"It is unbelievable," Lieutenant Commander Reinhard Hardegen said quietly to one of his lookouts on U-123 in Rhode Island Sound on the evening of 14 January 1942. Lights around them blazed in all directions. "I have the feeling that the Americans are going to be very surprised." Moments later Hardegen sank the tanker Norness, and then four days later off Cape Hatteras—again against an illuminated coastline—he sank four more ships. In January 1942 the Battle of the Atlantic struck America, with catastrophic results for the Allies. But Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat) turned out to be just another phase in the longest and most complex campaign of World War II.

The Battle of the Atlantic started on 3 September 1939 when U-30 sank the small British liner Athenia west of Ireland, and it ended on 7 May 1945 when U-2336 sank two small steamers in the North Sea off Newcastle, England. Attacks on merchant shipping by German submarines remained the one constant in a struggle whose objective and methods varied enormously over those 5?? years. During the first ten months of the war at sea, Germany sought, in whatever way possible, simply to throw off Allied strategy while supporting their own. Raiders dispatched to the far corners of the Atlantic and into the Indian Ocean achieved some notable feats. Modern, fast, and powerful German surface units could be—and were—enormously disruptive; this was understood to be part of the strategy. But the overall impact of German attacks on Allied shipping in 1939-40 was minimal.

The war at sea began in earnest in the summer of 1940, after Western Europe fell to Germany. In a stroke, Britain was virtually surrounded by the Axis. In late September the Germans shifted from trying to win air supremacy over Britain to area bombing of its cities, as a strategy of attrition and blockade asserted itself. Britain, which imported about half of its food and most of the resources it needed to wage war, seemed uniquely vulnerable to such a strategy. It was also the hub of a vast empire and needed to move men and equipment around the globe. Over the winter of 1940-41, the Germans for the first time had a clear and perhaps obtainable strategic objective in the war at sea.

German control of Western Europe effectively shut down Britain's main seaports on her eastern and channel coasts, London in particular. Luftwaffe planes flying from bases in France, Norway, and the Low Countries made coastal routes untenable, while long-range Fw 200 Condors patrolled deep into the Atlantic. Britain was forced to reorient cargo-handling capacity to western ports, which in turn were devastated by German bombing over the winter.

Early Menaces to Allied Shipping

Large German warships were a key component of this comprehensive assault on British imports. In mid-December 1940 the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper sortied into the Atlantic, the first of a series of major deployments that would culminate in the famous and ill-fated voyage of the battleship Bismarck in May 1941. On Christmas Day the Admiral Hipper stumbled across the outbound troop convoy WS 5A, escorted by three cruisers and the old carrier HMS Furious. The Hipper beat a retreat, and then slipped briefly into Brest. By late January she was back to sea, this time north of the Azores, where coordinated surface, subsurface, and air attacks on shipping were planned. The coordination was effected by Admiral Karl Donitz, head of the U-boat service who in January 1943 would also become commander-in-chief of the German Navy, or Kriegsmarine.

The combined attacks peaked in February 1941, after the admiral had gained control of Luftwaffe Condor units, when convoys HG 53 and SL(S) 64 were attacked. HG 53 (homeward bound from Gibraltar) was found by U-37, which sank two ships. Homed onto the convoy, six Condors sank a further five vessels, while the Hipper sank a straggler. On 12 February, the cruiser set upon SL(S) 64, a slow convoy out of Sierra Leone, which lost seven of its 19 vessels to the warship's guns. Meanwhile, farther north the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau slipped into the Atlantic in late January 1941, starting a two-month cruise. Although they failed to attack a single convoy, the two raiders sank independently routed shipping, disrupted convoy sailings, and played cat and mouse with the Royal Navy before retiring to Brest.

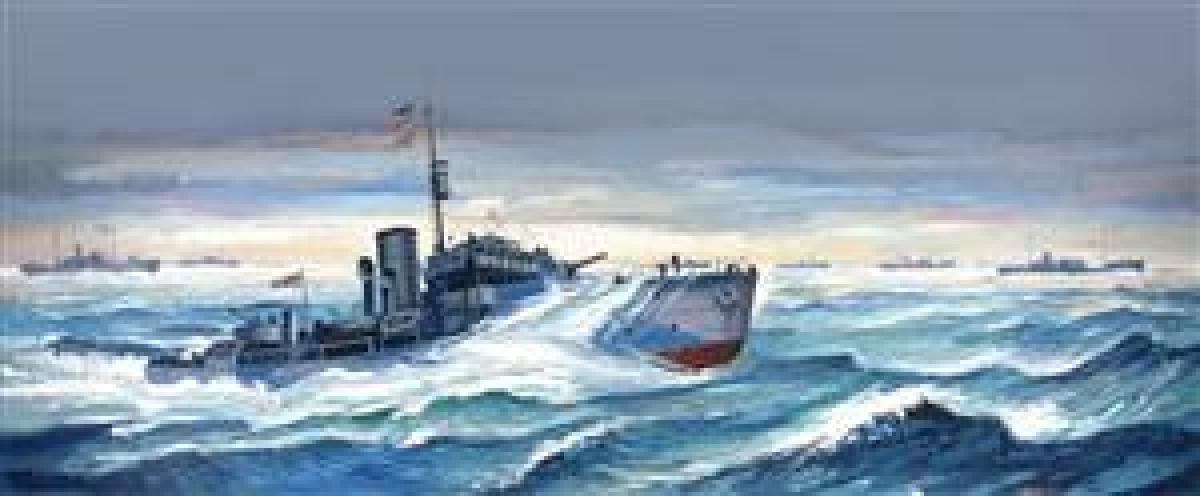

The failure of the British to run any of these marauders to ground in early 1941 owed much to the vastness of the ocean, the vileness of North Atlantic weather, and the darkness of long winter nights. The Bismarck, however, was cornered and sunk on 27 May 1941. Although historians have paid little attention to these prolonged and disruptive patrols by German surface warships, they could not be treated lightly by the British and were the prime focus of Royal Navy operations over the winter of 1940-41.

The Wolf Pack: Key to U-boat Success

Even during this period, however, the smaller vessels—the U-boats—did the lion's share of sinking Allied tonnage. German submarine captains dubbed it their "Happy Time." The U-boat success derived from the adoption of new tactics and the exploitation of crucial weaknesses in the Allied convoy system. Through the first year of the war, aces like Otto Kretschmer, Gunter Prien, Joachim Schepke, and Fritz Lemp operated independently and averaged about 25 sinkings each per month. But Donitz believed that submarines could be used more aggressively, in groups against escorted convoys.

The idea was simple enough. There were three key problems associated with U-boats trying to attack a convoy in the broad ocean: initial location, assembly of the pack around the convoy, and the actual attack. Donitz's solution to locating convoys was to deploy U-boats in lines perpendicular to shipping routes and control their movements from his headquarters by radio. U-boat commanders had to transmit their noon positions daily, and weather reports when asked. In return, Donitz's headquarters, U-boat Command, shifted the positions of the lines based on the latest intelligence.

If all went right, a line would snag a convoy and report its position, course, and speed. Initial contact was usually visual, but U-boats could use their sonar to get a general fix on machinery noise, and as the war progressed, they could do much the same with the escorts' radar signals. In the evolving contest between convoy routers and German operational plotters, initial contact was often the most difficult task and many a convoy slipped around or through a patrol line undetected.

Once contact was established, the U-boat making the sighting was usually tasked as a shadower, sending regular position reports and transmitting a medium-frequency direction-finding (MF/DF) signal so the rest of the pack could home-in. The process of collapsing the pack on the convoy was directed from U-boat Command, which tracked and recorded each contact report as the submarines found the target. All of the extensive radio traffic associated with these first two phases of a pack operation was vulnerable to intercept and to plotting by direction-finding stations on shore. Donitz, however, was fully confident that the system was foolproof under operational conditions.

Intelligence the Allies gained by "DFing" signals sent by U-boats at sea was perhaps a greater concern. It was possible to accumulate important data from studying the pattern of operations and to obtain through land-based DF stations a rough estimate of the number and general location of U-boats at sea. This kind of plotting and traffic analysis was also unavoidable. Moreover, in 1939 shore-based stations could only estimate positions to within about 50 miles, and since no one had yet developed a direction-finding set small enough for a ship, Allied DFing could not produce tactical intelligence. In any event, U-boat attacks would reveal the boats' presence. So the reliance on radio communications was a trade off, and in 1940 the benefits were almost entirely on the German side.

U-boat radio signals were enciphered using highly sophisticated Enigma machines. Each employed a series of alphanumeric rotors connected to cables that were inserted into a socket board. The alignment of the rotors and the cable connections changed daily according to a codebook so that when the operator struck a number or letter on the machine's keyboard a totally different letter or number would light up on its display panel. The combination of three or four rotors and the cable connections produced tens of millions of possible permutations. Donitz understood that it was possible to decipher signals encrypted by Engima machines but believed it would never be done quickly enough or in sufficient volume to affect operations.

The final act of the pack operation was the attack—when U-boats were cut loose from their wireless "leashes" and the "sea wolves" earned their nickname. Ideally, Donitz assembled as many U-boats as possible around the convoy before turning them loose. There was no attempt to coordinate the pack attack at the tactical level; it was just too impractical. Rather it developed in accordance with local conditions, coming at night and preferably from the convoy's dark side. That allowed the subs to approach against a totally black sky while the convoy lay silhouetted against moonlight. Attacks often came in waves, U-boats trimmed down so that only their conning towers remained above water, racing through the escort screen and into the columns of ships. The objective during the high-speed run was to fire all four bow torpedoes and, if possible, the two stern tubes. Once the "fish" were expended, the U-boats either escaped astern of the convoy or dove into the tangle of wakes left by the merchant ships.

In the fall of 1940, the new Wolf Pack strategy and tactics took full advantage of key weaknesses in the Allied system of trade defense. It was understood that coastal zones were primarily threatened by U-boats, typically operating alone and submerged. Antisubmarine escort was therefore provided inshore on both sides of the Atlantic. In the ocean's broad reaches, east-bound convoys were protected against raiders by cruisers, old battleships, and even submarines, and west-bound convoys were dispersed once beyond the designated submarine danger zone. Thus, transatlantic convoys were particularly vulnerable to U-boats beyond the range of their escorts, while the escorts themselves were never expected to deal with more than one or two submarines at a time.

Pack Successes and British Countermeasures

The Wolf Pack system was not entirely perfected when six U-boats intercepted Convoy SC 7 on 16 October 1940. The slow convoy of 34 ships from Canada had just been joined by its eastern antisubmarine escort of three vessels, with support from a long-range Royal Air Force S.25 Sunderland flying boat. In fact, U-48, which made the initial contact and immediately sank two ships, was driven off by the bomber. Donitz hurriedly assembled a pack, and the next night it attacked. What followed was something akin to a shark feeding frenzy; even the Germans had trouble figuring out who did what as five U-boats roamed through the convoy at will. By the time it was over, 22 ships had gone down—the highest loss rate for any North Atlantic convoy during the war. On 20 October a new pack of five U-boats (some from the SC 7 battle) fell on Convoy HX 79, screened by no less than 11 escorts, including two destroyers and three corvettes, and sank a further 12 ships.

These pack attacks bedeviled the Allies all through the winter of 1940-41, but solutions were soon obvious. Among the most important were the development of radar for both aircraft and small vessels, especially the new 10-cm sets that could detect U-boats on the surface, and shipborne high-frequency direction-finding (HF/DF, or Huff/Duff) receivers. The Royal Navy's Western Approaches Command (WAC) was moved from southern England to Liverpool in February and given responsibility for defending trade in the North Atlantic, including operational control over RAF Coastal Command aircraft in their zone. Naval and air force bases were being constructed in Iceland to extend antisubmarine protection into the mid-Atlantic, and on 6 March 1941 Churchill declared his government's resolve to win this "Battle of the Atlantic," pouring further resources into the mix.

WAC, meanwhile, stabilized escort-group composition, leadership, and training, and developed standardized tactics and doctrine for antisubmarine operations. Its first major tactical pamphlet, "Western Approaches Convoys Instructions," promulgated in April 1941, made "safe and timely arrival" of the convoy the primary task of the escort; sinking U-boats was a secondary responsibility.

Improving skills and weather, as well as radar, gave the British a major victory in mid-March, when two of Germany's great U-boat aces—Prien and Schepke—were killed at sea and a third, Kretchsmer, was captured. Their removal from the scene effectively ended the first Happy Time, and with the withdrawal of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau to Brest, so too the immediate threat that the Kriegsmarine would cut off Britain. British anxiety was further eased by the United States' declaration of a larger neutrality zone in April 1941, one that included Iceland and much of the mid-Atlantic. American forces would now patrol half of the North Atlantic and openly broadcast the positions of Axis ships and aircraft.

The spring of 1941 also brought the completion of transatlantic antisubmarine escort of convoys. In June the burgeoning Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) established a base in Newfoundland to fill the final gap between local Canadian escorts and British forces then using Iceland as a relay point. The RCN's Newfoundland Escort Force was a ragtag assembly of new corvettes, a handful of ex-U.S. Navy four-stack destroyers, green crews, and a few first-rate destroyers, but as the WAC commander-in-chief observed, it "solved the problem of the North Atlantic convoys." Everyone hoped they would not have to fight and in the summer of 1941 British breakthroughs in decrypting Enigma-enciphered radio messages virtually ensured that convoys were generally routed clear of danger.

America Gradually Enters the Battle

The most important development in the Atlantic war in the late summer of 1941 was the increasing involvement of the U.S. Navy. Liaison between the Americans and the British Commonwealth on trade protection, facilitated through Ottawa, was already excellent. In fact, the Canadians ran a complete naval control of shipping (NCS) network throughout the continental United States. The U.S. Navy was drawn into this network during 1941. Canada provided training, confidential books and special publications related to trade, as well as an NCS specialist who was sent to Washington.

It was thus a short step, at least organizationally, to shift the American Navy from a neutral participant in the Atlantic war to an active one when Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt met in Argentia, Newfoundland, in August 1941 for the Atlantic Conference. There, it was agreed, among many other things, that the United States would escort convoys inside its new strategic zone—basically from Iceland west—thus freeing Royal Navy ships for other duties. Warships of the the Atlantic Fleet's Support Force (later redesignated Task Force 24) would escort fast trade convoys between the limits of local Canadian escort and Iceland, for the time being leaving slow convoys in the area under Canadian escort. With this, the Royal Navy relinquished control of transatlantic convoy escort operations west of Iceland to the U.S. Navy. The move also placed Canadian naval and air combat operations under command of a quite-alien, and still-neutral, power. In August 1941 that did not seem like much of a problem, and getting the Americans into the campaign was clearly worth it.

By the time the U.S. Navy began escort operations in the northwest Atlantic on 16 September, the U-boat campaign had swung back into the mid-ocean. After a summer of success off the Azores, Donitz adopted a new deployment form for the North Atlantic in an attempt to cope with the success of Allied evasive routing. Instead of fixed patrol lines, his U-boats arrayed themselves in loose concentrations that drifted in accordance with intelligence estimates. One of these snared SC 42, a slow convoy escorted by a small Canadian group, in early September south of Greenland. In a three-day running battle, the convoy lost 15 ships before reinforcements arrived from Iceland. Weakly escorted convoys were no match for powerful Wolf Packs, and the Canadian Navy was obliged to increase the average size of Newfoundland Escort Force groups from four to six ships in an attempt to cope.

The fall of 1941 campaign in the North Atlantic drew the United States into a shooting war, much of which focused on the slow convoys. Escorted by poorly equipped and hastily trained Canadians, they were incapable of effective tactical evasion when under attack. Just four days after the Americans started escort duty, five U.S. Navy destroyers went to help Convoy SC 44 and its Canadian escorts, which were beset by a Wolf Pack. By the time the tin cans arrived, the battle was essentially over. Four merchant ships and the corvette Levis were sunk, but the Americans were now engaged. If there was any doubt about this the torpedoing of the USS Reuben James (DD-245) on 31 October by U-552 put it to rest.

The U.S. Navy also learned two lessons from its experience in the fall of 1941 campaign: Weakly escorted convoys were a disaster waiting to happen, and the real problem was the U-boats; kill them and everyone was safe. These views played to the Navy's Mahanist predilections, and to a general North American view (shared by the Canadians, much to Britain's dismay) that the North Atlantic was a combat zone and the Allied navies' task was to fight the enemy. Not surprisingly then, when the U.S. Atlantic Fleet issued its first convoy escort instructions in November 1941, Lanflt 9A, safe and timely arrival of the convoy—the cardinal objective of British escort operations—came dead last on the list of tasks. The American escort's first task was to find and destroy the enemy. This proved remarkably hard to do, which was, of course, why the British had given up on it.

Ultimately, the recipe for defending a convoy against a Wolf Pack, and for sinking U-boats in the process, was worked out by the British in November and December 1941 west of Gibraltar, in the so-called Azores air gap. There, they combined modern 10-cm radar; large, well-trained and well-lead escort groups, and carrier-based and very long range (VLR) airpower to exact a toll on German submarines. Before these methods and the newly developed shipborne Huff/Duff sets could be applied in the North Atlantic, however, Germany declared war on the United States and the assault on shipping in the western hemisphere began.

Carnage Along the East Coast

The 1942 campaign in the western Atlantic primarily involved the deployment of individual U-boats inshore. The Anglo-Canadian response to this type of threat was, in modern jargon, to shape the battle space to make the German task difficult if not impossible. This was done by operating coastal convoys under an air umbrella, which prevented packs from forming, kept U-boats down, and limited their search capacity. Under these circumstances, even a small naval escort for a convoy was sufficient. At best, a determined submariner might get in one successful attack against an inshore convoy, but no more. The system was particularly effective in areas where a wide stretch of open ocean allowed for a wide track of possible routes under a broad corridor of local air support.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Navy did not initially see it this way. Fearful of weakly escorted convoys, Americans refused to institute a coastal convoy system, while pressure from vacation spots kept the lights burning along the shoreline. Instead, the Navy established a series of patrols along designated routes and tried to move dispersed shipping along them. By 1 April, 80 small ships and some 160 aircraft between Maine and Florida were engaged in these operations. The results were disastrous. Routine patrols and dispersed shipping allowed U-boats to operate at leisure, confident that they would not be interrupted and assured that another target would come along like clockwork.

The Anglo-Canadians watched in stunned disbelief. Given the extent of British and Canadian control of shipping in the western hemisphere, they could have organized convoys in the American zones from the outset. In fact, the first convoys in the U.S. Eastern Sea Frontier were Canadian. The Halifax to Boston system began in late March. By May Canadian tanker convoys were running through the U.S. coastal zone to the Caribbean without loss despite attempts by the Germans to mount pack operations against them.

There were still no American coastal convoys in early May, as the U-boats spilled into the Gulf of Mexico and began wreaking havoc on American tanker traffic. Supported by a submarine tanker, which refueled and rearmed the submarines, 19 U-boats remained on station. In May alone they sank 115 ships in the western Atlantic, about half of which were in the Gulf. The toll for June was 122. In those two months, a million tons of shipping was lost in the American zone—half the previous year's total.

By mid-May the first American coastal convoy finally began, steaming between Hampton Roads and Key West. As the system spread, and the air support improved, losses diminished and U-boats moved on to greener pastures. In July and August the hunters drifted through the Caribbean, and by late summer to the South American coast. The convoy system followed and drove them out. But the Allies paid a very steep cost for this Pyrrhic victory: six million tons of shipping lost in 1942 to U-boats alone, three times more than the previous yearly averages.

The extension of the convoy system southward and the need to respond to unchecked Japanese expansion in the Pacific gradually weakened the transatlantic escort system between Newfoundland and Britain. By the summer, British, American, and Canadian forces were all spread thinly. But the U.S. decline in the mid-ocean was quickest and most pronounced.

U-boats Gain the Mid-Atlantic Upper Hand

By May the U.S. Navy's role was down to a few Coast Guard cutters and the occasional destroyer in nominally American escort group A3 (whose composition was largely Canadian corvettes). The Royal Navy again took over most of the fast convoys, while most of the forces now commanded by Task Force 24 were actually Canadian. With Iceland abandoned as a relay point, convoys now ran straight between Northern Ireland and Newfoundland. Corvettes and destroyers could just make it if they were not too active and the convoy routing was direct. All this created a unique opportunity that the Germans moved to exploit in the late summer of 1942.

When Admiral Donitz shifted the weight of his forces back into the mid-Atlantic he found convoys tied closely to the far-northern great circle route and escorted by much-reduced and weary groups. The Canadians still escorted the slow convoys and had not yet been fitted with modern equipment. Their first-generation radar could be DFed by the U-boats' new radar detectors; they had too few destroyers, whose tactical speed was crucial; and only one Royal Canadian Navy escort had been fitted the new Huff/Duff set. Moreover, since February the Allies had a hard time reading the U-boats' signal traffic. As the number of U-boats in the mid-ocean began to rise sharply, the crisis of the Atlantic war commenced.

The final confrontation began in the fall of 1942 with a series of battles that inflicted a tactical defeat on the Canadian Navy and drove its forces from the central Atlantic. Although only 30 percent of transatlantic convoys between July and the end of 1942 were Canadian escorted, virtually all of them were slow, and they suffered 80 percent of Allied losses in the mid-ocean over the period. The British were quick to blame Canadian incompetence, but without good radar and Huff/Duff to provide solid tactical intelligence, the RCN fought blindly.

Innovative attempts to overcome this problem, such as firing pre-emptive illumination rounds in an effort to catch the U-boats just before they attacked, were dismissed as crude and dangerous. In contrast, fast convoys escorted by well-equipped British ships fared much better. New HF/DF sets in their destroyers picked up shadowers' reports on the ground wave, allowing destroyers to force them below the surface and break contact. Meanwhile, British 10-cm radar established a solid barrier around their convoys at night. Armed with good kit and good tactical intelligence, the British broke up packs, pushed the U-boats back, and sank them.

After a particularly terrible Canadian battle around Convoy SC 106 in November in which 15 ships were lost, the British moved in early December to begin withdrawing the Canadians and the last remaining American escort group from the transatlantic convoys. Although A3's record was not as bad as that of the four Canadian Navy groups in the central Atlantic, its equipment was little better and its Secretary-class cutters were too slow. There were other reasons.

The British had never really been happy about giving the Americans command of half of the transatlantic route in late 1941 nor about leaving the Canadians under U.S. operational control. Moreover, by late November British eastern Atlantic convoys had been suspended to accommodate the Allied landings in North Africa. Britain was now down to one embattled link with the world, which passed through a mid-ocean rapidly filling with U-boats. Not surprisingly, the British moved to take charge. By January the Canadians were on their way out, A3 was slated to leave in due course, and the main burden along the key transatlantic route fell to the British.

When in early 1943, the Royal Navy assumed primary responsibility for the embattled North Atlantic convoys, mid-ocean was the only place left where the Germans could use their large fleet of Type VII U-boats with impunity and the Kriegsmarine could now hope to achieve some kind of strategic or operational victory. By early 1943, roughly 100 U-boats prowled the central-Atlantic gap that was beyond the range of conventional Allied land-based airpower. It proved impossible for convoys to avoid all of them. In January and February 1943, with improved access to the U-boats' operational codes, the Allies tried. But as the Canadians had learned the previous fall, slow convoys beset by packs of 20 to 30 U-boats beyond the range of friendly airpower were bound to suffer. In one of the hardest fought convoy battles, SC 118 lost 11 ships in January, while its Royal Navy escort sank four U-boats.

On 20 February in the gap, U-boats directed by superb intelligence intercepted the westbound slow convoy ONS 166. It was escorted by A3, composed the U.S. cutters Spencer (WPG-36) and Campbell (WPG-32); the Canadian corvettes Rosthern, Trillium, Dauphin, and Chilliwack; the British corvette Dianthus; and the Polish destroyer Burza. The first U-boat to make contact was driven off by a Huff/Duff-directed sweep, and the next day a VLR Liberator from the RAF's 120 Squadron sank a shadower. However, as the convoy reached the depth of the air gap the battle intensified, and on the night of the 21st attacks penetrated the escort screen. The Campbell sank a U-boat, but poor weather and waves of attackers made effective defense of ONS 166 all but impossible. Specially adapted Canadian PBY Catalinas with a virtual VLR capability arrived on 24 February to blunt the assault, driving off most of the shadowers and damaging two U-boats. But the battle spilled onto the fog shrouded Grand Banks and lasted two more grim days. When it was all over, ONS 166 had lost 14 ships.

The inability of even strong and heavily reinforced escorts to drive convoys safely across the mid-Atlantic was demonstrated even more graphically in a series of convoy battles during the third week of March. The Allies had used the U-boats' weather codes as the key to break the daily settings of German operational signals. But when a new code was introduced, Allied special intelligence faltered and convoy routing suddenly lacked the precision necessary to avoid the huge packs lurking in the middle of the ocean. In the first three weeks of March all transatlantic convoys were intercepted, half were attacked, and 22 percent of shipping in those convoys was sunk.

The pinnacle of German success was reached between 16 and 20 March during the battles for convoys SC 122 and HX 229. Forty U-boats were sent to attack them, the largest single Wolf Pack operation of the war. Over the course of four days they sank 21 ships despite the Allies' best efforts to reinforce and economize on the escort by combining the two convoys at sea. Only hurricane-force winds saved the next series of March convoys from serious attack. By the time the month was over, 71 Allied ships, including stragglers, had been sunk in the central Atlantic.

The Tide of Battle Turns

At the end of March, however, everything changed. The Allies agreed to return operation control of the North Atlantic convoys east of 47 degrees to the British, giving a single operational authority effective control over battles in the mid-ocean starting on 30 April. They also agreed to reinforce the North Atlantic with more VLR aircraft and to commit long-awaited escort carriers to eliminate the air gap. Support groups were established to provide powerful and timely reinforcement of the surface escorts, and Allied cryptanalysts once again broke the German operational codes. The latter restored effective routing. It also revealed that morale in the U-boat fleet was poor and ripe for crushing. Finally—and equally important—the weather moderated. As winter storms abated, Allied radar- and Huff/Duff-directed sweeps by destroyers were more successful. As all of these elements came together, British routing authorities began to choose their battles, steering some convoys wide of trouble while heavily reinforcing others and driving them deliberately at waiting U-boats. It was finally time to kill the Wolf Packs.

The strategy worked. In late April the mystique of the Wolf Pack was finally broken in the battle around ONS 5, a 46-ship westbound convoy under British escort. The first U-boats to gain contact were driven off south of Iceland by a U.S. Navy Catalina from VP-84 on 28 April and surface reinforcements. As ONS 5 shook off its pursuers, it needed all the help it could get, for a lapse in Ultra intelligence in late April meant that convoy routing was briefly a mixture of skill and educated guesswork. Meanwhile, German naval intelligence, which was reading the Allied convoy codes, was excellent and two packs totalling at least 40 U-boats were moved into position ahead of ONS 5. Aircraft from Iceland and Newfoundland provided intermittent support around the convoy through late April and the first days of May, while aircraft from Newfoundland attacked the packs in its path farther west, sinking one U-boat. Four destroyers of the British 3rd Support Group joined briefly on the 2nd and 3rd, before they had to leave to refuel.

Skillful routing and the efforts of airmen operating at long range in dreadful weather, however, were not enough to prevent the U-boats from regaining contact with ONS 5 on 4 May. With the escort now much reduced, six ships were sunk that night and four more the next day in submerged attacks delivered in poor weather. That same weather kept air support from finding the convoy during the day on the 5th, and as night fell 15 U-boats remained in contact with a convoy now guarded by only seven escorts.

But those seven, reinforced by the British 1st Escort Group in the early hours of 6 May, were enough. At dusk on 5 May ONS 5 steamed into a Grand Banks fog on a glassy sea—ideal conditions for the escort's 10-cm radar. While U-boats groped around trying to find targets, the surface ships hunted and killed them. By sunrise the next morning the warships had sunk five U-boats. Two others had collided and sunk trying to find the convoy, bringing the German losses to seven in one night of frantic action. Donitz called off the battle.

The carnage among U-boats continued through May, as the Allies abandoned evasive routing entirely and inflicted a crushing defeat on the U-boats. A massive Allied air assault on U-boat transit routes in the Bay of Biscay was matched by success around convoys in the mid-Atlantic, where 50 VLR aircraft now prowled. In May alone Allied forces sank 41 U-boats, while only seven ships were lost from convoys in the North Atlantic. On 24 May Admiral Donitz admitted defeat and called off his packs. For all intents and purposes, the Battle of the Atlantic was over. As shipping losses plummeted in 1943, new construction surged; 14 million tons were completed that year alone.

Through the summer of 1943 the U-boat fleet attempted to maintain a presence in the southern portion of the North Atlantic, from the Caribbean across to North Africa, and to expand their operations through the use of tanker U-boats. U.S. Navy hunter-killer groups, which included escort carriers and were directed by intelligence gleaned from Enigma decryptions, tracked, hounded, and killed them, while the Allied air offensive in the Bay of Biscay exacted a punishing toll. The Kriegsmarine's attempt to renew the mid-ocean offensive in September by fitting U-boats with heavier antiaircraft armament and new acoustic-homing torpedoes ended in utter failure.

By the end of 1943 U-boats were living a fugitive existence in the Atlantic, operating independently and trying not to reveal their presence by transiting radio signals. With that, the U-boats were forced to operate like true submarines, a process which characterized the final 18 months of the war. However, they were never again a threat to Allied strategy.

1. Patrick Abbazia, Mr Roosevelt's Navy: The Private War of the US Atlantic Fleet, 1939-1942 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975).

2. Eric J. Grove, ed., Defeat of the Enemy Attack on Shipping 1939-1945 (Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing for The Naval Records Society, 1997).

3. W. A. B. Douglas et al, No Higher Purpose: The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War, 1939-1945, vol. II, pt. I (St Catharines, Canada: Vanwell Publishing, 2003).

4. W. A. B. Douglas et al, The Creation of a National Air Force: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, vol. II (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986).

5. Michael Gannon, Operation Drumbeat: The Dramatic True Story of Germany's First U-boat Attacks along America's East Coast in 1942 (New York: Harper Collins, 1990).

6. Arnold Hague, The Allied Convoy System 1939-1945 (Vanwell: St Catharine's, Ontario, 2000).

7. Homer H. Hickham, Torpedo Junction: The U-Boat War off America's East Coast (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989).

8. F. H. Hinsley, British Intelligence in the Second World War, abridged edition (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

9. Montgomery C. Meigs, Slide Rules and Submarines: American Scientists and Subsurface Warfare in World War II (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1990).

10. Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run: The Royal Canadian Navy and the Battle for the Convoys (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985).

11. Marc Milner, The U-Boat Hunters: The Royal Canadian Navy and the Offensive Against Germany's Submarines (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994).

12. Ministry of Defence (Navy), The U-Boat War in the Atlantic 1939-1945 (London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1989).

13. Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. I, The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939-May 1943 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1954).

14. Alfred Price, Aircraft versus Submarine: The Evolution of the Anti-submarine Aircraft 1912-1972 (London: William Kimber, 1973).

15. J. Rohwer and G. Hummelchen, Chronology of the War at Sea 1939-1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992).

16. CAPT S. W. Roskill, The War at Sea, 3 vols. (London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1954-61).

17. William T. Y'Blood, Hunter-Killer: U.S. Escort Carriers in the Battle of the Atlantic (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983.