The gathering on the Charlestown waterfront is no ordinary birthday party. For one thing, the guest of honor is turning 208, and she has been decked out with signal flags to mark the occasion. Along with cake, the refreshments include a wooden cask containing a steaming modern version of grog, a mix of rum, water, citrus juices, and spices.

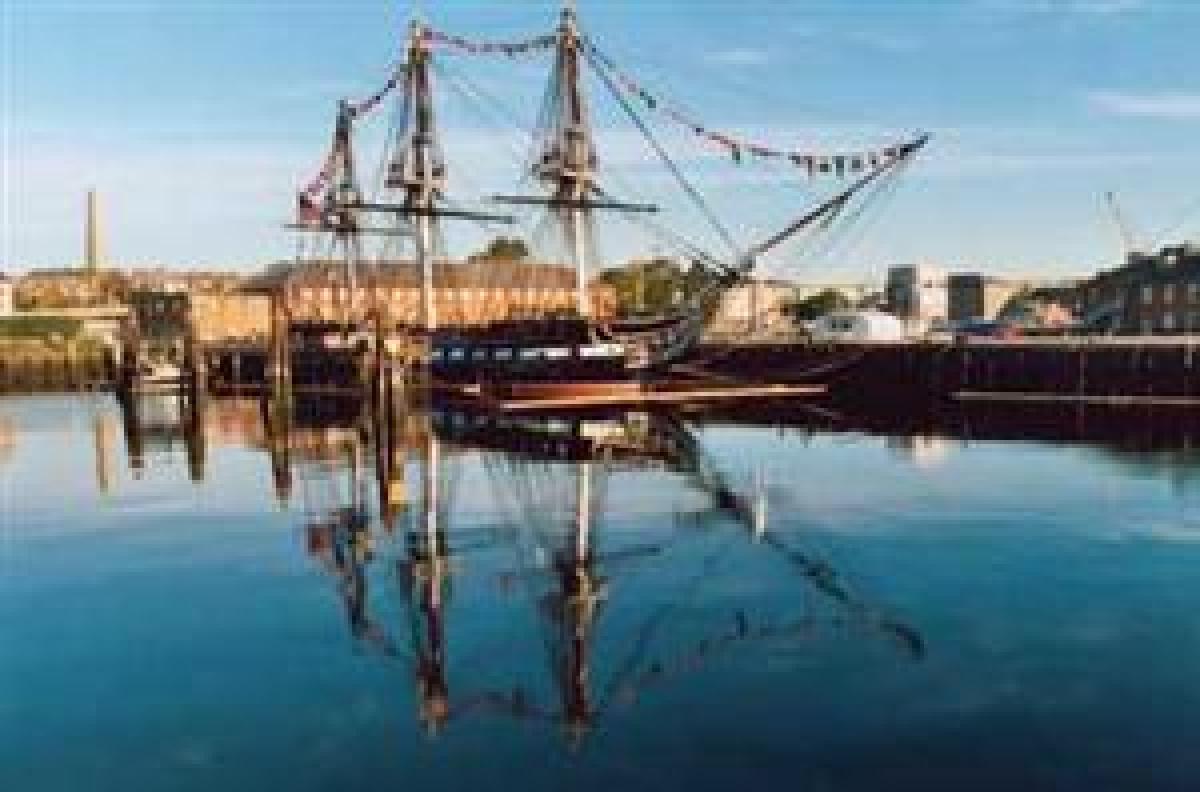

The party is for the frigate USS Constitution, the oldest commissioned warship afloat in the world. She was launched in Boston on 21 October 1797, and now makes her home at the former navy yard in Charlestown, Massachusetts, just across the mouth of the Charles River from the spot where she first slipped down the ways.

She is surrounded by history. Her bowsprit points toward the spire of Boston's Old North Church, the elevation from which lanterns informed Paul Revere of Redcoat intentions in April 1775. The Constitution's stern faces the spot where Revere landed in Charlestown at the start of his famous ride. The Bunker Hill monument overlooks the yard from the center of Charlestown, commemorating the major battle of the Revolutionary War.

The navy yard is almost as old as the Constitution. Established in 1800, it had expanded into a sprawling complex of 130 acres before it closed in 1974. Today a 30-acre core remains as part of Boston National Historical Park, run by the National Park Service. It is one stop on Boston's Freedom Trail.

Over the centuries, Charlestown Navy Yard (later renamed the Boston Navy Yard and then the Boston Naval Shipyard) played a vital role in the development of the U.S. Navy. The first ship built here, the USS Independence, was launched in 1814. Rated at 74 guns, she was the nation's first ship of the line. The USS Hartford, Admiral David Farragut's flagship during the Civil War, was launched here in 1858. Two more of the yard's ships entered the history books when they clashed, however briefly, during the Civil War. The frigate Cumberland, launched in 1842 and originally mounting 50 guns, was destroyed by the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia in an encounter that forever changed the world's navies. The pioneering ironclad had been built atop the burned and scuttled hull of the USS Merrimack, which entered service as a screw frigate launched at Charlestown in 1855.

During World War II, the yard reached its peak of activity, building 14 Fletcher (DD-445) -class destroyers. One example of the type, although she was not built here, is the Cassin Young (DD-793), a combat-tested veteran open to the public a stone's throw from the Constitution.

The yard built ships, but for most of its history its major role was to supply, overhaul, and repair them. For years its ropewalk provided all the Navy's line, while its chain forge turned out all its die-lock chain.

The navy yard's most famous resident is the Constitution, moored here since 1897. Each year more than 500,000 people visit to tour her decks and learn about her past. In her heyday the Constitution shipped a crew of about 450 men; today her complement numbers around 50, both men and women, who have one foot in the Navy's high-tech present and another in the era before the reincarnated Merrimack closed the door on the days of wooden ships and iron men.

Old Ironsides' MuseumBy Tom HuntingtonBefore or after touring the Constitution, visitors to the Charlestown Navy Yard can get a good overview of the frigate and her history at the USS Constitution Museum. Located in the navy yard's Building No. 22, a sturdy granite structure that once housed the pumps for Dry Dock No. 1, the museum is a private, non-profit institution that works closely with the Navy and the National Park Service. Admission is free. Visitors can walk a recreated portion of the Constitution's gun deck and learn about the maneuvers that brought her victory over the Guerrière, Java, Cyane, and Levant. Kids will enjoy trying out a hammock and seeing how the frigate's cannon were fired. The museum's collection includes relics-such as walking sticks, a cannon, and an eagle that adorns the front of a desk-carved from wood taken from the Constitution during her various restorations, and two very large, detailed models of the frigate. One of the museum's smaller models shows how the Navy used the Constitution as a guinea pig in 1821 to test a "propello marino," an experimental man-powered paddle wheel. Another depicts the Constitution at her lowest point, when she served as a receiving ship (1882-97), complete with a barracks-like structure erected over her decks. The museum also features portraits of the Constitution's best-known commanders, Isaac Hull and William Bainbridge. In Gilbert Stuart's 1807 portrait, Hull has delicate curly hair and appears a bit plump. An exhibit next to the portrait contains items testifying to the nation's joy at his 1812 victory over the British frigate Guerrière and contains presentation pistols, a sword, and a silver urn that bears his portrait. Bainbridge's portrait, painted in 1822 by Sarah M. Peale, shows a sterner man who has long sideburns and appears somewhat jowly. In 1804, Bainbridge was in command of the Philadelphia when the frigate ran aground and was captured off Tripoli during the U.S. campaign against the Barbary pirates. He spent 19 months in a Tripoli prison. According to a museum exhibit about the Barbary Wars, Bainbridge smuggled confidential information to U.S. authorities by way of the Danish consul, writing letters containing secret messages in an invisible ink that became legible when held over a candle flame. Bainbridge was "a man who held grudges for decades," according to Commander Tyrone G. Martin, U.S. Navy (Retired), in A Most Fortunate Ship, his definitive history of the Constitution. One of his grudges was with Hull, with whom he began feuding when Bainbridge returned from command of Old Ironsides and tried to supplant Hull as commandant of the navy yard. In 2000, the museum opened the Samuel Eliot Morison Memorial Library, which is available to the public by appointment only Monday through Friday 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. To make an appointment, call (617) 426-1812, ext. 118. Also important for visitors-especially families with kids in tow-the USS Constitution Museum has a fine gift shop. You can find more information about the museum on the Web at www.ussconstitutionmuseum.org. |

On this bright October morning, the Constitution appears a little spare and truncated, with most of her spars removed and topmasts lowered in preparation for the harsh New England winter. On deck, crew and guests have assembled to celebrate her birthday. A table on the main hatch holds a cake, frosted in yellow and blue. The crew lines up in orderly rows on the port side, and the officer of the deck rings the ship's bell to announce the arrival of Commander Tom Graves, the Constitution's 69th captain. After Graves awards plaques and citations to various crew members, the oldest and youngest members of the crew together grasp a cutlass and slice the cake. Other crew members hand out metal cups of steaming grog to sailors, civilian workers who help keep the vessel shipshape, and staff members from the USS Constitution Museum. Graves lifts his mug. "To the ship," he toasts. "Happy birthday."

Party over, the officer of the deck rings the bell as Graves strides down the gangplank. "Constitution departing," she announces. The rest of the crew remain on board and receive their assignments for the day. It's now business as usual at the start of the Constitution's 209th year.

If all had gone according to plan, this birthday would have been celebrated on 20 September, the day the Constitution was supposed to have been launched. On the first attempt, however, the frigate moved only 27 feet before she became stuck. Two days later, she gained another 31 feet. Finally, on 21 October 1797, the Constitution slipped into the water "with such steadiness, majesty, and exactness, as to fill almost every breast with sensations of joy and delight, superior by far to the mortification they had before experienced," wrote the Columbian Centinel.

It was an inauspicious start to a storied career. During the War of 1812, the frigate became a point of pride for a young nation contending with the naval colossus of Britain. The United States had 18 naval vessels; Britain had more than a thousand. She may seem large today, and in her day she was the most powerful frigate in the world, rated at 44 guns and carrying up to 60. But the Constitution was not particularly imposing when compared with a British first-rate ship of the line mounting up to 120 cannon. Nevertheless, aided by her speed, stout live-oak construction, and relative strength, the Constitution won victories over British vessels of similar size. During a short slugfest on 19 August 1812 off Nova Scotia, the ship, under the command of Captain Isaac Hull, defeated the British frigate Guerrière. It was during this battle that the Constitution earned the nickname by which she is still remembered. Seeing enemy cannonballs glancing off her sides, a crew member-his name long forgotten, his words now immortal-exclaimed: "Huzzah! Her sides are made of iron!"

On 29 December 1812, "Old Ironsides," then under the command of Captain William Bainbridge, dealt out similar treatment to the frigate HMS Java off the Brazilian coast. On 20 April 1815, Captain Charles Stewart demonstrated superior seamanship when he commanded the Constitution to victory over the British frigate Cyane and corvette Levant.

Although she was not launched here, the Constitution has strong links to the navy yard. It was her designer, Josiah Humphreys, who suggested the government consider Charlestown if it wanted a navy yard in the Boston area. The frigate's first commander, Samuel Nicholson, served as the yard's first commandant. And in 1833 the Constitution became the first vessel to use the facility's John Quincy Adams Dry Dock, also known as Dry Dock No. 1. The frigate was then 37 years old, and rumors flew that the Navy planned to scrap her. Oliver Wendell Holmes aroused public opinion in her favor when he wrote the poem "Old Ironsides," and Hull himself took temporary command to bring her into the dock for a lengthy restoration.

At the time, the dry dock was brand new, an impressive granite tub 305 feet long, 30 feet deep, and 60 feet wide with a complex of pumps, tunnels, valves, and other assorted systems to fill and drain it. Loammi Baldwin designed the dock, and Alexander Parris, Boston's leading architect-Quincy Market is also his work-oversaw its construction. (During his 20-year stint at the yard, Parris designed many of its buildings, including the ropewalk.) Once the dry dock was completed, the yard could service any ship in the Navy without the need for "careening," literally beaching a vessel and tipping her on her side so workers could work below her waterline.

The yard commandant at the time was controversial Commodore Jesse D. Elliott. An ardent supporter of President Andrew Jackson's, Elliot defied Navy regulations and commissioned a figurehead of the president to adorn the Constitution's bow. The choice did not sit well in Boston. Elliot was aware of the angry reaction, and once the Constitution was refloated and anchored off the navy yard, he posted a careful watch to make sure nothing happened to the figurehead. Nonetheless, on 2 July 1834, Bostonian Sam Dewey used the cover of an intense thunderstorm to row across the Charles River, climb onto the Constitution, and saw off Jackson's head. In an equally brazen move, Dewey took the head to Washington and delivered it personally to Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson. The Constitution's figurehead, meanwhile, was repaired, and "Old Hickory" graced Old Ironsides' bow until the 1870s.

When the Constitution had first entered Dry Dock No. 1, the structure was an engineering wonder, but by the 1850s the dock was too small to accommodate the Navy's biggest ships, so it was lengthened to 370 feet. It was extended yet again in 1947-48 to its current length of 398 feet.

Today the dry dock has a somewhat derelict appearance, an impression not helped by its current occupant, the rusting hulk of the coastal steamship Nobska, which began plying the waters off Massachusetts in 1925. She arrived here for restoration in 1996 and was supposed to be out within four years, but the foundation fixing her went bankrupt. The Cassin Young was scheduled to move here in 2003 for a two-year refit, to be followed by the Constitution. Those plans have been foiled by the Nobska, which will probably soon rendezvous with the scrappers.

From inside, the oldest extant dry dock in the country appears to need some work itself. Its granite blocks remain solid, but weeds grow in the cracks between them. Once the steamship has been removed, it will take a year or so to spruce up the facility. Then it will be pumped full of water. The hollow caisson door will be emptied, unhinged, and floated away, and the dock will be ready for the Cassin Young.

On one side of the dry dock is a space that's cluttered with old hardware and large, weathered chunks of trees. This is the laydown area, a storage space for materials for ship repair. Some of the hardware was intended for the unfortunate Nobska. The tree pieces are sections of live oak for the Constitution. Contractors working for the Navy locate pieces, especially after hurricanes, and ship them here for use later. "Live oak doesn't mind getting wet so they might leave it out here for years," says Vince Kordack, a park ranger who has been at the navy yard since 1986. "They put a number on it and some coating, and if they need a piece [they] take it over to the M&R shop, cut it out, and put it on the ship."

M&R (maintenance and repair) is the last bastion of the yard's main activity. The long granite building, on the other side of the dock past a working 600-ton portal crane, dates from 1847. "This building is still used by the . . . repair section of the Navy detachment for Boston," Kordack says. "So in here you have what might be described as the best crew of wooden-ship maintenance people in the world. The only sailmaker in the Navy is employed here. Two of the handful of riggers are here." These civilian employees are responsible for much of the maintenance of the 208-year-old frigate just across the yard. "They do a magnificent job on her," Kordack asserts.

Overlooking it all from a slight rise on the yard's edge is the oldest and certainly the most elegant building here, the Commandant's House. This large brick structure was built in 1805 to serve as quarters for the officer in charge of the yard. Two of its occupants were Captains Hull and Bainbridge. When Bainbridge, an irascible man, first moved into the house in 1812, he complained that the Greek Revival structure was "built on too expensive a scale, very inconvenient as to its construction, and very slight and meanly built." Some changes have been made since Bainbridge made his caustic assessment. The main entrance, on the side facing away from the yard, now stands eyeball-to-eyeball with a large, vine-covered wall built in the 1970s to separate the yard from busy Chelsea Street. On the side facing the yard is a large wrap-around porch, the center section enclosed and with arched windows, added as a Works Progress Administration project in the 1930s.

Plan Your VisitBy Tom Huntington The Charlestown Navy Yard is part of Boston National Historical Park, (617) 242-5601, www.nps.gov/bost. The navy yard is open daily 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Free 90-minute guided tours are given during the summer months. The visitor center, which has exhibits about the nearby Battle of Bunker Hill and shows the movie "The Whites of Their Eyes," is open daily 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. There is a fee for the movie. The destroyer USS Cassin Young is open from January through March for guided tours only. From April through November she's open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. for guided and self-guided tours. The USS Constitution is a commissioned warship, but she is open to the public. From 1 April to 31 October her hours are Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5:50 p.m. The rest of the year she's open Thursday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 3:50 p.m. Tours depart every half-hour, starting at 10:30 and ending at 3:30. Visitors should arrive a half-hour early to get through the security screening. The ship's official site, www.ussconstitution.navy.mil, provides information about special events, such as the regular turnaround cruises the ship makes each year so that she will weather evenly. The USS Constitution Museum is next to Dry Dock No. 1 and open daily 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. 1 May through 15 October, and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., 16 October through 30 April. Admission is free. Once considered a somewhat downtrodden part of Boston, Charlestown is now in the midst of a revival. The changes have extended to portions of the navy yard, which has become valuable waterfront property. Accommodations in Charlestown include the Constitution Inn, 150 Second Avenue. It's just a stone's throw from the yard. The 147-room inn offers reasonably priced (for Boston) accommodations in rooms that come equipped with kitchens. It also has a swimming pool and fitness center. Military personnel can stay for half price. (617) 241-8400 or (800) 495-9622; fax (617) 241-2856; www.constitutioninn.org. Also nearby is the Residence Inn Boston Harbor on Tudor Wharf, 34-44 Charles River Avenue. (617) 242-9000 or toll free (866) 296-2297; fax (617) 242-5554; http://marriott.com/property/propertypage/BOSTW. The nearest stop on Boston's subway system, the T, is Community College, a fair hike away from the yard. However, a free shuttle service links the navy yard with North Station and Massachusetts General Hospital, two stops on the T's red line. For those who prefer to feel a salt breeze in their faces, for $1.50 a water shuttle takes passengers from Pier 4 at the foot of Dry Dock No. 2 into downtown Boston near the Aquarium T stop. |

The house is being refurbished for functions, and people attending events here will be following in distinguished footsteps. Presidents James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Johnson, and both Roosevelts were entertained here. So was President John F. Kennedy, whose congressional district included the navy yard. The Marquis de Lafayette stopped by during his triumphal return to America in 1824.

Sometime between 1919 and 1921 a young Japanese naval officer who was taking courses at nearby Harvard College visited the Commandant's House for social visits to play cards. His name was Isoroku Yamamoto, and years later he planned the attack on Pearl Harbor. "He played poker here on four or five occasions," Kordack points out. "It would be nice to see who the players were and see if they ever faced each other during the war, whether they learned any insights when they were playing."

When Yamamoto visited here, the navy yard had begun settling into a decline that lasted into the Great Depression. Throughout its history, its condition mirrored the ebbs and flows of military funding. In the 1850s, when the yard built the brick octagon called the Muster House to keep track of the workforce, only about 1,200 men worked here. Once the Civil War broke out in April 1861, the force grew to around 10,000.

In the years before the Spanish-American War, the yard's continued existence hung by a thread, almost literally, since its ropewalk was almost the only thing keeping it open. A low and exceptionally long granite structure, the ropewalk was built on the yard's edge because its hemp and tar were so flammable. Today the building, a quarter-mile long, has been shut down, its future uncertain. Ironically, fire helped do it in, but the blazes were deliberately set as acts of vandalism in recent years, long after the building stopped making rope in 1971.

By the late 1890s the ropewalk was one of the yard's few bright spots. The work force fell to only several hundred, "so few men that they were lost to sight in the big buildings," reported the Boston Sunday Herald in 1897. Then the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, and the resulting Spanish-American War boosted employment levels to more than 1,500.

It also spurred authorization of a new dry dock. Today Dry Dock No. 2 is filled with water, turning it into a long artificial pond opposite Shipyard Park and its Korean War memorial. Construction began in 1898. One hundred thousand barrels of cement and 21,500 cubic yards of granite from New Hampshire's White Mountains were used to build the 750-foot-long dock, which was finally completed in 1906. That year, however, the Royal Navy launched the 527-foot HMS Dreadnought, which ushered in an era of even larger battleships that the dock could not accommodate.

The yard remained busy after the Spanish-American War and became even more so when the United States entered World War I. In 1914, the yard repaired 42 vessels. Four years later the total was 215. The workforce ballooned as well, climbing to almost 13,000 by April 1919.

Work slowed in the 1920s, but some workers kept busy on another restoration of the Constitution. Once again the venerable warship settled into Dry Dock No. 1, entering on 16 June 1927 and remaining for almost three years.

Things began looking up in 1932, and the yard's savior turned out to be the destroyer. President Franklin D. Roosevelt took steps to increase the fleet, and the Charlestown yard began reaping the benefits. In May 1933 yard workers laid the keel of the Farragut (DD-348) -class MacDonough (DD-351) in Dry Dock No. 1. Over the next 11 years, the yard built a total of 36 destroyers of various classes, usually constructing two of them simultaneously in the same dry dock. On 20 October 1939, four destroyers emerged from Dry Dock No. 2.

After Yamamoto's attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the nation into war, the navy yard entered its busiest period ever. During World War II it constructed 174 vessels, including destroyers; submarines; destroyer escorts; landing ships, tank (LSTs); and landing ships, dock (LSDs). Many of the destroyer escorts were constructed in a new, 518-foot dry dock, completed in 1942 and called Dry Dock No. 5.

The Cassin Young was built in San Pedro, California, but she serves as an example of the 14 Fletcher-class destroyers constructed here. Launched in 1943, Cassin Young was named after a Navy commander who earned the Medal of Honor at Pearl Harbor and died in command of the heavy cruiser San Francisco (CA-38) during the Battle of Guadalcanal. His namesake also felt the sting of battle. On 30 July 1945, a Japanese kamikaze struck the ship near her forward stack and exploded. Twenty-two men on board Cassin Young were killed and another 45 wounded. After being refurbished here for service in the Korean War, the destroyer was decommissioned for good in 1960 and opened to the public at the navy yard in 1981. Her home now is Pier 1, where her sharp prow points at Dry Dock No. 1 like an accusing finger directed at the tardy Nobska.

Except for a slight spike during the Korean conflict, the Boston Naval Shipyard experienced a steady decline in its workforce after World War II. The yard launched its last ship, the Suffolk County (LST-1173), in 1956, but it continued repair and overhaul work at ever decreasing levels of activity. In 1973, the yard worked on only 14 ships. By then its cramped facilities were old and outmoded. When the ropewalk closed in 1971, only 19 people worked there. The yard itself finally shut down in 1974.

It was the beginning of some tough times for Charlestown, but in recent years the area has rebounded. The massive, controversial, and very expensive highway and tunnel project known here as the "Big Dig," passed through this end of Charlestown. In the project's wake the area has witnessed a burst of new development, bringing with it upscale shops and restaurants. Luxury condominiums and residences now stand on real estate once occupied by shipways.

One thing remains constant, and that's the Constitution. Motorists passing by on the nearby bridges and overpasses still spot the old frigate's masts and spars rising from the waterfront, like some kind of anachronistic mirage.

On Old Ironsides' birthday, Petty Officer First Class Dave White guided visitors around the frigate's decks. White, from Beaumont, Texas, has been in the Navy for 6½ years. Before being assigned to the Constitution he was a fire controlman on the USS The Sullivans (DDG-68) targeting cruise missiles. He told his audience that it is an "honor and a privilege" to serve in the Constitution and reminded them that the vessel is still a commissioned warship, with a Navy crew. "We're not actors dressed up like sailors," he says. "We're sailors acting like tour guides."

And the Constitution is not merely a museum piece. She's a commissioned warship, a part of today's Navy, even at the ripe old age of 208.