistence seems to have been one key, but the reader—and apparently Barry Gough—emerges with a sense of wonderment that this impertinent and preternaturally dedicated American could have cracked open such an inner sanctum of national and institutional rectitude. It must be partly for this reason that Gough rates Marder as a greater historian than Roskill: “Marder still commands our attention, for the fine quality of his work and the freshness of the evidence he presents.”

Gough’s case is persuasive, but as he knows, several historians on both sides of the Atlantic have criticized Marder for incomplete use of the Admiralty records and for excessive kindness to the naval commanders whose lives he examined. Gough admonishes the unnamed revisionists: “Some may make it their life’s work to bring him down, or to score points at his expense, but to challenge his pre-eminence they will have to develop a better vision of their own. . . . Mere sniping from the wings will not suffice.”

In its prodigious scholarship, elegant writing and humane insight into the working lives of Roskill and Marder, Historical Dreadnoughts presents the 21st-century critics with a daunting challenge, which Gough understands will be taken up: “All great historians and practitioners of the historian’s craft face critics.” He was writing about Marder and Roskill, but he was speaking of himself.