The Battle of Midway rightly stands as the most important naval battle of the Pacific war. In the course of a single day, 4 June 1942, the U.S. Navy sank Japan’s four finest aircraft carriers while losing only one of their own. In the process, Japan’s ability to take offensive actions in the wider war it had initiated on 7 December 1941 was permanently impaired. By contrast, the Americans were given a respite from a string of early-war defeats, and were free to contemplate offensive actions of its own. The result was the opening of the Guadalcanal campaign a mere two months later, which would engulf the Solomon Islands and New Britain in conflict for the next year and a half.

It would stand to reason that a battle as momentous as Midway—and a defeat as calamitous as the one the Japanese suffered—would have led to a major re-evaluation of their naval practices and, most likely, to lessons learned that would have improved Japanese performance in future battles. Learning can take place on a number of levels, and the effects of Midway were felt across the board, from the halls of power down to the level of the navy’s operational personnel.

The Carrier Above All

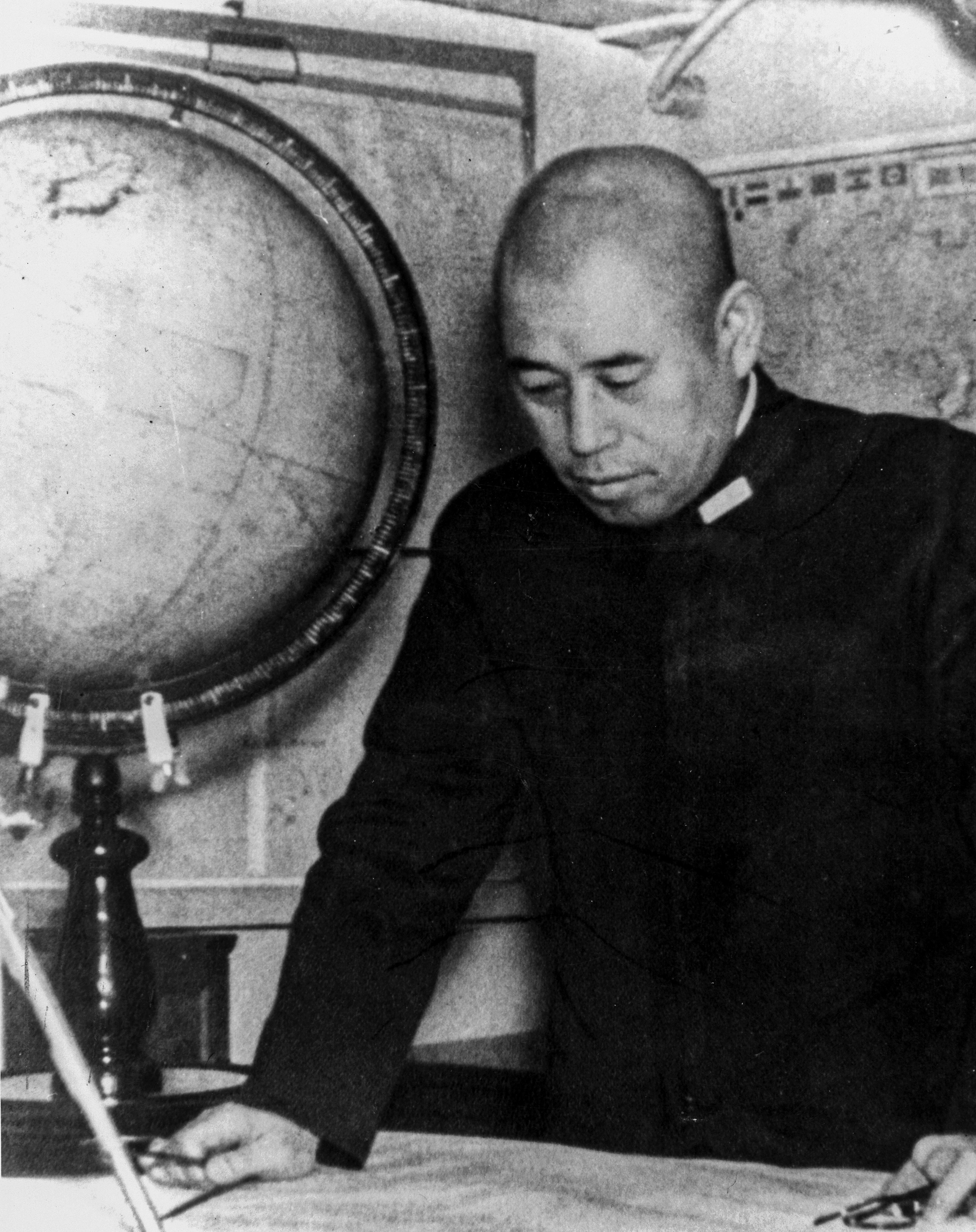

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, the Imperial Japanese Navy lost no time in trying to reconstitute its naval aviation arm. Part of this process was the re-establishment of the carrier fleet’s staff, and undertaking a lessons-learned project. On 15 June, just one day after the defeated fleet limped back into Hashirajima anchorage, near Hiroshima, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s staff on board the light cruiser Nagara was transferred to the battleship Kirishima. This would be their interim home as the carrier fleet struggled to reinvent itself.1 Shortly thereafter, the fleet’s carrier arm—First Air Fleet, which had in essence been destroyed during the battle—was formally disbanded and renamed Third Fleet. Nagumo’s staff thereafter began crafting a new carrier doctrine for the imperial navy that was intended to incorporate the lessons the battle had taught.

Third Fleet’s doctrine emerged in late July 1942. It contained a number of important recognitions and tactical innovations.2 Most important, for the first time, the navy explicitly recognized the primacy of the aircraft carrier, noting that it was “the center, the main objective, of the Decisive Air Battle” and that “[all other] surface forces will cooperate with them.” The battleship was thus finally and formally removed from the apex of Japanese naval thinking.

There are multiple levels of irony here. The original battle plan for Midway, crafted by Combined Fleet Commander-in-Chief Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, had anticipated that the Japanese Navy’s battleship formations would have the final word with the American fleet that sallied forth to defend the atoll. While Japan’s carriers were to weaken U.S. forces as they approached, it was planned that the culmination of the battle would have been a large surface action. Of course, nothing of the sort transpired. After Japan’s main carriers had been destroyed, Admiral Yamamoto declined to press the battle further, despite his own powerful battleship force having been completely undamaged thus far during the fight. The other irony of this situation, of course, was that Yamamoto had built his career and reputation as an outspoken advocate of air power and had often been openly scornful of the battleship’s primacy. Yet his battle plan called for the extensive use of battlewagons and then, in defeat, had rapidly led to their formal dismissal from a primary strategic role.

New Carrier Defense

The Japanese understood that their carrier force suffered from a number of shortcomings during the battle. One of the foremost areas of failure was that of fleet air defense. The fact that the Americans had caught three Japanese carriers flat-footed during the morning of 4 June, and another almost equally unaware during that afternoon, spoke volumes about the imperial navy’s ability to protect itself from any concerted air attack. Third Fleet worked to remedy these shortcomings in its new doctrine.

The first major change proposed was to the fleet’s formation. Carrier divisions, which formerly had been composed of two carriers, were now to contain three flight decks—two fleet carriers and a light fleet carrier, with the smallest ship charged primarily with carrying combat air patrol fighters. More important, the carrier divisions were to be widely separated from each other to prevent the overconcentration of these precious assets that was perceived to have been one of the causes of the disaster at Midway. The Japanese would now accept the penalties in offensive coordination accruing from dispersal in favor of the lesser likelihood of losing an entire carrier force at a single blow.

The carrier divisions were to be preceded by a scouting line of cruisers and battleships that would position themselves ahead of the advancing carrier fleet by a distance of between 100 to 200 miles. These heavy units would be spread out from each other at roughly the limits of visual range. Their presence ahead of the carrier formation was designed to achieve several objectives. First, it placed the primary scouting aircraft of the fleet (the battleship and cruiser floatplanes) that much closer to the prospective enemy, aiding in its location. It was felt that returning floatplanes would also have a better chance of locating friendly forces. More important, the scouting line would hopefully provide better raid warning for the carriers trailing behind. Not surprisingly, the skippers of the scouting vessels also believed that an unwritten portion of the new doctrine envisioned their vessels acting as bomb sumps for the carriers, and, as a result, it was not universally popular.

The most intriguing thing about this formation is it betrays the lack of understanding about the usefulness of radar. While the Japanese were experimenting with radar at this point (the first test sets having been installed on board battleships just prior to the battle) and saw its value both as a gunnery tool and for simple air raid warning, they never made substantial progress toward using it as a tool for coordinating fleet air defenses. Whereas the Americans had begun making progress toward coordinating all of the information available to a fleet (radar, radio intercepts, and visual sightings from its own aircraft) in a centralized facility (called the Combat Information Center, or CIC) and using that data to vector defensive fighters against incoming targets, the Japanese never made this same leap. The proposed Third Fleet scouting line doctrine was essentially a poor man’s substitute for a modern air defense system. Japanese task forces would not advance appreciably beyond this level of sophistication for the remainder of the war.

On Board Changes

The Japanese Navy implemented additional changes as well. Damage control—the techniques for keeping a ship afloat, extinguishing its fires, and recovering from other damage inflicted during battle—was given greater emphasis in the navy’s training.3 All four of the Japanese carriers lost during the battle had succumbed to devastating fires fueled by the ships’ own aviation gasoline stores, as well as aviation ordnance strewn about the hangar decks. The navy took pains to improve its capabilities in these areas. It also began performing more of its operations on the flight deck. Where ordnance arming and refueling had been accomplished primarily in a carrier’s enclosed hangars, now more of it was conducted on the flight deck, where aircraft and ordnance could be more easily disposed of in case of an emergency.

The battle had also shown that fighters were the most important air assets on board the carriers, as they were required not only for accompanying strike operations but also for defending the fleet. As a result, the composition of carrier air groups was changed. Where the typical Japanese fleet carrier, pre-Midway, carried a squadron of fighters, dive-bombers, and attack planes with 18 aircraft in each for a total of 54 operational aircraft, the new carrier air groups on board the Shokaku and Zuikaku would be composed of 27 fighters, 27 dive bombers, and 18 torpedo planes. Light fleet carriers such as the Zuiho would carry 21 fighters and just 6 torpedo aircraft.4

Finally, the battle demonstrated that the easy days and accordingly low attrition rates of the first part of the war were over. Modern naval warfare consumed planes and aviators at a frightening pace, and the Japanese accelerated their aviator training programs to meet these new demands.5 The number of naval aviators graduated in 1941 had vastly eclipsed prewar rates, and the Japanese moved to further increase this pipeline by increasing the size of the candidate pool and lowering the selectivity and dropout rate of the ensuing flight-training programs. In this manner, the Japanese were able to field enough new aviators to fill their billets throughout 1942, and indeed for the remainder of the conflict.

All to No Avail

Yet despite these honest attempts to come to grips with the lessons of the battle, none of these innovations would have any serious impact on Japan’s naval efforts, or the outcome of the Pacific war. The simple fact was that the Japanese were so far behind on many of these issues that their efforts at playing catch-up would be mitigated by American initiative, as well as the oncoming wave of U.S. material superiority. Tactical make-dos, such as Third Fleet’s scouting line, could never be an adequate replacement for a fleet air defense centered on the use of radar, the CIC, and good fighter vectoring. Likewise, Japan’s belated acceleration of its aviator training programs would fill its rosters with youngsters who were ill-trained and underprepared for the rigors they would face in combat. Once the final cadres of Japan’s elite prewar squadrons were destroyed in the meat grinder of the Solomons in late 1942, the country’s overall level of aviator proficiency would begin a steep decline.

The most important factor in the failure of these initiatives, of course, was a simple lack of war materiel compared to the Americans. Japanese shipyards would not replace the four lost Midway carriers on a unit-for-unit basis until early 1945, by which time the U.S. Navy had commissioned a dozen of its own Essex-class fleet carriers, and dozens more light fleet and escort carriers. Likewise, Japanese aircraft production began to be dwarfed by early 1943 by the prodigious output of America’s factories, which would produce five times as many aircraft as Japan that year. Tactical and doctrinal band-aids such as the Japanese could contrive could not compensate for the vast disparities in productive power between the two combatants.

Covering Up Bad News

If the eventual picture was bad in those areas where the Japanese had made an honest effort, it was even worse at the levels of national and naval strategy, where Japan’s reaction to the Battle of Midway was marked by delusion and deceit. Indeed, the loss of Midway marked the inception of a persistent campaign by the Japanese Navy, and the nation’s leadership as a whole, to hide or disguise bad news.

Even before Yamamoto’s defeated fleet made port at Hashirajima on 14 June, the navy, in concert with Emperor Hirohito, was concocting ways to cover up the entire affair.6 To the public, the navy announced that Midway had been another smashing victory, with two American carriers sunk. Only later was it added, almost as an aside, that two Japanese carriers—the Kaga and Soryu—had also been sunk. The navy abetted this subterfuge by officially keeping the sunken Akagi and Hiryu on the navy’s roster, but listing them as “unmanned.” To support this illusion, wounded sailors from the battle were kept in separate hospitals and denied visits with families. The bulk of the unwounded were shortly transferred to other commands fighting in the southwest Pacific, where they would be as far away from the temptation to reveal their knowledge as possible. Many of them would subsequently die in these remote theaters of action. The emperor was so pleased by these efforts at cover-up that he even briefly floated the notion of issuing an official imperial rescript to commemorate the battle, but he was finally dissuaded by his courtiers.

This reaction to a national defeat would set the pattern for an ongoing wholesale government manipulation of the Japanese media to cover up what would shortly become a ceaseless drumbeat of bad news from the various war fronts. Thus, by late 1944, when the war situation had deteriorated to the point where every Japanese citizen was directly exposed to the rigors of attack by B-29s—which even the simpleminded should have realized could only have occurred as a result of Japan’s ongoing defeats—the media continued pumping out an unrelenting stream of government-inspired phantasmagoria that proclaimed fresh victories.

Business as Usual for the Navy

Within the upper ranks of the navy itself, where the evidence of the disaster could not be so easily erased, there was similarly little effort to divine the true meaning of Midway. It is striking that in the immediate aftermath of such a calamitous battle, no heads rolled among the top brass of the navy. Neither Admirals Yamamoto nor Nagumo was replaced. Nor was there any apparent effort on the part of naval general headquarters, which had fiercely opposed Yamamoto’s battle plan, to exert its authority over the Combined Fleet or undertake a wholesale housecleaning there. Indeed, business remained pretty much as usual. The diary of Admiral Ugaki Matome, for example, which provides rare insight into the inner workings of the imperial fleet’s upper echelons, betrays no hint of self-doubt that the outcome of Midway might somehow implicate the navy’s fundamental views of naval strategy.

This is quite ironic, given the navy’s prewar doctrine. From the end of World War I, Japan’s fleet had envisioned an eventual contest with the U.S. Navy that would hinge on the outcome of a single decisive battle. It was an article of faith within the Imperial Japanese Navy that a single such climatic effort would determine the outcome of the war. Indeed, it was hoped that when the United States was defeated at Midway, it would be induced to negotiate a peace settlement. Yet when presented with its own defeat in just such a battle, the top navy brass refused to accept the verdict of its own doctrine. Indeed, it would spend the remainder of the war in search of other decisive battles that would somehow magically render moot the remorseless attritional verdict that the U.S. military began imposing on the conflict.

Similarly, Japanese operational art appears to have remained essentially unchanged for the remainder of the war. An example is the continued usage of dispersed battle formations. During Midway, the Japanese had distributed their warships in a number of widely separated formations. The underlying intent was to deceive the Americans as to Japanese intentions and strength for the upcoming battle, and thereby lure them to their doom. In the end, though, dispersal had led to Admiral Nagumo’s carriers being inadequately backed by Yamamoto’s battleship-heavy Main Body and other support formations when Nagumo’s force was ambushed. Yet this same love of dispersal and deception manifested itself in the subsequent carrier battles in the Solomons, as well as the action at Leyte Gulf in late 1944.

In the final analysis, it seems clear that at a fundamental level the Japanese warrior caste could not learn, could never even admit that it was beaten. Nor would it acknowledge even to itself the defects of national policy that had brought it to ruin. Electing to engage in a war with the United States was the height of strategic folly. That this misguided initial decision was followed by a string of strategic errors and poor thinking on the part of Japan’s military leaders seems hardly surprising. In the end, Midway stands as the first truly stark warning that Japan’s militaristic national strategy was bankrupt. And yet, unable or unwilling to learn from the evidence laid before it, the navy brass would exert every effort to continue dragging Japan through another three years of increasingly horrific and ultimately pointless savagery.

1. Jonathan Parshall, and Anthony Tully. Shattered Sword: the Untold Story of the Battle of Midway, (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2006), p. 386.

2. We draw extensively from Senshi Sosho, Vol. 49, Nantohomen Kaigun Sakusen, 1 Gato Dakkai Sakusen Kaishimade. (Southwest Area Naval Operations, 1, To the Beginning of Operations to Recapture Guadalcanal), a section of which was translated by RAdm Edwin T. Layton, U.S. Navy (Retired).

3. Naval Technical Mission to Japan S-84 (Report on Japanese Damage Control), p.7.

4. Mark Peattie. Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909-1941, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001), p. 338.

5. Shattered Sword, p. 390.

6. Shattered Sword, pp. 386-88.