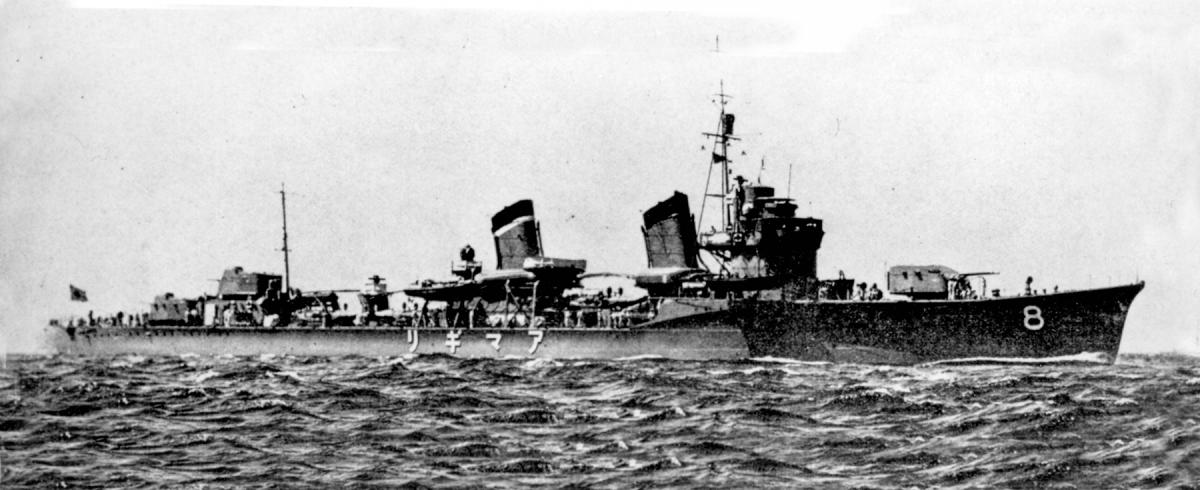

Since the pitch-black night of 1-2 August 1943, when the Japanese destroyer Amagiri rammed and sank the PT-109, debate has flared over precisely what happened. Did John F. Kennedy “allow” the 109 to be rammed because he ran a slack ship and failed to take timely action? Or was he simply in the wrong place at the wrong time?

Testimony from a former tent-mate of JFK’s suggests neither position may account for what really happened that night. Between the lines of that testimony is an even more startling implication: That Kennedy and at least one of his crewmen deliberately may have withheld the truth.

Crisis Situation

Those who have studied this incident generally agree Kennedy had, at most, 10 to 15 seconds in which to react to the sighting of the onrushing Amagiri. Reportedly, he signaled the engine room for full speed and then turned 30° to starboard, toward the destroyer, to present a smaller target and possibly to ready a torpedo counterattack. With so little time, however, the destroyer hit before these measures could take effect. If PT-boat veteran Ted Robinson is to be believed, however, the notion that Kennedy’s emergency response failed because he lacked sufficient time no longer holds much water.

Like Kennedy, Robinson also had lost a boat in the summer of 1943. In a December 1999 article in Naval History, he claimed Kennedy confided in him several weeks after the collision that when he saw the Amagiri bearing down on him his immediate reaction was to throttle up, forgetting in his haste that he had the engines muffled. Kennedy indicated that his failure to “open the flaps” on his mufflers before increasing power resulted in the engines stalling, so that the 109 was effectively adrift when the destroyer sliced into her seconds later.1 This revelation is, to say the least, a potential bombshell.

Did Kennedy panic, forget procedure, and stall his boat, thereby setting it up to be rammed? Should he be, after all, held fully accountable for the loss of the PT-109? In part, that answer depends on the believability of Robinson’s story. Judging from the article, he cherishes his wartime association with the late President, which discounts the possibility that he made up his account to discredit his former tent-mate.2 And on the face of it, his story certainly rings true. It is easy to imagine the green young skipper, seeing his peril, forgetting to open his muffler flaps in his haste to get up his boat’s speed. But the main issue here is not believability. It is historical accuracy. There is an essential problem with Robinson’s statement, that Kennedy told him, “Robbie, I failed to open my flaps.” Namely, it was not Kennedy’s responsibility, or even in his capacity as the skipper, to open the flaps himself.

As on larger ships, the cockpit of a PT boat is connected to the engine room by way of an engine telegraph. When the captain moves the engine throttles he is sending a visual message to the motor machinist’s mate, or “motormac,” sitting by the engines to slow down, speed up, throw the engines into reverse, and so on. The motormac also is responsible for flipping a lever that links to the engine mufflers mounted outside the hull on the transom. This lever opens or closes the butterfly valves of the metal flaps covering the muffler exhaust port. The metal flaps were there to direct the noisy exhaust downward into the water when the boat was going at low speeds, as on patrol. Should the PT need to accelerate, to about 10 knots and over, the motormac had to open the flaps to accommodate the additional exhaust. If he did not do this, he ran the risk that the exhaust would feed back into the engines and stall them.3

This, in effect, is what Kennedy admitted to Robinson as having happened that night. He was patrolling slowly at 6 knots. When he saw the destroyer, he throttled up. On receiving the signal, the motormac first should have opened the muffler flaps. Apparently, he did not do this. Instead, he immediately opened the throttle on the engines and they stalled, leaving the boat helpless before the onrushing bow of the Amagiri.

All this implies that the tragedy was in large measure the motormac’s fault, not Kennedy’s. So why did Kennedy tell Robinson that he himself failed to open the valves, and that he obviously felt terrible about not doing so? The Robinson article makes no attempt to answer these questions or discuss the ramifications of the admission. The article says only that Kennedy was upset about how others “years after the war [sitting] in a nice well-lit room back in Miami Beach” would view the incident, and blamed his failure on the natural disorientation he felt in the midst of the crisis.4

Given all this, Kennedy’s admission of failing to open his flaps makes no sense—until one realizes he is not admitting guilt, but responsibility. Like any sea captain, Kennedy was responsible for everything that happened on his boat. What Kennedy in effect told Robinson is that he was willing to accept that responsibility, at least privately, for what was actually his motormac’s error.5

A Puzzling Mystery

What Kennedy seemed unwilling to do, though, is acknowledge that error in public. After all, a failure on the part of a crewman was ultimately his failure, and, from a personal and official naval standpoint, his blame. Presuming a natural desire on Kennedy’s part to avoid such official censure may help solve a puzzling mystery. It is a mystery posed not only by Kennedy’s alleged confession but also by discrepancies long embedded (and overlooked by scholars, including this one) in the written documentation pertaining to the ramming.

The mystery surrounds the question of whether or not Kennedy throttled up when he first sighted the Amagiri bearing down on him. If he did not signal the engine room for more speed, the motormac would not have been required to open the flaps. No signal therefore meant no failure to open them. No failure to open them meant no blame could be attached to either man for stalling the engines and helping cause the collision. If, on the other hand, Kennedy did signal the engine room for more speed, both men should have had to answer for the motormac’s response. So, did he signal the engine room or not?

The first thing Kennedy should have done on seeing the destroyer was to throttle up. Indeed, for him not to take such an instinctive, self-preserving step defies logic. And later, when critics raised questions about how on-the-ball he and his crew were, Kennedy would have found it advantageous to cite throttling up as an indication he acted decisively at the critical moment. Yet, amazingly, at no time did he ever officially or publicly acknowledge having sent a signal to the engine room to increase speed.

The official Naval Intelligence report of the ramming by Byron White, dated 22 August 1943, says only that Kennedy turned the wheel to starboard to get into a firing position; the report says nothing about his throttling up. Kennedy’s own after-action report also said nothing about calling for more speed. He blandly stated he was unable to “get out of the way of the Jap destroyer . . . because only one of his engines was in gear.” Also, in “Survival,” a June 1944 New Yorker article by John Hersey, Kennedy reported only that he “spun the wheel for an attack but the 109 answered sluggishly.” In 1960-61, when Robert Donovan interviewed him for the book PT-109, Kennedy spoke of turning the wheel but again made no mention of signaling his motormac.6

The mystery deepens. That motormac, Pat “Pappy” McMahon, happens to have supported to the hilt Kennedy’s public version of the event. A Southern California teacher then in his late 30s, McMahon was burned badly in the ramming and was the man whom Kennedy famously spent five hours towing ashore the next day. He appears for the first time in Hersey’s New Yorker article. McMahon told the writer that prior to the collision “he had no idea what was up”—i.e., received no order from the cockpit prior to the collision. Then, in 1960, when Donovan also interviewed McMahon for his book, McMahon again stated he had no warning of danger and was doing only routine engine adjustments when the destroyer struck.7 In other words, he consistently played ignorant of any signal from Kennedy.

Did Kennedy, in fact, not signal the engine room, as both he and McMahon maintained publicly? That seems unlikely. Many writers favorably disposed toward JFK seem to have assumed that he did signal McMahon for more speed, though none has cited the source of such a contention.8 Others not so favorably disposed, including some former PT officers—as they wonder how he could have “allowed” a destroyer to collide with his small, agile PT boat—have suggested that Kennedy erred in running with the engines muffled. They speculate “that when [Kennedy] saw Amagiri he instinctively rammed on full power and the engine (or engines) either coughed severely from exhaust backup or conked out.” One former PT skipper, William Liebenow, even felt that “maybe the motor machinist down below was goofing off. . . . I think that when [Kennedy] made the move with the throttles—if he made a move—they didn’t respond. Nothing happened.”9

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that Kennedy throttled up is that someone very favorably disposed to him actually saw him do it. John Maguire was Kennedy’s radioman, standing right next to the young skipper in the cockpit when the Amagiri loomed out of the darkness. Maguire reported in 1989 that he “turned on keys to fire torpedoes” and that “Kennedy signaled the engine room.” Yet even he professed ignorance about what happened next, adding that, “To this day I don’t know if McMahon signaled the engines.” And apparently, he never bothered to ask.

Gerard Zinser, an engineer, also wrote later that Kennedy throttled up, though he was not standing in the cockpit at the time as Maguire was. Did Zinser actually see Kennedy push the throttles, or did he just read or hear that he did? According to Joan and Clay Blair, the survivor stories were often suspect, since the men had told and retold the same tale so many times they seemed unable to differentiate between what they saw or what they heard or read.

So did Maguire really see Kennedy throttle up? It seems likely he did. He was certainly in a position to do so, and his bafflement over what McMahon did with the signal suggests he did in fact observe it being sent.10

If JFK did throttle up—as Robinson claims he admitted in private and his radioman witnessed in public—and if that was a positive action for him to have taken, why did he not just come out and say so? There has to be a compelling reason, and a desire to avoid blame for McMahon’s error certainly qualifies. In effect, his refusal to admit throttling up saved both men from having to explain what went wrong.

Another Kennedy Conspiracy?

If the above speculation is correct, Kennedy implied, albeit indirectly, that McMahon erred in not opening the flaps, which he felt contributed decisively to the ramming. If it is also true that both Kennedy and McMahon deliberately lied to prevent that error coming to light, the final implication of Robinson’s story is that the two men lied together. Therefore, they conspired.

A fair amount of circumstantial evidence supports such a contention, though naturally such evidence all flows from the above analysis and is dependent on those conclusions. Perhaps the most revealing evidence is that McMahon felt confident enough all those years to repeat the same lie consistently. There was no way he could have felt confident in maintaining that lie unless he knew the man on the other end of that engine telegraph would back him up. Should Kennedy have pressed him officially for an answer as to what happened when he signaled him, claiming ignorance would have done him no good. It was his duty to respond instantly to all such signals, since they could mean the difference between life and death. He would have been required to answer, and the cat would have been out of the bag.

Both certainly would have benefited from the truth being kept quiet. McMahon failed to follow procedure in a crisis situation that probably resulted in the loss of his boat and the deaths of two fellow crewmen. That he would have been disciplined, even court-martialed, is probably a foregone conclusion. For Kennedy, the advantages are also obvious. He genuinely cared about his crew. One possible upside of the decision to keep quiet would be to protect the badly burned McMahon—whom he may have regarded as having made an honest (though nonetheless fatal) mistake—from the wrath of the Navy and, perhaps more important, from his fellow shipmates. On a more selfish level, though, Kennedy knew he was ultimately responsible if a crewman erred under his command, and it could have resulted in disciplinary action.

Whatever the official Navy reaction, Kennedy no doubt would have been especially dogged by such a poor showing. Perhaps a permanent stain on his service record would have been no big deal if he planned on being an electrician, but even then he had hopes of going into politics, possibly of even rising to become President. Keeping McMahon’s failure a secret therefore would have been extremely important.

This does not, of course, prove such a conspiracy existed. What is needed now is some additional hard evidence that has eluded researchers to this day.11 One thing is certain: the debate over JFK’s actions (and McMahon’s) will continue. It is hoped this analysis will help broaden the scope of that inquiry into the elusive truth of what really happened that night, and why.

1. Rich Pedroncelli, “JFK: A PT Skipper Remembers,” Naval History, December 1999, p. 27. This is not the first time Mr. Robinson has come forward with his story, but evidently, its ramifications have not been explored adequately by researchers or scholars.

2. Pedroncelli, pp. 24-27.

3. Conversation with Alyce Guthrie of PT Boats, Inc., 16 July 2001, after she consulted with several veteran motormacs about the technical aspects of muffler flap operation. See also Dick Keresey, PT-105 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), p. 79, for a revealing discussion of these flaps.

4. Pedroncelli, pp. 26-27.

5. It is unclear if Ted Robinson appreciates the full implications here. As of this writing, he is believed to be at work on his own book on PT-109 and is therefore not talking to outside researchers about his experiences.

6. See the official report, “Sinking of PT 109 and subsequent rescue of survivors,” prepared 22 August 1943 by Lt. (j.g.) J. C. McClure, USNR, and Lt. (j.g.) Byron R. White, USNR, Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla One intelligence officers, Naval Historical Center, Washington D.C. Extract from Kennedy’s after action report is found in the official Flotilla One newsletter, Mosquito Bites, dated 15 September 1943, quoted in Joan and Clay Blair Jr., The Search for J.F.K. (New York: Berkley Publishing Corporation, 1976) p. 272. See John Hersey, “Survival,” The New Yorker, 17 June 1944, reprinted in The New Yorker Book of War Pieces: London, 1939 to Hiroshima, 1945 (New York: Schocken Books, 1988), p. 292. See also Robert Donovan, PT 109: John F. Kennedy in World War II (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961), p. 144, on Kennedy only acknowledging turning the wheel, not throttling up the engines.

7. Hersey, p. 293. See also Donovan, p. 145.

8. Richard Tregaskis, John F. Kennedy: War Hero (New York: Dell, 1962), p. 158; Chandler Whipple, Lt. John F. Kennedy-Expendable! (New York: Nova Books, 1964), p. 104.

9. Joan and Clay Blair Jr., pp. 271-72.

10. Wil Haygood, “3 Men and the JFK Legend: Survivor Recalls Night of Tragedy, Heroism,” The Boston Globe, 21 June 1989. See Joan and Clay Blair Jr., p. 246.

11. In spring 2002 Robert Ballard located what appeared to be the partial remains of the 109’s engine room in 1,300 feet of water. The engine room was reportedly covered by sand dunes. Since the Navy does not allow such wrecks to be exploited, and since Ballard had “an understanding” with the Kennedy family to “not disturb the site or dig it up,” it is unlikely there will be any attempt to answer these questions by examining the remains. Guy Gugliotta, “Ballard Announces His Discovery of Kennedy’s PT-109,” The Washington Post, 11 July 2002, p. A03.