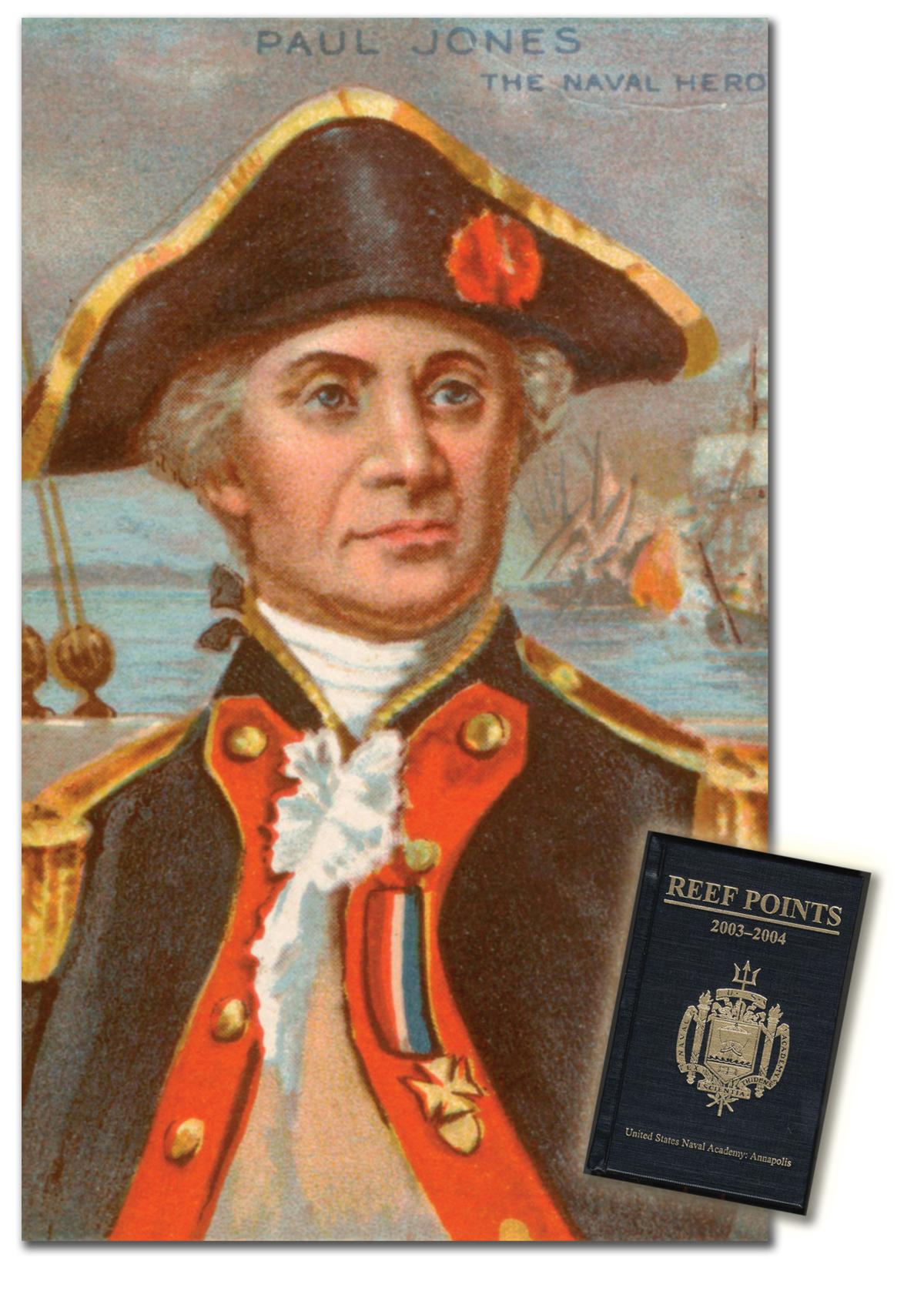

The "Qualifications of a Naval Officer" quotation variously attributed to John Paul Jones and force-fed to U.S. Naval Academy midshipmen in the publication Reef Points presents a clear sign of naval transformation at the turn of the 20th century. The action of a recent Commandant of Midshipmen, however, officially acknowledges that Jones had nothing to do with this 100-year-old mantra.

In 1986 naval historian James C. Bradford carefully constructed a case proving that Augustus C. Buell (1847-1904) was a fabricator. "Qualifications of a Naval Officer," long memorized by all midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy, was not written by John Paul Jones, as first cited by Buell in his 1900 two-volume Paul Jones: Founder of the American Navy.1 Rather, Bradford convincingly argued in a 33-page pamphlet published by the Naval Historical Foundation that the popular biographer had rewritten some of Jones's letters and created other documents to offer turn-of-the-century naval officers a model of modern professionalism.2

The Academy's Nimitz Library cataloged numerous copies of Bradford's pamphlet, "The Reincarnation of John Paul Jones," and subsequent scholarly treatments of the naval hero lamented that Buell's fabrication continued to be taught to plebes every summer through the student handbook, Reef Points. But the Academy did not accurately attribute the quotation until 2003.

After a memo brought the issue to his attention, then-Commandant of Midshipmen Marine Corps Colonel John Allen considered the need for historical accuracy while also recognizing the positive impact the forged texts traditionally had played in the education of naval officers.3 The colonel's prudent solution was to retain the quote in the 98th edition of Reef Points while changing its attribution to read as follows: "Written by Augustus C. Buell in 1900 to reflect his views of John Paul Jones." Directly following this ascription are four authentic quotations by the Revolutionary War hero that now-Brigadier General Allen hopes will in time replace the forgery.4

Whether this will end the controversy is debatable. Corporate memory is notoriously short, and heritage (or "collective memory" as the shared memories of a group or institution are known to scholars), once incorporated, is very difficult if not impossible to alter. Unless serious discussion accompanies the recent changes in Reef Points, Buell's fabrication likely will be reinstated at some later date. Past attempts by Academy officials to remove "Qualifications" from the curriculum failed when subsequent administrations, enamored by its effectiveness in building group cohesion, re-instituted the much beloved prose.

Except for the original fabricator, Augustus C. Buell, this story has no villains. Naval Academy officials who maintained the fabrication over the years as well as critics who periodically called attention to its fictitious nature all did so in the best interest of the Navy and its midshipmen.

Dr. Bradford was not the first historian to question the reliability of Buell’s scholarship. Because few in the United States had placed much importance on John Paul Jones prior to the turn of the 20th century, Buell’s declaration that the naval hero had actually founded the Navy caused some immediate debate. Certainly Jones had been admired greatly during and after the American Revolution for his glorious, even audacious, victory over HMS Serapis. And a flurry of biographies during the 19th century celebrated Jones as a brave, self-made man of action.’ The Navy itself, however, had not held him in very high esteem; his exaggerated sense of personal honor, poor leadership skills, violent temper, sexual excesses, and questionable national loyalty while serving abroad prevented him from being considered a model professional officer.6

Therefore, when Buell’s biography of Jones cited newly discovered evidence proving that the naval hero deserved the coveted title, “Father of the Navy,” critics asked to see his documentation and questioned the myth- maker’s contention that Jones held progressive-era views on patriotism and professionalism.7 Buell, a journalist, civil engineer, and shipbuilder, responded defensively. He had failed to keep his research notes, he explained to reviewers, because he had assumed his study would be accepted as authoritative.8 He died in 1904 under a cloud of suspicion but before the public became aware of his wholesale distortions.

A year following Buell’s death, the John Paul Jones myth became firmly, almost inextricably, planted in the nation’s collective memory when President Theodore Roosevelt designated Jones as the Navy’s new patron saint. Roosevelt, who years earlier had dismissed the naval hero as merely a “daring corsair,” publicly embraced Buell’s interpretation after learning that Ambassador Horace Porter had discovered the Revolutionary War hero’s coffin in an abandoned Parisian cemetery. Roosevelt did so as part of his publicity for plans to build a large, offensive fleet of capital warships staffed by a modern, professional officer corps. Well versed in modern public relations techniques and supported by historical and sociological principles, Roosevelt translated his proposed policy measures for the Navy into an epic heroic struggle to achieve the nation’s destiny.

Progressive-era historians, like Roosevelt, often celebrated heroes so citizens would be inspired to a national character worthy of democratic participation. Roosevelt established his own credentials as “heroic leader” in a public relations campaign that incorporated the grand showmanship techniques of none other than P. T. Barnum (1810-1891) and William “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846-1917). The pitch included daily press releases, a close personal relationship with newspaper reporters, and participation in ceremonial events designed to impress the public and identify his policies with traditional American values.

In The Rough Riders: Men of Action (serialized beginning in 1899) Roosevelt, then running for Governor of New York, lost all objectivity as he reshaped events of the Spanish-American War to present himself and his volunteer militia in the most flattering light. According to political scientist Bruce Mirhoff, Roosevelt’s self-depiction as “[t]he cowboy of the Dakotas, the police commissioner patrolling New York’s mean streets, the Rough Rider charging up San Juan Hill, the progressive president scourging predatory capitalists, the African big game hunter, and more” were concerted efforts to make him a worthy leader and “the first great American hero of a new age of mass media.”9

Ambassador Porter’s discovery of Jones’s grave effectively served the president’s purposes; the venerated image garnered considerable publicity for battleship construction and promoted a collective memory of a naval past that embraced the country’s new, expanded international maritime role.10 At the direction of the President, the Navy sent Rear Admiral Charles D. Sigsbee and a squadron of four cruisers to Cherbourg, France, to retrieve the body and began planning a year of elaborate celebration.

“Every officer in our Navy should know by heart the deeds of John Paul Jones,” Roosevelt charged the following spring during an international commemoration ceremony at the Naval Academy armory building (now Dahlgren Hall), “and should feel in each fiber of his being an eager desire to emulate the energy, the professional capacity, the indomitable determination and dauntless scorn of death which marked John Paul Jones above all his fellows.”11 Porter’s discovery of Jones’s body and the pomp and circumstance of the year-long commemoration only increased interest in and acceptance of Buell’s biography, which had been reprinted with an appendix on Porter’s 1905 exhumation.12

Shortly after the ceremony, Anna De Koven, the leading Jones historian of the era, publicly exposed the Buell forgery on the front page of the magazine section of The New York Times. De Koven, who had examined Jones’s handwritten letters held by the Library of Congress and other repositories, identified the most glaring of Buell’s lies and revealed the depth of his academic dishonesty. “The most daring forgery of all,” she concluded, “was a September 14, 1775 letter Buell claimed Jones wrote to Joseph Hewes of the Marine Committee of Congress regarding the founding of the Navy.”

De Koven noted that this communication, from which an excerpt later became known as “Qualifications of a Naval Officer,” would have been impossible. Not only was Jones in hiding in September 1775 after killing a mutineer, but the Marine Committee also did not even exist until a full month after the letter’s date. The fabricated document had become the basis of Jones’s new lofty status, De Koven charged, because “admiring readers and reviewers [had] . . . pronounced it truly prophetic in its far-seeing wisdom. Having been composed more than 100 years after those first stumbling days of our navy, it is not surprising that its theories and its advice should seem to be prophetic.” Studying this letter and other spurious materials, De Koven concluded that Buell’s Paul Jones, “although vastly entertaining as a romance, [was] . . . utterly valueless as history.” As a result, Buell’s publisher, Charles Scribner and Sons, withdrew the discredited work from circulation and replaced it in 1913 with De Koven’s more reliable work, The Life and Letters of John Paul Jones.”14

Despite the fact that journalists and academics immediately embraced De Koven's charges, the John Paul Jones title as Father of the Navy persisted in the popular imagination. The New York Times had congratulated De Koven for her dispassionate research, which had "completely disposed of the pretensions of the late Augustus C. Buell as a serious historian."15 Albert Bushnell Hart, president of the American Historical Association, declared in 1909 that no other "bold and creative act of imagination . . . in American history surpasses Buell's recent John Paul Jones."16

In the following years, respected scholars such as Lincoln Lorenz and Samuel Eliot Morison also warned readers of Buell's unreliability.17 Less careful biographers, however, such as Mary Mac Dermot Crawford, Valentine Thomson, and Phillips Russell, promulgated the myth by citing the fraudulent historian in support of their own glorifications of the nation's naval past.18

In 1956, hoping to bury Buell forever, Milton W. Hamilton, a member of the Division of Archives and History in Albany, New York, systematically reviewed all of Buell's scholarship—biographies of Andrew Jackson, Sir William Johnson, William Penn, and even his much-cited Civil War memoirs—and concluded that the bulk of the materials were "'pure Buell'—legendary, garbled, or fiction." According to Hamilton, the books' "outline[s were] factually correct, but the detail was fabricated to meet the romantic ideas and heroic concepts of the author." Unfortunately, noted Hamilton, Buell had "perpetuated myths and inventions to the point where it often require[d] considerable research to disprove oft-cited episodes."19

The Navy became aware of the problems with Buell's scholarship at about the same time as the Jones commemoration ceremony and De Koven's subsequent exposé. But the service, despite efforts of a number of individuals to correct the historical record, had difficulty distancing itself from the mythmaker's well-crafted prose. Both former Secretary of the Navy John D. Long and Admiral George Dewey applauded Buell's new romantic interpretation of John Paul Jones.

In 1901, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Frank Warren Hackett praised Buell in a speech delivered at the Naval War College for bringing to light "the grand proportions" of the naval hero. "Hitherto the world has only known Paul Jones simply and exclusively as a sea fighter, the foremost of any age," Hackett charged. And he went on:

We now, and most of us for the first time, see in him a statesman, a diplomat of rare ability, and an accomplished man of the world. At last an adequate conception of our hero being thus presented to his countrymen, it would be an act of tardy justice to set up at Washington a memorial to John Paul Jones, where as yet none exists.20

But by 1909, Hackett responded to the De Koven exposé by amending his published speeches with an appendix that included a letter from the Librarian of the Navy Department completely discrediting "Qualifications of a Naval Officer."21 The following year in the U.S. Naval Institute's Proceedings, naval historian Charles Oscar Paullin dismantled Buell's argument that Jones had founded the Navy. "No one man founded our navy," Paullin wrote in the March issue. "Its establishment was a composite work in which John Adams, Stephen Hopkins, Robert Morris, Joseph Hewes, John Hancock, John Paul Jones, Esek Hopkins and many others participated."22

On 2 July 1920 Rear Admiral William S. Sims wrote a memo to the Bureau of Navigation, informing the agency of the true source of the bogus quotation.23 The next year the Department of State also alerted the Secretary of the Navy of its spurious origins.24 But as Sims reported in an article for World's Work six years later, the Navy was still using "Qualifications" on fitness reports.25

Secretary of Navy Curtis D. Wilbur responded to Sims's highly critical article by requesting that Assistant Librarian Louis H. Bolander investigate the various Jones quotes then in use by the Navy.26 Bolander's somewhat defensive report in the July 1928 issue of Proceedings explained that the Naval Academy English department had used an authentic Jones letter containing similar phrases as a midshipman motto perhaps as early as 1876. The librarian shrewdly sidestepped the question of whether or not the Buell fabrication was also in use in the school at that time. But he did agree with De Koven's earlier finding that it came from an invented source.27

A further modification occurred in 1987, undoubtedly in response to Bradford's excellent study a year earlier, enlarging the attribution to read "from a composite letter of John Paul Jones' phrases and clauses as compiled by Augustus C. Buell."38 Although less objectionable, it should be noted that while Jones did write things at various times similar to portions of "Qualifications," not everything in the forged texts can be found in his authentic letters and journals. In addition, Buell clearly had modernized the naval hero's views to suit his own Progressive-era conception of a professional naval officer. The Academy made no further revisions to the attribution until 2003, when Colonel Allen made the modification that credited the quote directly to Buell.

Naval Academy midshipmen reactions to a suggestion that the Buell quote be replaced in Reef Points with excerpts from authentic letters from John Paul Jones has met with mixed reactions and, at times, heated exchanges. Student comments in discussions held by one Naval Academy professor suggest that over time "Qualifications" does play a positive role in building group cohesion. Prospective students attending a summer seminar session titled "In Search of John Paul Jones" generally were unfamiliar with the quotation and were surprised, when informed of its true source, that there was even a debate over its preservation.

Plebe students enrolled in American Naval History demonstrated considerably more allegiance to the words they had recently memorized during Plebe Summer. When told that the quote was fraudulent, however, a number cited the school's honor concept as justification for its elimination. In addition, few believed the quote would hold much value with midshipmen if not attributed directly to Jones.

The upper classes’ response, however, has been dramatically different, with few supporting any change. Some second- and first-class midshipmen expressed annoyance and anger, perhaps a natural response to a perceived outsider’s debunking of cherished traditions. Comments such as, “but it works,” and, “the words are so good it doesn’t matter who said them,” frequently have been made during class discussions. Considerably less often, bewilderment has been directed toward the Academy’s administration for employing, in these individual students’ evaluation, a fabrication to reshape their character.39 As historian Glenn May has aptly remarked, “[t]he exposure of hero myths invariably causes pain, since all of us . . . have a deeply felt need for heroes.”40

The upper classes’ devotion to preserving “Qualifications,” no matter its author, demonstrates how collective memory increases in strength over time. Such a connection creates the sense of corporateness or collective self- consciousness deemed so important by Samuel Hunting- ton in the education of a professional military officer.41

"Qualifications of a Naval Officer," once called "the moral and intellectual charter of Annapolis, and the sure and everlasting warrant of Jones's title to be called the Father of the Navy," has become one of the sacred canons of naval heritage. 42The question remains, however, whether or not Naval Academy midshipmen, taught to be critical thinkers as well as dutiful officers, are up to the challenge of separating fact from fiction in the historical record without sacrificing the inspiration traditionally found in collective memory.