He is the author of the revised and newly released Command of the Seas (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001) and On Seas of Glory (New York: The Free Press, 2001). Ronald Reagan's first Secretary of the Navy talked recently at U.S. Naval Institute headquarters with Naval History Editor Fred L. Schultz about his books and his public service. For his thoughts on the current state of military affairs and the ongoing operations in Afghanistan, see the December 2001 issue of the Naval Institute's Proceedings magazine.

Naval History: What made you decide to write books?

Lehman: When I finished my tour as Secretary of the Navy, I wanted to set down my thoughts and lessons learned while they were still fresh, so I could put them on a shelf and get on with the rest of my life. It was great therapy.

Unfortunately, some of the thoughts were perhaps a bit too fresh. In rereading Command of the Seas, for instance, I found that some things I said in it were a bit overwrought and, in some cases, wrong. These cases were very few, I can assure you. [Laughter] The reissued edition has fine-tuned it, from a perspective of almost 15 years. I've updated and added an afterword for every section. And I still think it holds up pretty well.

Based on my experience in government, the lessons in this book proved to me that a few people with a clear agenda can make a huge difference in government and the course of history. In the Reagan administration, we were able to accomplish a great deal. Winning the Cold War is not a bad accomplishment, in a historical context. It all started with President Ronald Reagan, but really it was the spirit of the times. People throughout the government were captivated by the American spirit to do something different, to change the direction of the country.

Naval History: What set the Reagan administration apart?

Lehman: We had so many first-class people at all levels, especially from my perspective in the Pentagon. The people in the Navy and Marine Corps in particular responded instantly to the leadership from President Reagan and all the people in the national security hierarchy. They had a sense of purpose, a sense of a reassertion of the vision and the real mission of the United States in the course of world history.

This wasn't just politics as usual. This went for everyone, from the deckplates to the bureaucracy, at every level. I've come to appreciate this even more after having been back in the business world for 13 years. I've spent a fair bit of time with some of the best financial business leaders and professional leaders in the world, and I think our people throughout the Navy and Marine Corps—all the services, actually—stack up well in terms of quality, productivity, and motivation. In fact, they're even better on the motivation factor, because they have a sense of duty, honor, and country. They recognize leadership and respond to it better, and they are even more efficient and effective in producing results than typical people in the business world. That's the central lesson I wanted to get across. The U.S. military, particularly the naval services, have played a unique role throughout our history. The media and the Congress tend to focus on hardware issues. But a cultural wisdom, the accumulation and distillation of 250 years, is what has been most important in charting the direction of our country. It's still very much alive, and it manifests itself in so many different ways. This is what I tried to capture in Command of the Seas—how, in the hurly-burly of the political debates and crises, naval virtues played a major role.

Naval History: What can we learn from these books?

Lehman: I think both books provide lessons for today, including how to deal with terrorism. I go into some detail on the tragedy we suffered in Beirut in 1983, when we lost 241 Marines. We knew who they were, and we knew where they were. And the Navy put together a forceful and precise retaliation plan, which the President endorsed. But both books also recount how we sat by and watched the bureaucracy, in the larger sense, defeat and thwart that response to terrorism. Nothing ever was done. We did launch an air strike almost three months later, but that was really in response to the firing of a missile, which was a kind of subterfuge. It was a botched air strike almost as bad as [President] Bill Clinton's lobbing a few cruise missiles at meaningless targets. It just strengthened the terrorists' belief that we didn't have the guts to take them on, that we would do things only by remote control and didn't even have the capability to hit valuable targets. The people who planned that massacre are still, today, planning other massacres, again still supported and trained by Iran and equipped out of the K-Mart of terrorism in Iraq. Clearly, we failed to learn that lesson.

Another story I recount in different ways in both books is the 1985 hijacking by Muslim extremists of the cruise ship Achille Lauro and the murder of the New Yorker on board [Leon Klinghoffer]. I tell about the brilliant job done by the Sixth Fleet—under [Admirals] Frank Kelso and Dave Jeremiah, and run from the White House by Ollie North and John Poindexter—that effectively intercepted those terrorists. The government of Egypt first gave them safe haven, then allowed them to escape. They were intercepted in a brilliant move over the Mediterranean and forced to land in Italy. We had arranged to have the special forces plane literally right behind them on the runway. And we surrounded the plane.

Then the government of Italy, having had a kind of protection deal with the terrorists, surrounded our guys and made them turn over their prisoners. Then the Italians released them quietly. They had an agreement that it was okay to kill Americans, but no acts of terrorism could take place on Italian soil. In return, the Italians agreed to look the other way. That is a system that has grown over the last 20 years, particularly in the so-called friendly Arab world, but also among many of our allies in Europe.

For 25 years, we have our own record of contributing to building the international terrorist network by not having the resolve to retaliate effectively and to cut off the tacit support by our friends. The flow of money has turned into an international mafia of protection funds paid by Saudi "foundations" and sources from the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. So this wake-up call has been a long time in coming. Sadly, it has come at a huge cost in lives and treasure.

Naval History: How did the idea for a book like On Seas of Glory germinate?

Lehman: My interest began when I was sitting around the dinner table, hearing stories that my dad would tell about his grandfather, who was in the Civil War Navy; and his grandfather's great grandfather, who was a privateer in the American Revolution. A few times, although he spoke rarely about it, he recalled his own adventures in the Navy. I've always been fascinated, obviously, with naval history. But more important, I developed an appreciation for naval people.

Sending people out in little wooden or steel containers for three or four years at a time creates a unique culture. And that has, in turn, fed into every part of our civilization. I focused on three broad categories of people—the courageous swashbucklers, the great leaders, and the common sailors—and the contributions they've made over the past 250 years. I wrote about John Paul Jones and Stephen Decatur, the guys who stormed the mouths of cannon and jumped aboard and took over ships. They lived for the glory and for the right motivations. They were exciting, and they've made for some great movies. It's important to be truthful about why they are heroes but not gloss over their idiosyncrasies. For instance, John Paul Jones was probably clinically committable. But that takes away nothing from the fact that he was great hero. His is a very identifiable type.

And then there are the equally courageous but much steadier leaders in naval history: people like John Barry, who I think was probably the greatest naval leader of the American Revolution; people like our own Jim Holloway [former Chief of Naval Operations] and James Forrestal [first Secretary of Defense]. They didn't have the flash, perhaps, of the John Paul Joneses, but they made huge contributions, many of them unknown.

The third category of people, the citizen-sailors, are rarely written about. These were the landsmen or yachtsmen who rallied to the colors and served brilliantly and courageously in time of war, then went home to their Wall Street yachts or their farms. This is a great tradition of our naval power that most other navies do not share.

I also wanted to give readers a flavor of the different types of ships that have contributed to our naval history—the super frigates, like the Constitution, the Iowa (BB-61)-class battleships, or the Civil War Commodore-class gunboats. Sailors have very different relationships with their ships than soldiers have with their tanks or Air Force people have with their fighters. For one thing, ships last a lot longer. They embody a long history, including craftsmanship and design philosophy.

Ultimately, of course I wrote about battles that have interested me, ones in which the sailors and their ships came together to do what they were designed to do. Again, my choices of people, ships, and battles are entirely the result of my own quirks. These stories are not put forward as a canon of who should be the greats in any of these three categories. They are simply the ones that interest me the most, and I hope they interest readers.

Naval History: How did your research progress?

Lehman: I tried to be meticulous in providing historical context. I had six people working for me on a freelance basis. These were the people who did the real digging in the archives. Then I was able to con the Naval Historical Center into agreeing to be my fact checker. The historians there made quite a few improvements, shall we say, to all of the text. I was amazed, in the research, to find how different authoritative accounts are in what happened on different dates and which ship was where. It really shouldn't be surprising, because everything was written after the fact. And in the fog of battle, people don't keep exact notes of whether it was the port quarter or the starboard quarter and that sort of thing.

This book was great fun. It was wonderful to delve into the lives of many of these people and to go into the original records. Some of the most moving were the actual records of the prison hulks from the British records in Greenwich, the firsthand accounts of American sailors who were in hulks in what is now the Brooklyn Navy Yard. These stories are largely untold. Everybody's heard about the hulks there, but few realize 11,000 sailors and soldiers died there. More than twice the number killed on the battlefield in the entire war died in those hulks.

The one big difference I had with the Naval Historical Center was on the importance of privateers. I was struck years ago, right after I left the Navy, when I was serving on a board in London and was able to spend some time in the archives of Lloyd's. That's where I first learned about American privateers, who have been basically ignored in all the official naval canons. Naval people always tended to look at privateers in the 19th century as pirates who were out for getting rich and would run from a fight.

There was something to that, because their purpose was not to get in fights with British frigates, but to grab British merchantmen and get prize money. But the fact is—the librarian showed me the logs—3,000 British merchantmen were captured during the American Revolution. That was 15% of the entire British merchant fleet. And they were all insured at Lloyd's, which bankrupted many wealthy members of Parliament. The work of those privateers produced the famous petition to George III after Yorktown, demanding that he stop the war or else. Military and naval historians tend to look at military and naval things and ignore the economic factors.

I failed, I'm afraid, to convince the Naval Historical Center that the privateers won the war, and not John Paul Jones. But the truth probably lies somewhere in between. So it's an opinionated book, for sure. It is unapologetically a very subjective view of people and battles. Some of the people I like and some of them I don't like. It's not hard to tell them apart. The purpose was to put in a readable and accessible form, for the general reader, an insight into what makes naval culture unique and how much it has been woven into the development of our country's institutions. I hope I've succeeded. I think the Free Press did a great job in publishing it; not as good as the Naval Institute does on its books, but still not bad.

Naval History: It seems as though On Seas of Glory is actually two books. One is third person and another is first person. How did you make those fit?

Lehman: It's not meant to be autobiographical, and it isn't. The only part where I talk about myself is in a chapter on the 600-ship Navy. But you will find other Lehmans scattered through the text.

Naval History: No matter who writes it, naval history by definition almost has to be about blue-water operations and conventional war. Why is that, and is it the wave of the future?

Lehman: This book recounts a history that is not really blue-water over brown-water. The Civil War was a brown-water war. And the Navy played an enormous role. It was a 600-ship Navy that ended up with 700 ships. And it was manned at about the same ratio as in World War II—70 reservists to 1 regular. And Vietnam, of course, was not a blue-water war.

While [Alfred Thayer] Mahan gives us the great blue-water tradition and perspective, which is important for maintaining the global reach we have, the actual application of power has rarely taken place on blue water. If you took Jack Sweetman's great Naval Institute chronology, American Naval History, and totaled all the naval conflicts in it, you'd probably find low single digits were actually in blue water. You have to go through a lot of blue water to get to Afghanistan, but this is not, obviously, a blue-water operation. I see more of the same in the future.

Yes, you have to be able to command blue-water areas, because Army transports, fast-deployment ships, and pre-positioned ships have to go through blue water. And as we know, 95% of all tonnage—military and civilian—still has to go by sea and always will.

It used to be said that the British Army was simply a projectile to be fired ashore by the Royal Navy. In the future, that is still going to be a major naval role, to fire ashore Army special forces; or do what we did in Haiti—fire ashore the 10th Mountain Division, support them, and provide air cover and close air support.

So I don't think the next 100 years is going to be much different in that respect from the last 250. Obviously, technology will be different, but the geography is still the same around the world. And our interests are even more entwined in many different ways. Yes, there's a revolution in technology, but there's no revolution in military affairs, as such.

Naval History: How important is naval history—small "n," small "h?"

Lehman: First of all, I think Naval History magazine is a fabulous, relatively new, addition to the literature. It's the best in its field, without question. And I think the readership is going to continue to grow.

I truly believe the only thing new in the world is the history you don't know, as Harry Truman said. I wish I had had more time to delve into naval history before I was Secretary of the Navy. You do draw wisdom from other people's experiences. One of the things I address in my new book is the elitism of the Navy. And to understand its roots gives you a new appreciation of how it has evolved. Thomas Jefferson opposed the establishment of a navy because he said it was bound to become an aristocratic and elitist force that would drag us into international wars. And he was right. The Navy did become very aristocratic, very elitist, and very snobbish.

From the founding of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1845 until after World War I, only 1% of midshipmen admitted to the Naval Academy came from working-class backgrounds. The other 99% were from families of college-educated professionals. The Academy didn't want the working classes. These were gentlemen. It's no accident that the New York Yacht Club has a naval membership, because they were all part of the club. And it's no accident that naval aviation started as the Yale Flying Club.

The Navy always has been part of the eastern establishment; that's where its roots were, through World War II. If you look at the list of naval aviators who flew in the first years of World War II, you won't find a single Jewish or Hispanic name, and there are no names that end with vowels. They were all white, Anglo-Saxon names. That's just the way it was. Look at the pictures.

The Army and the Marine Corps always have had a very different tradition, which continued through World War II. In those services, 60% of the officers who served in World War II were promoted from the enlisted ranks—battlefield promotions. They actively looked to fill their officer corps from promising young enlisted men, and they'd pull them out and send them to officer candidate school. The Navy absolutely refused to do that. Only 2% of the officers who served in the Navy in World War II had prior enlisted service. The Navy wanted only university graduates as officers. And that's why the Navy had the V-12 and the Holloway programs. They wanted to draw on Harvard, Yale, Penn, Cal Tech, and Stanford. And that's one of the reasons the Navy was so late in racial reform. That tradition of elitism had other unpleasant sides, anti-Semitism and snobbery being two of them.

Today, the elitism is of a different kind. The Army and the Air Force have a democratic, egalitarian kind of culture, and the Navy does not. Particularly since [former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo] Zumwalt's time, it is an elitism of merit. Today, people in the Navy don't care about ethnic background, religion, or race. They care about accomplishment and personal excellence, not where you came from or how you got there.

Naval History: Let's talk about John Lehman. What do you consider your crowning achievement in public service, what was your biggest regret, and what would you do differently if you could?

Lehman: Those are interesting questions. I think my proudest achievement was not necessarily bringing back leather jackets and brown shoes—as some people would think—but restoring a sense of direction, mission, morale, and eliteness to the naval services. I think that was important. I happened to be in the right place at the right time under a President who truly believed in that. He believed in it for all the services, and I got to be the transmitter for the naval services.

This is one reason I wrote this latest book. I think it's important that naval people be reminded of the roots of their values and their culture. The nation depends on strong naval leadership, and I think that's my proudest accomplishment.

The greatest regret, I guess, is that I made a lot of mistakes. I probably wasted too many of the Navy's chips on fighting the Goldwater-Nichols Act. Not that it shouldn't have been fought, but there are some battles where you've got to recognize the tide is running too strong against you. I think both [Secretary of Defense Caspar] Weinberger and I kind of used up a little too much credibility.

In a similar vein, I got into a stupid, counterproductive fight over the promotion board—if you'll recall—in the last few months I was there. Again, I still believe the issue was right, but I don't think it helped the Navy having that kind of a public fight. I think that was a mistake.

And there are things I would have done differently. I wish I had known, for instance, that as soon as I left, OSD [the Office of the Secretary of Defense] would triumph and cancel both the A-6 and the A-12 [attack aircraft]. We'd been defeating them for six years, trying to keep the Navy in the deep-strike mission. What I should have done was an option we considered, which was to make the F-14 Tomcat basically into a strike Eagle, an F-15E. Instead of going with an A-6F and an F-14D, we should have gone with basically what they've got on the cheap now, which is a dual-mission aircraft like the F-15E. We could have made a better F-14, too, but that kind of gets into the nits.

I guess the biggest regret I have is that I was unable to institutionalize, as much as I would have liked, better discipline in procurement. We had a shipbuilding meeting every other Friday and a regular aircraft and missile review. Once a program finally was approved for production, no one could make engineering changes without the signature of both the Secretary of the Navy and the Secretary of Defense. That kept the prices of aircraft down. We did only block upgrades. This culture faded right after I left. But that's the only way you can get control of tremendous cost creeps. If you let the bureaucracy do it, every bell and whistle will be attached, which is understandable. That's not a criticism. That's just the way it works.

We were a little naive in thinking we could change the acquisition and personnel cultures permanently. The green-eyeshade guys came forward, trying to lengthen the committed service, particularly for aviators. It was five years, I think, when I was there. I wouldn't let them do it, because I felt it was phony. They kept saying, "It costs $20 million to train an aviator." That's baloney. You have to keep a training base for mobilization purposes anyway. And so there's nothing wrong with putting more than you need through that base, to keep it warm. Now, we're not attracting the same kind of people, in my judgment, by having the current ten-year obligation.

I tried integrate the reserves more with the fleet and to attract more people who were not prepared to sign up for ten-year obligations. The plan was for them to come in for a two-year obligation and then drill for six, on active-reserve drill. And many of them, of course, would find they liked it once they got in. But before they got in, they would never sign up for ten years. That's common sense, it seems to me. But all that disappeared; now we've got ten-year obligations and nobody from the northeast can get into the Navy anymore.

What was the last part of the question?

Naval History: What you would have done differently?

Lehman: I would have picked fewer fights, for one thing. [Laughter] I had some good fights for the right reasons, and I'm glad we took them on. In retrospect, I had some counterproductive fights over people and policy issues that weren't worth burning the candle. I would pick my fights a little more judiciously next time.

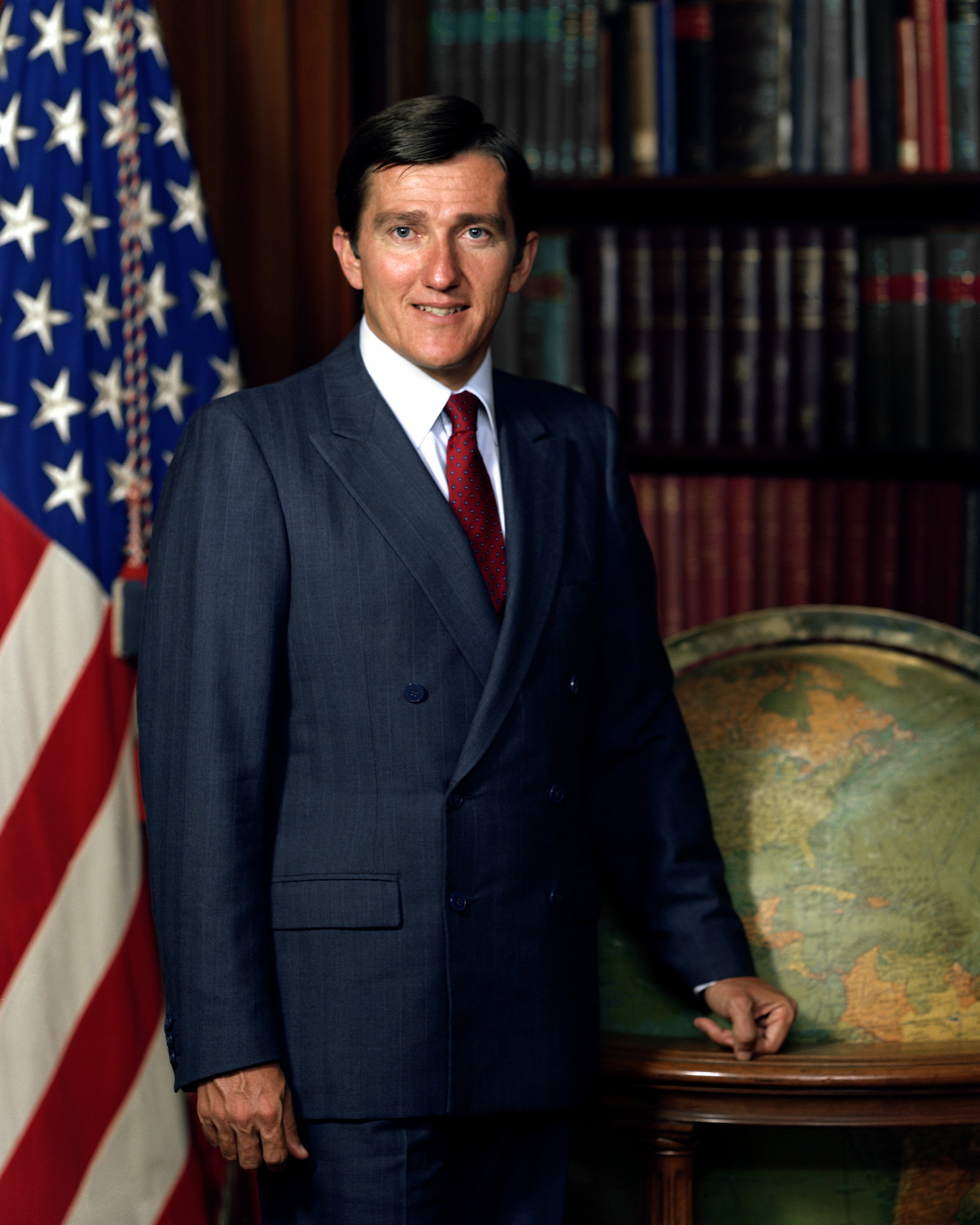

'Captivated by the American Spirit'

President Ronald Reagans first Secretary of the Navy reflects on the importance of naval history and highlights of his public service career.

An Interview with John Lehman