In July 1964, Operational Plan 34A was taking off, but during the first six months of this highly classified program of covert attacks against North Vietnam, one after the other, missions failed, often spelling doom for the commando teams inserted into the North by boat and parachute.

These secret intelligence-gathering missions and sabotage operations had begun under the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1961, but in January 1964, the program was transferred to the Defense Department under the control of a cover organization called the Studies and Observations Group (SOG). For the maritime part of the covert operation, Nasty-class fast patrol boats were purchased quietly from Norway to lend the illusion that the United States was not involved in the operations.

To increase the chances of success, SOG proposed increased raids along the coast, emphasizing offshore bombardment by the boats rather than inserting commandos. In Saigon, General William C. Westmoreland, the new commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), approved of the plan, and SOG began testing 81-mm mortars, 4.5-inch rockets, and recoilless rifles aboard the boats. On 30 July, Westmoreland revised the 34A maritime operations schedule for August, increasing the number of raids by "283% over the July program and 566% over June."1 Most of these would be shore bombardment.

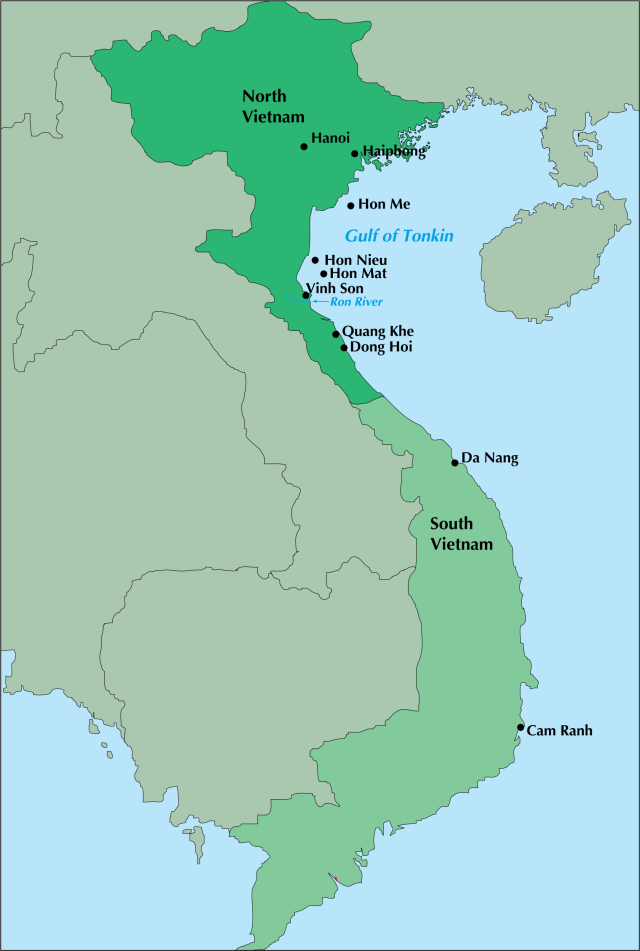

That very night, the idea was put to the test. Under cover of darkness, four boats (PTF-2, PTF-3, PTF-5, and PTF-6) left Da Nang, racing north up the coast toward the demilitarized zone (DMZ), then angling farther out to sea as they left the safety of South Vietnamese waters.2 About five hours later they neared their objective: the offshore islands of Hon Me and Hon Nieu.

Just before midnight, the four boats cut their engines. To the northwest, though they could not see it in the blackness, was Hon Me; to the southwest lay Hon Nieu. The crews quietly made last-minute plans, then split up. It was 20 minutes into the new day, 31 July, when PTF-3 and PTF-6, both under the command of Lieutenant Son—considered one of the best boat skippers in the covert fleet—reached Hon Me and began their run at the shore. Even in the darkness, the commandos could see their target—a water tower surrounded by a few military buildings.

Suddenly, North Vietnamese guns opened fire from the shore. Heavy machine-gun bullets riddled PTF-6, tearing away part of the port bow and wounding four South Vietnamese crewmen, including Lieutenant Son. Moments later, one of the crewmen spotted a North Vietnamese Swatow patrol boat bearing down on them. There was no way to get a commando team ashore to plant demolition charges; they would have do what damage they could with the boats’ guns.3

Illumination rounds shot skyward, catching the patrol boats in their harsh glare. But the light helped the commandos as well, revealing their targets. Holding their vector despite the gunfire, the boats rushed in, pouring 20-mm and 40-mm fire and 57-mm recoilless rifle rounds into their target. In less than 25 minutes, the attack was over. PTF-3 and PTF-6 broke off and streaked south for safety; they were back in port before 1200.

At Hon Nieu, the attack was a complete surprise. Just after midnight on 31 July, PTF-2 and PTF-5, commanded by Lieutenant Huyet, arrived undetected at a position 800 yards northeast of the island. Moving in closer, the crew could see their target—a communications tower—silhouetted in the moonlight. Both boats opened fire, scoring hits on the tower, then moved on to other buildings nearby. The only opposition came from a few scattered machine guns on shore, but they did no damage. Forty-five minutes after beginning their attack, the commandos withdrew. The two boats headed northeast along the same route they had come, then turned south for the run back to South Vietnam.

North Vietnam Reacts

Within days, Hanoi lodged a complaint with the International Control Commission (ICC), which had been established in 1954 to oversee the provisions of the Geneva Accords. The United States denied involvement. In response, the North Vietnamese built up their naval presence around the offshore islands. On 3 August, the CIA confirmed that "Hanoi’s naval units have displayed increasing sensitivity to U.S. and South Vietnamese naval activity in the Gulf of Tonkin during the past several months."4

At about the same time, there were other "secret" missions going on. Codenamed Desoto, they were special U.S. Navy patrols designed to eavesdrop on enemy shore-based communications—specifically China, North Korea, and now North Vietnam. Typically, the missions were carried out by a destroyer specially outfitted with sensitive eavesdropping equipment.

Until 1964, Desoto patrols stayed at least 20 miles away from the coast. But on 7 January, the Seventh Fleet eased the restriction, allowing the destroyers to approach to within four miles—still one mile beyond North Vietnamese territorial waters as recognized by the United States. The first such Desoto mission was conducted off the North Vietnamese coast in February 1964, followed by more through the spring. In July, General Westmoreland asked that Desoto patrols be expanded to cover 34A missions from Vinh Son north to the islands of Hon Me, Hon Nieu, and Hon Mat, all of which housed North Vietnamese radar installations or other coastwatching equipment. The stakes were high because Hanoi had beefed up its southern coastal defenses by adding four new Swatow gunboats at Quang Khe, a naval base 75 miles north of the DMZ, and ten more just to the south at Dong Hoi.

Because the North Vietnamese had fewer than 50 Swatows, most of them up north near the important industrial port of Haiphong, the movement south of one-third of its fleet was strong evidence that 34A and the Desoto patrols were concerning Hanoi. Westmoreland reported that although he was not absolutely certain why the Swatows were shifted south, the move "could be attributable to recent successful [34A] operations."5

In reality there was little actual coordination between 34A and Desoto. During May, Admiral U. S. G. Sharp, the Pacific Fleet Commander-in-Chief, had suggested that 34A raids could be coordinated "with the operation of a shipboard radar to reduce the possibility of North Vietnamese radar detection of the delivery vehicle." The Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, Admiral Harry D. Felt, agreed and suggested that a U.S. Navy ship could be used to vector 34A boats to their targets.6

The lack of success in SOG’s missions during the first few months of 1964 made this proposal quite attractive. But by the end of June, the situation had changed. Covert maritime operations were in full swing, and some of the missions succeeded in blowing up small installations along the coast, leading General Westmoreland to conclude that any close connection between 34A and Desoto would destroy the thin veneer of deniability surrounding the operations. In the end the Navy agreed, and in concert with MACV, took steps to ensure that "34A operations will be adjusted to prevent interference" with Desoto patrols.7 This did not mean that MACV did not welcome the information brought back by the Desoto patrols, only that the two missions would not actively support one another.

The Maddox Heads North

On 28 July, the latest specially fitted destroyer, the Maddox (DD-731), set out from Taiwan for the South China Sea. Three days later, she rendezvoused with a tanker just east of the DMZ before beginning her intelligence- gathering mission up the North Vietnamese coast. The Maddox planned to sail to 16 points along the North Vietnam coast, ranging from the DMZ north to the Chinese border. At each point, the ship would stop and circle, picking up electronic signals before moving on. Everything went smoothly until the early hours of 2 August, when intelligence picked up indications that the North Vietnamese Navy had moved additional Swatows into the vicinity of Hon Me and Hon Nieu Islands and ordered them to prepare for battle. This was almost certainly a reaction to the recent 34A raids.

At 0354 on 2 August, the destroyer was just south of Hon Me Island. Captain John J. Herrick, Commander Destroyer Division 192, embarked in the Maddox, concluded that there would be "possible hostile action." He headed seaward hoping to avoid a confrontation until daybreak, then returned to the coast at 1045, this time north of Hon Me. It is difficult to imagine that the North Vietnamese could come to any other conclusion than that the 34A and Desoto missions were all part of the same operation.

The Maddox was attacked at 1600. Ship’s radar detected five patrol boats, which turned out to be P-4 torpedo boats and Swatows. When the enemy boats closed to less than 10,000 yards, the destroyer fired three shots across the bow of the lead vessel. In response, the North Vietnamese boat launched a torpedo. The Maddox fired again—this time to kill—hitting the second North Vietnamese boat just as it launched two torpedoes. Badly damaged, the boat limped home. Changing course in time to evade the torpedoes, the Maddox again was attacked, this time by a boat that fired another torpedo and 14.5-mm machine guns. The bullets struck the destroyer; the torpedo missed. As the enemy boat passed astern, it was raked by gunfire from the Maddox that killed the boat’s commander.

The battle was over in 22 minutes. The North Vietnamese turned for shore with the Maddox in pursuit. Aircraft from the Ticonderoga (CVA-14) appeared on the scene, strafing three torpedo boats and sinking the one that had been damaged in the battle with the Maddox.

The Desoto patrol continued with another destroyer, the Turner Joy (DD-951), coming along to ward off further trouble. On the night of 4 August, both ships reported renewed attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats. Today, it is believed that this second attack did not occur and was merely reports from jittery radar and sonar operators, but at the time it was taken as evidence that Hanoi was raising the stakes against the United States.

As far as the headlines were concerned, that was it, but the covert campaign continued unabated. During the afternoon of 3 August, another maritime team headed north from Da Nang. Four boats, PTF-1, PTF-2 (the American-made patrol boats), PTF-5, and PTF-6 (Nasty boats), were on their way to bombard a North Vietnamese radar installation at Vinh Son and a security post on the banks of the nearby Ron River, both about 90 miles north of the DMZ. Each boat carried a 16-man crew and a 57-mm recoilless rifle, plus machine guns. PTF-2 had mechanical troubles and had to turn back, but the other boats made it to their rendezvous point off the coast from Vinh Son. PTF-1 and PTF-5 raced toward shore. For 25 minutes the boats fired on the radar station, then headed back to Da Nang.

PTF-6 took up station at the mouth of the Ron River, lit up the sky with illumination rounds, and fired at the security post. The rounds set some of the buildings ablaze, keeping the defenders off balance. Scattered small-arms sent tracers toward the commandos, but no one was hurt. Just after midnight on 4 August, PTF-6 turned for home, pursued by an enemy Swatow. Easily outdistancing the North Vietnamese boat, the commandos arrived back at Da Nang shortly after daybreak.8

Making the Connection

North Vietnam immediately and publicly linked the 34A raids and the Desoto patrol, a move that threatened tentative peace feelers from Washington that were only just reaching Hanoi. The Johnson administration had made the first of several secret diplomatic attempts during the summer of 1964 to convince the North Vietnamese to stop its war on South Vietnam, using the chief Canadian delegate to the ICC, J. Blair Seaborn, to pass the message along to Hanoi. After the Tonkin Gulf incident, the State Department cabled Seaborn, instructing him to tell the North Vietnamese that "neither the Maddox or any other destroyer was in any way associated with any attack on the DRV [Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam] islands." This was the first of several carefully worded official statements aimed at separating 34A and Desoto and leaving the impression that the United States was not involved in the covert operations.9

The U.S. Navy stressed that the two technically were not in communication with one another, but the distinction was irrelevant to the North Vietnamese. Both were perceived as threats, and both were in the same general area at about the same time.

CIA Director John McCone was convinced that Hanoi was reacting to the raids when it attacked the Maddox. During a meeting at the White House on the evening of 4 August, President Johnson asked McCone, "Do they want a war by attacking our ships in the middle of the Gulf of Tonkin?"

"No," replied McCone. "The North Vietnamese are reacting defensively to our attacks on their offshore islands. . . . The attack is a signal to us that the North Vietnamese have the will and determination to continue the war." It took only a little imagination to see why the North Vietnamese might connect the two. In this case, perception was much more important than reality.10

The North Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs made all this clear in September when it published a "Memorandum Regarding the U.S. War Acts Against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the First Days of August 1964." Hanoi pointed out what Washington denied: "On July 30, 1964 . . . U.S. and South Vietnamese warships intruded into the territorial waters of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and simultaneously shelled: Hon Nieu Island, 4 kilometers off the coast of Thanh Hoa Province [and] Hon Me Island, 12 kilometers off the coast of Thanh Hoa Province." It also outlined the Maddox’s path along the coast on 2 August and the 34A attacks on Vinh Son the following day. Hanoi denied the charge that it had fired on the U.S. destroyers on 4 August, calling the charge "an impudent fabrication."11

SOG took the mounting war of words very seriously and assumed the worst—that an investigation would expose its operations against the North. Both South Vietnamese and U.S. maritime operators in Da Nang assumed that their raids were the cause of the mounting international crisis, and they never for a moment doubted that the North Vietnamese believed that the raids and the Desoto patrols were one and the same. And it didn’t take much detective work to figure out where the commandos were stationed. The only solution was to get rid of the evidence.

A U.S. Navy SEAL (Sea Air Land) team officer assigned to the SOG maritime operations training staff, Lieutenant James Hawes, led the covert boat fleet out of Da Nang and down the coast 300 miles to Cam Ranh Bay, where they waited out the crisis in isolation. U.S. soldiers recall Cam Ranh as a sprawling logistic center for materiel bolstering the war effort, but in the summer of 1964 it was only a junk force training base near a village of farmers and fishermen. Until the ICC investigation blew over a week later, the commandos camped on a small pier. Then they boarded their boats and headed back to Da Nang.12

At the White House, administration officials panicked as the public spotlight illuminated their policy in Vietnam and threatened to reveal its covert roots. President Johnson ordered a halt to all 34A operations "to avoid sending confusing signals associated with recent events in the Gulf of Tonkin." If there had been any doubt before about whose hand was behind the raids, surely there was none now.

In Saigon, Ambassador Maxwell Taylor objected to the halt, saying that "it is my conviction that we must resume these operations and continue their pressure on North Vietnam as soon as possible, leaving no impression that we or the South Vietnamese have been deterred from our operations because of the Tonkin Gulf incidents." But the administration dithered, informing the embassy only that "further OPLAN 34A operations should be held off pending review of the situation in Washington."13 As far as the State Department was concerned, there was no need to "review" the operations. "We believe that present OPLAN 34A activities are beginning to rattle Hanoi," wrote Secretary of State Dean Rusk, "and [the] Maddox incident is directly related to their effort to resist these activities. We have no intention of yielding to pressure."14

Congress Reacts

Of course, none of this was known to Congress, which demanded an explanation for the goings-on in the Tonkin Gulf. On 6 August, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara told a joint session of the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees that the North Vietnamese attack on the Maddox was ". . . no isolated event. They are part and parcel of a continuing Communist drive to conquer South Vietnam. . . ." McNamara did not mention the 34A raids.15

Senator Wayne Morse (D-OR) challenged the account, and argued that despite evidence that 34A missions and Desoto patrols were not operating in tandem, Hanoi could only have concluded that they were. But Morse did not know enough about the program to ask pointed questions. "I think we are kidding the world if you try to give the impression that when the South Vietnamese naval boats bombarded two islands a short distance off the coast of North Vietnam we were not implicated," he scornfully told McNamara during the hearings.16

McNamara took advantage of Morse’s imprecision and concentrated on the senator’s connection between 34A and Desoto, squirming away from the issue of U.S. involvement in covert missions by claiming that the Maddox "was not informed of, was not aware [of], had no evidence of, and so far as I know today had no knowledge of any possible South Vietnamese actions in connection with the two islands Senator Morse referred to." Although McNamara did not know it at the time, part of his statement was not true; Captain Herrick, the Desoto patrol commander, did know about the 34A raids, something that his ship’s logs later made clear. And, of course, McNamara himself knew about the "South Vietnamese actions in connection with the two islands," but his cautiously worded answer got him out of admitting it.

The fig leaf of plausible denial served McNamara in this case, but it was scant cover. Hanoi was more than willing to tell the world about the attacks, and it took either a fool or an innocent to believe that the United States knew nothing about the raids. Despite McNamara’s nimble answers, North Vietnam’s insistence that there was a connection between 34A and the Desoto patrols was only natural.

Despite Morse’s doubts, Senate reaction fell in behind the Johnson team, and the question of secret operations was overtaken by the issue of punishing Hanoi for its blatant attack on a U.S. warship in international waters. On 7 August, the Senate passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, allowing the administration greater latitude in expanding the war by a vote of 88 to 2. Senator Morse was one of the dissenters. The House passed the resolution unanimously.17

America’s Vietnam War had begun in earnest. Within the year, U.S. bombers would strike North Vietnam, and U.S. ground units would land on South Vietnamese soil. But for a band of South Vietnamese commandos and a handful of U.S. advisers, not much had changed. The publicity caused by the Tonkin Gulf incident and the subsequent resolution shifted attention away from covert activities and ended high-level debate over the wisdom of secret operations against North Vietnam. In the future, conventional operations would receive all the attention. This was the only time covert operations against the North came close to being discussed in public. For the rest of the war they would be truly secret—and in the end they were a dismal failure.

1. Message, COMUSMACV 291233Z July 1964, CP 291345Z July 1964.

2. By late July 1964, SOG had four Nasty-class patrol boats, designated PTF-3, PTF-4, PTF-5, PTF-6 (PTF—fast patrol boat). PTF-1 and PTF-2 were U.S.-built 1950s vintage boats pulled out of mothballs and sent to Vietnam. They were nicknamed "gassers" because they burned gasoline rather than diesel fuel.

3. A brief account of the raids is in MACVSOG 1964 Command History, Annex A, 14 January 1965, pp. IV-2 to IV-4.

4. CIA Bulletin, 3 August 1964 (see Edward J. Marolda and Oscar P. Fitzgerald, The United States Navy and the Vietnam Conflict: From Military Assistance to Combat, 1959-1965 [Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1986], p. 422).

5. Quoted in Steve Edwards, "Stalking the Enemy’s Coast," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (February 1992), p. 59.

6. Marolda and Fitzgerald, p. 402.

7. Ibid., pp. 400-404; Edwards, p. 59.

8. JCS, "34A Chronology of Events," (see Marolda and Fitzgerald, p. 424); Porter, Vietnam: The Definitive Documentation (Stanfordville, NY: 1979), vol. 2, pp. 313-314.

9. George C. Herring, ed., The Secret Diplomacy of the Vietnam War: The Negotiating Volumes of the Pentagon Papers (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1983), p. 18.

10. Summary Notes of the 538th Meeting of the NSC, 4 August 1964, 6:15-6:40 p.m., Foreign Relations of the United States 1964-1968, vol. 1, Vietnam 1964 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1992), p. 611. Hereafter referred to as FRUS, Vietnam 1964; Congressional Research Service, The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships, Part II, 1961-1964 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1984), p. 287; Message CTG72.1 040140Z August 1964 (Marolda and Fitzgerald, p. 425).

11. Joseph C. Goulden, Truth Is the First Casualty: The Gulf of Tonkin Affair—Illusion and Reality (Chicago: Rand McNally & Co., 1969), p. 80. For the Navy’s official account stating that both incidents occurred and that 34A and Desoto were "entirely distinct," see Marolda and Fitzgerald, pp. 426-436.

12. Interview, authors with James Hawes, 31 March 1996.

13. Telegram from Embassy in Vietnam to Department of State, 7 August 1964, FRUS 1964, vol. 1, p. 646.

14. Telegram from the Department of State to the Embassy in Vietnam, 3 August 1964, FRUS, Vietnam, 1964, p. 603.

15. Robert S. McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (New York: Times Books, 1995), pp. 136-137.

16. Ibid.

17. William Conrad Gibbons, The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War, Part II, 1961-1964, pp. 302-303.