Read a preview of From Frigate to Sloop of War.

Read author Geoffrey Footner's response to this article.

Is the ex-USS Constellation displayed in Baltimore today a frigate, much modified but built in Baltimore in 1797, or is it a sloop-of-war, bearing the same name and built in Norfolk in 1853? The question had long vexed naval historians, and proponents of both theses waged a sometimes-bitter battle in print from 1948 until 1995.

In 1991 a small interdisciplinary team of historical investigators from the U.S. Navy's David Taylor Model Basin discovered new, clear, and simple evidence that resolved, we believed, the notorious "Constellation Question." That evidence indicates today's Constellation is an 1853 sloop-of-war built ("rebuilt") near Norfolk to an entirely new design, containing a small amount of hull material from the old frigate. Current interpreters of the ship properly display and outfit her as a sloop-of-war.

Since the 1991 publication of our official 200-page technical report, Fouled Anchors: The Constellation Question Answered, we have contributed several journal articles and have continued collecting information regarding the two Constellations. In late 2002 the Naval Institute Press published Geoffrey Footner's USS Constellation: From Frigate to Sloop of War, which exhumes the old question and challenges our findings.1

Same Old, Same Old

Placed in the historical context of the controversy, Frigate to Sloop merely repackages the same basic idea the 1797 proponents of the ship have resorted to since before 1961. That is, the old frigate was modified extensively before she was brought into the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard in 1853, and that a substantial portion of the old frigate was converted into the rebuilt sloop that emerged from the yard in 1855. Therefore, those proponents have said, the Constellation in Baltimore today has had continuous physical existence since 1797.2

Occam's Razor

Our 1991 findings were relatively simple. In 1989 we discovered in the U.S. Naval Academy Museum the designer's half hull model used by Naval Constructor John Lenthall in 1853 to prepare the new design for the sloop-of-war Constellation. The model matches the ship today and contemporaneous plans of the 1855 sloop, and it is prime evidence supporting our contention.3

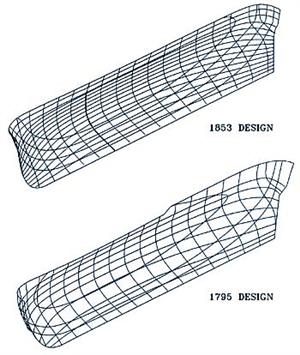

In January and February 1853, just before the old frigate was hauled from the water and eventually broken up, Gosport Navy Yard workers made a set of drawings recording the twisted hull shape and hogged keel of the 56-year-old frigate. These survey drawings show that the old frigate had not been modified significantly below the waterline between 1797 and 1853. Computer-aided naval architectural studies confirmed that no part of the sloop design reasonably matched the shape of the old frigate's hull.4

Claims that the hull form of the sloop Constellation bears a deliberate relationship to the frigate must account for the 1853 designer's half model. Assertions that the underwater lines of the frigate were altered significantly before 1853 must account for the 1853 survey drawings of the old frigate's hull and keel.5

Credit: THE KEDGE-ANCHOR, OR YOUNG SAILORS' ASSISTANT, 1854

In preparing the 1991 report, we discovered that most of the historical documentation used to defend the 1797 origin of the ship had been forged. We discovered dozens of widespread forgeries and determined that in all likelihood the forger was a now-deceased long-standing employee of the ship in Baltimore, and that he created most of the forgeries between 1956 and 1965. His attempts to defend the 1797 origin of the ship were aimed to bolster efforts to change the sloop into a frigate. He was not motivated by money, and creating dozens of spurious documents was not in itself illegal. But the forger probably crossed the legal line when he amended original ship's drawings and planted copies of his work in the collections of Federal and institutional archives. His trademarks now are relatively easy to spot.6

Nevertheless, until 1991 the forgeries had fooled or perplexed experts for decades. Judging by Frigate to Sloop, they continue to hoodwink the unwary or desperate. Our report ended with the motto, caveat historicus ("historian beware"), and it is disappointing that the warning already has fallen on deaf ears. To read more about the forger and his work, our report can be found free on the Internet at http://www.dt.navy.mil/cnsm/faq_13.html.

The Dog Ate My Documents

The central contention of Frigate to Sloop is that the frigate Constellation was "rebuilt" four times—in 1812, 1829, 1839, and 1853-55. Covering all the bases, the book defines "rebuilt" as a repair event so extensive that the underwater hull lines of the ship may have been altered significantly or the hull may have been replaced. Supposedly, the underwater hull form of the ship was redesigned during each of the first three "rebuilds" and the frigate's hull incrementally became more sloop-like, emerging fully transformed in 1855. We have held consistently that the Constellation was repaired many times, but was rebuilt (built anew to a new hull design) only once, that is, at Gosport between 1853 and 1855.7

Frigate to Sloop's "four-rebuild" thesis is hammered home repeatedly, regardless of the belated revelation halfway through the book that the author was unable to find any authentic direct evidence that the frigate's underwater lines were changed before 1853. Supposedly, dozens of letters, reports, drawings, calculations, work orders and logs, labor reports, supply requisitions, and offset tables are "missing" from various archives and from time periods spanning a half-century. Since "the dog ate my documentation," what remains? Frigate to Sloop presents a multilayered hodgepodge of second-quality, inferential evidence concocted from subjective sailing records, unreliable and vacillating ship dimensions, financial records, guesstimation, creative arithmetic, one nonexistent document, six documents allegedly bearing wrong dates, and a few forgeries unwittingly used at important junctures—all stuck together with lots of conjecture posing as fact.8

The 1812 "Rebuild"

Because the records at the Washington Navy Yard reportedly were burned in 1814, apparently only a three-sentence contemporaneous narrative exists to describe work done there to the frigate. No correspondence, measurements taken from work, drawings, or design models are to be found, but Frigate to Sloop confidently declares that she was rebuilt entirely from her floors upward, 14 more inches were added to her molded beam, and her underwater hull was redesigned and "refaired from stem to stern." Did this happen? The first drydock in the United States was commissioned in 1833. Prior to that time U.S. naval vessels were repaired in one of three ways: afloat, on building ways, or by careening ("heaving down") at a wharf. Underwater hull structural repairs afloat were limited to piecemeal replacement of timbers worked from inside the ship while the hull planking remained intact and watertight. The shape of the underwater hull could be retained but not altered.9

Credit: INDEPENDENCE SEAPORT MUSEUM, PHILADLEPHIA / LEON POLLAND PAPERS

The few words describing the work done at Washington in 1812 indicate she was brought up to the wharf and remained afloat. Her hull was reconstructed above the lower futtocks, not the floors. Some of her futtocks and floors were replaced, and her beam was extended 14 inches at the main breadth. Following these interior repairs, she remained afloat and was hove down on each side, the new bolts that had been driven from inside the hull were ring-riveted, and she was fitted with a new rudder and hardware and recoppered. The record says nothing about refairing her hull lines. Ships were hove down in the morning, and for safety they were righted ("eased-up") by nightfall. No work could be done that could not be closed-up by the time the ship was eased-up. Owing to the dangers of collapse, flooding, and hull deformation, extensive hull structure work generally never was done to a ship hove down.10

In 1992, we noted that the Constellation never fully left the water during her 1812 repairs. Consequently, her underwater hull lines could not have been altered. That the ship had never been removed from the water between her launching in 1797 and 1835 is casually, and again belatedly, mentioned in Frigate to Sloop about midway through the volume. The impossibility of changing the underwater hull lines of a ship afloat goes unrecognized.11

The 1829 "Rebuild"

Frigate to Sloop asserts that the Constellation's hull lines were modified again in 1829, her stern structure was updated, and another 17 inches was added to her beam. Once more, her hull was redesigned and "refaired from stem to stern." Like 1812, the ship was not removed completely from the water in 1829, and the book fails to consider the limitations. The book's supporting evidence of hull form changes is a table of offsets prepared during the supposed refairing of her lines in 1829 (or maybe 1828) and the direct evidence is a drawing of her stern. This looks like good proof. But is it?12

No one ever has seen the alleged 1828 offset tables. Frigate to Sloop does not use the offsets themselves as proof, it uses the supposed previous existence of them as evidence. The spectral offsets are referenced in a list of items purported to have been turned over by the Boston Naval Ship Yard to the Baltimore custodians when the Constellation was donated to them by the Navy in 1955. Frigate to Sloop supposes the offsets disappeared after the Baltimore group received them that year. The list is a typically preposterous, poorly phrased, badly typed, over-the-top forgery similar to other identified forgeries. Had it existed, this secret and illegally retained and transferred treasure trove of Federal records would have been one of the most significant collections of documents in U.S. naval history. Doubtless, the 1828 offsets, like most of the other spectacular documents on the list, are a creation of the forger's active imagination.13

Frigate to Sloop employs a well-known drawing as proof the ship's lines were altered and her stern modernized in 1829. Copies of the drawing bear two dates—1840 and, reportedly, 1829. The drawing has been suspect since it appeared several times in The Constellation Question (see footnote 4). Skilled and determined efforts dating to the 1960s have failed to locate the manuscript version. Nevertheless, Frigate to Sloop labels the original drawing as from National Archives Record Group 45, Entry 464.14

Long-standing suspicions were confirmed when, in October 2002, we discovered the manuscript drawing from which the so-called "Mizzen Mast Survey" was copied. The real drawing is a sail plan of the USS Congress, dated 1837, which the forger probably copied photographically, cropped, and then manipulated. Illustrations 3 A-C show how the forger probably created the drawing.15

1853-55 Gosport Rebuild

In 1845 the frigate Constellation was placed in ordinary (mothballs) at the Gosport Naval Ship Yard. Chief Naval Constructor John Lenthall recently had been charged with modernizing the fleet, including the Constellation. Doubtless, he planned to razee her into a sloop-of-war. Probably to help plan the shoring and blocks necessary to hold the ship upright for examination on 23 February 1853, the Constellation was measured, and a simple survey drawing of nine hull cross sections, plus a related two-part drawing of the keel, were developed in January and February 1853. These drawings combined to show the twisted hull and hogged keel of the old frigate.16

Credit: KEVIN LYNAUGH, FOULED ANCHORS

With the Constellation out of the water, Lenthall could better understand the condition of her timbers, and the recent hull shape survey confirmed her badly wracked frame. Her poor condition made the constructor decide to rebuild her as a new sloop. Intending to use part of the stockpile of pre-shaped timbers stored in the Gosport Yard, Lenthall apparently drew his preliminary draft of the new sloop in May 1853. His draft did not begin with either the Constellation's 1795 lines or, as claimed by Frigate to Sloop, with the newly acquired cross sections of the twisted old frigate. Lenthall probably began by drawing the narrowed hull lines for the 1841 frigate USS Congress, which had been the most recently designed frigate and proved a successful ship. Her length was similar to the required size of the new sloop, and much of the timber stockpile already conformed generally to her lines. Nevertheless, Lenthall abandoned the Congress's lines, and on the same sheet of drawing paper struck an entirely new set of sloop lines within the restrictions imposed by the stockpiled timber. In June he developed a more refined design. Since Congress had not appropriated money for a new ship, Lenthall resorted to building a new ship with repair money to occupy the "room" of the old ship, retaining the old name, and classifying the ship as "rebuilt."17

Designer's Half Model

Probably shortly after the June draft, the 1:36 scale, wooden, half hull model was made. Half models had been used to design every U.S. Navy ship since 1820. The model was disassembled, traced, and enlarged 36 times on the mold loft floor. The full-sized floor drawing was measured to an eighth-inch accuracy and the measurements were placed in tabular form, creating the "tables of offsets" that recorded the shape of the ship's hull. From the full-sized floor drawing, templates, or "molds," were made, indicating the shape of each of the new sloop's frames.

On 16 May 1853 yard workers began cutting up the old frigate and later started to haul out pieces of stockpiled live oak timber for the new sloop. They laid a new keel and began to erect the new vessel in a ship house about 600 yards from the old frigate. On 23 July 1853, a local newspaper correspondent touring the yard noted that both the old and new Constellation coexisted. On 12 September 1853 the commandant of the Gosport Yard asked the Secretary of the Navy for permission to auction the old timbers of the frigate.18

Recycled Timbers

Records of work and materials at Gosport do not indicate that any hull materials were transferred directly from the old ship to the new one. The local Portsmouth, Virginia, Daily Transcript's account of the sloop Constellation's launching in August 1854 specifies that four floor timbers—M, O, P, and Q, and four third futtocks, specifically 9, 10, S, and P—in the new sloop were made from some of the serviceable floor timbers of the old frigate. This would amount to about 186 cubic feet of timber in a ship composed of approximately 19,000 cubic feet of live oak, or about .01%. Transfer of a modicum of old timber from the 1797 frigate to the 1853 sloop-of-war may have been for sentimental reasons and/or to justify the Navy's classification of the sloop as the frigate rebuilt. The Navy carried her on her registers until 1908 as a sloop-of-war built or rebuilt at Norfolk in 1854.19

If any intact portion of the frigate's hull or form had been used in the new sloop, the half hull model would have been useless, because the existing ship could not have been measured, reduced to 1:36 actual size, faired, enlarged 36 times, and still retain the required accuracy relative to the existing vessel. Likewise, the model could not have been used to modify existing hull lines. The significance of the half model was published in 1991 and 1995, but Frigate to Sloop does not mention the model at all.20

1853 Hull Survey

The 1853 hull survey drawings provide direct evidence that, indeed, the frigate's underwater lines were unchanged, except for age deformation, between 1797 and 1853. Facing a monumental roadblock to the book's central contention, Frigate to Sloop attempts to re-date the drawings to an earlier period and relate them to the sloop design. Another author tried unsuccessfully in 1979 to backdate the 1853 survey. Frigate to Sloop asserts that the drawings labeled January and February 1853 actually were drawn at Boston in 1839, resurrected, and sent to Lenthall in 1853 as a reference to aid in "modifying" the frigate's hull lines into the sloop's. That the sections were drawn in 1839 is based on only one valid premise: The handwriting on one survey drawing allegedly matches the handwriting of another drawing done at Boston in 1840. Obviously, the hand does not match: One is pen-lettered and the other is cursive. Frigate to Sloop employs chiefly only six archival drawings to make its argument. Regardless of whether the drawing is real or fake, in every case but one, the date appearing on each drawing is rejected and another date must be rationalized and substituted in order to support the book's conclusion.21

The hull survey sectional drawing is penned on linen drafting cloth rather than paper. Linen drafting cloth was first patented by Charles Dowse in Britain in 1846 and was introduced to the public at Britain's Great Exhibition of 1851. The material gradually became popular in the United States in the following years. Therefore, the survey drawings could not have been made before 1851. Since the section drawings show that the lines of the frigate Constellation were basically unchanged from 1797 until her demise in 1853, the "four rebuild" theory of Frigate to Sloop is moot. By definition of the Fouled Anchors research team, she was rebuilt only once, that is, between 1853 and 1855.22

Naval architect and maritime historian Colonel Howard I. Chapelle (1901-1975) first confirmed in 1967 that one Constellation document was forged. Because of the volume of forgeries, in 1991 we did not list all the specific counterfeits in all the contaminated collections. We were concerned mainly with the 22 documents used regularly at that time to defend the 1797 origins of the ship. At several critical junctures Frigate to Sloop resorts to documentation found in poisoned sources and where no original versions can be found. Leon Polland was not the forger but doubtless he knew the identity of the culprit. Fouled Anchors, p. 77; "Query and Response," p. 262; "Apple & Orange," p. 77. For Chapelle's initial discovery and Polland's oblique acknowledgment of forgeries, see The Constellation Question, pp. 38-40, 59, 61, 63, 72, 77, 86. See also Fouled Anchors, pp. 48, 53-4, 56-9, 69-77, 85. back to article

Lacking evidence such as offsets and contemporaneous drawings, Frigate to Sloop attempts through a series of newly drawn transverse midship sections to use variations in deck measurements to show how the shape of the ship's hull changed through the alleged rebuildings of 1812, 1829, and 1839. According to the book, these drawings were created by "trial and elimination" and by applying "certain assumptions" (p. 141). This means the dimensions and drawings mutually have been adjusted to conform to the book's conclusion. The deck dimensions themselves prove nothing, but the book infers that changing deck dimensions mean the shape of the ship's hull changed. It is arguable whether the inference is always valid. W. M. P. Dunne attempted the same basic approach in 1993 and missed the mark. Frigate to Sloop twice admits that ship dimensions recorded years apart by different officers generally may be unreliable (pp. 70, 141) but nevertheless resorts to them several times at key junctures. We cautioned against using recorded dimensions to determine hull form in 1995. See Frigate to Sloop, p. 161; National Intelligencer, 9 April, 10 Sept, 31 Oct, and 28 Nov 1812; "Apple & Orange," pp. 87-93; Dunne, "Clearly No More," p. 80; "Frigate Strikes," pp. 249-50, 256 (n-16); John M. Mason Handbook, Misc. Vol. 138, MC 58.1520, G.W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, CT; James Miller, Journal of USS Erie, 1830-32, MS-2960, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore; William Pearson, "Watch, Quarter Bills, . . . USS Constellation," National Archives RG-45, Entry 406; Craig L. Symonds, Confederate Admiral. The Life and Wars of Franklin Buchanan (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999), pp. 7-12. back to article

Several key pieces of evidence supporting the four-rebuild theory are cited in Frigate to Sloop as having come from the "Leon Polland Papers." The book's scholarly citations regarding the Polland Papers, however, are muddled. In four endnotes (pp. 310-11 [n-21], 320 [n-13], 321 [n-16], 325 [n-65]) and the bibliography (p. 351), the "Leon Polland Papers" are located at the Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy. In two other endnotes (p. 325 [n-64 & 66]), the same papers are located at the National Archives. Reportedly, the papers seen by Frigate to Sloop's author actually are at the Maryland Historical Society. The small collection correctly described as the U.S.F. Constellation Papers MS-1939, at the Maryland Historical Society should not be confused with the several hundred cubic feet of Polland's records we studied in 1989. In December 2002 the complete primary collection we saw was still privately owned. See Fouled Anchors, p. 64 and Frigate to Sloop pp. 137, 143. Also relevant is an e-mail message from Jennifer Bryan, Head, Special Collections & Archives Division, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy, to Thomas Cutler, Senior Acquisitions Editor, Naval Institute Press, 9 Dec 2002, NSWCCD Code 301 Archives. back to article

Although first published in 1966, Chapelle first questioned the 1840 mizzenmast survey in 1970, and we questioned it further in 1992. Without offering evidence to allay suspicions, Frigate to Sloop (p. 313 [n-34]) brands our mistrust as "An attempt . . . to distort the archival evidence...." The earliest found version of the mizzenmast drawing is an old photostatic negative in the primary Polland Papers. See Leon Polland, "Frigate Constellation: An Outline of the Present Restoration," a paper presented to the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers joint meeting, 7 May 1966, pp. 20-1; The Constellation Question, pp. 48-9, 95-6; Fouled Anchors, p. 139; "Apple & Orange," p. 86 (n-27); Frigate to Sloop, pp. 245, 313 (n-34). back to article

Frigate to Sloop links the 1840 ("1829") mizzen mast drawing to another questionable document (See pp. 137, 145, 147, 173, 178 Fig. 7.2, 312 [n-28 & 30]). It is an alleged 1839 drawing by Naval Constructor Francis Grice showing a single transverse half body section of the Constellation. The book struggles mightily to rationalize why Grice, who was stationed at Gosport in 1839, allegedly prepared a drawing of Constellation, which was at Boston. See pp. 145-6.

The Grice drawing was introduced by Evan Randolph in 1992, although it was recognized 27 years earlier. Recently recognized evidence bolsters our 1992 contention that this ridiculous drawing probably is a fake. See Evan Randolph, "Fouled Anchors? Foul Blow," American Neptune, vol. 52, no. 2 (Spring 1992), pp. 94-101; "Query & Response," p. 262. back to article

Similarly, the book attempts to cipher how much a "new" sloop might have cost (pp. 228-30) and deducts from it the cost figure known for the rebuilt sloop. The difference according to the book (26%) represents the savings accrued by using old materials from the frigate. Again, the bottom line is affected by presumptions stacked in favor of the book's conclusion. In the 1950s, 1797 proponent Donald Stewart tried the same "wastage" approach and deduced that 13% of the sloop came from the frigate. Evan Randolph tried the fiscal approach in 1979 and came up with 34%. See Undated, untitled Thermofax, "Donald Stewart, Capt. U.S. Frigate 'Constellation,'" primary Polland Papers; Fouled Anchors, pp. 81-82; Evan Randolph, "U.S.S. Constellation, 1797 to 1979," American Neptune, vol. 39, no. 4 (October 1979), pp. 235-55 (here, p. 245.) "Apple & Orange," p. 91; Canney, Sailing Warships, pp. 160-1. back to article

No naval architect or draftsman has concluded that the 1853 ("1839") frigate hull survey sections match the 1853 sloop design. Frigate to Sloop's author (pp. 251-3) joins Evan Randolph (1979) in contrary assertions. In 1991 and again in 1992 we pointed out that midship sections of all 19th-century U.S. warships were similar in form and deadrise, regardless of the ship-type or size. But when the 1853 ("1839") survey sections are integrated into a three-dimensional data model, it is apparent that the 1853 hull surveys match the 1795 frigate lines and do not match the 1853 sloop design. Frigate to Sloop attempts to link the 1853 ("1839") sections to the sloop, but evades the issue of whether the sections match the 1795 plans for the frigate. Compensating for the recorded age-induced hogging and twisting, we continue to have no doubt that the 1853 hull sections match the Constellation's 1795 lines. Frigate to Sloop dismisses as "simplistic" (p. 341, n-92) our basic, straightforward, two- and three-dimensional, computer-aided naval architectural investigations because, in our 1991 studies, the computer did not consider the first seven chapters of Frigate to Sloop (published in 2002). See The Constellation Question, Fig. 7 (left), p. 29; Fouled Anchors, pp. 143-4; Fig. 8, p. 145; Fig. 17, p. 172; pp. 155-61; "Apple & Orange," p. 86. back to article