Before leaving Pearl Harbor, I was given very brief indications that we expected an attack and there was obviously a big battle coming up in the middle of the Pacific. That’s about all I was told before I landed aboard the Yorktown (CV-5) on May 30. That night, the air group met in the wardroom where Commander Murr Arnold, the air officer, gave us a complete briefing on everything they knew about the opposing Japanese forces and their probable intentions. So we had a day or so to think before we arrived in position. After this briefing, it was obvious a very serious and crucial engagement was coming up. If we could win this one, we might be able to stop the Japanese advance.

Lieutenant Commander Maxwell Leslie, commanding officer of the Yorktown’s dive-bomber squadron who was going to lead VB-3 and part of VS-5, and Lieutenant Commander Lance “Lem” Massey, commanding officer of Torpedo Squadron (VT) –3, suggested that we have a conference. I’d talked a bit to Lem before that and told him I thought the fighter escort should go with him instead of with the dive bombers. He said, “I think you ought to get up with the dive bombers because that’s where the Zeros are going to be. That’s where they were in the Coral Sea battle.” We knew we weren’t going to have enough fighters to send with each.

I had a plan to take eight planes because I wanted two divisions—that was the basic tactical breakdown we developed—and I couldn’t believe that anybody would try to break this up. If you’re going to send any number of airplanes, it’s got to be divisible by four, otherwise you’ve left two planes without wingmen.

Max Leslie said he thought that I should go with the torpedo planes. I said, “How about letting me decide?” because they were playing Alphonse and Gaston, trying to give the fighters to the other squadron.1 I decided that, since in the Coral Sea battle the torpedo planes had gotten in pretty much unopposed and done the work in sinking these ships, the Japanese would be more concerned about them. They were going to be very concerned about a torpedo attack, and they’re going to try to knock it out. So we all agreed that I would go with VT-3.

The torpedo planes were old fire traps that were so slow—those old TBDs would go about 80 knots, with the nose down maybe 110—awkward and had no self-sealing tanks. They needed protection more than anyone else, so that governed our decision.

I don’t know how many people slept very well the night of the 3rd of June.

I was very concerned about whether the torpedo planes could get in or not, and I knew that if the Japanese were together in one formation and had a fighter combat air patrol from all the carriers, we would very likely be outnumbered. We were also quite concerned that the Zero could outperform us in every way. We felt we had one advantage in that we could shoot better and had better guns. But if you don’t get a chance to shoot, better guns matter little. I was thinking about all this and which pilots I would take with me. I didn’t sleep much that night, but we were all pretty optimistic because we felt that we were going to get tactical surprise. We didn’t think the Japanese knew that we were anywhere near there, and this was a great morale builder, when you think you’re going to have one of the basic principles of warfare—surprise—on your side.

I was a little appalled that we were in two separate task forces, with the Yorktown the only carrier in one of them. Captain Elliott Buckmaster, commanding the Yorktown, or Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, tactical commander of all the carriers and commander of Task Force 17, I guess, made the decision the next morning before we launched that we would have only six fighters go. I didn’t have time to work my way up to talk to either one about it, but I did go to Murr Arnold. I said I was appalled that the Yorkton was separated from the Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet

(CV-8), but wasn’t too worried because I thought they would stick close together, enough for mutual defensive support. He said, “And, another thing, you’d better bring your planes back because I think we’re in for one hell of a fight.”

I held a last-minute briefing and emphasized that I wanted the formation to stick together, that nobody was going to be a lone wolf, because lone wolves don’t live very long under the circumstances we were going into, and that was the best way to survive and protect the torpedo planes.

I had to quickly revise the formation that we were going to fly over the torpedo planes because six isn’t divisible by four. I had Ensign Robert A. M. “Ram” Dibb as my wingman with Lieutenant (junior grade) Brainard Macomber, of VF-42, as my other section leader, and his wingman was Ensign Edgar Bassett, also of VF-42. That left two, Machinist Tom Cheek and Ensign Daniel Sheedy.2 So I decided that we would put them just astern of the 12 torpedo planes, down at a slightly lower altitude than I would fly, 1,000 or 1,500 feet above the torpedo plane formation, which would be a formation in the shape of a triangle, a sort of a V of Vs. That’s the way they would fly up to the target until they had to split and spread out to make the torpedo attack.

We had to do S turns, to slow down so we wouldn’t run away from the TBDs because they were so slow, and we didn’t want to be stalling along with no ability to maneuver in case something hit us before we anticipated it. We were flying our standard combat formation that I’d developed, with a section leader and only one wingman, in a combat division of four planes, two two-plane sections. I was leading. Ram Dibb was right in under my wing, and Macomber had Bassett on his wing.

I’d made that standard before the war. I recommended, after I’d developed this weave business, that all the squadrons accept this as a standard fighting formation. I got a message back from commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, that since the two-plane section was such a radical change he wouldn’t force all the squadrons to do it, but that I had authority to do it in my squadron. Actually, by this time the idea was catching on anyway. VF-2 was doing it, and so were some of the others. They’d thrown away the third plane and were flying two-plane sections, but they had not adopted the weaving tactics.

The Hornet was rather new in the Pacific, and I hadn’t seen her pilots, but I tried to circulate this around. Lieutenant Commander James Flatley, executive officer of the Yorktown’s VF-42 at the Battle of the Coral Sea, and I had discussed it—sometimes late into the night—and he helped me for a while. He said: “I think the four-plane division is good, but I think we shouldn’t all try the same thing. Why don’t I try six planes in a formation, and you try four, and we’ll see which one makes out the best.” Later he sent two messages, a personal one to me saying the four-plane division is the only thing that will work, and “I am calling it the Thach Weave, for your information.” Six planes don’t work. The two extra ones get lost. He sent an official message describing this and saying that they were convinced that it was the only way for our fighters to fight, especially against superior enemy fighters.

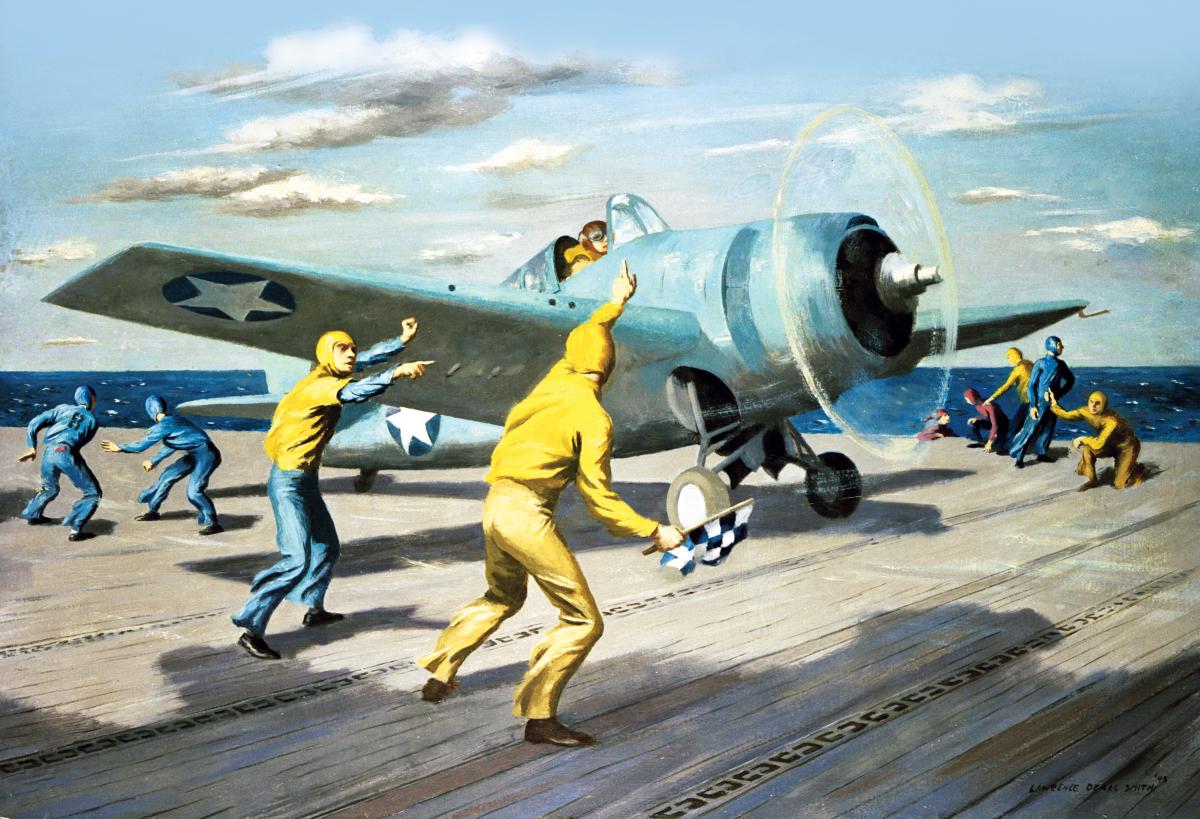

We took off later than the planes from the Enterprise and Hornet. They started a little after 0700 and we didn’t begin launching until around 0840. By 0900 I was in the air. It was a beautiful day. There were little puffy clouds up around 1,000 feet to 1,500 feet that sometimes would get a little thicker and other times they’d open up and be very scattered. It was that way all the way into the enemy formation.

A strange thing happened on the way. We were flying along and, all of a sudden, ahead of us and a bit to the side, two big explosions threw water way up high. There didn’t seem to be anybody around, but I wondered if someone hadn’t inadvertently dropped a couple of bombs. That’s exactly the way it turned out. In arming the bombs—the arming device worked in a way that also released the bomb. Max Leslie and three others in his squadron lost theirs.

So we went in. All of us were, of course, highly excited and admittedly nervous. I think most other people did pretty much what I did—kept going over my check-off list, and as soon as we had gotten in the air I had each section test their guns so they’d be ready, and all the switches on and not on safety, and in we went.

Lem Massey made a small change of course to the right. We took off on a heading of about southwest, and I wondered why he did that. Looking ahead, I could see ships through the breaks in the clouds, and I figured that was it. We had just begun to approach about ten miles from the outer screen of this large force, looked like it was spread over the ocean, and several colored antiaircraft bursts appeared out in our direction, one red and another orange, and then no more. I wondered why they’d be shooting at us because we weren’t even nearly in range. We’d been sighted from the surface screen and they were alerting the combat air patrol. A very short time after, before we got near antiaircraft range, Zero fighters came down on us. I tried to count them. We’d always been trained to count things at a glance, and I figured there were 20.

The first thing that happened was that Bassett’s plane was burning. He pulled out, and I didn’t see him any more. He was shot down right away; I didn’t see the Zero that got him. I was surprised that they put so many Zeros on my six fighters. I had expected they would go for the torpedo planes first. They must have known we didn’t have the quick acceleration to catch them the way they were coming in at high speed in rapid succession and zipping on away. But then I saw they had a second large group that was now streaming in right past us and into the poor torpedo planes.

Macomber’s position was too close to me to permit an effective weave, and I was not getting very good shots at the Zeros. I called him on the radio and said: “Open out more. About double your present distance and weave.” No acknowledgment. His radio must have been dead. (He has since stated it was). How ironic this situation had become! I had spent almost a year developing what I was convinced was the only way to survive against the Zero, and now we couldn’t seem to do it. I kept wondering why Macomber was so close instead of being out in a position to weave. Of course, he had never practiced the weave. He was one of the VF-42 pilots during the Coral Sea battle and had tangled with some Zeros then. But he had reported to VF-3 just before we flew out to land aboard the Yorktown enroute to Midway.

I had assumed that my exec, Lieutenant Commander Donald Lovelace, had briefed them or required them to read the Squadron Tactical Doctrine. I suddenly realized Don didn’t have much time to brief anyone before he had his head chopped off.3 I had tried so hard to wipe that ghastly accident out of my mind that I forgot Don was no longer with us. Then I remembered telling my flight during the last-minute briefing to stick together. Macomber must have thought I meant for him to fly a closed-up formation. What I actually meant was I wanted no lone-wolf tactics.

Too late to correct that misunderstanding now. I couldn’t see Cheek and Sheedy so I called Ram Dibb, my wingman, and said, “Pretend you are a section leader and move out far enough to weave.” He said, “This is Scarlet Two, wilco.” His voice sounded like he was elated to get this “promotion” right in the middle of a battle.

Several Zeros came in on a head-on attack on the torpedo planes and burned Lem Massey’s plane right away. It just exploded in flames. And, beautifully timed, another group came in on the side against the torpedo planes. The air was like a beehive, and I wasn’t sure at that moment that anything would work. It didn’t look like my weave was working, but then it began to work. I got a good shot at two of them and burned them, and one of them had made a pass at my wingman, pulled out to the right, and then came back. We were weaving continuously, and I got a head-on shot at him, and just about the time I saw this guy coming, Ram said, “There’s a Zero on my tail.” The Zero wasn’t directly astern, more like 45 degrees, beginning to follow him around, which gave me the head-on approach.

I probably should have decided to duck under this Zero, but I lost my temper. He just missed me by a few feet with flames coming out of the bottom of his airplane. This is like playing chicken with two automobiles on the highway except we were both shooting as well. That was a little foolhardy. I didn’t try it any more.

They kept coming in and, by this time, we were over the screen, and more torpedo planes were falling, but so were some Zeros. At least we’re keeping a lot of them engaged. We could see the carriers. They were steaming at very high speed and launching airplanes. The torpedo planes had to split in order to make an effective attack. We thought we were doing pretty well until they split. Then, of course, they were extremely vulnerable, all alone with no mutual protection. The Zeros were coming in on us, one after the other, and sometimes simultaneously from above and to the side. We couldn’t stay with the torpedo planes, except for one or two that happened to be under us.

I kept counting the number of airplanes that I knew I’d gotten in flames going down. You couldn’t bother to wait for them to splash, but you could tell if they were flaming real good and you saw something besides smoke. If it was real red flames, you knew he’d had it. I had this little knee pad and would mark down every time I shot one that I knew was gone. This was sort of foolish. Why was I marking my pad when it wasn’t coming back? I was utterly convinced then that we weren’t coming back. There were still so many Zeros, and they’d already gotten one of our fighters, and looking around, I couldn’t see Cheek or Sheedy anymore, so there were just two others that I could see of my own; Macomber over on my left and Ram Dibb, and me.

Pure logic would convince anyone that with their superior performance and the number of Zeros they were throwing into the fight, we could not possibly survive. “Well,” I said, talking to myself, “we’re going to take a lot of them with us if they’re going to get us all.” We kept on working this weave, and it seemed to work better and better. How much time this took, I don’t know, but ever since then I haven’t the slightest idea how many Zeros I shot down. I just can’t remember, and I don’t suppose it makes too much difference. It only shows that I was absolutely convinced that nobody could get out of there, that we weren’t coming back, and neither were any of the torpedo planes.

Then it seemed that the attacks began to slack off a little bit. I called and said: “Hell, they don’t like it as well as they used to. Stick together and we’ll get home yet.” The torpedo planes went on in. I saw three or four of them that got in and made an attack. I believe that at least one torpedo hit was made. All the records, and the Japanese, and Sam Morison’s book said that no torpedoes hit.4 I’m not sure that the people on board a ship that is hit repeatedly really know whether they got hit by a torpedo or a bomb. I was aboard the Saratoga (CV-3) when she was torpedoed and the Yorktown when she was bombed and I couldn’t tell the difference. I think I saw at least one hit, but it occurred either during or very shortly before the dive bombers came in.

Being pretty busy, I couldn’t more than every now and then get a glance. Then I saw this glint in the sun—it looked like a beautiful silver waterfall—these were the dive bombers coming down. I could see them very well, because that’s the direction the Zeros were, too. They were above me but closer, not anywhere near the altitude of the dive bombers.

I’d never seen such superb dive bombing. It looked to me like almost every bomb hit. Of course, there were some very near misses. There weren’t any wild ones. Explosions were occurring in the carriers, and about that time the Zeros slacked off. We brought out two torpedo planes and then went back and picked up another one we saw, stay right with him and over him, hoping that the Zeros wouldn’t have him all to themselves. Of course, the TBDs may have been badly hit and some of them were in the water and we didn’t see them after the torpedo attack. I know more than two attacked. We had come in a little earlier than the dive bombers by a matter of just minutes, and drew most, if not all, of the enemy combat air patrol. They were ready and waiting for us as we came in a full 30 minutes after the VT-8 and VT-6 attacks.

I could only see three carriers. I never did see a fourth one. One of them, probably either the Soryu or the Kaga, was burning with bright pink and sometimes blue flames. I remember looking at the height of the flames noticing that it was about the height that the ship was long—the length of the ship—just solid flame going up and a lot of smoke on top of that. I saw three carriers burning pretty furiously before I left, picked up one torpedo plane, and flew on back toward the Yorktown with it. I was over the Japanese fleet a full 20 minutes.

Was the decision to cover the torpedo planes the right one? Oh, yes. These torpedo pilots were all my very close friends, Lem Massey especially, and he was lost. I felt pretty bad about that, just sort of hopeless. I felt we hadn’t done enough, that if they didn’t get any hits this whole business of torpedo planes going in at all was a mistake. But, of course, you couldn’t fail to send them, and in thinking about it since then I realize that this classic, coordinated attack that we practiced for many years, with the torpedo planes going in low and the dive bombers coming in high, pretty much simultaneously, that’s what we tried to do, although it’s usually better if the dive bombers hit first, then the torpedo planes can get in better among the confusion of bombs bursting.

I realized that here was the reverse of the Coral Sea battle, that these people hadn’t given their lives in vain, they’d done a magnificent job of attracting all the enemy combat air patrol, all the protection that the Japanese carriers had were engaged and were held down. So we did do something, and maybe far more than we thought at the time. We engaged the enemy that might have gotten into the dive bombers and prevented them from getting many hits.

The six Yorktown Wildcats were the only fighters that got any combat over the Japanese fleet—no other fighters. And VF-3 was the only fighter squadron in the Battle of Midway that had any significant aerial combat later in defense of our carriers.

Working the Weave

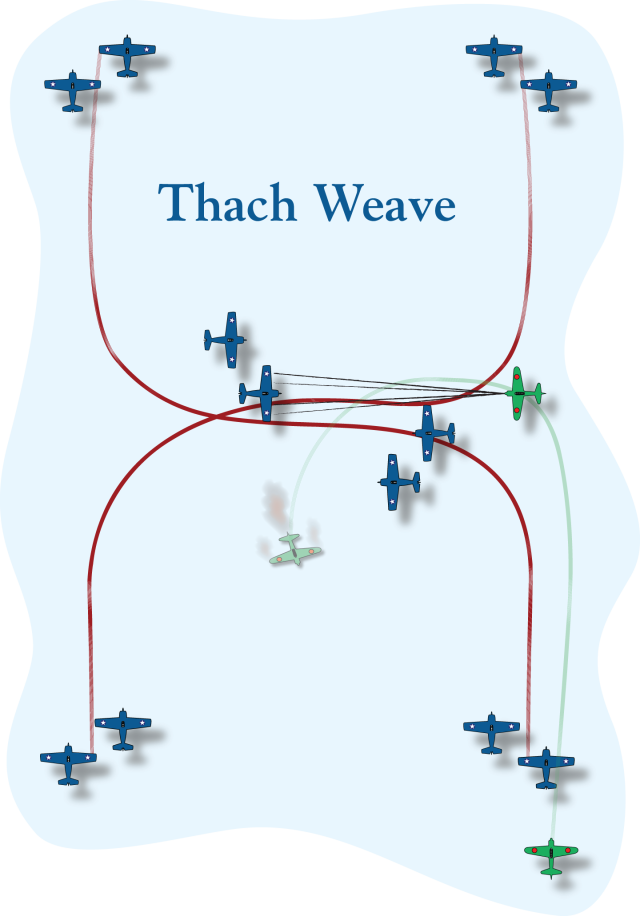

Perhaps the best-known aerial dogfighting tactic to emerge from World War II was the “Thach Weave.” Developed by Lieutenant John S. “Jimmie” Thach, the maneuver helped Grumman F4F Wildcat pilots survive against much faster, quicker climbing, and tighter turning Mitsubishi A6M Zeros in the early days of the war. First put into practice during the Battle of Midway, the weave was born not of battle, but of an anonymous report. As Thach recalled:

I developed the “weave” before the war, in the summer of 1941 on my kitchen table in Coronado. I’ve read that I studied the combat reports of the Coral Sea battle and figured it out just before the Battle of Midway. This is not true at all. We’d been practicing it for a long time.

In the spring 1941 we received an intelligence report of great significance out of China. It described a new Japanese aircraft, a fighter, that had performance that was far superior to anything we had. It had more than 5,000-feet-per-minute climb, very high speed, and could turn inside of any other aircraft. I felt we should give the report some credence because whoever wrote it talked like a fighter pilot, like he knew what he was talking about.

If you have somebody who’s faster than you are, you have to trap him somehow so that he can’t use his superiority, whatever it is. I believed we had one advantage: We had good guns, and could shoot and hit. We must do something to entice the opponent into giving us that one all-important opportunity. It was the only chance we had. So every night I worked on this problem. I used a box of kitchen matches on the table and let each represent an airplane. I would work on this every night until about midnight.

For years the formation we flew with, three-plane sections, a leader and two wingmen, irked me. If you’re going to fight and do radical turns, this was an unwieldy formation. It was obvious that if we were going to be able to do something sudden to fool an enemy, we ought to throw away one of those planes and just have a two-plane section, which is what I did. At that time, everybody was flying three-plane sections, both in our country and Europe.

Thach envisioned the basic combat unit as a four-plane division consisting of two two-plane sections. The right pair would watch the tails of the left section and vice versa. With the two sections split wide apart, an enemy plane would have to choose one over the other. If the right section saw its fellows about to be attacked, it would break into a 90º turn toward the left section. That section, always watching to the right, would see the break and instinctively know they were under attack and immediately break to the right. The enemy would follow the left section, but be subject to a head-on attack by the right section.

So, the weave looked like it was, maybe, the only thing to do. I was very excited about this discovery and presented it to the squadron. To simulate the Zero’s superiority I told Butch O’Hare, one of the squadron’s top pilots, to take four aircraft and use full power, and I would take four and never advance the throttle more than half way. That gave him at least superior performance. Maybe double, maybe not. I told Butch, “You attack from any direction you want.”

He made all sorts of attacks, quite a few from overhead and coming down, this way and that.

After we landed he said: “Skipper, it really worked. It really works. I couldn’t make any attack without seeing the nose of one of your half-throttle airplanes pointed at me. So at least you’re getting a shot, even though I might also have got a shot, at least it isn’t one sided. Most of the time that sudden turn, although I knew what you were going to do, it always caught me a little bit by surprise. When I was committed and about to squeeze the trigger, here he went and turned and I didn’t think he saw me.”

Of course, he didn’t. That’s the beauty of this, and you didn’t need a radio. So we felt a little better about the situation. Now we had something to work on, to keep us from being demoralized.

Jimmy Flatley, gave it the name “Thach Weave.” I didn’t.

1. Alphonse and Gaston were a pair of comic strip characters who first appeared in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal on 22 September 1901. Their “After you, Alphonse” and “No, you first, my dear Gaston!” routine ran for more than a decade.

2. VF-3 had been assigned to the Saratoga (CV-3). When it was reassigned to the Yorktown, the squadron acquired 16 combat-seasoned pilots from that carrier’s VF-42.

3. Lovelace was killed on 30 May 1942 when VF-3 first landed aboard the Yorktown. After he parked forward of the landing barrier, his wingman, Ens Robert C. Evans, missed the arresting wires, and bounced over the barrier onto the back of Lovelace’s aircraft. While Thach stated in his oral history that Lovelace was decapitated, historian John Lundstrom wrote that he suffered a fractured skull and severed carotid artery. Lundstrom, John B., The First Team (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1984) p. 319.

4. Morison, RAdm Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1954) Volume 4.